2.4: Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892)

- Page ID

- 102501

Although born in the Victorian era, Alfred, Lord Tennyson felt much affinity for the Romantic era. As with the Romantics, his first impulse was to think rather than do, and he relied more on emotional intelligence rather than rational judgment. These tendencies appear in the melancholy note of much of his early poetry, including “Oenone” (1829) and “Mariana” (1830). They may have been fostered by his painful childhood and early adulthood.

Tennyson was one of twelve children born to George Clayton Tennyson, a rector, and Elizabeth Fychte. A profoundly unhappy and emotionally unstable man, George Tennyson had been disinherited by his rich father. George took to drink, drugs, and abusive behavior, including one time threatening to kill Alfred’s older brother.

Tennyson escaped the strains of this home environment by attending Trinity College at Cambridge University. His extraordinary talent in writing poetry that incomparably matched sound and sense gave him ready entrée to The Apostles, an undergraduate society. Among that group was Arthur Henry Hallam who encouraged Tennyson’s literary  pursuits and who seemed to have helped him achieve a sense of self and identity independent from the ravages of his father’s mental instability. His need (and perhaps over-reliance) on Hallam’s help came to the fore upon Hallam’s unexpected, early death and Tennyson’s consequent writing of his great poem In Memoriam: To AHH. This poem marks both personal and general currents in Tennyson’s lifetime, for instance matching studies in geology with his own sense of despair. And it evinces his own propensity towards Romantic emotionalism and imagination, a propensity which he felt increasingly at odds with due to his era’s push towards outward action and realism.

pursuits and who seemed to have helped him achieve a sense of self and identity independent from the ravages of his father’s mental instability. His need (and perhaps over-reliance) on Hallam’s help came to the fore upon Hallam’s unexpected, early death and Tennyson’s consequent writing of his great poem In Memoriam: To AHH. This poem marks both personal and general currents in Tennyson’s lifetime, for instance matching studies in geology with his own sense of despair. And it evinces his own propensity towards Romantic emotionalism and imagination, a propensity which he felt increasingly at odds with due to his era’s push towards outward action and realism.

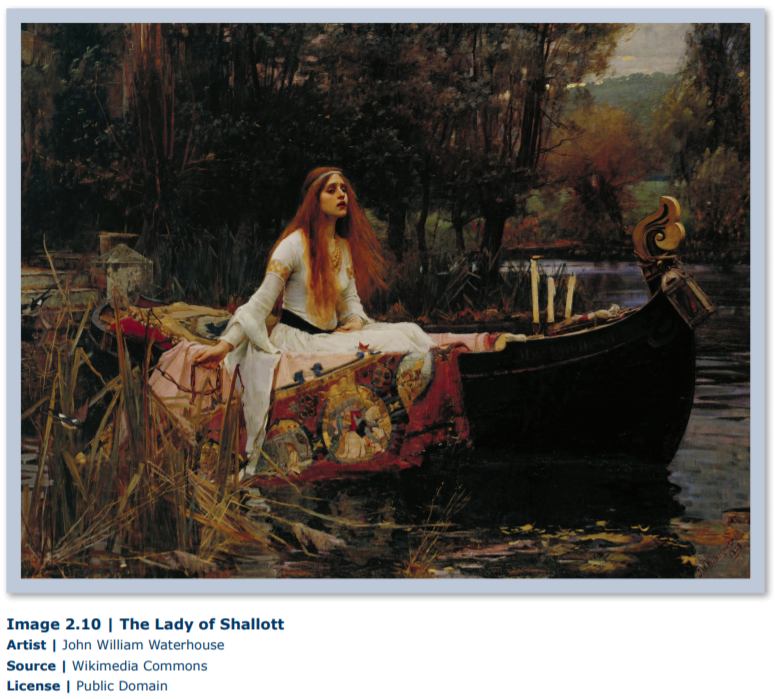

These tensions appear in “The Palace of Art” (1832), “The Lady of Shalott,” Maud (1855), and even “Ulysses.” In this poem, the protagonist wants to live life to the lees, yet foresees nothing but death before him. As his poems resonated with his readers, Tennyson’s fame grew. Upon the death of Wordsworth, Tennyson was named Poet Laureate (1850), confirming his place as one of England’s greatest poets. His Idylls of the King (1859) projected Victorian values onto Arthurian figures and fed into England’s great national myth of being the best of all worlds.

Tennyson’s personal life also had extremes of happiness and sorrow. After a prolonged engagement, Tennyson married Emily Selwood. Of their two children, the youngest, Lionel, died early of fever while returning from India. Tennyson was offered a peerage in 1884 and so became Alfred, Lord Tennyson. He died in 1892.

2.5.1: “The Lady of Shalott”

Part the First.

On either side the river lie

Long fields of barley and of rye,

That clothe the wold and meet the sky;

And thro’ the field the road runs by

To many-tower’d Camelot;

The yellow-leaved waterlily

The green-sheathed daffodilly

Tremble in the water chilly

Round about Shalott.

Willows whiten, aspens shiver.

The sunbeam showers break and quiver

In the stream that runneth ever

By the island in the river

Flowing down to Camelot.

Four gray walls, and four gray towers

Overlook a space of flowers,

And the silent isle imbowers

The Lady of Shalott.

Underneath the bearded barley,

The reaper, reaping late and early,

Hears her ever chanting cheerly,

Like an angel, singing clearly,

O’er the stream of Camelot.

Piling the sheaves in furrows airy,

Beneath the moon, the reaper weary

Listening whispers, ‘ ‘Tis the fairy,

Lady of Shalott.’

The little isle is all inrail’d

With a rose-fence, and overtrail’d

With roses: by the marge unhail’d

The shallop flitteth silken sail’d,

Skimming down to Camelot.

A pearl garland winds her head:

She leaneth on a velvet bed,

Full royally apparelled,

The Lady of Shalott.

Part the Second.

No time hath she to sport and play:

A charmed web she weaves alway.

A curse is on her, if she stay

Her weaving, either night or day,

To look down to Camelot.

She knows not what the curse may be;

Therefore she weaveth steadily,

Therefore no other care hath she,

The Lady of Shalott.

She lives with little joy or fear.

Over the water, running near,

The sheepbell tinkles in her ear.

Before her hangs a mirror clear,

Reflecting tower’d Camelot.

And as the mazy web she whirls,

She sees the surly village churls,

And the red cloaks of market girls

Pass onward from Shalott.

Sometimes a troop of damsels glad,

An abbot on an ambling pad,

Sometimes a curly shepherd lad,

Or long-hair’d page in crimson clad,

Goes by to tower’d Camelot:

And sometimes thro’ the mirror blue

The knights come riding two and two:

She hath no loyal knight and true,

The Lady of Shalott.

But in her web she still delights

To weave the mirror’s magic sights,

For often thro’ the silent nights

A funeral, with plumes and lights

And music, came from Camelot:

Or when the moon was overhead

Came two young lovers lately wed;

‘I am half sick of shadows,’ said

The Lady of Shalott.

Part the Third.

A bow-shot from her bower-eaves,

He rode between the barley-sheaves,

The sun came dazzling thro’ the leaves,

And flam’d upon the brazen greaves

Of bold Sir Lancelot.

A red-cross knight for ever kneel’d

To a lady in his shield,

That sparkled on the yellow field,

Beside remote Shalott.

The gemmy bridle glitter’d free,

Like to some branch of stars we see

Hung in the golden Galaxy.

The bridle bells rang merrily

As he rode down from Camelot:

And from his blazon’d baldric slung

A mighty silver bugle hung,

And as he rode his arm our rung,

Beside remote Shalott.

All in the blue unclouded weather

Thick-jewell’d shone the saddle-leather,

The helmet and the helmet-feather

Burn’d like one burning flame together,

As he rode down from Camelot.

As often thro’ the purple night,

Below the starry clusters bright,

Some bearded meteor, trailing light,

Moves over green Shalott.

His broad clear brow in sunlight glow’d;

On burnish’d hooves his war-horse trode;

From underneath his helmet flow’d

His coal-black curls as on he rode,

As he rode down from Camelot.

From the bank and from the river

He flash’d into the crystal mirror,

‘Tirra lirra, tirra lirra:’

Sang Sir Lancelot.

She left the web, she left the loom

She made three paces thro’ the room

She saw the water-flower bloom,

She saw the helmet and the plume,

She look’d down to Camelot.

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror crack’d from side to side;

‘The curse is come upon me,’ cried

The Lady of Shalott.

Part the Fourth.

In the stormy east-wind straining,

The pale yellow woods were waning,

The broad stream in his banks complaining,

Heavily the low sky raining

Over tower’d Camelot;

Outside the isle a shallow boat

Beneath a willow lay afloat,

Below the carven stern she wrote,

The Lady of Shalott.

A cloudwhite crown of pearl she dight,

All raimented in snowy white

That loosely flew (her zone in sight

Clasp’d with one blinding diamond bright)

Her wide eyes fix’d on Camelot,

Though the squally east-wind keenly

Blew, with folded arms serenely

By the water stood the queenly

Lady of Shalott.

With a steady stony glance—

Like some bold seer in a trance,

Beholding all his own mischance,

Mute, with a glassy countenance—

She look’d down to Camelot.

It was the closing of the day:

She loos’d the chain, and down she lay;

The broad stream bore her far away,

The Lady of Shalott.

As when to sailors while they roam,

By creeks and outfalls far from home,

Rising and dropping with the foam,

From dying swans wild warblings come,

Blown shoreward; so to Camelot

Still as the boathead wound along

The willowy hills and fields among,

They heard her chanting her deathsong,

The Lady of Shalott.

A longdrawn carol, mournful, holy,

She chanted loudly, chanted lowly,

Till her eyes were darken’d wholly,

And her smooth face sharpen’d slowly,

Turn’d to tower’d Camelot:

For ere she reach’d upon the tide

The first house by the water-side,

Singing in her song she died,

The Lady of Shalott.

Under tower and balcony,

By garden wall and gallery,

A pale, pale corpse she floated by,

Deadcold, between the houses high,

Dead into tower’d Camelot.

Knight and burgher, lord and dame,

To the planked wharfage came:

Below the stern they read her name,

The Lady of Shalott.

They cross’d themselves, their stars they blest,

Knight, minstrel, abbot, squire, and guest.

There lay a parchment on her breast,

That puzzled more than all the rest,

The wellfed wits at Camelot.

‘The web was woven curiously,

The charm is broken utterly,

Draw near and fear not,—this is I,

The Lady of Shalott.’

2.5.2: “The Lotos Eaters”

“Courage!” he said, and pointed toward the land,

“This mounting wave will roll us shoreward soon.”

In the afternoon they came unto a land

In which it seemèd always afternoon.

All round the coast the languid air did swoon,

Breathing like one that hath a weary dream.

Full-faced above the valley stood the moon;

And like a downward smoke, the slender stream

Along the cliff to fall and pause and fall did seem.

A land of streams! some, like a downward smoke,

Slow-dropping veils of thinnest lawn, did go;

And some thro’ wavering lights and shadows broke,

Rolling a slumbrous sheet of foam below.

They saw the gleaming river seaward flow

From the inner land: far off, three mountaintops,

Three silent pinnacles of agèd snow,

Stood sunset-flush’d: and, dew’d with showery drops,

Up-clomb the shadowy pine above the woven copse.

The charmèd sunset lingered low adown

In the red West: thro’ mountain clefts the dale

Was seen far inland, and the yellow down

Border’d with palm, and many a winding vale

And meadow, set with slender galingale;

A land where all things always seem’d the same!

And round about the keel with faces pale,

Dark faces pale against that rosy flame,

The mild-eyed melancholy Lotos-eaters came.

Branches they bore of that enchanted stem,

Laden with flower and fruit, whereof they gave

To each, but whoso did receive of them,

And taste, to him the gushing of the wave

Far, far away did seem to mourn and rave

On alien shores; and if his fellow spake,

His voice was thin, as voices from the grave;

And deep-asleep he seem’d, yet all awake,

And music in his ears his beating heart did make.

They sat them down upon the yellow sand,

Between the sun and moon upon the shore;

And sweet it was to dream of Fatherland,

Of child, and wife, and slave; but evermore

Most weary seem’d the sea, weary the oar,

Weary the wandering fields of barren foam.

Then some one said, “We will return no more;”

And all at once they sang, “Our island home

Is far beyond the wave we will no longer roam.”

2.5.3: “Ulysses”

It little profits that an idle king,

By this still hearth, among these barren crags,

Match’d with an aged wife, I mete and dole

Unequal laws unto a savage race,

That hoard, and sleep, and feed, and know not me.

I cannot rest from travel: I will drink

Life to the lees; all times I have enjoy’d

Greatly, have suffer’d greatly, both with those

That loved me, and alone; on shore, and when

Thro’ scudding drifts the rainy Hyades

Vext the dim sea: I am become a name;

For always roaming with a hungry heart

Much have I seen and known; cities of men

And manners, climates, councils, governments,

Myself not least, but honour’d of them all;

And drunk delight of battle with my peers,

Far on the ringing plains of windy Troy,

I am a part of all that I have met;

Yet all experience is an arch wherethro’

Gleams that untravell’d world, whose margin fades

For ever and for ever when I move.

How dull it is to pause, to make an end,

To rust unburnish’d, not to shine in use!

As tho’ to breathe were life. Life piled on life

Were all too little, and of one to me

Little remains: but every hour is saved

From that eternal silence, something more,

A bringer of new things; and vile it were

For some three suns to store and hoard myself,

And this gray spirit yearning in desire

To follow knowledge like a sinking star,

Beyond the utmost bound of human thought.

This is my son, mine own Telemachus,

To whom I leave the scepter and the isle—

Well-loved of me, discerning to fulfil

This labour, by slow prudence to make mild

A rugged people, and thro’ soft degrees

Subdue them to the useful and the good.

Most blameless is he, centred in the sphere

Of common duties, decent not to fail

In offices of tenderness, and pay

Meet adoration to my household gods,

When I am gone. He works his work, I mine.

There lies the port; the vessel puffs her sail:

There gloom the dark broad seas. My mariners,

Souls that have toil’d, and wrought, and thought with me—

That ever with a frolic welcome took

The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed

Free hearts, free foreheads—you and I are old;

Old age hath yet his honour and his toil;

Death closes all: but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods.

The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks:

The long day wanes: the slow moon climbs: the deep

Moans round with many voices. Come, my friends,

‘Tis not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

It may be that the gulfs will wash us down:

It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles,

And see the great Achilles, whom we knew.

Tho’ much is taken, much abides; and tho’

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven; that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

2.5.4: The Charge of the Light Brigade

1.

Half a league, half a league,

Half a league onward,

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

“Charge,” was the captain’s cry;

Their’s not to reason why,

Their’s not to make reply,

Their’s but to do and die,

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

2.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon in front of them

Volley’d and thunder’d;

Storm’d at with shot and shell,

Boldly they rode and well;

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of Hell,

Rode the six hundred.

3.

Flash’d all their sabres bare,

Flash’d all at once in air,

Sabring the gunners there,

Charging an army, while

All the world wonder’d:

Plunged in the battery-smoke

Fiercely the line they broke;

Strong was the sabre-stroke;

Making an army reel

Shaken and sunder’d.

Then they rode back, but not,

Not the six hundred.

4.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon behind them

Volley’d and thunder’d;

Storm’d at with shot and shell,

They that had struck so well

Rode thro’ the jaws of Death,

Half a league back again,

Up from the mouth of Hell,

All that was left of them,

Left of six hundred.

5.

Honour the brave and bold!

Long shall the tale be told,

Yea, when our babes are old—

How they rode onward.