8.3: The Roman Republic

- Page ID

- 46121

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Establishment of the Roman Republic

After the publicoutcry that arose as a result of the rape of Lucretia, Romans overthrew the unpopular king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, and established a republican form of government.

Learning Objectives

Explain why and how Rome transitioned from a monarchy to a republic

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Roman monarchy was overthrown around 509 BCE, during a political revolution that resulted in the expulsion of Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the last king of Rome.

- Despite waging a number of successful campaigns against Rome’s neighbors, securing Rome’s position as head of the Latin cities, and engaging in a series of public works, Tarquinius was a very unpopular king, due to his violence and abuses of power.

- When word spread that Tarquinius’s son raped Lucretia, the wife of the governor of Collatia, an uprising occurred in which a number of prominent patricians argued for a change in government.

- A general election was held during a legal assembly, and participants voted in favor of the establishment of a Roman republic.

- Subsequently, all Tarquins were exiled from Rome and an interrex and two consuls were established to lead the new republic.

Key Terms

- patricians: A group of ruling class families in ancient Rome.

- plebeians: A general body of free Roman citizens who were part of the lower strata of society.

- interrex: Literally, this translates to mean a ruler that presides over the period between the rule of two separate kings; or, in other words, a short-term regent.

The Roman monarchy was overthrown around 509 BCE, during a political revolution that resulted in the expulsion of Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the last king of Rome. Subsequently, the Roman Republic was established.

Background

Tarquinius was the son of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, the fifth king of Rome’s Seven Kings period. Tarquinius was married to Tullia Minor, the daughter of Servius Tullius, the sixth king of Rome’s Seven Kings period. Around 535 BCE, Tarquinius and his wife, Tullia Minor, arranged for the murder of his father-in-law. Tarquinius became king following Servius Tullius’s death.

Tarquinius waged a number of successful campaigns against Rome’s neighbors, including the Volsci, Gabii, and the Rutuli. He also secured Rome’s position as head of the Latin cities, and in a series of public works, such as the completion of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. However, Tarquinius remained an unpopular king for a number of reasons. He refused to bury his predecessor and executed a number of leading senators whom he suspected remained loyal to Servius. Following these actions, he refused to replace the senators he executed and refused to consult the Senate in matters of government going forward, thus diminishing the size and influence of the Senate greatly. He also went on to judge capital criminal cases without the advice of his counselors, stoking fear among his political opponents that they would be unfairly targeted.

The Rape of Lucretia and An Uprising

Tarquin and Lucretia

During Tarquinius’s war with the Rutuli, his son, Sextus Tarquinius, was sent on a military errand to Collatia, where he was received with great hospitality at the governor’s mansion. The governor’s wife, Lucretia, hosted Sextus while the governor was away at war. During the night, Sextus entered her bedroom and raped her. The next day, Lucretia traveled to her father, Spurius Lucretius, a distinguished prefect in Rome, and, before witnesses, informed him of what had happened. Because her father was a chief magistrate of Rome, her pleas for justice and vengeance could not be ignored. At the end of her pleas, she stabbed herself in the heart with a dagger, ultimately dying in her own father’s arms. The scene struck those who had witnessed it with such horror that they collectively vowed to publicly defend their liberty against the outrages of such tyrants.

Lucius Junius Brutus, a leading citizen and the grandson of Rome’s fifth king, Tarquinius Priscus, publicly opened a debate on the form of government that Rome should have in place of the existing monarchy. A number of patricians attended the debate, in which Brutus

proposed the banishment of the Tarquins from all territories of Rome, and the appointment of an interrex to nominate new magistrates and to oversee an election of ratification. It was decided that a republican form of government should temporarily replace the monarchy, with two consuls replacing the king and executing the will of a patrician senate. Spurius Lucretius was elected interrex, and he proposed Brutus, and Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, a leading citizen who was also related to Tarquinius Priscus, as the first two consuls. His choice was ratified by the comitia curiata, an organization of patrician families who primarily ratified decrees of the king.

In order to rally the plebeians to their cause, all were summoned to a legal assembly in the forum, and Lucretia’s body was paraded through the streets. Brutus gave a speech and a general election was held. The results were in favor of a republic. Brutus left Lucretius in command of the city as interrex, and pursued the king in Ardea where he had been positioned with his army on campaign. Tarquinius, however, who had heard of developments in Rome, fled the camp before Brutus arrived, and the army received Brutus favorably, expelling the king’s sons from their encampment. Tarquinius was subsequently refused entry into Rome and lived as an exile with his family.

The Establishment of the Republic

Although there is no scholarly agreement as to whether or not it actually took place, Plutarch and Appian both claim that Brutus’s first act as consul was to initiate an oath for the people, swearing never again to allow a king to rule Rome. What is known for certain is that he replenished the Senate to its original number of 300 senators, recruiting men from among the equestrian class. The new consuls also created a separate office, called the rex sacrorum, to carry out and oversee religious duties, a task that had previously fallen to the king.

The two consuls continued to be elected annually by Roman citizens and advised by the senate. Both consuls were elected for one-year terms and could veto each other’s actions. Initially, they were endowed with all the powers of kings past, though over time these were broken down further by the addition of magistrates to the governmental system. The first magistrate added was the praetor, an office that assumed judicial authority from the consuls. After the praetor, the censor was established, who assumed the power to conduct the Roman census.

Structure of the Republic

The Roman Republic was composed of the Senate, a number of legislative assemblies, and elected magistrates.

Learning Objectives

Describe the political structure of the Roman Republic

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Constitution of the Roman Republic was a set of guidelines and principles passed down, mainly through precedent. The constitution was largely unwritten and uncodified, and evolved over time.

- Roman citizenship was a vital prerequisite to possessing many important legal rights. The Senate passed decrees that were called senatus consulta, ostensibly “advice” from the senate to a magistrate. The focus of the Roman Senate was usually foreign policy.

- There were two types of legislative assemblies. The first was the comitia (“committees”), which were assemblies of all Roman citizens. The second was the concilia (“councils”), which were assemblies of specific groups of citizens.

- The comitia centuriata was the assembly of the centuries (soldiers), and they elected magistrates who had imperium powers (consuls and praetors). The comitia tributa, or assembly of the tribes (the citizens of Rome ), was presided over by a consul and composed of 35 tribes. They elected quaestors, curule aediles, and military tribunes.

- Dictators were sometimes elected during times of military emergency, during which the constitutional government would be disbanded.

Key Terms

- patricians: A group of ruling class families in ancient Rome.

- plebeian: A general body of free Roman citizens who were part of the lower strata of society.

- Roman Senate: A political institution in the ancient Roman Republic. It was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors.

The Constitution of the Roman Republic was a set of guidelines and principles passed down, mainly through precedent. The constitution was largely unwritten and uncodified, and evolved over time. Rather than creating a government that was primarily a democracy (as was ancient Athens), an aristocracy (as was ancient Sparta), or a monarchy (as was Rome before, and in many respects after, the Republic), the Roman constitution mixed these three elements of governance into their overall political system. The democratic element took the form of legislative assemblies; the aristocratic element took the form of the Senate; and the monarchical element took the form of the many term-limited consuls.

The Roman Senate

The Senate’s ultimate authority derived from the esteem and prestige of the senators, and was based on both precedent and custom. The Senate passed decrees, which were called senatus consulta, ostensibly “advice” handed down from the senate to a magistrate. In practice, the magistrates usually followed the senatus consulta. The focus of the Roman Senate was usually foreign policy. However, the power of the Senate expanded over time as the power of the legislative assemblies declined, and eventually the Senate took a greater role in civil law-making. Senators were usually appointed by Roman censors, but during times of military emergency, such as the civil wars of the 1st century BCE, this practice became less prevalent, and the Roman dictator, triumvir, or the Senate itself would select its members.

Legislative Assemblies

Roman citizenship was a vital prerequisite to possessing many important legal rights, such as the rights to trial and appeal, marriage, suffrage, to hold office, to enter binding contracts, and to enjoy special tax exemptions. An adult male citizen with full legal and political rights was called optimo jure. The optimo jure elected assemblies, and the assemblies elected magistrates, enacted legislation, presided over trials in capital cases, declared war and peace, and forged or dissolved treaties. There were two types of legislative assemblies. The first was the comitia (“committees”), which were assemblies of all optimo jure. The second was the concilia (“councils”), which were assemblies of specific groups of optimo jure.

Citizens on these assemblies were organized further on the basis of curiae (familial groupings), centuries (for military purposes), and tribes (for civil purposes), and each would each gather into their own assemblies. The Curiate Assembly served only a symbolic purpose in the late Republic, though

the assembly was used to ratify the powers of newly elected magistrates by passing laws known as leges curiatae. The comitia centuriata was the assembly of the centuries (soldiers). The president of the comitia centuriata was usually a consul, and the comitia centuriata would elect magistrates who had imperium powers (consuls and praetors). It also elected censors. Only the comitia centuriata could declare war and ratify the results of a census. It also served as the highest court of appeal in certain judicial cases.

The assembly of the tribes, the comitia tributa, was presided over by a consul, and was composed of 35 tribes. The tribes were not ethnic or kinship groups, but rather geographical subdivisions. While it did not pass many laws, the comitia tributa did elect quaestors, curule aediles, and military tribunes. The Plebeian Council was identical to the assembly of the tribes, but excluded the patricians. They elected their own officers, plebeian tribunes, and plebeian aediles. Usually a plebeian tribune would preside over the assembly. This assembly passed most laws, and could also act as a court of appeal.

Since the tribunes were considered to be the embodiment of the plebeians, they were sacrosanct. Their sacrosanctness was enforced by a pledge, taken by the plebeians, to kill any person who harmed or interfered with a tribune during his term of office. As such, it was considered a capital offense to harm a tribune, to disregard his veto, or to interfere with his actions. In times of military emergency, a dictator would be appointed for a term of six months. The constitutional government would be dissolved, and the dictator would be the absolute master of the state. When the dictator’s term ended, constitutional government would be restored.

Executive Magistrates

Magistrates were the elected officials of the Roman republic. Each magistrate was vested with a degree of power, and the dictator, when there was one, had the highest level of power. Below the dictator was the censor (when they existed), and the consuls, the highest ranking ordinary magistrates. Two were elected every year and wielded supreme power in both civil and military powers. The ranking among both consuls flipped every month, with one outranking the other.

Below the consuls were the praetors, who administered civil law, presided over the courts, and commanded provincial armies. Censors conducted the Roman census, during which time they could appoint people to the Senate. Curule aediles were officers elected to conduct domestic affairs in Rome, who were vested with powers over the markets, public games, and shows. Finally, at the bottom of magistrate rankings were the quaestors, who usually assisted the consuls in Rome and the governors in the provinces with financial tasks. Plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles were considered representatives of the people, and acted as a popular check over the Senate through use of their veto powers, thus safeguarding the civil liberties of all Roman citizens.

Each magistrate could only veto an action that was taken by an equal or lower ranked magistrate. The most significant constitutional power a magistrate could hold was that of imperium or command, which was held only by consuls and praetors. This gave the magistrate in question the constitutional authority to issue commands, military or otherwise.

Election to a magisterial office resulted in automatic membership in the Senate for life, unless impeached. Once a magistrate’s annual term in office expired, he had to wait at least ten years before serving in that office again. Occasionally, however, a magistrate would have his command powers extended through prorogation, which effectively allowed him to retain the powers of his office as a promagistrate.

Roman Society Under the Republic

The bulk of Roman politics prior to the 1st century BCE focused on inequalities among the orders.

Learning Objectives

Describe the relationship between the government and the people in the time of the Roman Republic

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- A number of developments affected the relationship between Rome ’s republican government and

society, particularly in regard to how that relationship differed among patricians and plebeians. - In 494 BCE, plebeian soldiers refused to march against a wartime enemy, in order to demand the right to elect their own officials.

- The passage of Lex Trebonia forbade the co-opting of colleagues to fill vacant positions on tribunes in order to sway voting in favor of patrician blocs over plebeians.

- Throughout the 4th century BCE, a series of reforms were passed that required all laws passed by the plebeian council to have the full force of law over the entire population. This gave the plebeian tribunes a positive political impact over the entire population for the first time in Roman history.

- In 445 BCE, the plebeians demanded the right to stand for election as consul. Ultimately, a compromise was reached in which consular command authority was granted to a select number of military tribunes.

- The Licinio-Sextian law was passed in 367 BCE; it addressed the economic plight of the plebeians and prevented the election of further patrician magistrates.

- In the decades following the passage of the Licinio-Sextian law, further legislation was enacted that granted political equality to the plebeians. Nonetheless, it remained difficult for a plebeian from an unknown family to enter the Senate, due to the rise of a new patricio-plebeian aristocracy that was less interested in the plight of the average plebeian.

Key Terms

- patricians: A group of ruling class families in ancient Rome.

- plebeian: A general body of free Roman citizens who were part of the lower strata of society.

In the first few centuries of the Roman Republic, a number of developments affected the relationship between the government and the Roman people, particularly in regard to how that relationship differed across the separate strata of society.

The Patrician Era (509-367 BCE)

The last king of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, was overthrown in 509 BCE. One of the biggest changes that occurred as a result was the establishment of two chief magistrates, called consuls, who were elected by the citizens of Rome for an annual term. This stood in stark contrast to the previous system, in which a king was elected by senators, for life. Built in to the consul system were checks on authority, since each consul could provide balance to the decisions made by his colleague. Their limited terms of office also opened them up to the possibility of prosecution in the event of abuses of power. However, when consuls exercised their political powers in tandem, the magnitude and influence they wielded was hardly different from that of the old kings.

In 494 BCE, Rome was at war with two neighboring tribes, and plebeian soldiers refused to march against the enemy, instead seceding to the Aventine Hill. There, the plebeian soldiers took advantage of the situation to demand the right to elect their own officials. The patricians assented to their demands, and the plebeian soldiers returned to battle. The new offices that were created as a result came to be known as “plebeian tribunes,” and they were to be assisted by “plebeian aediles.”

In the early years of the republic, plebeians were not permitted to hold magisterial office. Tribunes and aediles were technically not magistrates, since they were only elected by fellow plebeians, as opposed to the unified population of plebeians and patricians. Although plebeian tribunes regularly attempted to block legislation they considered unfavorable, patricians could still override their veto with the support of one or more other tribunes. Tension over this imbalance of power led to the passage of Lex Trebonia, which forbade the co-opting of colleagues to fill vacant positions on tribunes in order to sway voting in favor of one or another bloc. Throughout the 4th century BCE, a series of reforms were passed that required all laws passed by the plebeian council to have equal force over the entire population, regardless of status as patrician or plebeian. This gave the plebeian tribunes a positive political impact over the entire population for the first time in Roman history.

In 445 BCE, the plebeians demanded the right to stand for election as consul. The Roman Senate initially refused them this right, but ultimately a compromise was reached in which consular command authority was granted to a select number of military tribunes, who, in turn, were elected by the centuriate assembly with veto power being retained by the senate.

Around 400 BCE, during a series of wars that were fought against neighboring tribes, the plebeians demanded concessions for the disenfranchisement they experienced as foot soldiers fighting for spoils of war that they were never to see. As a result, the Licinio-Sextian law was eventually passed in 367 BCE, which addressed the economic plight of the plebeians and prevented the election of further patrician magistrates.

The Conflict of the Orders Ends (367-287 BCE)

In the decades following the passage of the Licinio-Sextian law, further legislation was enacted that granted political equality to the plebeians. Nonetheless, it remained difficult for a plebeian from an unknown family to enter the Senate. In fact, the very presence of a long-standing nobility, and the Roman population’s deep respect for it, made it very difficult for individuals from unknown families to be elected to high office. Additionally, elections could be expensive, neither senators nor magistrates were paid for their services, and the Senate usually did not reimburse magistrates for expenses incurred during their official duties, providing many barriers to the entry of high political office by the non-affluent.

Ultimately, a new patricio-plebeian aristocracy emerged and replaced the old patrician nobility. Whereas the old patrician nobility existed simply on the basis of being able to run for office, the new aristocracy existed on the basis of affluence. Although a small number of plebeians had achieved the same standing as the patrician families of the past, new plebeian aristocrats were less interested in the plight of the average plebeian than were the old patrician aristocrats. For a time, the plebeian plight was mitigated, due higher employment, income, and patriotism that was wrought by a series of wars in which Rome was engaged; these things eliminated the threat of plebeian unrest. But by 287 BCE, the economic conditions of the plebeians deteriorated as a result of widespread indebtedness, and the plebeians sought relief. Roman senators, most of whom were also creditors, refused to give in to the plebeians’ demands, resulting in the first plebeian secession to Janiculum Hill.

In order to end the plebeian secession, a dictator, Quintus Hortensius, was appointed. Hortensius, who was himself a plebeian, passed a law known as the “Hortensian Law.” This law ended the requirement that an auctoritas patrum be passed before a bill could be considered by either the plebeian council or the tribal assembly, thus removing the final patrician senatorial check on the plebeian council. The requirement was not changed, however, in the centuriate assembly. This provided a loophole through which the patrician senate could still deter plebeian legislative influence.

Art and Literature in the Roman Republic

Culture flourished during the Roman Republic with the emergence of great authors, such as Cicero and Lucretius, and with the development of Roman relief and portraiture sculpture.

Learning Objectives

Recognize the wide extent of art and literature created during the Roman Republic

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Roman literature was, from its very inception, influenced heavily by Greek authors. Some of the earliest works we possess are of historical epics that tell the early military history of Rome. However, authors diversified their genres as the Republic expanded.

- Cicero is one of the most famous Republican authors, and his letters provide detailed information about an important period in Roman history.

- Romans typically produced historical sculptures in relief, as opposed to Greek free-standing sculpture. Small sculptures were considered luxury items, while moulded relief decoration in pottery vessels and small figurines were produced in great quantities for a wider section of the population.

- The most well-known surviving examples of Roman painting consist of the wall paintings from Pompeii and Herculaneum that were preserved in the aftermath of the fatal eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE.

- Veristic portraiture is a hallmark of Roman art during the Republic, though its use began to diminish during the 1st century BCE as civil wars threatened the empire and individual strong men began amassing more power.

Key Terms

- Cicero: A Roman philosopher, politician, lawyer, orator, political theorist, consul, and constitutionalist.

- veristic portraiture: A hyper-realistic portrayal of the subject’s facial characteristics; a common style of portraiture in the early to mid-Republic.

Literature

Roman literature was, from its very inception, heavily influenced by Greek authors. Some of the earliest works we possess are historical epics telling the early military history of Rome, similar to the Greek epic narratives of Homer, Herodotus, and Thucydides. Virgil, though generally considered to be an Augustan poet, represents the pinnacle of Roman epic poetry. His Aeneid tells the story of the flight of Aeneas from Troy, and his settlement of the city that would become Rome. As the Republic expanded, authors began to produce poetry, comedy, history, and tragedy. Lucretius, in his De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things), attempted to explicate science in an epic poem. The genre of satire was also common in Rome, and satires were written by, among others, Juvenal and Persius.

The Age of Cicero

Cicero has traditionally been considered the master of Latin prose. The writing he produced from approximately 80 BCE until his death in 43 BCE, exceeds that of any Latin author whose work survives, in terms of quantity and variety of genre and subject matter. It also possesses unsurpassed stylistic excellence. Cicero’s many works can be divided into four groups: letters, rhetorical treatises, philosophical works, and orations. His letters provide detailed information about an important period in Roman history, and offers a vivid picture of public and private life among the Roman governing class. Cicero’s works on oratory are our most valuable Latin sources for ancient theories on education and rhetoric. His philosophical works were the basis of moral philosophy during the Middle Ages, and his speeches inspired many European political leaders, as well as the founders of the United States.

Art

Early Roman art was greatly influenced by the art of Greece and the neighboring Etruscans, who were also greatly influenced by Greek art via trade. As the Roman Republic conquered Greek territory, expanding its imperial domain throughout the Hellenistic world, official and patrician sculpture grew out of the Hellenistic style that many Romans encountered during their campaigns, making it difficult to distinguish truly Roman elements from elements of Greek style. This was especially true since much of what survives of Greek sculpture are actually copies made of Greek originals by Romans. By the 2nd century BCE, most sculptors working within Rome were Greek, many of whom were enslaved following military conquests, and whose names were rarely recorded with the work they created. Vast numbers of Greek statues were also imported to Rome as a result of conquest as well as trade.

Rather than create free-standing works depicting heroic exploits from history or mythology, as the Greeks had, the Romans produced historical works in relief. Small sculptures were considered luxury items and were frequently the object of client-patron relationships. The silver Warren Cup and glass Lycurgus cup are examples of the high quality works that were produced during this period. For a wider section of the population, moulded relief decoration in pottery vessels and small figurines were produced in great quantities, and were often of great quality.

In the 3rd century BCE, Greek art taken during wars became popular, and many Roman homes were decorated with landscapes by Greek artists.

Of the vast body of Roman painting that once existed, only a few examples survive to the modern-age. The most well-known surviving examples of Roman painting are the wall paintings from Pompeii and Herculaneum, that were preserved in the aftermath of the fatal eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. A large number of paintings also survived in the catacombs of Rome, dating from the 3rd century CE to 400, prior to the Christian age, demonstrating a continuation of the domestic decorative tradition for use in humble burial chambers.Wall painting was not considered high art in either Greece or Rome. Sculpture and panel painting, usually consisting of tempera or encaustic painting on wooden panels, were considered more prestigious art forms.

A large number of Fayum mummy portraits, bust portraits on wood added to the outside of mummies by the Romanized middle class, exist in Roman Egypt. Although these are in some ways distinctively local, they are also broadly representative of the Roman style of painted portraits.

Roman portraiture during the Republic is identified by its considerable realism, known as veristic portraiture. Verism refers to a hyper-realistic portrayal of the subject’s facial characteristics. The style originated from Hellenistic Greece; however, its use in Republican Rome and survival throughout much of the Republic is due to Roman values, customs, and political life. As with other forms of Roman art, Roman portraiture borrowed certain details from Greek art, but adapted these to their own needs. Veristic images often show their male subject with receding hairlines, deep winkles, and even with warts. While the face of the portrait was often shown with incredible detail and likeness, the body of the subject would be idealized, and did not seem to correspond to the age shown in the face.

Portrait sculpture during the period utilized youthful and classical proportions, evolving later into a mixture of realism and idealism. Advancements were also made in relief sculptures, often depicting Roman victories. The Romans, however, completely lacked a tradition of figurative vase-painting comparable to that of the ancient Greeks, which the Etruscans had also emulated.

The Late Republic

The use of veristic portraiture began to diminish during the Late Republic in the 1st century BCE. During this time, civil wars threatened the empire and individual men began to gain more power. The portraits of Pompey the Great and Julius Caesar, two political rivals who were also the most powerful generals in the Republic, began to change the style of portraits and their use. The portraits of Pompey the Great were neither fully idealized, nor were they created in the same veristic style of Republican senators. Pompey borrowed a specific parting and curl of his hair from Alexander the Great, linking Pompey visually to Alexander’s likeness, and triggering his audience to associate him with Alexander’s characteristics and qualities.

Republican Wars and Conquest

By the end of the mid-Republic, Rome had achieved military dominance on both the Italian peninsula and within the Mediterranean.

Learning Objectives

Describe the key results and effects of major Republican wars

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Early Roman Republican wars were wars of both expansion and defense, aimed at protecting Rome from neighboring cities and nations, and establishing its territory within the region.

- The Samnite Wars were fought against the Etruscans and effectively finished off all vestiges of Etruscan power by 282 BCE.

- By the middle of the 3rd century and the end of the Pyrrhic War, Rome had effectively dominated the Italian peninsula and won an international military reputation.

- Over the course of the three Punic Wars, Rome completely defeated Hannibal and razed Carthage to the ground, thereby acquiring all of Carthage’s North African and Spanish territories.

- After four Macedonian Wars, Rome had established its first permanent foothold in the Greek world, and divided the Macedonian Kingdom into four client republics.

Key Terms

- Punic Wars: A series of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage, from 264 BCE to 146 BCE, that resulted in the complete destruction of Carthage.

- Pyrrhus: Greek general and statesman of the Hellenistic era. Later he became king of Epirus (r. 306-302, 297-272 BCE) and Macedon (r. 288-284, 273-272 BCE). He was one of the strongest opponents of early Rome. Some of his battles, though successful, cost him heavy losses, from which the term “Pyrrhic victory” was coined.

Early Republic

Early Campaigns (458-396 BCE)

The first Roman Republican wars were wars of both expansion and defense, aimed at protecting Rome from neighboring cities and nations, as well as establishing its territory in the region. Initially, Rome’s immediate neighbors were either Latin towns and villages or tribal Sabines from the Apennine hills beyond. One by one, Rome defeated both the persistent Sabines and the nearby Etruscan and Latin cities. By the end of this period, Rome had effectively secured its position against all immediate threats.

Expansion into Italy and the Samnite Wars (343-282 BCE)

The First Samnite War, of 343 BCE-341 BCE, was a relatively short affair. The Romans beat the Samnites in two battles, but were forced to withdraw from the war before they could pursue the conflict further, due to the revolt of several of their Latin allies in the Latin War. The Second Samnite War, from 327 BCE-304 BCE, was much longer and more serious for both the Romans and Samnites, but by 304 BCE the Romans had effectively annexed the greater part of the Samnite territory and founded several colonies therein. Seven years after their defeat, with Roman dominance of the area seemingly assured, the Samnites rose again and defeated a Roman army in 298 BCE, to open the Third Samnite War. With this success in hand, they managed to bring together a coalition of several of Rome’s enemies, but by 282 BCE, Rome finished off the last vestiges of Etruscan power in the region.

Pyrrhic War (280-275 BCE)

By the beginning of the 3rd century BCE, Rome had established itself as a major power on the Italian Peninsula, but had not yet come into conflict with the dominant military powers in the Mediterranean Basin at the time: the Carthage and Greek kingdoms. When a diplomatic dispute between Rome and a Greek colony erupted into a naval confrontation, the Greek colony appealed for military aid to Pyrrhus, ruler of the northwestern Greek kingdom of Epirus. Motivated by a personal desire for military accomplishment, Pyrrhus landed a Greek army of approximately 25,000 men on Italian soil in 280 BCE. Despite early victories, Pyrrhus found his position in Italy untenable. Rome steadfastly refused to negotiate with Pyrrhus as long as his army remained in Italy. Facing unacceptably heavy losses with each encounter with the Roman army, Pyrrhus withdrew from the peninsula (thus giving rise to the term “pyrrhic victory”).

In 275 BCE, Pyrrhus again met the Roman army at the Battle of Beneventum. While Beneventum’s outcome was indecisive, it led to Pyrrhus’s

complete withdrawal from Italy, due to the decimation of his army following years of foreign campaigns, and the diminishing likelihood of further material gains. These conflicts with Pyrrhus would have a positive effect on Rome. Rome had shown it was capable of pitting its armies successfully against the dominant military powers of the Mediterranean, and that the Greek kingdoms were incapable of defending their colonies in Italy and abroad. Rome quickly moved into southern Italia, subjugating and dividing the Greek colonies. By the middle of the 3rd century, Rome effectively dominated the Italian peninsula, and had won an international military reputation.

Mid-Republic

Punic Wars

The First Punic War began in 264 BCE, when Rome and Carthage became interested in using settlements within Sicily to solve their own internal conflicts. The war saw land battles in Sicily early on, but focus soon shifted to naval battles around Sicily and Africa. Before the First Punic War, there was essentially no Roman navy. The new war in Sicily against Carthage, a great naval power, forced Rome to quickly build a fleet and train sailors. Though the first few naval battles of the First Punic War were catastrophic disasters for Rome, Rome was eventually able to beat the Carthaginians and leave them without a fleet or sufficient funds to raise another. For a maritime power, the loss of Carthage’s access to the Mediterranean stung financially and psychologically, leading the Carthaginians to sue for peace.

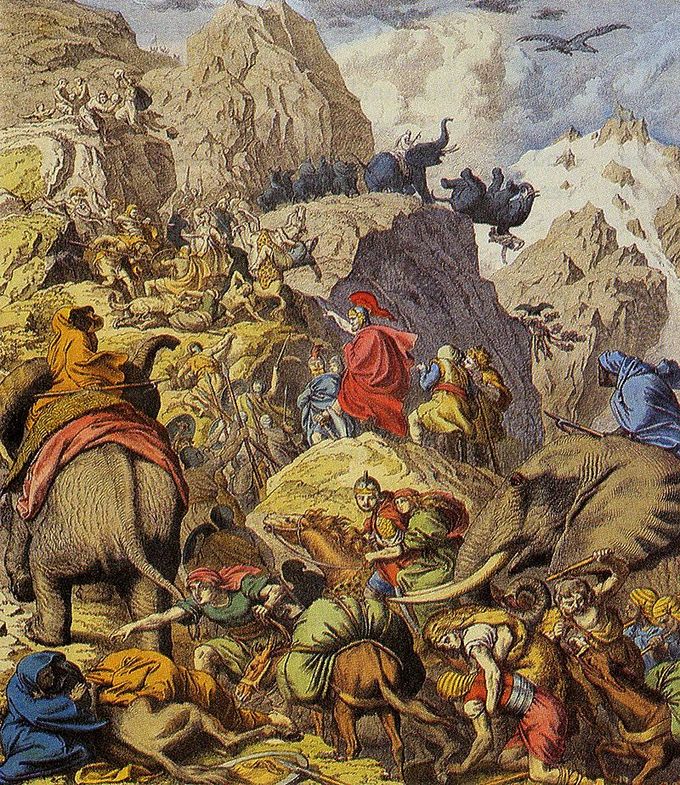

Continuing distrust led to the renewal of hostilities in the Second Punic War, when, in 218 BCE, Carthaginian commander Hannibal attacked a Spanish town with diplomatic ties to Rome. Hannibal then crossed the Italian Alps to invade Italy. Hannibal’s successes in Italy began immediately, but his brother, Hasdrubal, was defeated after he crossed the Alps on the Metaurus River. Unable to defeat Hannibal on Italian soil, the Romans boldly sent an army to Africa under Scipio Africanus, with the intention of threatening the Carthaginian capital. As a result, Hannibal was recalled to Africa, and defeated at the Battle of Zama.

Carthage never managed to recover after the Second Punic War, and the Third Punic War that followed was, in reality, a simple punitive mission to raze the city of Carthage to the ground. Carthage was almost defenseless, and when besieged offered immediate surrender, conceding to a string of outrageous Roman demands. The Romans refused the surrender and the city was stormed and completely destroyed after a short siege. Ultimately, all of Carthage’s North African and Spanish territories were acquired by Rome.

Macedon and Greece

Rome’s preoccupation with its war in Carthage provided an opportunity for Philip V of the kingdom of Macedonia, located in the northern part of the Greek peninsula, to attempt to extend his power westward. Over the next several decades, Rome clashed with Macedon to protect their Greek allies throughout the First, Second, and Third Macedonian Wars. By 168 BCE, the Macedonians had been thoroughly defeated, and Rome divided the Macedonian Kingdom into four client republics. After a Fourth Macedonian War, and nearly a century of constant crisis management in Greece (which almost always was a result of internal instability when Rome pulled out), Rome decided to divide Macedonia into two new Roman provinces, Achaea and Epirus.

Crises of the Republic

The 1st century BCE saw tensions between patricians and plebeians erupt into violence, as the Republic became increasingly more divided and unstable.

Learning Objectives

Explain how crises in the 1st century BCE further destabilized the Roman Republic

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Though the causes and attributes of individual crises varied throughout the decades, an underlying theme of conflict between

the aristocracy and ordinary citizens drove the majority of actions. - The Gracchi brothers, Tiberius and Gaius, introduced a number of populist agrarian and land reforms in the 130s and 120s BCE that were heavily opposed by the patrician Senate. Both brothers were murdered by mob violence after political stalemates.

- Political instability continued, as populist Marius and optimate Sulla engaged in a series of conflicts that culminated in Sulla seizing power and marching to Asia Minor against the decrees of the Senate, and Marius seizing power in a coup back at Rome.

- The Catilinarian Conspiracy discredited the populist party, in turn repairing the image of the Senate, which had come to be seen as weak and not worthy of such violent attack.

- Under the terms of the First Triumvirate, Pompey ’s arrangements would be ratified and Caesar would be elected consul in 59 BCE; he subsequently served as governor of Gaul for five years. Crassus was promised the consulship later.

- The triumvirate crumbled in the wake of growing political violence and Crassus and Caesar’s daughter’s death.

- A resolution was passed by the Senate that declared that if Caesar did not lay down his arms by July 49 BCE, he would be considered an enemy of the Republic. Meanwhile, Pompey was granted dictatorial powers over the Republic.

- On January 10, 49 BCE, Caesar crossed the Rubicon and marched towards Rome. Pompey, the consuls, and the Senate all abandoned Rome for Greece, and Caesar entered the city unopposed.

Key Terms

- Gracchi Brothers: Brothers Tiberius and Gaius, Roman plebeian nobiles who both served as tribunes in the late 2nd century BCE. They attempted to pass land reform legislation that would redistribute the major patrician landholdings among the plebeians.

- plebeian: A general body of free Roman citizens who were

part of the lower strata of society. - patrician: A group of ruling class families in ancient Rome.

The Crises of the Roman Republic refers to an extended period of political instability and social unrest that culminated in the demise of the Roman Republic, and the advent of the Roman Empire from about 134 BCE-44 BCE. The exact dates of this period of crisis are unclear or are in dispute from scholar to scholar. Though the causes and attributes of individual crises varied throughout the decades, an underlying theme of conflict between the aristocracy and ordinary citizens drove the majority of actions.

Optimates were a traditionalist majority of the late Roman Republic. They wished to limit the power of the popular assemblies and the Tribune of the Plebeians, and to extend the power of the Senate, which was viewed as more dedicated to the interests of the aristocrats. In particular, they were concerned with the rise of individual generals, who, backed by the tribunate, the assemblies, and their own soldiers, could shift power from the Senate and aristocracy. Many members of this faction were so-classified because they used the backing of the aristocracy and the Senate to achieve personal

goals, not necessarily because they favored the aristocracy over the lower classes. Similarly, the populists did not necessarily champion the lower classes, but often used their support to achieve personal goals.

Following a period of great military successes and economic failures of the early Republican period, many plebeian calls for reform among the classes had been quieted. However, many new slaves were being imported from abroad, causing an unemployment crisis among the lower classes. A flood of unemployed citizens entered Rome, giving rise to populist ideas throughout the city.

The Gracchi Brothers

Tiberius Gracchus took office as a tribune of the plebeians in late 134 BCE. At the time, Roman society was a highly stratified class system with tensions bubbling below the surface. This system consisted of noble families of the senatorial rank (patricians), the knight or equestrian class, citizens (grouped into two or three classes of self-governing allies of Rome: landowners; and plebs, or tenant freemen, depending on the time period), non-citizens who lived outside of southwestern Italy, and at the bottom, slaves. The government owned large tracts of farm land that it had gained through invasion or escheat. This land was rented out to either large landowners whose slaves tilled the land, or small tenant farmers who occupied the property on the basis of a sub-lease. Beginning in 133 BCE, Tiberius tried to redress the grievances of displaced small tenant farmers. He bypassed the Roman Senate, and passed a law limiting the amount of land belonging to the state that any individual could farm, which resulted in the dissolution of large plantations maintained by rich landowners on public land.

A political back-and-forth ensued in the Senate as the other tribune, Octavius, blocked Tiberius’s initiatives, and the Senate denied funds needed for land reform. When Tiberius sought re-election to his one-year term (an unprecedented action), the oligarchic nobles responded by murdering Tiberius, and mass riots broke out in the city in reaction to the assassination. About nine years later, Tiberius Gracchus’s younger brother, Gaius, passed more radical reforms in favor of the poorer plebeians. Once again, the situation ended in violence and murder as Gaius fled Rome and was either murdered by oligarchs or committed suicide. The deaths of the Gracchi brothers marked the beginning of a late Republic trend in which tensions and conflicts erupted in violence.

Marius and Sulla

The next major reformer of the time was Gaius Marius, who like the Gracchi, was a populist who championed the lower classes. He was a general who abolished the property requirement for becoming a soldier, which allowed the poor to enlist in large numbers. Lucius Cornelius Sulla was appointed as Marius’s quaestor (supervisor of the financial affairs of the state) in 107 BCE, and later competed with Marius for supreme power. Over the next few decades, he and Marius engaged in a series of conflicts that culminated in Sulla seizing power and marching to Asia Minor against the decrees of the Senate. Marius launched a coup in Sulla’s absence, putting to death some of his enemies and instituting a populist regime, but died soon after.

Pompey, Crassus, and the Catilinarian Conspiracy

In 77 BCE, two of Sulla’s former lieutenants, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (“Pompey the Great”) and Marcus Licinius Crassus, had left Rome to put down uprisings and found the populist party, attacking Sulla’s constitution upon their return. In an attempt to forge an agreement with the populist party, both lieutenants promised to dismantle components of Sulla’s constitution that the populists found disagreeable, in return for being elected consul. The two were elected in 70 BCE and held true to their word. Four years later, in 66 BCE, a movement to use peaceful means to address the plights of the various classes arose; however, after several failures in achieving their goals, the movement, headed by Lucius Sergius Catilina and based in Faesulae, a hotbed of agrarian agitation, decided to march to Rome and instigate an uprising. Marcus Tullius Cicero, the consul at the time, intercepted messages regarding recruitment and plans, leading the Senate to authorize the assassination of many Catilinarian conspirators in Rome, an action that was seen as stemming from dubious authority. This effectively disrupted the conspiracy and discredited the populist party, in turn repairing the image of the Senate, which had come to be seen as weak and not worthy of such violent attack.

First Triumvirate

In 62 BCE, Pompey returned from campaigning in Asia to find that the Senate, elated by its successes against the Catiline conspirators, was unwilling to ratify any of Pompey’s arrangements, leaving Pompey powerless. Julius Caesar returned from his governorship in Spain a year later and, along with Crassus, established a private agreement with Pompey known as the First Triumvirate. Under the terms of this agreement, Pompey’s arrangements would be ratified and Caesar would be elected consul in 59 BCE, subsequently serving as governor of Gaul for five years. Crassus was promised the consulship later.

When Caesar became consul, he saw the passage of Pompey’s arrangements through the Senate, at times using violent means to ensure their passage. Caesar also facilitated the election of patrician Publius Clodius Pulcher to the tribunate in 58 BCE, and Clodius sidelined Caesar’s senatorial opponents, Cato and Cicero. Clodius eventually formed armed gangs that terrorized Rome and began to attack Pompey’s followers, who formed counter-gangs in response, marking the end of the political alliance between Pompey and Caeser. Though the triumvirate was briefly renewed in the face of political opposition for the consulship from Domitius Ahenobarbus, Crassus’s death during an expedition against the Kingdom of Parthia, and the death of Pompey’s wife, Julia, who was also Caesar’s daughter, severed any remaining bonds between Pompey and Caesar.

Beginning in the summer of 54 BCE, a wave of political corruption and violence swept Rome, reaching a climax in January 52 BCE, when Clodius was murdered in a gang war. Caesar presented an ultimatum to the Senate on January 1, 49 BCE, which was ultimately rejected. Subsequently, a resolution was passed that declared that if Caesar did not lay down his arms by July, he would be considered an enemy of the Republic. The senators adopted Pompey as their champion, and on January 7, Pompey was granted dictatorial powers over the Republic by the Senate. Pompey’s army, however, was composed mainly of untested conscripts, and on January 10, Caesar crossed the Rubicon with his more experienced forces in defiance of Roman laws, and marched towards Rome. Pompey, the consuls, and the Senate all abandoned Rome for Greece, in the face of Caeser’s rapidly advancing forces, and Caesar entered the city unopposed.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Roman Republic. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Republic. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Interrex. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interrex. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Overthrow of the Roman monarchy. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Overthrow_of_the_Roman_monarchy. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Roman Kingdom. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Kingdom. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- N03Brutus-u-Lucretia.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:N03Brutus-u-Lucretia.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Tizian_094.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tizian_094.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Senate of the Roman Republic. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Senate_of_the_Roman_Republic. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Constitution of the Roman Republic. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constitution_of_the_Roman_Republic. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- N03Brutus-u-Lucretia.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:N03Brutus-u-Lucretia.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Tizian_094.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tizian_094.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Curia Iulia - The Roman Senate House. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Senate%23mediaviewer/File:Curia_Iulia.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Roman SPQR Banner. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spqr%23mediaviewer/File:Roman_SPQR_banner.svg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Roman Republic. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Republic. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Social class in ancient Rome. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_class_in_ancient_Rome. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Conflict of the Orders. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conflict_of_the_Orders. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Lex Licinia Sextia. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lex_Licinia_Sextia. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Lex Trebonia (448 BC). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lex_Trebonia_(448_BC). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- N03Brutus-u-Lucretia.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:N03Brutus-u-Lucretia.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Tizian_094.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tizian_094.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Curia Iulia - The Roman Senate House. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Senate%23mediaviewer/File:Curia_Iulia.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Roman SPQR Banner. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spqr%23mediaviewer/File:Roman_SPQR_banner.svg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Gaius_Gracchus_Tribune_of_the_People.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gaius_Gracchus_Tribune_of_the_People.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Roman art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Roman Republic: The arts. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Republic#The_arts. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- N03Brutus-u-Lucretia.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:N03Brutus-u-Lucretia.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Tizian_094.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tizian_094.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Curia Iulia - The Roman Senate House. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Senate%23mediaviewer/File:Curia_Iulia.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Roman SPQR Banner. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spqr%23mediaviewer/File:Roman_SPQR_banner.svg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Gaius_Gracchus_Tribune_of_the_People.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gaius_Gracchus_Tribune_of_the_People.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Pompeius. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pompejus.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cicero - Musei Capitolini. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cicero%23mediaviewer/File:Cicero_-_Musei_Capitolini.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Old man Vatican. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Old_man_vatican_pushkin01.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Punic Wars. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Punic_Wars. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Roman Republic. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Republic. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- N03Brutus-u-Lucretia.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:N03Brutus-u-Lucretia.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Tizian_094.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tizian_094.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Curia Iulia - The Roman Senate House. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Senate%23mediaviewer/File:Curia_Iulia.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Roman SPQR Banner. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spqr%23mediaviewer/File:Roman_SPQR_banner.svg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Gaius_Gracchus_Tribune_of_the_People.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gaius_Gracchus_Tribune_of_the_People.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Pompeius. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pompejus.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cicero - Musei Capitolini. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cicero%23mediaviewer/File:Cicero_-_Musei_Capitolini.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Old man Vatican. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Old_man_vatican_pushkin01.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Depiction of Hannibal. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Punic_Wars%23mediaviewer/File:Hannibal3.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Roman Conquest of Italy. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Roman_conquest_of_Italy.PNG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Roman Republic. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Republic. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Plebs. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plebs. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Sulla. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sulla. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Crisis of the Roman Republic. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crisis_of_the_Roman_Republic. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Gracchi. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gracchi. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- plebeian. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/plebeian. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- patrician. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/patrician. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- N03Brutus-u-Lucretia.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:N03Brutus-u-Lucretia.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Tizian_094.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tizian_094.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Curia Iulia - The Roman Senate House. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Senate%23mediaviewer/File:Curia_Iulia.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Roman SPQR Banner. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spqr%23mediaviewer/File:Roman_SPQR_banner.svg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Gaius_Gracchus_Tribune_of_the_People.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gaius_Gracchus_Tribune_of_the_People.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Pompeius. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pompejus.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Cicero - Musei Capitolini. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cicero%23mediaviewer/File:Cicero_-_Musei_Capitolini.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Old man Vatican. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Old_man_vatican_pushkin01.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Depiction of Hannibal. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Punic_Wars%23mediaviewer/File:Hannibal3.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Roman Conquest of Italy. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Roman_conquest_of_Italy.PNG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Sulla Glyptothek Munich. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sulla%23mediaviewer/File:Sulla_Glyptothek_Munich_309.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Gaius Gracchus Tribune of the People. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gracchi%23mediaviewer/File:Gaius_Gracchus_Tribune_of_the_People.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright