14.5: Mannerism

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 264024

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Mannerism

Mannerist artists began to reject the harmony and ideal proportions of the Renaissance in favor of irrational settings, artificial colors, unclear subject matters, and elongated forms.

Learning Objectives

Describe the Mannerist style, how it differs from the Renaissance, and reasons why it emerged.

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Mannerism came after the High Renaissance and before the Baroque .

- The artists who came a generation after Raphael and Michelangelo had a dilemma. They could not surpass the great works that had already been created by Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo. This is when we start to see Mannerism emerge.

- Jacopo da Pontormo (1494–1557) represents the shift from the Renaissance to the Mannerist style .

Key Terms

- Mannerism: Style of art in Europe from c. 1520–1600. Mannerism came after the High Renaissance and before the Baroque. Not every artist painting during this period is considered a Mannerist artist.

Mannerism is the name given to a style of art in Europe from c. 1520–1600. Mannerism came after the High Renaissance and before the Baroque. Not every artist painting during this period is considered a Mannerist artist, however, and there is much debate among scholars over whether Mannerism should be considered a separate movement from the High Renaissance, or a stylistic phase of the High Renaissance. Mannerism will be treated as a separate art movement here as there are many differences between the High Renaissance and the Mannerist styles.

Style

What makes a work of art Mannerist? First we must understand the ideals and goals of the Renaissance. During the Renaissance artists were engaging with classical antiquity in a new way. In addition, they developed theories on perspective , and in all ways strived to create works of art that were perfect, harmonious, and showed ideal depictions of the natural world. Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo are considered the artists who reached the greatest achievements in art during the Renaissance.

The Renaissance stressed harmony and beauty and no one could create more beautiful works than the great three artists listed above. The artists who came a generation after had a dilemma; they could not surpass the great works that had already been created by da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo. This is when we start to see Mannerism emerge. Younger artists trying to do something new and different began to reject harmony and ideal proportions in favor of irrational settings, artificial colors, unclear subject matters, and elongated forms .

Jacopo da Pontormo

Jacopo da Pontormo (1494–1557) represents the shift from the Renaissance to the Mannerist style. Take for example his Deposition from the Cross, an altarpiece that was painted for a chapel in the Church of Santa Felicita, Florence. The figures of Mary and Jesus appear to be a direct reference to Michelangelo’s Pieta. Although the work is called a “Deposition,” there is no cross. Scholars also refer to this work as the “Entombment” but there is no tomb. This lack of clarity on subject matter is a hallmark of Mannerist painting. In addition, the setting is irrational, almost as if it is not in this world, and the colors are far from naturalistic. This work could not have been produced by a Renaissance artist. The Mannerist movement stresses different goals and this work of art by Pontormo demonstrates this new, and different style.

Mannerist Painting

Mannerism emerged from the later years of the Italian High Renaissance, and is notable for its sophisticated and artificial qualities.

Learning Objectives

Contrast the painting of High Mannerism with its earlier, anti-classical phase

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Mannerist painting encompasses a variety of approaches influenced by, and reacting to, the harmonious ideals and restrained naturalism associated with High Renaissance artists. Mannerism is notable for its intellectual sophistication as well as its artificial (as opposed to naturalistic) qualities.

- Mannerism developed in both Florence and Rome , from around 1520 until about 1580. The early Mannerist painters are notable for elongated forms , precariously balanced poses, a collapsed perspective , irrational settings, and theatrical lighting.

- The second period of Mannerist painting, called “Maniera Greca,” is differentiated from the earlier “anti-classical” phase. High Mannerists stressed intellectual conceits and artistic virtuosity, features that have led later critics to accuse them of working in an unnatural and affected “manner.”

Key Terms

- Sack of Rome: A military event carried out on May 6, 1527 by the mutinous troops of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor in Rome.

- Mannerism: A style of art developed at the end of the High Renaissance, characterized by the deliberate distortion and exaggeration of perspective, especially the elongation of figures.

Mannerism

Mannerism is a period of European art that emerged from the later years of the Italian High Renaissance. It began around 1520 and lasted until about 1580 in Italy, when a more Baroque style began to be favored. Stylistically, Mannerist painting encompasses a variety of approaches influenced by, and reacting to, the harmonious ideals and restrained naturalism associated with artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and early Michelangelo. Mannerism is notable for its intellectual sophistication as well as its artificial (as opposed to naturalistic) qualities. There is an existing debate between scholars as to whether Mannerism was its own, independent art movement, or if it should be considered as part of the High Renaissance.

Mannerist Painting

Mannerism developed in both Florence and Rome. The early Mannerist painters in Florence—especially Jacopo da Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino, both students of Andrea del Sarto—are notable for using elongated forms, precariously balanced poses, a collapsed perspective, irrational settings, and theatrical lighting. Parmigianino (a student of Correggio) and Giulio Romano (Raphael’s head assistant) were moving in similarly stylized aesthetic directions in Rome. These artists had matured under the influence of the High Renaissance, and their style has been characterized as a reaction or exaggerated extension of it.

In other words, instead of studying nature directly, younger artists began studying Hellenistic sculptures and paintings of masters past. Therefore, this style is often identified as “anti-classical,” yet at the time it was considered a natural progression from the High Renaissance. The earliest experimental phase of Mannerism, known for its “anti-classical” forms, lasted until about 1540 or 1550. This period has been described as both a natural extension of the art of Andrea del Sarto, Michelangelo, and Raphael, as well as a decline of those same artists’ classicizing achievements.

In past analyses, it has been noted that Mannerism arose in the early 16th century alongside a number of other social, scientific, religious and political movements such as the Copernican model, the Sack of Rome , and the Protestant Reformation ‘s increasing challenge to the power of the Catholic Church. Because of this, the style’s elongated forms and distorted forms were once interpreted as a reaction to the idealized compositions prevalent in High Renaissance art.

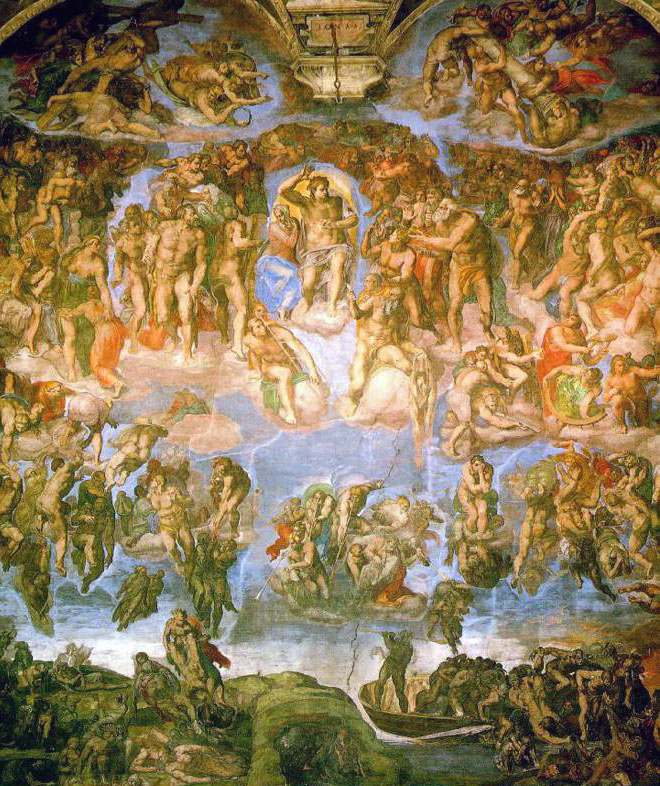

This explanation for the radical stylistic shift in 1520 has fallen out of scholarly favor, though the early Mannerists are still set in stark contrast to High Renaissance conventions; the immediacy and balance achieved by Raphael’s School of Athens no longer seemed interesting to young artists. Indeed, Michelangelo himself displayed tendencies towards Mannerism, notably in his vestibule to the Laurentian Library, in the figures on his Medici tombs, and above all the Sistine Chapel .

Maniera Greca

The second period of Mannerist painting, called “Maniera Greca,” or High Mannerism, is commonly differentiated from the earlier, so-called “anti-classical” phase. Influenced by earlier Byzantine art, High Mannerists stressed intellectual conceits and artistic virtuosity, features that have led later critics to accuse them of working in an unnatural and affected “manner” (maniera). Maniera artists held their elder contemporary Michelangelo as their prime example; theirs was an art imitating art, rather than an art imitating nature. Maniera art combines exaggerated elegance with exquisite attention to surface and detail: porcelain-skinned figures recline in an even, tempered light, regarding the viewer with a cool glance, if at all. The Maniera subject rarely displays an excess of emotion, and for this reason is often interpreted as “cold” or “aloof. ”

A number of the earliest Mannerist artists who had been working in Rome during the 1520s fled the city after the Sack of Rome in 1527. As they spread out across the continent in search of employment, their style was distributed throughout Italy and Europe. The result was the first international artistic style since the Gothic style (including French, English, and Dutch Mannerism styles). The style waned in Italy after 1580, as a new generation of artists, including the Carracci brothers, Caravaggio and Cigoli, reemphasized naturalism. Walter Friedlaender identified this period as “anti-mannerism,” just as the early Mannerists were “anti-classical” in their reaction to the High Renaissance.

Mannerist Sculpture

Mannerist sculpture, like Mannerist painting, was characterized by elongated forms, spiral angles, twisting poses, and aloof subject gazes.

Learning Objectives

Define characteristics of Mannerist sculpture

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Figura serpentinata (Italian: serpentine figure) is a style in painting and sculpture that is typical of Mannerism . It is similar, but not identical, to contrapposto , and often features figures in spiral poses.

- The Mannerist style of sculpture began to create a form in which figures showed physical power, passion, tension, and semantic perfection. Movements were not without motivation, nor even simply done with a will, but were shown in a pure form.

- Mannerist sculpture was an attempt to find an original style that would surpass the achievements of the High Renaissance , which was equated with Michelangelo. Much of the struggle to surpass his success centered on commissions to fill other places in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence, next to Michelangelo’s David.

Key Terms

- Figura Serpentinata: Figura Serpentinata (Italian: serpentine figure) is a style in painting and sculpture that is typical of Mannerism. It is similar, but not identical, to contrapposto, and features figures often in a spiral pose.

- Mannerism: A style of art developed at the end of the High Renaissance, characterized by the deliberate distortion and exaggeration of perspective, especially the elongation of figures.

- piazza: A public square, especially in an Italian city.

While sculpture of the High Renaissance is characterized by forms with perfect proportions and restrained beauty, as best characterized by Michelangelo’s David, Mannerist sculpture, like Mannerist painting, was characterized by elongated forms, spiral angels, twisted poses, and aloof subject gazes. Additionally, Mannerist sculptors worked in precious metals much more frequently than sculptors of the High Renaissance.

Figura serpentinata (Italian: serpentine figure) is a style in painting and sculpture that is typical of Mannerism. It is similar, but not identical, to contrapposto, and often features figures in spiral poses. Early examples can be seen in the work of Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo. In defining figura serpentinata, Emil Maurer writes of the painter and theorist Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo: “the recommended ideal form unites, after Lomazzo, three qualities: the pyramid , the ‘serpentinata’ movement and a certain numerical proportion, all three united to form one whole. At the same time, precedence is given to the ‘moto’, that is, to the meandering movement, which should make the pyramid, in exact proportion, into the geometrical form of a cone.”

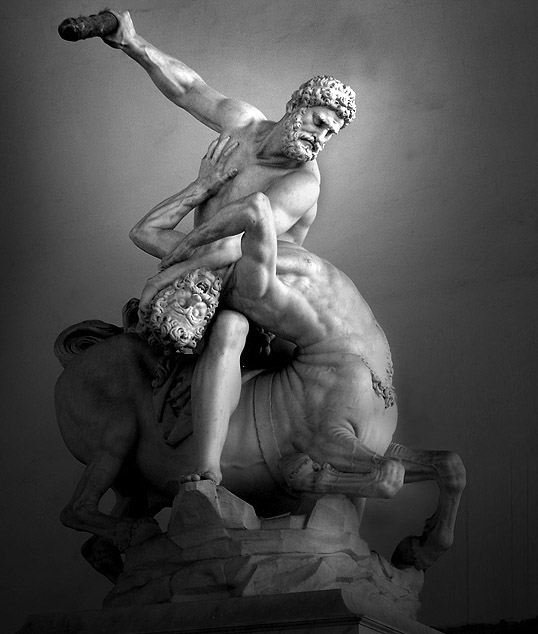

With the loosening of the norms of the High Renaissance and the development of the “Serpentinata” style, the Mannerist style’s structures and rules began to be systematized. The Mannerist style of sculpture began to create a form in which figures showed physical power, passion, tension, and semantic perfection. Mannerist figural sculpture was marked by contorted, twisting poses, as best evidenced by Giambologna’s Rape of the Sabine Women.

As in painting, early Italian Mannerist sculpture was largely an attempt to find an original style that would expand and surpass the achievements of the High Renaissance. For contemporaries in sculpture, the High Renaissance was equated with Michelangelo, and much of the struggle to surpass his success was played out in commissions to fill other places in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence, next to Michelangelo’s David.

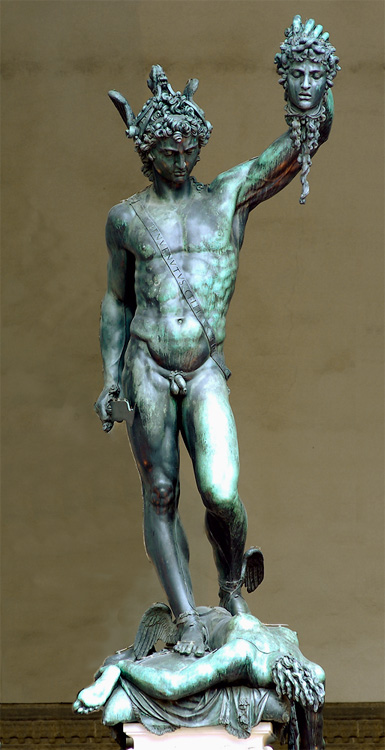

For example, Baccio Bandinelli took over the project of Herculesand Cacus from Michelangelo, although his work was maliciously compared by Benvenuto Cellini to “a sack of melons.” Like other works of Mannerists, Bandinelli removes far more of the original block of stone than Michelangelo would have done. Outside of natural stone sculptures, Cellini’s bronze Perseus with the head of Medusa is a Mannerist masterpiece, designed with eight angles of view.

Small bronze figures for collector’s cabinets, often mythological subjects with nudes, were characteristic of Mannerist sculpture. They were a popular Renaissance form at which Giambologna excelled in the later part of the century. He and his followers devised elegant, elongated examples of the figura serpentinata, often of two intertwined figures, that were interesting from all angles and joined the Piazza della Signora collection.

Mannerist Architecture

During the Mannerist period, architects experimented with using architectural forms to emphasize solid and spatial relationships.

They did so by deliberately playing with the symmetry, order, and harmony typically found in Renaissance architecture.

Learning Objectives

Relate Mannerist architecture to the Early Renaissance style that came before

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Stylistically, Mannerist architecture was marked by widely diverging tendencies from Renaissance and Medieval styles that eventually led to the Baroque style, in which the same architectural vocabulary was used for very different rhetoric.

- Michelangelo (1475–1564) is the best known artist associated with Mannerism .

Key Terms

- Mannerist architecture: During the Mannerist period, architects experimented with using architectural forms to emphasize solid and spatial relationships. The Renaissance ideal of harmony gave way to freer and more imaginative rhythms.

During the High Renaissance , architectural concepts derived from classical antiquity were developed and used with greater surety. The most representative architect of this period is Bramante (1444–1514), who expanded the applicability of classical architecture to contemporary buildings in a style that would dominate Italian architecture in the 16th century. Hallmarks of High Renaissance architecture are symmetry , proportion, order, harmony, and deliberate references to the buildings of the classical past.

During the Mannerist period architects experimented with using architectural forms to emphasize solid and spatial relationships. They did so by deliberately playing with the symmetry, order, and harmony typically found in Renaissance architecture. As a result, Mannerist architecture appears playful, almost as if the architects are deliberately playing with expectations put forth by Renaissance architecture.

In Mannerist architecture, the Renaissance ideal of harmony gave way to freer and more imaginative rhythms. The best known artist associated with the Mannerist style is Michelangelo (1475–1564). With his design for the vestibule of the Laurentian Library, there are ambiguities of how to read the space , which result from Michelangelo’s playfulness with the architecture itself. Columns lean back instead of forward, and the corners come out toward you instead of recessing. Michelangelo was aware of the ideals of Renaissance architecture but he is deliberately playing with those ideals and creating something new.

Stylistically, Mannerist architecture was marked by widely diverging tendencies from Renaissance and Medieval styles that eventually led to the Baroque style, in which the same architectural vocabulary was used for very different rhetoric.

Baldassare Peruzzi (1481–1536) was an architect working in Rome whose work bridged the High Renaissance and Mannerism. His Villa Farnesina of 1509 is a very regular monumental cube of two equal stories, with the bays articulated by orders of pilasters .

Villa Farnesina, Rome, by Peruzzi, 1506–1510.

Peruzzi’s most famous work is the Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne in Rome. The unusual features of this building are that its façade curves gently to follow a curving street. It has, in its ground floor, a dark central portico running parallel to the street, but as a semi-enclosed space, rather than an open loggia . Above this, three undifferentiated floors rise, the upper two with identical small horizontal windows in thin flat frames that contrast strangely with the deep porch, which has served, from the time of its construction, as a refuge to the city’s poor. All of these architectural features are unexpected and disrupt the ideas of harmonious proportions, making it a Mannerist building.

Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne, Rome, by Peruzzi

Giulio Romano (1499–1546) was a pupil of Raphael, assisting him on various works for the Vatican. Romano was also a highly inventive designer, working for Federico II Gonzaga at Mantua on the Palazzo del Te (1524–1534), a project that combined his skills as architect, sculptor, and painter. In this work, which incorporated garden grottoes and extensive frescoes , he uses illusionistic effects, surprising combinations of architectural form and texture , and features that seem somewhat disproportionate or out of alignment, making it very much a Mannerist structure.

Mannerism and the Counter-Reformation

Mannerism concerned many Catholic leaders in the wake of the Reformation, as they were seen as lacking pious appeal.

Learning Objectives

Distinguish the artistic ideal of the Counter-Reformation from Mannerism and the art of the Reformation in Northern Europe

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Pressure to restrain religious imagery affected art from the 1530s and influenced several decrees from the final session of the Council of Trent in 1563. These decrees included short passages on religious images that had significant impact on the development of Catholic art during the Counter- Reformation .

- The Counter-Reformation Catholic Church promoted art with “sacred” or religious content. In other words, art was to be strictly religious, created for the purpose of glorifying God and Catholic traditions.

Key Terms

- refectory: A dining-hall especially in an institution such as a college or monastery.

- Counter-Reformation: The period of Catholic revival beginning with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) and ending at the close of the Thirty Years’ War (1648); sometimes considered a response to the Protestant Reformation.

Italian Painting and Mannerism

Italian Renaissance painting after 1520 developed certain characteristics that are considered Mannerist , such as elongated forms and irrational settings. Mannerism, as well as works from the High Renaissance , concerned many Catholic leaders in the wake of the Reformation, as they were seen as lacking pious appeal. Furthermore, a great divergence had arisen between the Catholic Church and Protestant reformers of Northern Europe regarding the content and style of art work.

Church pressure to restrain religious imagery affected art from the 1530s and influenced several decrees from the final session of the Council of Trent in 1563. These decrees included short passages concerning religious images that had significant impact on the development of Catholic art during the Counter-Reformation. The Church felt that religious art in Catholic countries (especially Italy) had lost its focus on religious subject matter. It focused on decorative qualities instead, with heavy influences from classical , pagan art, leading to a church decree that “art was to be direct and compelling in its narrative presentation, that it was to provide an accurate presentation of the biblical narrative or saint’s life, rather than adding incidental and imaginary moments, and that it was to encourage piety” (Paoletti and Radke, Art in Renaissance Italy). The reforms that resulted from this council are what set the basis for Counter-Reformation art.

The Counter-Reformation Movement

While the Protestants largely removed public art from religion and moved towards a more “secular” style of art, embracing the concept of glorifying God through depictions of nature, the Counter-Reformation Catholic Church promoted art with “sacred” or religious content. In other words, art was to be strictly religious, created for the purpose of glorifying God and Catholic traditions.

To that end, The Last Judgment, a fresco on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo (1534–41), came under attack for its classical imagery and the large quantity of nudes, some of which were interpreted at the time as being in compromising poses. The Last Judgment was an object of dispute between critics within the Catholic Counter-Reformation and those who appreciated the genius of the artist and the Mannerist style of the painting. Michelangelo was accused of being insensitive to proper decorum, and of flaunting personal style over appropriate depictions of content. The fresco was also completed at a time when prints could be made of the work and distributed throughout Northern Europe, the base for criticisms against the Catholic Church. While Michelangelo had been celebrated during the Renaissance for his classical influence and depictions of monumental nudes in a variety of poses, here he was being criticized for The Last Judgment. Michelango was not doing anything new or different from his previous style, which had been celebrated in the past. This demonstrates how the historical situation had altered and just how threatened the Catholic Church felt at this time in history.

Scipione Pulzone’s painting of the Lamentation, commissioned for the Gesu Church in 1589, gives a clear demonstration of what the Council of Trent was striving for in the new style of religious art. With the focus of the painting giving direct attention to the crucifixion of Christ, it complies with the religious content of the council and shows the story of the Passion while keeping Christ in the image of the ideal human.

On the other hand, in Paolo Veronese’s painting The Last Supper (subsequently renamed The Feast in the House of Levi), one can see what the Council regarded as inappropriate. Veronese was summoned before the Inquisition on the basis that his composition was indecorous for the refectory of a monastery. The painting shows a fantasy version of a Venetian patrician feast, with, in the words of the Inquisition: “buffoons, drunken Germans, dwarfs and other such scurrilities” as well as extravagant costumes and settings. Veronese was told that he must change his painting within a three-month period; instead he simply changed the title to The Feast in the House of Levi .

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Deposition_from_the_Cross__artble.com. Provided by: artble. Located at: http://www.artble.com/artists/rosso_fiorentino/paintings/deposition_from_the_cross. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Pontormo. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Pontormo. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Deposition from the Cross (Pontormo). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Deposition_from_the_Cross_(Pontormo). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mannerism. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Mannerism. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Pontormo. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Pontormo. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mannerism. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Mannerism. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

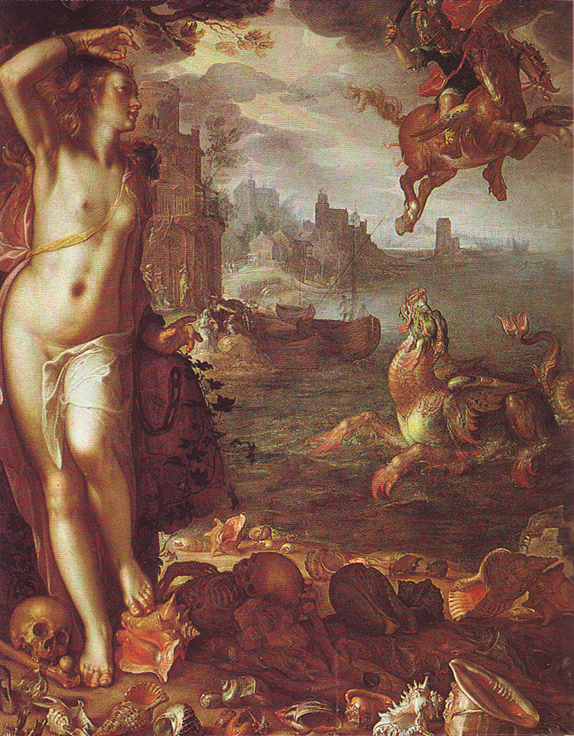

- Louvre wtewael 1616. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Louvre_wtewael_1616.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Parmigianino 003b. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Parmigianino_003b.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Jacopo_Pontormo_004.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Mannerism. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Michelangelo the libyan. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Michelangelo_the_libyan.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Madonna with the Long Neck. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Madonna_with_the_Long_Neck. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mannerism. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Mannerism. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mannerism. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Mannerism. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Boundless. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: www.boundless.com//art-history/definition/sack-of-rome. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Giambologna herculesenesso. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Giambologna_herculesenesso.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Persee-florence. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Persee-florence.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Giambologna raptodasabina. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Giambologna_raptodasabina.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Perseus with the Head of Medusa. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Perseus_with_the_Head_of_Medusa. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Rape of the Sabine Women. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Rape_of_the_Sabine_Women. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Figura serpentinata. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Figura_serpentinata. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mannerism. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Mannerism%23Sculpture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mannerism. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Mannerism. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Figura Serpentinata. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Figura%20Serpentinata. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- piazza. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/piazza. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Palazzo Te Mantova 1. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Palazzo_Te_Mantova_1.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Biblioteca_laurenziana2C_vestibolo_04.JPG. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Mannerism#Mannerist_architecture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Villa_farnesina_01.JPG. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Villa_Farnesina. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Palazzo_Massimo_alle_Colonne.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Mannerism. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Palazzo del Te. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Palazzo_del_Te. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Renaissance architecture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Renaissance_architecture%23Mannerism. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Renaissance architecture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Renaissance_architecture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Mannerist architecture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Mannerist%20architecture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Michelangelo - Fresco of the Last Judgement. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Michelangelo_-_Fresco_of_the_Last_Judgement.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Lamentation Scipione Pulzone. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Lamentation_Scipione_Pulzone.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Paolo Veronese. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Paolo_Veronese.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- The Last Judgment (Michelangelo). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Last_Judgment_(Michelangelo). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Counter-Reformation. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Counter-Reformation%23Decrees_on_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- The Reformation and art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Reformation_and_art%23Art_and_the_Counter-Reformation. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- refectory. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/refectory. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Counter-Reformation. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Counter-Reformation. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike