13: Europe and North America in the Romantic Era (1789-1848)

- Page ID

- 219616

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

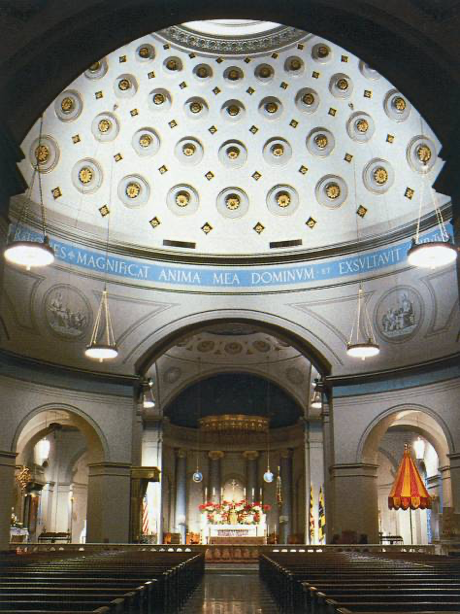

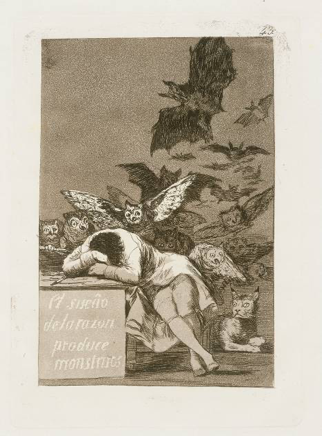

The Age of Enlightenment had much promise, but changing established institutions is a very tall task. Lord Acton writes to Bishop Creighton that the same moral standards should be applied to all men, political and religious leaders included, especially since “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely” (1887). We see this play out in France where Napoleon will lead armies all across Europe bringing devastation and the horrors of war. In America, George Washington, after the victory over the British army will become the first president in this fledgling democracy. He steps down after his term ensuring the newly formed United States of America will not become a European styled monarchy. Entering Spain, Napoleonic forces will murder, mutilate, rape, and ravage the people and the land. Francisco Goya will document this horror in his series of paintings and prints. The French forces form firing squads for those who resist, while the Catholic church in the distance remains conspicuously quiet with its lack of illumination. The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters by Goya reflects the lack of pushback against Napoleon at this time.

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters by Goya

The Third of May, 1808 Francisco Goya

Fearing the French troops will execute the Spanish royalty, Spaniards rise up. The rebels are rounded up and executed in the early morning hours. Goya shows the firing squad carrying out the execution orders as the Spaniards are highlighted. The central figure in white is illuminated and has his arms outstretched as if on the cross. The Catholic church in the distance remains quiet and in the dark as this horrific event takes place.

Saturn Devouring His Son, Goya

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/goya/hd_goya.htm

https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/artists/francisco-de-goya

Romanticism

What we also see during this period is an interest in the power of nature and man's struggles and place in the natural world. Themes of death and destruction, and struggles against the powerful forces of nature are painted. This is also a time when authors and visual artists begin exploring the same themes in their work. The European romantic novels will differ somewhat from the darker romantic writings of authors in America such as Edgar Allen Poe.

Two types of landscape paintings emerge during the Romantic Period. One type emphasizes the tranquility and beauty of nature. Paintings by the British painter John Constable, like the one below, place emphasis experiences he had growing up in the Stour Valley. Although he trained at the Royal Academy, he was disenchanted by the formulaic approaches taught at the school. Returning home, he studied the subtleties of the landscapes and skies around him and painted them with a sensitivity to the changing atmosphere and lighting. His approach was more scientific, logical, and connected than some of his contemporaries.

Another major British landscape painter of the time is Joseph Mallord William Turner. Turner painted monumental scenes in a grand style with historical references. History painting was considered the high mark in painting and Turner approaches landscapes in the same manner. Following the writings of Burke, he nfuses the concept of the sublime into his works. They are indeed grand, filled with the awe-inspiring violence only nature can produce at the time.

Snowstorm: Hannibal and His Army Crossing the Alps. 1812 Turner

Turner shows the enormous power of nature and the folly of empires with the painting featuring Hannibal's army being pummeled by a snowstorm. The concept of the sublime is expressed and is the over-ridding theme to the work. Both France and England vied for supremacy at the time, so the painting can also be seen as a rebuke towards these two competing nations.

The Slave Ship Turner 1840

The Monk by the Sea, 1810 Caspar David Friedrich

https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/caspar-david-friedrich-the-soul-of-nature

https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/person/103KQF

Abbey in an Oak Forest, 1809-10 Caspar David Friedrich

https://www.cnn.com/2024/01/30/style/caspar-david-friedrich-painter-tan/index.html

The Oxbow, 1836 Thomas Cole

https://smarthistory.org/cole-the-oxbow/

Portrait of Napoleon on His Imperial Throne, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres 1806

Grande Odalisque, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres 1814

Artists often have the desire to create original works, not just imitate nature. Exaggeration of forms, shapes, and the human body is one way to create something original and Ingres does this in the painting Grande Odalisque. Richly painted, it is an intellectually erotic experience through the carefully manipulated parts of the female form. Stretching and elongating the spine and right arm to create a sensual curve, Ingres presents his interpretation of the sensual odalisque, or harem woman. She looks back at us, the viewer, with a calm, cool glance engaging us and connecting us with the work. It is precisely painted in a Neoclassical style with a twist. Thoughtful, creative, intellectual manipulation of forms and proportions make it more sensual to the eye.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436708

https://www.frick.org/art/artists/ingres

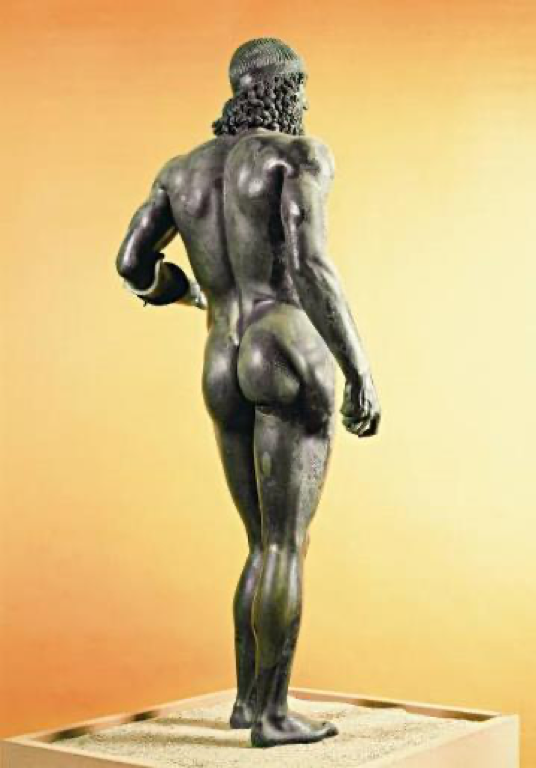

Riace Bronzes (460-420 BCE)

The Riace Bronzes do not have a sacrum (large “v-shaped” bone at the base of the spine). Also, their musculature and body creases between muscle masses are exaggerated. They are “more human than human."

In the reclining nude painted by Ingres, there are several vertebrae added to the lumbar spine. This lengthens her torso. Also, her arms appear more flexible, almost as if the underlying bony structure is missing – look at her elbow region and see if you agree. All of this done intentionally to make her more sensual than a woman with normal proportions. Artists often feel the need to exaggerate, or bring additional creativity to depictions of the human body.

Napoleon in the Pesthouse at Jaffa, March 11, 1799 Antoine-Jean Gros 1804

The Raft of the Medusa, Théodore Géricault 1818-19

Portrait of an Insane Man, Théodore Géricault 1822-23

Scenes From the Massacre at Chios, Eugène Delacroix 1824

Death of Sardanapalus, Eugène Delacroix 1827

Women of Algiers, Eugène Delacroix 1834

View of Rome, The Bridge and Castel Sant' Angelo with the Cupola of St. Peter's, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot 1826-27