2.3: Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861)

- Page ID

- 102500

Elizabeth Barrett Browning both epitomized the condition of women in the Victorian age and refuted it. Held under the “loving” hand of Edward Moulton Barrett, her Victorian patriarch of a father, Barrett Browning was confined to the private realm and the home to an extreme degree. At the age of fifteen, she suffered a spinal injury while saddling a pony. Seven years later a broken blood vessel in her chest left her weakened and suffering a chronic cough. An invalid, she was ultimately confined to her room. Despite these adversities, and with the encouragement and support of her father, Barrett Browning read widely, learned several languages, and published poetry and essays.

Her literary reputation grew to such an extent that she was suggested as a successor to Wordsworth as the Poet Laureate—a position that went to Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892). She communicated with the literary giants of her day, including Wordsworth, Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881), and Edgar Allen Poe (1809-1849). Her relationship with Robert Browning (1812-1889) began through his writing to her, expressing admiration for her poetry and love for her. His social visits turned quickly to a courtship that, when discovered by Edward Moulton Barrett, was adamantly opposed. Barrett Browning recorded the stress, uncertainty, and joy of this courtship in her Sonnets from the Portuguese (1850). She and Browning ultimately married in secret and sailed to Italy.

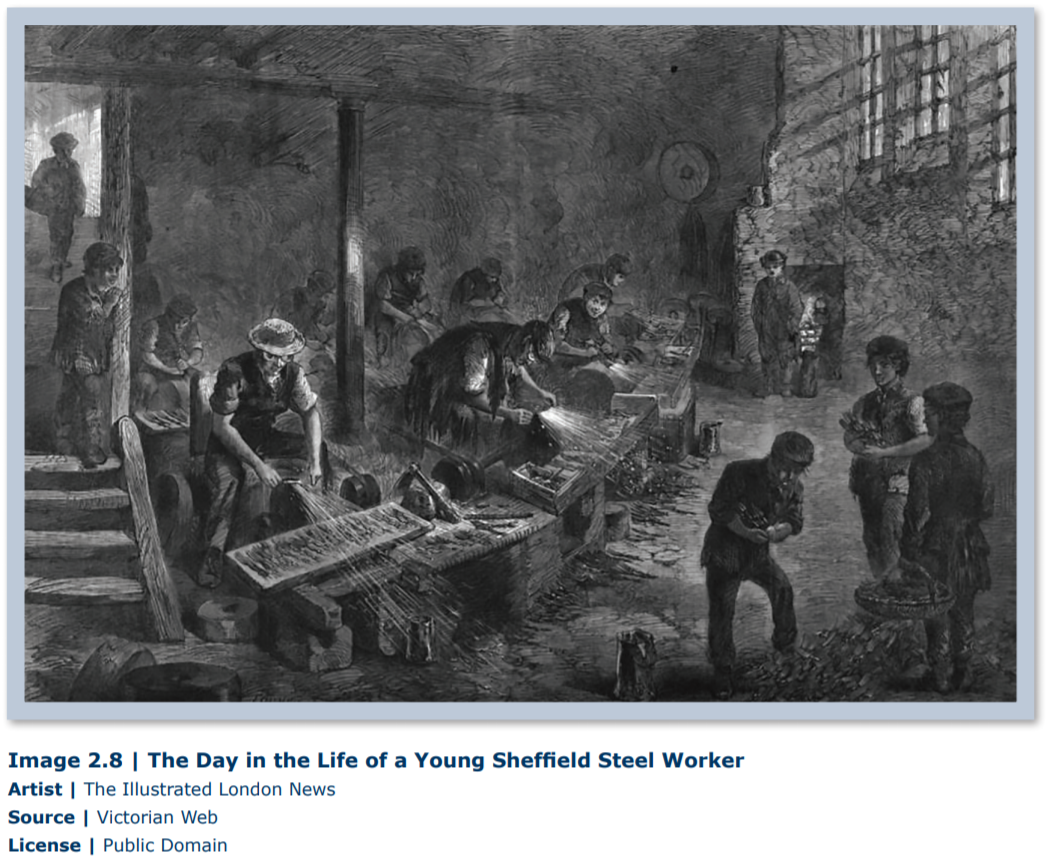

In Italy, Barrett Browning became involved in Italian Independence. Much of her work reflects her interest in individual—particularly women’s—rights, child labor, prostitution, abolition, and the plight of the poor and downtrodden. These interests combine in many of her greatest works, including Aurora Leigh (1856), a hybrid novel-poem that depicts the limitations placed upon women’s public and private ambitions. Its aesthetic devices rely upon woman-centric images and allusions. Her Sonnets from the Portuguese take on the most male-dominated of poetic forms asserting her place in this important tradition. In the most famous sonnet from this sequence, Sonnet 43, her highly personal expressions of love and passion—and ostensibly feminine emotionalism—are framed by the repetition of “I,” the poet herself.

In Italy, Barrett Browning became involved in Italian Independence. Much of her work reflects her interest in individual—particularly women’s—rights, child labor, prostitution, abolition, and the plight of the poor and downtrodden. These interests combine in many of her greatest works, including Aurora Leigh (1856), a hybrid novel-poem that depicts the limitations placed upon women’s public and private ambitions. Its aesthetic devices rely upon woman-centric images and allusions. Her Sonnets from the Portuguese take on the most male-dominated of poetic forms asserting her place in this important tradition. In the most famous sonnet from this sequence, Sonnet 43, her highly personal expressions of love and passion—and ostensibly feminine emotionalism—are framed by the repetition of “I,” the poet herself.

2.4.1: "The Cry of the Children"

“Pheu pheu, ti prosderkesthe m ommasin, tekna;”

[Alas, alas, why do you gaze at me with your eyes, my children.]—Medea.

Do ye hear the children weeping, O my brothers,

Ere the sorrow comes with years?

They are leaning their young heads against their mothers, —

And that cannot stop their tears.

The young lambs are bleating in the meadows;

The young birds are chirping in the nest;

The young fawns are playing with the shadows;

The young flowers are blowing toward the west —

But the young, young children, O my brothers,

They are weeping bitterly!

They are weeping in the playtime of the others,

In the country of the free.

Do you question the young children in the sorrow,

Why their tears are falling so?

The old man may weep for his to-morrow

Which is lost in Long Ago —

The old tree is leafless in the forest —

The old year is ending in the frost —

The old wound, if stricken, is the sorest —

The old hope is hardest to be lost:

But the young, young children, O my brothers,

Do you ask them why they stand

Weeping sore before the bosoms of their mothers,

In our happy Fatherland?

They look up with their pale and sunken faces,

And their looks are sad to see,

For the man’s grief abhorrent, draws and presses

Down the cheeks of infancy —

“Your old earth,” they say, “is very dreary;”

“Our young feet,” they say, “are very weak!”

Few paces have we taken, yet are weary —

Our grave-rest is very far to seek!

Ask the old why they weep, and not the children,

For the outside earth is cold —

And we young ones stand without, in our bewildering,

And the graves are for the old!”

“True,” say the children, “it may happen

That we die before our time!

Little Alice died last year her grave is shapen

Like a snowball, in the rime.

We looked into the pit prepared to take her —

Was no room for any work in the close clay:

From the sleep wherein she lieth none will wake her,

Crying, ‘Get up, little Alice! it is day.’

If you listen by that grave, in sun and shower,

With your ear down, little Alice never cries;

Could we see her face, be sure we should not know her,

For the smile has time for growing in her eyes, —

And merry go her moments, lulled and stilled in

The shroud, by the kirk-chime!

It is good when it happens,” say the children,

“That we die before our time!”

Alas, the wretched children! they are seeking

Death in life, as best to have!

They are binding up their hearts away from breaking,

With a cerement from the grave.

Go out, children, from the mine and from the city —

Sing out, children, as the little thrushes do —

Pluck you handfuls of the meadow-cowslips pretty

Laugh aloud, to feel your fingers let them through!

But they answer, “Are your cowslips of the meadows

Like our weeds anear the mine?

Leave us quiet in the dark of the coal-shadows,

From your pleasures fair and fine!

“For oh,” say the children, “we are weary,

And we cannot run or leap —

If we cared for any meadows, it were merely

To drop down in them and sleep.

Our knees tremble sorely in the stooping —

We fall upon our faces, trying to go;

And, underneath our heavy eyelids drooping,

The reddest flower would look as pale as snow.

For, all day, we drag our burden tiring,

Through the coal-dark, underground —

Or, all day, we drive the wheels of iron

In the factories, round and round.

“For all day, the wheels are droning, turning, —

Their wind comes in our faces, —

Till our hearts turn,— our heads, with pulses burning,

And the walls turn in their places

Turns the sky in the high window blank and reeling —

Turns the long light that droppeth down the wall, —

Turn the black flies that crawl along the ceiling —

All are turning, all the day, and we with all! —

And all day, the iron wheels are droning;

And sometimes we could pray,

‘O ye wheels,’ (breaking out in a mad moaning)

‘Stop ! be silent for to-day!’”

Ay! be silent! Let them hear each other breathing

For a moment, mouth to mouth —

Let them touch each other’s hands, in a fresh wreathing

Of their tender human youth!

Let them feel that this cold metallic motion

Is not all the life God fashions or reveals —

Let them prove their inward souls against the notion

That they live in you, or under you, O wheels! —

Still, all day, the iron wheels go onward,

As if Fate in each were stark;

And the children’s souls, which God is calling sunward,

Spin on blindly in the dark.

Now tell the poor young children, O my brothers,

To look up to Him and pray —

So the blessed One, who blesseth all the others,

Will bless them another day.

They answer, “Who is God that He should hear us,

While the rushing of the iron wheels is stirred?

When we sob aloud, the human creatures near us

Pass by, hearing not, or answer not a word!

And we hear not (for the wheels in their resounding)

Strangers speaking at the door:

Is it likely God, with angels singing round Him,

Hears our weeping any more?

“Two words, indeed, of praying we remember;

And at midnight’s hour of harm, —

‘Our Father,’ looking upward in the chamber,

We say softly for a charm.

We know no other words, except ‘Our Father,’

And we think that, in some pause of angels’ song,

God may pluck them with the silence sweet to gather,

And hold both within His right hand which is strong. ‘Our Father!’ If He heard us, He would surely (For they call Him good and mild) Answer, smiling down the steep world very purely, ‘Come and rest with me, my child.’

“But, no!” say the children, weeping faster,

“He is speechless as a stone;

And they tell us, of His image is the master

Who commands us to work on.

Go to! “ say the children,—” up in Heaven,

Dark, wheel-like, turning clouds are all we find!

Do not mock us; grief has made us unbelieving —

We look up for God, but tears have made us blind.”

Do ye hear the children weeping and disproving,

O my brothers, what ye preach?

For God’s possible is taught by His world’s loving —

And the children doubt of each.

And well may the children weep before you;

They are weary ere they run;

They have never seen the sunshine, nor the glory

Which is brighter than the sun:

They know the grief of man, without its wisdom;

They sink in the despair, without its calm —

Are slaves, without the liberty in Christdom, —

Are martyrs, by the pang without the palm, —

Are worn, as if with age, yet unretrievingly

No dear remembrance keep, —

Are orphans of the earthly love and heavenly:

Let them weep! let them weep!

They look up, with their pale and sunken faces,

And their look is dread to see,

For they think you see their angels in their places,

With eyes meant for Deity; —

“How long,” they say, “how long, O cruel nation,

Will you stand, to move the world, on a child’s heart, —

Stifle down with a mailed heel its palpitation,

And tread onward to your throne amid the mart?

Our blood splashes upward, O our tyrants,

And your purple shews your path;

But the child’s sob curseth deeper in the silence

Than the strong man in his wrath!”

2.4.2: “A Recognition”

True genius, but true woman! dost deny

The woman’s nature with a manly scorn,

And break away the gauds and armlets worn

By weaker women in captivity?

Ah, vain denial! that revolted cry

Is sobbed in by a woman’s voice forlorn,-

Thy woman’s hair, my sister, all unshorn

Floats back dishevelled strength in agony,

Disproving thy man’s name: and while before

The world thou burnest in a poet-fire,

We see thy woman-heart beat evermore

Through the large flame. Beat purer, heart, and higher,

Till God unsex thee on the heavenly shore

Where unincarnate spirits purely aspire!

2.4.3: Mother and Poet

I.

Dead! One of them shot by the sea in the east,

And one of them shot in the west by the sea.

Dead! both my boys! When you sit at the feast

And are wanting a great song for Italy free,

Let none look at me!

II.

Yet I was a poetess only last year,

And good at my art, for a woman, men said;

But this woman, this, who is agonized here, —

The east sea and west sea rhyme on in her head

For ever instead.

III.

What art can a woman be good at? Oh, vain!

What art is she good at, but hurting her breast

With the milk-teeth of babes, and a smile at the pain?

Ah boys, how you hurt! you were strong as you pressed,

And I proud, by that test.

IV.

What art’s for a woman? To hold on her knees

Both darlings! to feel all their arms round her throat,

Cling, strangle a little! to sew by degrees

And ‘broider the long-clothes and neat little coat ;

To dream and to doat.

V.

To teach them . . . It stings there! I made them indeed

Speak plain the word country. I taught them, no doubt,

That a country’s a thing men should die for at need.

I prated of liberty, rights, and about

The tyrant cast out.

VI.

And when their eyes flashed . . . O my beautiful eyes! . . .

I exulted; nay, let them go forth at the wheels

Of the guns, and denied not. But then the surprise

When one sits quite alone! Then one weeps, then one kneels!

God, how the house feels!

VII.

At first, happy news came, in gay letters moiled

With my kisses,—of camp-life and glory, and how

They both loved me; and, soon coming home to be spoiled

In return would fan off every fly from my brow

With their green laurel-bough.

VIII.

Then was triumph at Turin: Ancona was free!’

And some one came out of the cheers in the street,

With a face pale as stone, to say something to me.

My Guido was dead! I fell down at his feet,

While they cheered in the street.

IX.

I bore it; friends soothed me; my grief looked sublime

As the ransom of Italy. One boy remained

To be leant on and walked with, recalling the time

When the first grew immortal, while both of us strained

To the height he had gained.

X.

And letters still came, shorter, sadder, more strong,

Writ now but in one hand, I was not to faint, —

One loved me for two—would be with me ere long :

And Viva l’ Italia!—he died for, our saint,

Who forbids our complaint.”

XI.

My Nanni would add, he was safe, and aware

Of a presence that turned off the balls,—was imprest

It was Guido himself, who knew what I could bear,

And how ‘twas impossible, quite dispossessed,

To live on for the rest.”

XII.

On which, without pause, up the telegraph line

Swept smoothly the next news from Gaeta : — Shot.

Tell his mother. Ah, ah, his, ‘their ‘ mother,—not mine,’

No voice says “My mother” again to me. What!

You think Guido forgot

XIII.

Are souls straight so happy that, dizzy with Heaven,

They drop earth’s affections, conceive not of woe?

I think not. Themselves were too lately forgiven

Through THAT Love and Sorrow which reconciled so

The Above and Below.

XIV.

O Christ of the five wounds, who look’dst through the dark

To the face of Thy mother! consider, I pray,

How we common mothers stand desolate, mark,

Whose sons, not being Christs, die with eyes turned away,

And no last word to say!

XV.

Both boys dead? but that’s out of nature. We all

Have been patriots, yet each house must always keep one.

‘Twere imbecile, hewing out roads to a wall;

And, when Italy’s made, for what end is it done

If we have not a son?

XVI.

Ah, ah, ah! when Gaeta’s taken, what then?

When the fair wicked queen sits no more at her sport

Of the fire-balls of death crashing souls out of men?

When the guns of Cavalli with final retort

Have cut the game short?

XVII.

When Venice and Rome keep their new jubilee,

When your flag takes all heaven for its white, green, and red,

When you have your country from mountain to sea,

When King Victor has Italy’s crown on his head,

(And I have my Dead) —

XVIII.

What then? Do not mock me. Ah, ring your bells low,

And burn your lights faintly! My country is there,

Above the star pricked by the last peak of snow:

My Italy ‘s THERE, with my brave civic Pair,

To disfranchise despair!

XIX.

Forgive me. Some women bear children in strength,

And bite back the cry of their pain in self-scorn;

But the birth-pangs of nations will wring us at length

Into wail such as this—and we sit on forlorn

When the man-child is born.

XX.

Dead! One of them shot by the sea in the east,

And one of them shot in the west by the sea.

Both! both my boys! If in keeping the feast

You want a great song for your Italy free,

Let none look at me!