3: Equipment Through History

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

In efforts to keep their jobs, countless history teachers live by the words of George Santayana who is quoted saying, “Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” While it may seem like a trope, it is indeed important to keep in mind. But perhaps an even more important reason to study history is so that we can learn from it. How did our ancestors solve problems without computers? Is there a mechanical way to change scenes without a digital projector? Why do governments censor artists? History has answers to all these questions and more. It all starts with a good story.

8,000 BCE - Storytelling

We are all storytellers – and therefore actors in our own stories. Too often, our theatre industry separates itself into partisan categories that create two distinct groups, technicians and actors. When, in reality, we are all actors, and indeed all storytellers. You surely have embellished a story to a friend or lowered your voice to imitate the angry person at the store. That is acting, that is storytelling. So, it is fitting to start our review of theatre equipment and architecture at the very beginning, the telling of stories around the fire. As we learned in Chapter 1, the purpose of all theatre is quite simple: to tell a story.

It can be argued that theatre began in the very moment that humans began to tell stories to each other. We wanted to share our life experiences, struggles, and accomplishments. First, we had rituals. Bali had the Barong (Trance Dance) where farmers dressed in masks to act out the battle between good and evil. Mexico’s Día de Los Muertos is a ritual, as is Carnival and one can argue even the ubiquitous American Football Game. At some point in history, millennia ago, ritual transitioned into what we call theatre when storytelling began as a rehearsed tool used primarily to entertain an audience. Every culture cites a different time when that transition took place, in the Mayan culture they had professional entertainers (the talquetzque), the Chinese had professional Monk performers.

There are four basic elements required to create theatre. This was just as true millennia ago as it is today:

- An Idea

- A Space

- A Performer

- An Audience (with willingness to suspend disbelief)

Venue: Any place people can gather

2675 - 332 BCE – Egyptian Theatre

Over 4,000 years ago, the Egyptians created the first theatre that we have in written record. Theatre was a ceremonious ritual often used to conjure gods and resurrect the dead, regularly performed at festival times. The Egyptian coronation Festival Play is a commonly cited example where citizens celebrated annually the coronation of the pharaoh. Theatre grew from its roots at the fire and was performed in public areas, often at the steps of a temple to a large audience.

Venue: Public structures and temples

Greek (550 – 220BCE)

The Greeks of our distant history gave us a rich theatre foundation on which we built our modern theatre equipment and architecture. The Greeks were the first to use scenery and architecture to aid in storytelling. Most Greek theatres--which showed work from today’s “classic” playwrights Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes--were outdoor stages, often representing modern amphitheaters and arena stages. Greek amphitheaters were composed of a steeply raked seating area for the audience (the ‘auditorium’ or theatron) with a central performing area (the orchestra) in front of all the seats. Immediately behind the orchestra stage was the Greek’s chief stage invention, the Skene, a long wall with several doors or arches through which actors made their entrances.

To aid in the creation of space, the Greeks used many novel theatre devices. Periaktoi, were three-sided scenic columns on a central pivot that could be rotated to display three unique scenes. If a play required a dead body to be shown to the audience – as many did because Greek theatre traditions dictated that no violence be shown onstage – the Eccyclema (aka. Death Wagon) was used to roll people or scenery on stage. Another fascinating technical device was the mechane (machina in Latin). This led to the expression "Deus ex Machina," or God descending from a machine during the play. When a play called for a God to descend from the heavens or rise from earth, the Greeks employed this crake-like device to raise or lower actors and scenery from the stage up and over the skene.

Venue: Amphitheaters and arenas

New Technology: Skene, Periaktoi, Eccyclema, and Machnia

Roman (365BCE – 568CE)

With the fall of the Greek empire, Rome’s art and culture thrived. The new superpower of the region, Romans drew from Greece’s theatrical traditions to create new spectacles of space and technology. In the year 55BCE, Rome built the world’s first permanent theatre dedicated to theatre arts. Under Roman design, amphitheater auditoriums grew into larger, steeper cavas, and the skene expanded into the sometimes elaborately decorated three-story scaenae frons.

If you visit Rome today, you can tour the Colosseum, where is it known that elevators, moving platforms, and even the recreation of entire ship battles took place, further expanding upon the stagecraft of the Greeks. Interestingly, around 80CE, most actors were slaves. This is not hard to believe in the time of gladiators. Perhaps in reaction, as the Christian Church began to take hold in Rome, in the year 197, the ecclesiastical superiors forbade Christians to attend theatre; and in 468 the church banned spectacle entirely. These events show the power of theatre and story, as theatre was often more than just entertainment, it could be transformative or even revolutionary.

Venue: Amphitheaters and arenas

New Technology: Scaenae frons, Coliseum, Elevators, and Wagons

Medieval (400 – 1500)

With the fall of Rome, theatre – as Roman’s knew it – was effectively dead. Some traditions were kept alive by traveling performers who would journey from town to town, laying the groundwork for many medieval theatre practices.

Luckily, the same Church that banned all spectacle at the end of the Roman empire, can be credited with its revival. The ecclesiastical leadership found value in the storytelling to the masses that theatre delivered. Within Europe in the tenth century, clerics began to create staged scenes in the church. Eventually those scenes grew too big for the usual small-town church and sometime in the thirteenth century, they took their shows on the road – as they say. Acting companies funded by the church mounted platforms on top of wagons to create one of the first mobile stages. Known as Pageant Wagons (or the immobile Booth Stages), these ambulatory stages were pulled from town to town where the acting company could produce the same liturgical scenes that were once in the church, but to a much larger audience. The scenery was an oddly simplified version of the Greek skene, often being a small house known as a mansion, always the same and not changed from play to play – although one stage could have multiple mansions, just as the skene had multiple doors.

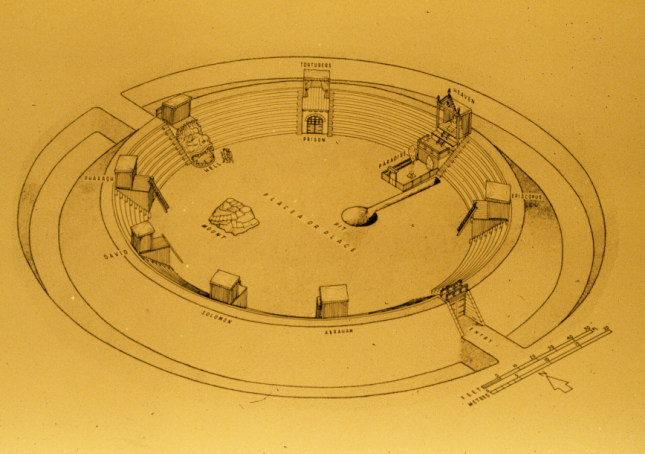

Another Medieval theatre tradition was the festival rounds. Produced every year, skilled craftspeople worked on the many scenes of the church (hell, the sermon on the mount, heaven, etc.). An arena-like stage was created with unique locations for each story. Audience members could traverse through the festival and experience every scene. We know there was complex scenery at this time as we have written record of the “secrets” artists employed, such as flying devices, pyrotechnics, and moving scenery. In one account, “One French Hellmouth was so elaborate that it required 17 men to operate its various pulleys, winches, and bellows.”[1]

Venue: Churches, rounds, and pageant wagons

New Technology: Secrets, mansions, pyrotechnics

Renaissance (1500 – 1675)

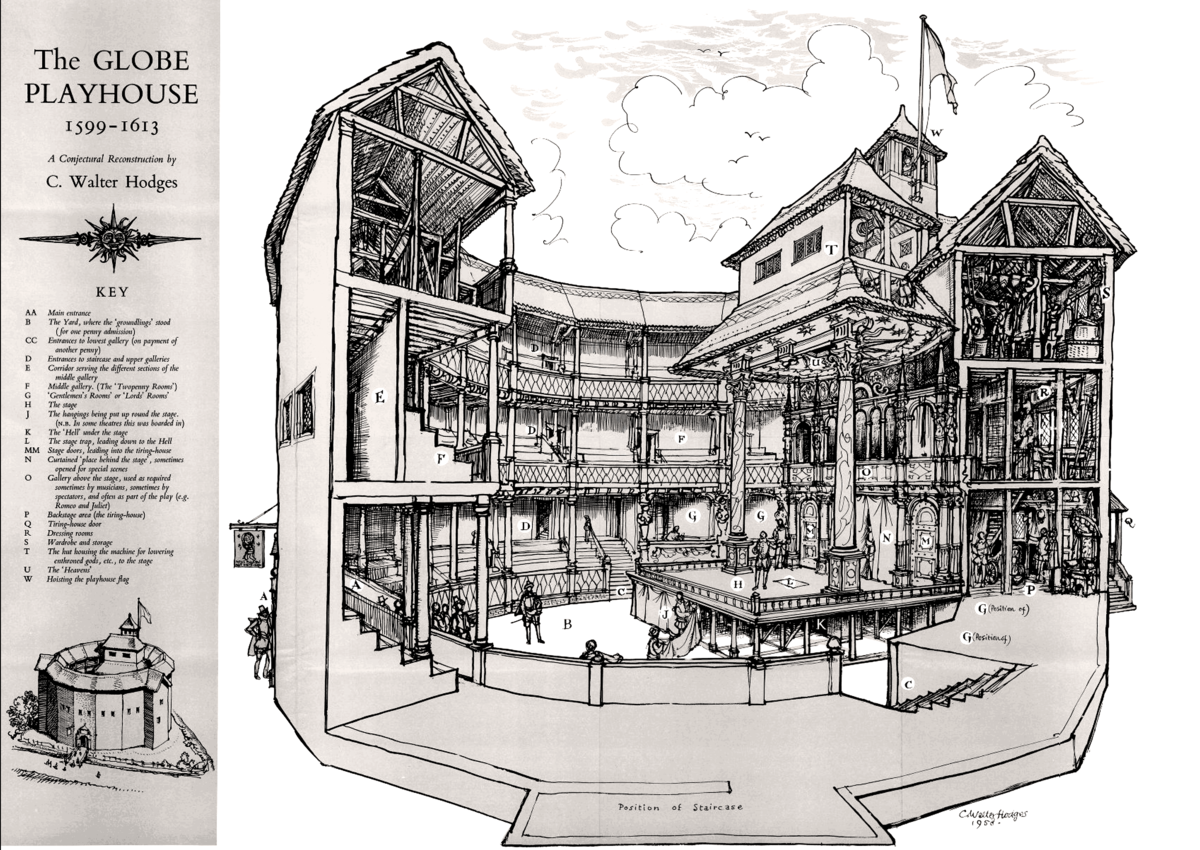

To the good fortune of many in Medieval Europe, art improved and theatre succeeded as a central part of modern culture, giving birth to the Renaissance. In 1576, the first public theatre was built in England, laying the groundwork for some of the most famous theatres of our time. William Shakespeare’s Globe theatre followed shortly after, opening in 1599. It was a venue that created space for citizens of all walks of life and financial means to enjoy theatre. The Globe Theatre is the most replicated theatre in the world, with over 24 replicas in operation today. The skene’s influence is still present as architects created playhouses with elaborate permanent backdrops. At the Teatro Olympico in Italy, the hallways of the skene were constructed with a forced perspective, a design style that creates the visual illusion that a hallway continues farther than it does in actuality – a sort of visual representation of today’s “fun houses”. In many renaissance theatres, the stages were slanted towards the audience to give them a better view, a technique known as the raked stage.

.jpeg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=350&height=262)

Even though little scenery was known to be constructed for the renaissance stage, artists did create backdrops and several props were understood to be used. Because some of the theatres were fully indoors, the renaissance gave birth to the first lighting for the stage in the way of candlelight. While this lighting was a great resource for designers, it also posed a great threat to the audience and performers. With hundreds of live flames burning throughout the evening, it was only a matter of time before the theatre burned down. Shakespeare’s own Globe Theatre burned down in 1613 due to a theatrical cannon misfire.

Venue: Permanent Theatres, Globe Theatre

New Technology: Candlelight, show-specific backdrops, forced perspective, raked stages

Restoration+ (1660 – 1700)

At the end of the Renaissance, public theatres closed their door again. This time due to a ban from the Puritans in 1642 in who recently seized power over England and reigned for 18 years. With the fall of the Puritans, King Charles II reopened the public theatres to rein in a fruitful 40 years of restorative theatrical innovation.

Theatre innovated in other parts of Europe and Russia over this time and those influences spread over Europe and England. The principal theatre at the time is the proscenium theatre. Now designers have offstage space, in the wings and behind the scenery. Set designers were still creating backdrops and other decorative scenery, but most of it was purely visual – as opposed to our more modern standards of building entire working houses on stage. Nevertheless, the stage was a visual treat, now framed with borders and legs to limit the audience’s view of the offstage area.

Venue: Permanent Proscenium Theatres

New Technology: Wings, borders, legs

Japan and Kabuki Theatre (1607 - 1867)

Meanwhile, to the east of Europe, Japan was expanding its own theatrical spectacle. At the time, the traditional theatre of Japan, the Noh (Nō) Theatre, had strong roots dating as far back as 1350. As Japan’s desire for an avant-garde theatre with more spectacle grew, kabuki emerged. Often a 12-hour-long event full of dance and music, audiences could come and go as they pleased, and the actors often entered and exited through the audience area further involving the audience in the event.

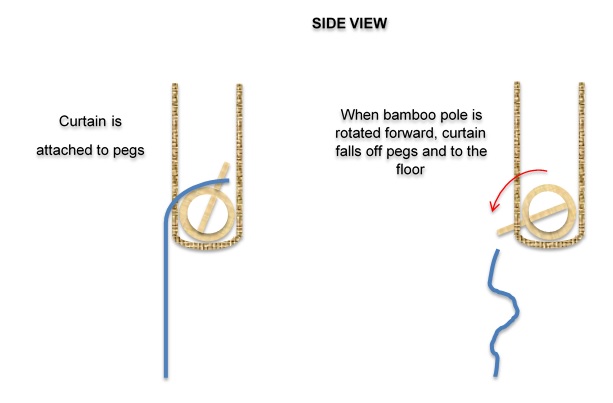

Kabuki theatre designers crafted many theatre machines and devices that we still use today. Most Kabuki stages had multiple elevator traps, revolving stages (even concentric revolving stages), a western-style proscenium, and flying effects known as chunori. Japanese theatres were very advanced at the time, often hosting “water plays” (mizumono) which had their own special water effects (honmizu) throughout. But perhaps one of the biggest theatrical devices that Kabuki theatre is known for today is the Kabuki Drop (originally Furiotoshi (shake)). Japanese artisans and engineers invented the Kabuki Drop to facilitate quick set changes. It is a device used to quickly drop a fabric backdrop from its hanging position in the theatre. A simple bamboo pole with small prongs on it pointing up would hold a curtain in the air. At the right moment, stagehands would pull a rope, rotating the pole and pointing the prongs down, thus quickly dropping the curtain.

Venue: Permanent Proscenium Theatres

New Technology: elevator traps, revolving stages, flying effects, water effects, Kabuki Drop

The Industrial Revolution+ (1760 – 1900)

Leading into the industrial Revolution, American theatre was just getting started. The first theatre in America was built in Williamsburg, Virginia in 1716, providing a permanent space for theatre in the new colonies. Yet somehow, we see history repeating itself again. In the beginning of the industrial revolution, after America declared their independence, all stage performances were banned in 1774 for over ten years – assumedly, to control public opinion. Theatre clearly continued to have power over thought and story.

Nevertheless, over the brief 80 years that were the industrial revolution, theatre saw some of its biggest technical growth. Theatre technology usually follows the technology of the time; the Industrial Revolution was no different as it was ripe with technological advancement. In 1792, theatrical lighting got another important lighting upgrade with the advent of Gas Lighting. Now, theatre technicians could change the intensity of the light on stage. We saw partial blackouts and the ability to focus the audience’s attention with light. Designers experimented with colored glass and liquids in front of the flame to change the color of the gaslight to further effect the mood of the stories on stage.

Not to be outdone, less than 100 years after the gas light, Thomas Edison invented the light bulb which quickly spread to theatres all over the world, providing electric light to millions. The first theatre was lit with electricity in 1881 and all others quickly followed or were left behind. Theatres now had complete blackouts, granular intensity changes, and (perhaps more importantly) fewer fires.

Venue: Permanent Proscenium Theatres

New Technology: Gas Lighting, Electric Lighting, blackouts, intensity changes, colored lights

The 20th Century

Much of what we know of modern theatre took its hold in the twentieth century. Playwrights began writing plays of realism, an art that more deeply reflected life, and stagecraft had to follow in this storytelling practice. Splintering from other twentieth century theatre movements, artist began to experiment with “found spaces”, further challenging the lines of the actor/audience relationship. Perhaps from this movement grew the desire for more black boxes, arena, and thrust stages to better involve the audience’s participation in the story. Artists everywhere were implementing every technology available to better tell their stories. The twentieth century even saw the first theatrical degree program at a university.

It is hard to imagine a production today without the use of recorded music or sound effects, but its introduction to theatre is surprisingly recent. While we had sound in theatre since the advent of live music millennia ago, it was not until the 1930s that audio playback was first used on stage with the arrival of record players and amplified speakers. Throughout the twentieth century, sound technology advanced from record players to different versions of cassette tapes. This form of manual analogue sound playback was used regularly, all the way up until the 1980s with the invention of computers capable of digital playback.

Photo by Jace & Afsoon on Unsplash

Also, with the invention of the computer, lighting systems began to see an upgrade. Now designers were able to store preset scenes on a digital computer, switching from scene to scene with the press of a button. With this new control, companies began to create moving lights that could respond to the commands of a computer, move to predefined locations, and change colors. At the time, this seemed like pure magic, opening endless possibilities for lighting designers.

Venue: Venue: Permanent Theatres (Arena, trust, blackbox, and proscenium), found spaces

New Technology: Computer Control, electronic sound playback, digital computers, moving lights

The 21st Century

Technology is advancing quickly. So far, Moore’s law has been holding true. Moore hypothesized that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit will double about every two years. Simply speaking, digital storage and computer capacity is growing at an exponential rate. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, lighting systems could hold around 1.44MB of data, twenty years later that ever-growing number exceeds 71,000% of the size it once was. With this advance in technology, technicians have created state-of-the art tools used in theatre storytelling.

Entire shows can be designed virtually in full 3D with every detail expertly rendered, including scenery, lighting, sound, and video. Before a single paint can is opened, artists can ensure everything fits together and that all colors match a director’s vision. This information can be transferred among computers limiting the need for many human operators. Some productions even run on a word-clock, sending time-based commands to every theatre system (lights, sound, video, automation), automatically triggering each system without the need for human input.

For better or worse, the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020/2021, saw a shift of venue. People were unable to be together in the same room as audience and performer are accustomed to. So, a quick shift to a digital venue took place, the dreaded “Zoom Room” (or any other number of video chat platforms). Actors were able to perform their plays to a virtual audience, many hailing from all over the world simultaneously. Of course, when it became safe to return in person again, most artists quickly dismissed the Zoom Room as a venue, mainly because it lacked intimacy and produced a forced relationship between the actor and the audience. But who knows, sometime in this century we may see video chat technology advance to a more palatable level, leaving the traditional theatre venues behind.

The early twenty-first century saw the adoption of computer-controlled digital video projectors capable of painting the set walls with full-color moving video. Many theatre companies are embracing this technology, reducing their need for multiple backdrops or scene changes. We are even beginning to see holographic projection take the stage. With the invention of artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning algorithms, artists can create holographic projections of anything, even long-deceased actors and musicians. Now we even have applications like OpenAI’s Dall-E that can generate any image with a simple word prompt.

The future of the twenty-first century is exciting, and a little scary. Where technology will take our art form is yet to be seen, but if history has anything to tell us, it will remain powerful, transformative, and state-of-the-art.

Venue: Permanent Theatres, digital video rooms

New Technology: Digitized automation, Holograms, Artificial intelligence (AI)

[1] Greenwald, Mike, et al. The Longman Anthology of Drama and Theater: A Global Perspective. Longman, 2004. p. 413

Greenwald, Mike, et al. The Longman Anthology of Drama and Theater: A Global Perspective. Longman, 2004. p. 413

Ogawa, Toshiro. Theatre Engineering and Stage Machinery. Revised 2010. Entertainment Technology Press, 2010.