The Benedictine Rule

- Page ID

- 108478

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The introduction has been prepared by John Terry (2021) and is based on the translation of Leonard Doyle, Saint Benedict's Rule for Monasteries (Collegeville, MN: The Order of St. Benedict, 1948). Excerpts have been adapted from Project Gutenberg.

Who was Benedict of Nursia?

Outside of the Bible itself, the Rule of Benedict is probably among the best-known Christian texts. The text itself concerns the proper organization of a monastic institution, including rules on silence, fasting, collective prayer, manual labor, travel, sin, and many other topics. It was written by Benedict of Nursia in or around the 540s and, while its popularity amongst monastic communities was probably slow to develop, it rose to prominence under the monastic reforms of the Carolingian1 regime in the ninth century and has only grown in significance since then.

We know very little about Benedict. He was born sometime around 480 in central Italy and, according to a brief account written by Pope Gregory I (r. 590-604), as a young man he decided to become a hermit away from traditional society near Subiaco. According to Gregory he founded several monasteries (twelve of them, each with twelve monks plus an abbot), and settled at Monte Cassino in southern Italy. There he took over the site of an ancient temple Apollo and founded his most famous monastic community. It was at Monte Cassino that Benedict probably wrote his Rule.

Monastic Context

By the time Benedict established the community at Monte Cassino, monastic practice was entering its third century. Drawing on a diverse tradition from north Africa and west Asia, Benedict appears to have been weighing the best practices of a vast spectrum of monastic life from the communal to the harshly ascetic. Asceticism–that is, solitary or semi-solitary life focused on fasting, bodily denial, and prayer––has its gold standard in this period with Antony of Egypt (c. 251-356), who withdrew to the Egyptian desert and whose life was commemorated with a biography written by the bishop Athanasius (dates). Eventually communities followed Antony’s example, establishing so-called cenobitic monasticism.2 Combined with the rules of Pachomius (c. 292-246), Basil of Caesarea (c. 330-379), and Augustine (c. 354-430) by the time of Benedict “there was a considerable literature on ways to live a Christian monastic life.”3

Life in a monastic institution varied. Some monasteries were wealthy, meaning that large areas of surrounding land belonged to that monastery's administrators, who often rented parcels of those lands out to individuals. Other monasteries were remote and poor by design. Most monastic institutions, regardless of whether or not they used Benedict's "little rule," adhered to practices such as set times for prayers and worship, expectations for manual and intellectual labor, and common property. It is clear from Benedict's introductory remarks below that he was attempting to split the difference between the harshest and most casual monastic practices of which he was aware in the sixth-century Mediterranean region.

Check Sarah Foot, Anglo-Saxon Monasticism

Peter Brown, western Christendom has some notes on Benedict’s time

Walafrid Strabo on gardening/agriculture

Contents of the rule

It’s important to note that while “the language of the Rule is generally simple, its exposition straightforward,”4 access to the text’s meaning depends entirely on having some context for the rise of monasticism during the period––both its spiritual allure and social function as a center of higher education for nobles in many cases. Increasingly across the fourth and fifth centuries, monasteries were seen as suitable places for education and social climbing in an “intensely status-conscious society”5 and they needed to be run with specific regulations. To accomplish this, Gregory I credited “Benedict’s unfailing sense of measure and his spiritual insight. Here was an abbot of inspired certainty of touch, who knew ho to lead his tiny flock of monks through every spiritual and material emergency. And he had done this by exacting absolute obedience. Each monk was bound to his abbot and to his fellows by an awesome code that was summed up in a single phrase: obedientia sine mora, ‘obedience without a moment’s hesitation’.”6

This helps us understand why Benedict approaches monastic regulation with the seriousness he believed it deserved, loosely organized his Rule into short sections loosely related by themes such as:

- Penance––that is, actions to be undertaken to deal with sin

- Character of monastic leadership, such as abbots and abbesses (the leaders of monasteries) and other officers such as porters and cooks

- Types of worship––prayer, communal worship, and when these are to be done

- The role and types of labor expected of monks

To get a sense of what is in the Rule before reading excerpts, here is the table of contents with links to their sections. Chapters included below are in bold. For discussion and response, what other types of themes do you see, and what do you think is the logic behind them?

Footnotes

[1] The Carolingians were a dynastic ruling family in the kingdom of Francia in the former Roman province of Gaul, roughly corresponding with what is today France.

[2] This term comes from the Greek phrase koinos bios, or "common life."

[3] Bruce Venarde, trans. and ed., The Rule of St. Benedict (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011), ix.

[4] Venarde, Rule, xii.

[5] Peter Brown, The Rise of Western Christendom (London: Blackwell, 2003), 225.

[6] Brown, Christendom, 210.

Excerpts

General response questions (note that there are also response questions for each section, so that this text can be adapted for various needs in the classroom):

1) Stabilitas, or "stability," is a chief concern of Benedict's. What various forms does this concept take in the Rule, and why is this?

2) What does this Rule tell us about the world in which Benedict lived? What does it tell us about the world he wanted to make?

Chapter 1: On the Kinds of Monks

It is well known that there are four kinds of monks. The first kind are the Cenobites: those who live in monasteries and serve under a rule and an Abbot. The second kind are the Anchorites or Hermits: those who, no longer in the first fervor of their reformation, but after long probation in a monastery, having learned by the help of many brethren how to fight against the devil, go out well armed from the ranks of the community to the solitary combat of the desert. They are able now, with no help save from God, to fight single-handed against the vices of the flesh and their own evil thoughts. The third kind of monks, a detestable kind, are the Sarabaites.1 These, not having been tested, as gold in the furnace (Wis. 3:6), by any rule or by the lessons of experience, are as soft as lead. In their works they still keep faith with the world, so that their tonsure2 marks them as liars before God. They live in twos or threes, or even singly, without a shepherd, in their own sheepfolds and not in the Lord's. Their law is the desire for self-gratification: whatever enters their mind or appeals to them, that they call holy; what they dislike, they regard as unlawful. The fourth kind of monks are those called Gyrovagues.3 These spend their whole lives tramping from province to province, staying as guests in different monasteries for three or four days at a time. Always on the move, with no stability,4 they indulge their own wills and succumb to the allurements of gluttony, and are in every way worse than the Sarabaites. Of the miserable conduct of all such it is better to be silent than to speak. Passing these over, therefore, let us proceed, with God's help, to lay down a rule for the strongest kind of monks, the Cenobites.

Chapter 2: What Kind of Person the Abbess Ought to Be

An Abbess5 who is worthy to be over a monastery should always remember what she is called, and live up to the name of Superior. For she is believed to hold the place of Christ in the monastery, being called by a name of His, which is taken from the words of the Apostle: "You have received a Spirit of adoption ..., by virtue of which we cry, 'Abba -- Father'" (Rom. 8:15)! Therefore the Abbess ought not to teach or ordain or command anything which is against the Lord's precepts; on the contrary, her commands and her teaching should be a leaven of divine justice kneaded into the minds of her disciples. Let the Abbess always bear in mind that at the dread Judgment of God there will be an examination of these two matters: her teaching and the obedience of her disciples. And let the Abbess be sure that any lack of profit the master of the house may find in the sheep will be laid to the blame of the shepherd. On the other hand, if the shepherd has bestowed all her pastoral diligence on a restless, unruly flock and tried every remedy for their unhealthy behavior, then she will be acquitted at the Lord's Judgment and may say to the Lord with the Prophet: "I have not concealed Your justice within my heart; Your truth and Your salvation I have declared" (Ps. 39[40]:11)."But they have despised and rejected me" (Is. 1:2; Ezech. 20:27). And then finally let death itself, irresistible, punish those disobedient sheep under her charge.

- Why does Benedict discuss various types of monks?

- For what reasons does Benedict reject certain types of monastic practice?

Chapter 5: On Obedience

The first degree of humility is obedience without delay. This is the virtue of those who hold nothing dearer to them than Christ; who, because of the holy service they have professed, and the fear of hell, and the glory of life everlasting, as soon as anything has been ordered by the Superior, receive it as a divine command and cannot suffer any delay in executing it. Of these the Lord says, "As soon as he heard, he obeyed Me" (Ps. 17[18]:45). And again to teachers He says, "He who hears you, hears Me" (Luke 10:16). Such as these, therefore, immediately leaving their own affairs and forsaking their own will, dropping the work they were engaged on and leaving it unfinished, with the ready step of obedience follow up with their deeds the voice of him who commands. And so as it were at the same moment the master's command is given and the disciple's work is completed, the two things being speedily accomplished together in the swiftness of the fear of God by those who are moved with the desire of attaining life everlasting. That desire is their motive for choosing the narrow way, of which the Lord says, "Narrow is the way that leads to life" (Matt. 7:14), so that, not living according to their own choice nor obeying their own desires and pleasures but walking by another's judgment and command, they dwell in monasteries and desire to have an Abbot over them. Assuredly such as these are living up to that maxim of the Lord in which He says, "I have come not to do My own will, but the will of Him who sent Me" (John 6:38). But this very obedience will be acceptable to God and pleasing to all only if what is commanded is done without hesitation, delay, lukewarmness, grumbling, or objection. For the obedience given to Superiors is given to God, since He Himself has said, "He who hears you, hears Me" (Luke 10:16). And the disciples should offer their obedience with a good will, for "God loves a cheerful giver" (2 Cor. 9:7). For if the disciple obeys with an ill will and murmurs, not necessarily with his lips but simply in his heart, then even though he fulfill the command yet his work will not be acceptable to God, who sees that his heart is murmuring. And, far from gaining a reward for such work as this, he will incur the punishment due to murmurers, unless he amend and make satisfaction.

Chapter 6: On the Spirit of Silence

Let us do what the Prophet says: "I said, 'I will guard my ways, that I may not sin with my tongue. I have set a guard to my mouth.' I was mute and was humbled, and kept silence even from good things" (Ps. 38[39]:2-3). Here the Prophet shows that if the spirit of silence ought to lead us at times to refrain even from good speech, so much the more ought the punishment for sin make us avoid evil words. Therefore, since the spirit of silence is so important, permission to speak should rarely be granted even to perfect disciples, even though it be for good, holy edifying conversation; for it is written, "In much speaking you will not escape sin" (Prov. 10:19), and in another place, "Death and life are in the power of the tongue" (Prov. 18:21). For speaking and teaching belong to the mistress; the disciple's part is to be silent and to listen. And for that reason if anything has to be asked of the Superior, it should be asked with all the humility and submission inspired by reverence. But as for coarse jests and idle words or words that move to laughter, these we condemn everywhere with a perpetual ban, and for such conversation we do not permit a disciple to open her mouth.

- What is the link between obedience and silence?

- Does Benedict demand absolute silence of monks? Why or why not?

Chapter 22: How the Sisters Are to Sleep

Let each one sleep in a separate bed. Let them receive bedding suitable to their manner of life, according to the Abbess's directions.6 If possible let all sleep in one place; but if the number does not allow this, let them take their rest by tens or twenties with the seniors who have charge of them. A candle shall be kept burning in the room until morning. Let them sleep clothed and girded with belts or cords--but not with their knives at their sides, lest they cut themselves in their sleep--and thus be always ready to rise without delay when the signal is given and hasten to be before one another at the Work of God, yet with all gravity and decorum. The younger shall not have beds next to one another, but among those of the older ones. When they rise for the Work of God let them gently encourage one another, that the drowsy may have no excuse.

Chapter 23: On Excommunication for Faults

If a brother is found to be obstinate, or disobedient, or proud, or murmuring, or habitually transgressing the Holy Rule in any point and contemptuous of the orders of his seniors, the latter shall admonish him secretly a first and a second time, as Our Lord commands (Matt. 18:15). If he fails to amend, let him be given a public rebuke in front of the whole community. But if even then he does not reform, let him be placed under excommunication, provided that he understands the seriousness of that penalty; if he is perverse, however, let him undergo corporal punishment.

Chapter 24: What the Measure of Excommunication Should Be

The measure of excommunication or of chastisement should correspond to the degree of fault,

which degree is estimated by the judgment of the Abbess. If a sister is found guilty of lighter faults, let her be excluded from the common table. Now the program for one deprived of the company of the table shall be as follows: In the oratory she shall intone neither Psalm nor antiphon nor shall she recite a lesson until she has made satisfaction; in the refectory she shall take her food alone after the community meal, so that if they eat at the sixth hour, for instance, that sister shall eat at the ninth, while if they eat at the ninth hour she shall eat in the evening, until by a suitable satisfaction she obtains pardon.

Chapter 25: On Weightier Faults

Let the brother who is guilty of a weightier fault be excluded both from the table and from the oratory. Let none of the brethren join him either for company or for conversation. Let him be alone at the work assigned him, abiding in penitential sorrow and pondering that terrible sentence of the Apostle where he says that a man of that kind is handed over for the destruction of the flesh, that the spirit may be saved in the day of the Lord (1 Cor. 5:5). Let him take his meals alone in the measure and at the hour which the Abbot shall consider suitable for him. He shall not be blessed by those who pass by, nor shall the food that is given him be blessed.

- Why are monks to sleep separately?

- Review chapter 22 and read footnote 6. This is an example in which Benedict appears to be ambiguous in his instruction. Why do you think this is?

- Reflect upon or discuss what you think "excommunication" means. Is Benedict referring to formal excommunication––that is, separation from communion––or is he describing something different?

Chapter 30: How Boys Are to Be Corrected

Every age and degree of understanding should have its proper measure of discipline. With regard to boys and adolescents, therefore, or those who cannot understand the seriousness of the penalty of excommunication, whenever such as these are delinquent let them be subjected to severe fasts or brought to terms by harsh beatings, that they may be cured.

- What does this short chapter tell us about the nature of the Rule? Is it absolutely rigid or flexible? What other examples support your answer?

Chapter 32: On the Tools and Property of the Monastery

For the care of the monastery's property in tools, clothing and other articles let the Abbess appoint sisters on whose manner of life and character she can rely; and let her, as she shall judge to be expedient, consign the various articles to them, to be looked after and to be collected again. The Abbess shall keep a list of these articles, so that as the sisters succeed one another in their assignments she ma m,y know what she gives and what she receives back. If anyone treats the monastery's property in a slovenly or careless way, let her be corrected. If she fails to amend, let her undergo the discipline of the Rule.

Chapter 33: Whether Monks Ought to Have Anything of Their Own

This vice especially is to be cut out of the monastery by the roots. Let no one presume to give or receive anything without the Abbot's leave, or to have anything as his own--anything whatever, whether book or tablets or pen or whatever it may be--since they are not permitted to have even their bodies or wills at their own disposal; but for all their necessities let them look to the Father of the monastery. And let it be unlawful to have anything which the Abbot has not given or allowed. Let all things be common to all, as it is written (Acts 4:32), and let no one say or assume that anything is his own. But if anyone is caught indulging in this most wicked vice, let him be admonished once and a second time. If he fails to amend, let him undergo punishment.

- Taken together, what do these two chapters suggest about the role of the individual?

Chapter 39: On the Measure of Food

We think it sufficient for the daily dinner, whether at the sixth or the ninth hour, that every table have two cooked dishes on account of individual infirmities, so that he who for some reason cannot eat of the one may make his meal of the other. Therefore let two cooked dishes suffice for all the brethren; and if any fruit or fresh vegetables are available, let a third dish be added. Let a good pound weight of bread suffice for the day, whether there be only one meal or both dinner and supper. If they are to have supper, the cellarer shall reserve a third of that pound, to be given them at supper. But if it happens that the work was heavier, it shall lie within the Abbot's discretion and power, should it be expedient, to add something to the fare. Above all things, however, over-indulgence7 must be avoided and a monk must never be overtaken by indigestion; for there is nothing so opposed to the Christian character as over-indulgence according to Our Lord's words, "See to it that your hearts be not burdened with over-indulgence" (Luke 21:34). Young boys shall not receive the same amount of food as their elders, but less; and frugality shall be observed in all circumstances. Except the sick who are very weak, let all abstain entirely from eating the flesh of four-footed animals.

Chapter 40: On the Measure of Drink

"Everyone has her own gift from God, one in this way and another in that" (1 Cor. 7:7). It is therefore with some misgiving that we regulate the measure of others' sustenance. Nevertheless, keeping in view the needs of the weak, we believe that a hemina8 of wine a day is sufficient for each. But those to whom God gives the strength to abstain should know that they will receive a special reward. If the circumstances of the place, or the work or the heat of summer require a greater measure, the superior shall use her judgment in the matter, taking care always that there be no occasion for surfeit or drunkenness. We read it is true, that wine is by no means a drink for monastics; but since the monastics of our day cannot be persuaded of this let us at least agree to drink sparingly and not to satiety, because "wine makes even the wise fall away" (Eccles. 19:2). But where the circumstances of the place are such that not even the measure prescribed above can be supplied, but much less or none at all, let those who live there bless God and not murmur. Above all things do we give this admonition, that they abstain from murmuring.

Chapter 41: At What Hours the Meals Should Be Taken

From holy Easter until Pentecost let the brothers take dinner at the sixth hour and supper in the evening. From Pentecost throughout the summer, unless the monks have work in the fields let them fast on Wednesdays and Fridays until the ninth hour; on the other days let them dine at the sixth hour. This dinner at the sixth hour shall be the daily schedule if they have work in the fields or the heat of summer is extreme; the Abbot's foresight shall decide on this. Thus it is that he should adapt and arrange everything in such a way that souls may be saved and that the brethren may do their work without just cause for murmuring. From the Ides of September until the beginning of Lent let them always take their dinner at the ninth hour. In Lent until Easter let them dine in the evening. But this evening hour shall be so determined that they will not need the light of a lamp while eating, Indeed at all seasons let the hour, whether for supper or for dinner, be so arranged that everything will be done by daylight.

- Review chapter 39, footnote 7. Why does Bede use this particular Latin word (crapula) to describe excess in food and drink?

- Why does Benedict appear obsessive over the amounts and times of meals?

Chapter 42: That No One Speak After Compline

Monastics ought to be zealous for silence at all times, but especially during the hours of the night. For every season, therefore, whether there be fasting or two meals, let the program be as follows: If it be a season when there are two meals, then as soon as they have risen from supper they shall all sit together, and one of them shall read the Conferences or the Lives of the Fathers or something else that may edify the hearers; not the Heptateuch9 or the Books of Kings, however, because it will not be expedient for weak minds to hear those parts of Scripture at that hour; but they shall be read at other times. If it be a day of fast, then having allowed a short interval after Vespers they shall proceed at once to the reading of the Conferences, as prescribed above; four or five pages being read, or as much as time permits, so that during the delay provided by this reading all may come together, including those who may have been occupied in some work assigned them. When all, therefore, are gathered together, let them say Compline; and when they come out from Compline, no one shall be allowed to say anything from that time on. And if anyone should be found evading this rule of silence, let her undergo severe punishment. An exception shall be made if the need of speaking to guests should arise or if the Abbess should give someone an order. But even this should be done with the utmost gravity and the most becoming restraint.

Chapter 43: On Those Who Come Late to the Work of God or to Table

At the hour for the Divine Office, as soon as the signal is heard, let them abandon whatever they may have in hand and hasten with the greatest speed, yet with seriousness, so that there is no excuse for levity. Let nothing, therefore, be put before the Work of God. If at the Night Office anyone arrives after the "Glory be to the Father" of Psalm 94--which Psalm for this reason we wish to be said very slowly and protractedly--let him not stand in his usual place in the choir; but let him stand last of all, or in a place set aside by the Abbot for such negligent ones in order that they may be seen by him and by all. He shall remain there until the Work of God has been completed, and then do penance by a public satisfaction. the reason why we have judged it fitting for them so stand in the last place or in a place apart is that, being seen by all, they may amend for very shame. For if they remain outside of the oratory, there will perhaps be someone who will go back to bed and sleep or at least seat himself outside and indulge in idle talk, and thus an occasion will be provided for the evil one. But let them go inside, that they many not lose the whole Office, and may amend for the future. At the day Hours anyone who does not arrive at the Work of God until after the verse and the "Glory be to the Father" for the first Psalm following it shall stand in the last place, according to our ruling above. Nor shall he presume to join the choir in their chanting until he has made satisfaction, unless the Abbot should pardon him and give him permission; but even then the offender must make satisfaction for his fault. Anyone who does not come to table before the verse, so that all together may say the verse and the oration and all sit down to table at the same time--anyone who through his own carelessness or bad habit does not come on time shall be corrected for this up to the second time. If then he does not amend, he shall not be allowed to share in the common table, but shall be separated from the company of all and made to eat alone, and his portion of wine shall be taken away from him, until he has made satisfaction and has amended. And let him suffer a like penalty who is not present at the verse said after the meal. But if anyone is offered something by the Superior and refuses to take it, then when the time comes that he desires what he formerly refused or something else, let him receive nothing whatever until he has made proper satisfaction.

Chapter 44: How the Excommunicated Are to Make Satisfaction

One who for serious faults is excommunicated from oratory and table shall make satisfaction as follows. At the hour when the celebration of the Work of God is concluded in the oratory, let her lie prostrate before the door of the oratory, saying nothing, but only lying prone with her face to the ground at the feet of all as they come out of the oratory. And let her continue to do this until the Abbess judges that satisfaction has been made. Then, when she has come at the Abbess's bidding, let her cast herself first at the Abbess's feet and then at the feet of all, that they may pray for her. And next, if the Abbess so orders, let her be received into the choir, to the place which the Abbess appoints, but with the provision that she shall not presume to intone Psalm or lesson or anything else in the oratory without a further order from the Abbess. Moreover, at every Hour, when the Work of God is ended, let her cast herself on the ground in the place where she stands. And let her continue to satisfy in this way until the Abbess again orders her finally to cease from this satisfaction. But those who for slight faults are excommunicated only from table shall make satisfaction in the oratory, and continue in it till an order from the Abbess, until she blesses them and says, "It is enough."

Chapter 45: On Those Who Make Mistakes in the Oratory

When anyone has made a mistake while reciting a Psalm, a responsory, an antiphon or a lesson, if he does not humble himself there before all by making a satisfaction, let him undergo a greater punishment because he would not correct by humility what he did wrong through carelessness. But boys for such faults shall be whipped.

Chapter 46: On Those Who Fail in Any Other Matters

When anyone is engaged in any sort of work, whether in the kitchen, in the cellar, in a shop, in the bakery, in the garden, while working at some craft, or in any other place, and she commits some fault, or breaks something, or loses something, or transgresses in any other way whatsoever, if she does not come immediately before the Abbess and the community of her own accord to make satisfaction and confess her fault, then when it becomes known through another, let her be subjected to a more severe correction. But if the sin-sickness of the soul is a hidden one, let her reveal it only to the Abbess or to a spiritual mother, who knows how to cure her own and others' wounds without exposing them and making them public.

- Do you detect any flexibility in chapters 42-46 (especially chapter 44)? If so, what is the logic behind that flexibility?

- What is the role of stabilitas in these sections?

Chapter 48: On the Daily Manual Labor

Idleness is the enemy of the soul. Therefore the sisters should be occupied at certain times in manual labor, and again at fixed hours in sacred reading. To that end we think that the times for each may be prescribed as follows. From Easter until the Calends of October, when they come out from Prime in the morning let them labor at whatever is necessary until about the fourth hour, and from the fourth hour until about the sixth let them apply themselves to reading. After the sixth hour, having left the table, let them rest on their beds in perfect silence; or if anyone may perhaps want to read, let her read to herself in such a way as not to disturb anyone else. Let None be said rather early, at the middle of the eighth hour, and let them again do what work has to be done until Vespers. And if the circumstances of the place or their poverty should require that they themselves do the work of gathering the harvest, let them not be discontented; for then are they truly monastics when they live by the labor of their hands, as did our Fathers and the Apostles. Let all things be done with moderation, however, for the sake of the faint-hearted. From the Calends of October until the beginning of Lent, let them apply themselves to reading up to the end of the second hour. At the second hour let Terce be said, and then let all labor at the work assigned them until None. At the first signal for the Hour of None let everyone break off from her work, and hold herself ready for the sounding of the second signal. After the meal let them apply themselves to their reading or to the Psalms. On the days of Lent, from morning until the end of the third hour let them apply themselves to their reading, and from then until the end of the tenth hour let them do the work assigned them. And in these days of Lent they shall each receive a book from the library, which they shall read straight through from the beginning. These books are to be given out at the beginning of Lent. But certainly one or two of the seniors should be deputed to go about the monastery at the hours when the sisters are occupied in reading and see that there be no lazy sister who spends her time in idleness or gossip and does not apply herself to the reading, so that she is not only unprofitable to herself but also distracts others. If such a one be found (which God forbid), let her be corrected once and a second time; if she does not amend, let her undergo the punishment of the Rule in such a way that the rest may take warning. Moreover, one sister shall not associate with another at inappropriate times. On Sundays, let all occupy themselves in reading, except those who have been appointed to various duties. But if anyone should be so negligent and shiftless that she will not or cannot study or read, let her be given some work to do so that she will not be idle. Weak or sickly sisters should be assigned a task or craft of such a nature as to keep them from idleness and at the same time not to overburden them or drive them away with excessive toil. Their weakness must be taken into consideration by the Abbess.

Chapter 49: On the Observance of Lent

Although the life of a monk ought to have about it at all times the character of a Lenten observance, yet since few have the virtue for that, we therefore urge that during the actual days of Lent the brethren keep their lives most pure and at the same time wash away during these holy days all the negligences of other times. And this will be worthily done if we restrain ourselves from all vices and give ourselves up to prayer with tears, to reading, to compunction of heart and to abstinence. During these days, therefore, let us increase somewhat the usual burden of our service, as by private prayers and by abstinence in food and drink. Thus everyone of his own will may offer God "with joy of the Holy Spirit" (1 Thess. 1:6) something above the measure required of him. From his body, that is he may withhold some food, drink, sleep, talking and jesting; and with the joy of spiritual desire he may look forward to holy Easter. Let each one, however, suggest to his Abbot what it is that he wants to offer, and let it be done with his blessing and approval. For anything done without the permission of the spiritual father will be imputed to presumption and vainglory and will merit no reward. Therefore let everything be done with the Abbot's approval.

- Why is time during the season of Lent (roughly the 40 days leading up to Easter) so regimented?

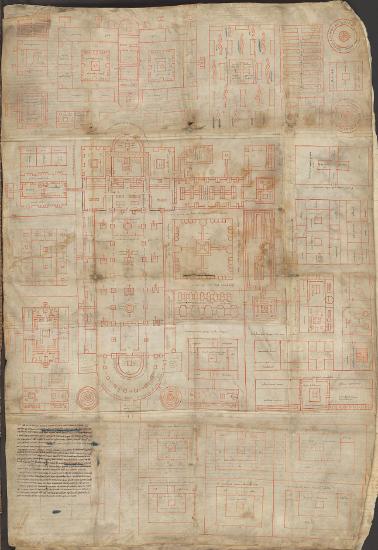

Chapter 66: On the Porters of the Monastery

At the gate of the monastery let there be placed a wise old woman, who knows how to receive and to give a message, and whose maturity will prevent her from straying about. This porter should have a room near the gate, so that those who come may always find someone at hand to attend to their business. And as soon as anyone knocks or a poor person hails her, let her answer "Thanks be to God" or "A blessing!" Then let her attend to them promptly, with all the meekness inspired by the fear of God and with the warmth of charity. Should the porter need help, let her have one of the younger sisters. If it can be done, the monastery should be so established that all the necessary things, such as water, mill, garden and various workshops, may be within the enclosure, so that there is no necessity for the sisters to go about outside of it, since that is not at all profitable for their souls. We desire that this Rule be read often in the community, so that none of the sisters may excuse herself on the ground of ignorance.

- What connections can we make between the importance of the porter's role and the opening chapters of the Rule?

Chapter 72: On the Good Zeal Which They Ought to Have

Just as there is an evil zeal of bitterness which separates from God and leads to hell, so there is a good zeal which separates from vices and leads to God and to life everlasting. This zeal, therefore, the sisters should practice with the most fervent love. Thus they should anticipate one another in honor (Rom. 12:10); most patiently endure one another's infirmities, whether of body or of character; vie in paying obedience one to another--no one following what she considers useful for herself, but rather what benefits another--; tender the charity of sisterhood chastely;

fear God in love; love their Abbess with a sincere and humble charity; prefer nothing whatever to Christ. And may He bring us all together to life everlasting!

Chapter 73: On the Fact That the Full Observance of Justice Is Not Established in This Rule

Now we have written this Rule in order that by its observance in monasteries we may show that we have attained some degree of virtue and the rudiments of the religious life. But for those who would hasten to the perfection of that life there are the teaching of the holy Fathers, the observance of which leads to the height of perfection. For what page or what utterance of the divinely inspired books of the Old and New Testaments is not a most unerring rule for human life? Or what book of the holy Catholic Fathers does not loudly proclaim how we may come by a straight course to our Creator? Then the Conferences and the Institutes and the Lives of the Fathers, as also the Rule of our holy Father Basil--what else are they but tools of virtue for right-living and obedient monks? But for us who are lazy and ill-living and negligent they are a source of shame and confusion. Whoever you are, therefore, who are hastening to the heavenly homeland, fulfill with the help of Christ this minimum Rule which we have written for beginners; and then at length under God's protection you will attain to the loftier heights of doctrine and virtue which we have mentioned above.

Footnotes

[1] This term is probably Copic (from Egypt) and roughly means "men of the company" (Venarde, Rule, 259).

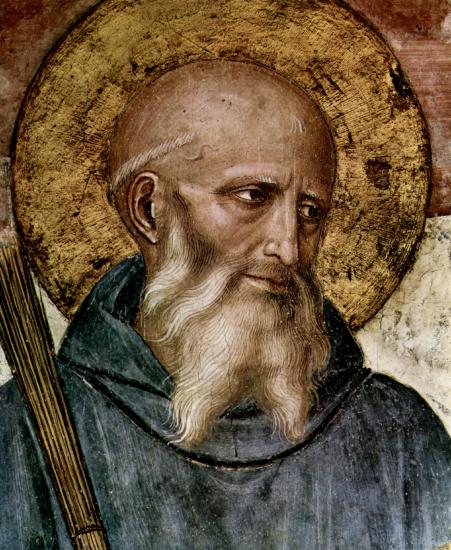

[2] A tonsure is a monastic haircut similar to that in Fig. 1 above meant to mimic Christ's crown of thorns. There are different varieties of monastic tonsures from the medieval period but the crown-shaped haircut has come to be seen as the classic type in art and even modern film.

[3] This is a mixture of Greek and Latin words for "circle" and "to wander"––that is, men who wander in circles (Venarde, Rule, 259).

[4] Stabilitas, or stability, is a chief concern of Benedict's and is the key to understanding both his introductory remarks and the spirit of the Rule itself.

[5] Some versions refer to an abbot in this section and other sections, others an abbot. An abbot is a male head administrator of a monastery, and an abbess is a female counterpart. This translation refers to the "abbess" as the head of a monastery and uses feminine pronouns to refer to monks.

[6] This statement is not very clear because it implies different bedding for different individuals.

[7] Here Benedict uses the Latin term crapula: "The word crapula meant drunkenness or a hangover in classical Latin" (Venarde, Rule, 263).

[8] There's no modern agreement on what this measurement would be.

[9] The Heptateuch refers to the first seven books of Hebrew Scripure: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, and Judges.