12.5: The many forms of iconoclasm

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 147872

Erased from memory: the Severan Tondo

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): A conversation with Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris in front of The Severan Tondo, c. 200 C.E., 30.5 cm, tempera on wood (Altes Museum, Staatliche Museen, Berlin)

Additional resources:

Klaus Forschen, The portraits of Roman emperors and their families,” in The Emperor and Rome: Space, Representation, and Ritual, edited by Björn C. Ewald and Carlos F. Noreña (Cambridge University Press, 2010)

Eric R. Varner, Mutilation and Transformation : Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture (Brill 2004)

Rewriting history: damnatio memoriae in ancient Rome

If the Roman government condemned a ruler, his portraits often died with him.

We know that Roman emperors were often raised to the status of gods after their deaths. However, just as many were given the opposite treatment—officially erased from memory.

Condemning memory

Damnatio memoriae is a term we use to describe a Roman phenomenon in which the government condemned the memory of a person who was seen as a tyrant, traitor, or other sort of enemy to the state. The images of such condemned figures would be destroyed, their names erased from inscriptions, and if the doomed person were an emperor or other government official, even his laws could be rescinded. Coins bearing the image of an emperor who had his memory damned would be recalled or cancelled. In some cases, the residence of the condemned could be razed or otherwise destroyed. [1]

This was more than a form of casual, politically-motivated vandalism, carried out by disgruntled individuals, since the condemnation required approval of the Senate and the effects of the official denunciation could be seen far from Rome. There are many examples of damnatio memoriae throughout the history of the Roman Republic and Empire. As many as 26 emperors through the reign of Constantine had their memories condemned; conversely, about 25 emperors were deified after their deaths. The damning of memory phenomenon, however, is not unique to the Roman world. Egyptian pharaohs Hatshepsut and Akhenaten likewise had many of their their images, monuments, and inscriptions destroyed by political opponents or religious purists. [2]

Did it work?

Instances of damnatio memoriae were not always completely successful in wiping out the memory of an individual. Among the emperors who suffered damnatio memoriae are some of the best-known figures from Roman history, including Gaius (a.k.a. Caligula) and Nero. The notoriety of these men comes to us not only from texts written during their lifetimes and later, but also from images which survived the immediate violence of the damnatio memoriae and then centuries of neglect.

For instance, one marble portrait preserves not only the image of Caligula, but also traces of paint, informing us of the existence of this condemned emperor as well as the polychromy of ancient sculpture. In antiquity, these types of images were considered very powerful and closely linked with the identity of the person they represented.

Small heads, big reputations

Caligula was the first emperor to have his images purposefully destroyed after his death. It is impossible to know how many portraits in bronze or other precious metals were melted down, but a number of marble portraits show traces of being re-cut or simply dismantled and disposed of. Workshop procedures for official imperial portraits dictated that many full-length statues in stone were to be created in two pieces. So heads of Caligula, like those now in the Getty Villa and the Yale University Art Gallery (above), could be fairly easily detached from the bodies and tossed aside and a portrait head of the new emperor would swiftly replace the offending one.

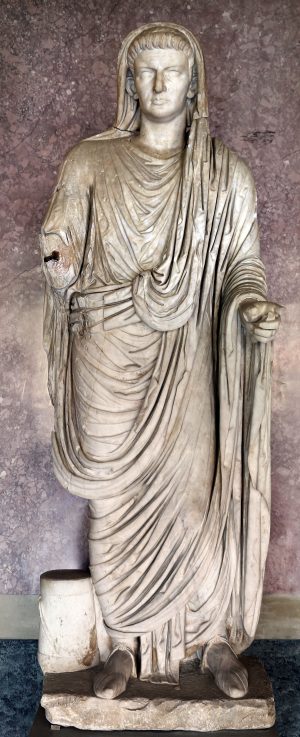

A full-length, one-piece statue of a pontifex maximus (chief state priest, a title held by the emperor) from Velleia, however, apparently underwent a kind of sculptural recycling. The face of Caligula’s successor Claudius appears rather small in comparison to the head and the rest of the body—suggesting to some scholars that it was cut down from a portrait of Caligula.

Cancelleria Reliefs: Nerva replaces Domitian

A similar re-cutting is evident on a set of reliefs found in Rome and now housed in the Vatican Museums (below). The so-called Cancelleria Reliefs show mythological and allegorical figures celebrating members of the Flavian dynasty for their military successes.

In one, Domitian departs from Rome on a military campaign, ushered out of the city by Victoria, Mars, and Minerva, as well as personifications of the Senate and the Roman people. Yet the head atop the stately tunic-clad body of the emperor is not that of Domitian. Instead it is Nerva, who succeeded Domitian after his assassination and subsequent damnatio memoriae. As in the Claudius pontifex maximus statue from Velleia, Nerva’s face is far too small for the relief and even appears comical when compared to the divinities surrounding him.[3] Apparently the sculpture was recarved.

Slightly more elegant solutions for damnatio memoriae could be executed in metal statuary. The face of a bronze equestrian portrait of Domitian (below) was sawed off and replaced with that of his successor, Nerva. The result is much less jarring than on the Cancelleria relief, as the bronze “mask” was made to the same scale as the rest of the statue and the join is mostly unnoticeable.

Caracalla removes the image of Geta

Perhaps the most striking and widespread examples of damnatio memoriae come from the reign of Caracalla, a member of the Severan Dynasty who ruled from 211-217 C.E. He was initially co-emperor with his younger brother Geta, but after months of squabbling between the sibling rulers, Caracalla had Geta assassinated. This death was quickly followed by a damnatio memoriae, one in which it became a capital offense to even speak the name of the younger co-emperor.

In Rome, Geta’s image was eliminated from reliefs on the Arch of the Argentarii. No attempt at an elegant recarving was made as in the Cancelleria Reliefs; in a panel showing Septimius Severus and Julia Domna (the parents of Caracalla and Geta) sacrificing at an altar, a caduceus floats over an empty space where Geta must have stood.[4] Even images of Geta’s wife and father-in-law were carved out of the Arch of the Argentarii panels, as they too had suffered a damnatio memoriae. The names of all the condemned individuals were erased from the arch and replaced with new inscriptions honoring Caracalla.

Erasing memory across time and space

A painted panel found in Egypt demonstrates the very long reach of Roman vengeance when enacting a damnatio memoriae. The panel shows the Severan family: Julia Domna wears heavy pearl earrings and necklaces; Septimius’s hair and beard are tinged with gray; and highlights in the eyes of all the figures add a lifelike quality. Caracalla’s boyish face—painted when he was merely heir to the throne—peers out to the viewer’s left. Next to him is a circular erasure in the paint where Geta once appeared. This deletion is dramatic when considering the procedures of damnatio memoriae. Someone in the province of Egypt, far from the center of the Empire, was charged with erasing the image of a child—a child who grew up to be co-emperor, only to be killed by his own brother. The tyranny of Caracalla and the thoroughness of damnatio memoriae meant that practically no image of the emperor’s enemies, no matter how small or out-of-date, would escape destruction.

Damnatio memoriae continued in the Roman world through the fourth century C.E., as seen in disfigured portraits of Constantine’s rival Maxentius. With Christianity made official in the Roman world, vandalism of imperial portraits continued, but with more of a religious bent than a political one. The fact that Roman portraits were removed, damaged, or destroyed because of dramatic changes in the subjects’ reputations is unmistakable evidence that such images are more than just “pictures.” A portrait can carry meaning over decades and centuries—whether it is of a Roman emperor, a Communist leader like Joseph Stalin, a dictator like Saddam Hussein, or Confederate generals in the United States.

Notes:

- Nero’s Domus Aurea (Golden House) in downtown Rome was eventually filled in and built over by his successors in the Flavian Dynasty, but it was not a systematic destruction. In fact, there is evidence Vespasian lived in the controversial villa before he and his sons turned the land from Nero’s private estate back over to the public.

- Hatshepsut’s successor, Thutmose III, ordered her images, cartouches, and monuments destroyed as she was seen as a usurper to his throne. Akhenaten, who brought monotheism briefly to Egypt, suffered a sort of damnatio memoriae by those who enthusiastically returned to polytheism after his death.

- In a coup de grâce for the Cancelleria Reliefs, they seem to have never been displayed, instead discarded in a Republican-period cemetery after Nerva died just fifteen months into his reign. The Flavian Dynasty was over and it would have been too challenging to re-recarve the portrait of Nerva into Trajan.

- It appears that Julia Domna’s left arm was carved in the space where Geta’s body once was; in the original format, she was probably holding the caduceus.

Additional Resources:

Sarah Bond, “Erasing the Face of History,” The New York Times, May 14, 2011

S. Bundrick and E. Varner, From Caligula to Constantine: Tyranny & Transformation in Roman Portraiture (Michael C. Carlos Museum, 2001).

Harriet I. Flower, The Art of Forgetting: Disgrace & Oblivion in Roman Political Culture (University of North Carolina Press, 2006).

Eric Varner, Mutilation and Transformation: Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture (E.J. Brill, 2004).

Making and Mutilating Manuscripts of the Shahnama

Illustrated manuscripts are one of the glories of Persian art, especially those made during the heyday of production from the fourteenth century to the sixteenth century. The most popular text was the Shahnama, or Book of Kings. This 50,000-couplet poem recounts the history of Iran from the creation of the world to the coming of the Arabs in the seventh century through the reigns of fifty successive monarchs. Rulers and their courtiers often commissioned splendid copies of the Shahnama to link themselves to the heroes of the past, whether the “Alexander of the Age” or “The Lord of the World.”

Today some of the most important manuscripts are sadly dismembered. Reconstructing the history of two of these splendid manuscripts—from creation to mutilation—shows how they have been used (and misused) over the centuries as political propaganda, loot, and even fodder in the international art market.

The Great Mongol Shahnama and the Tahmasp Shahnama

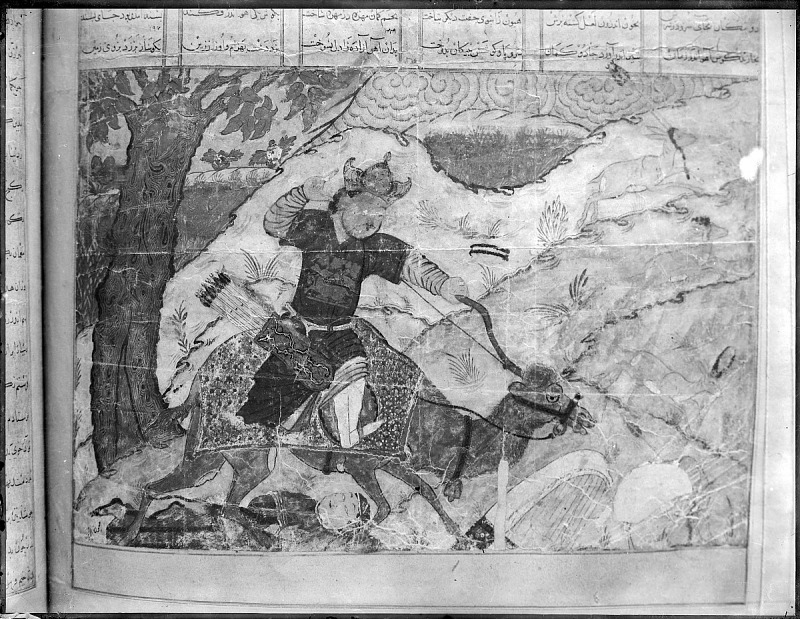

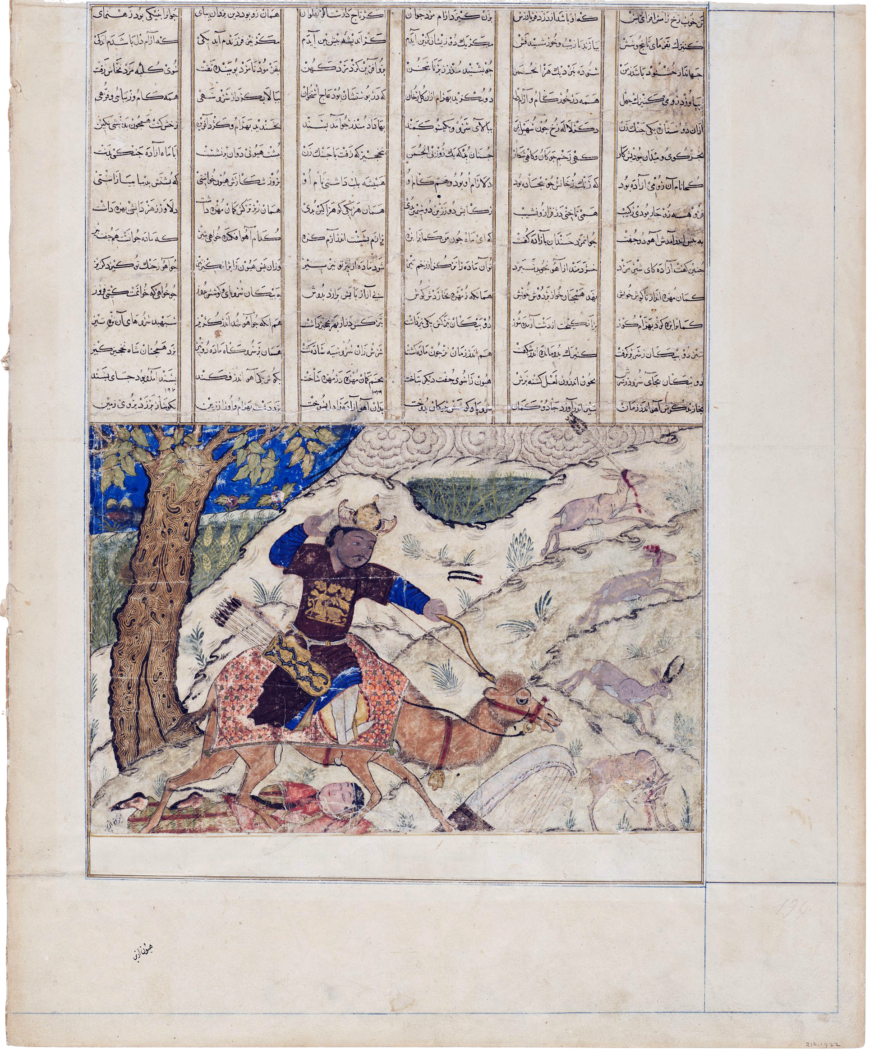

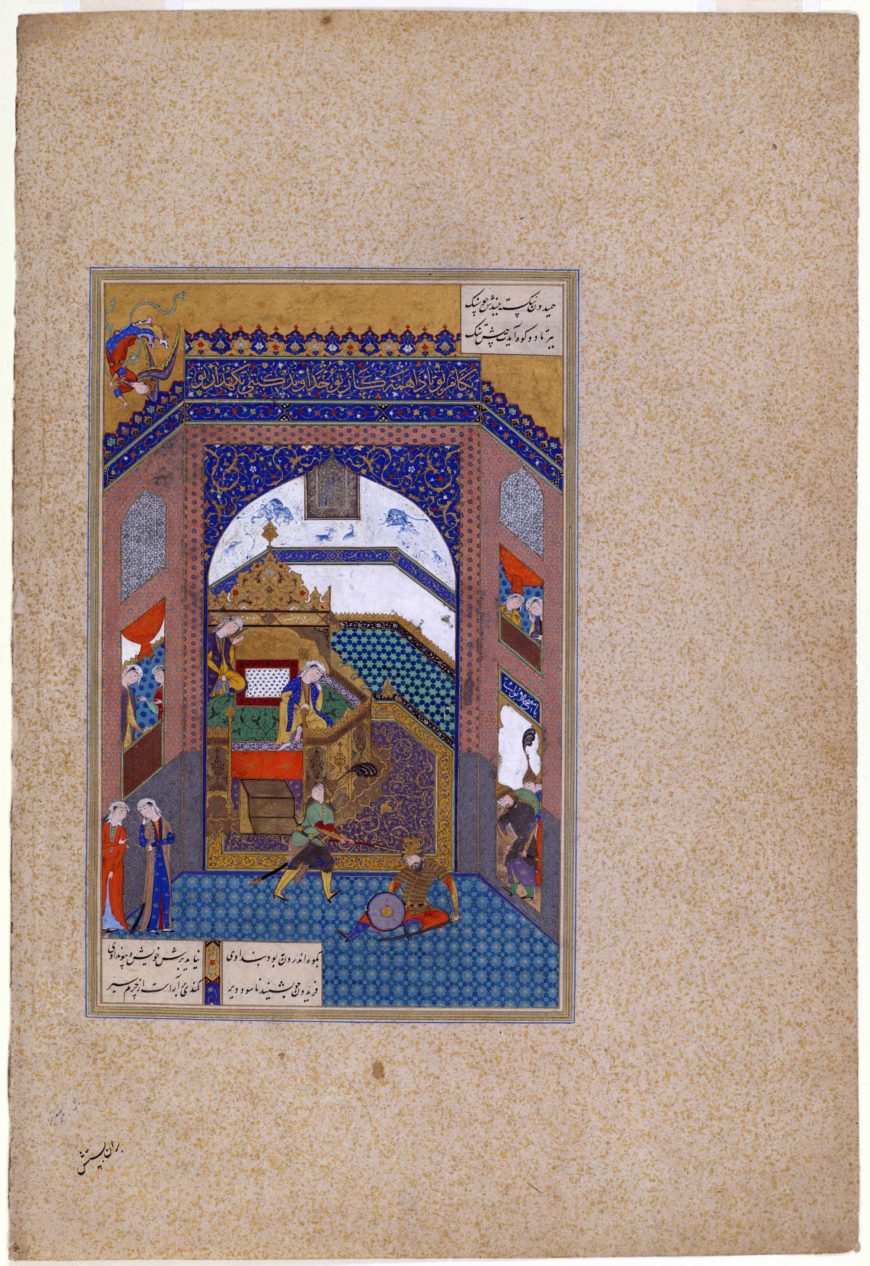

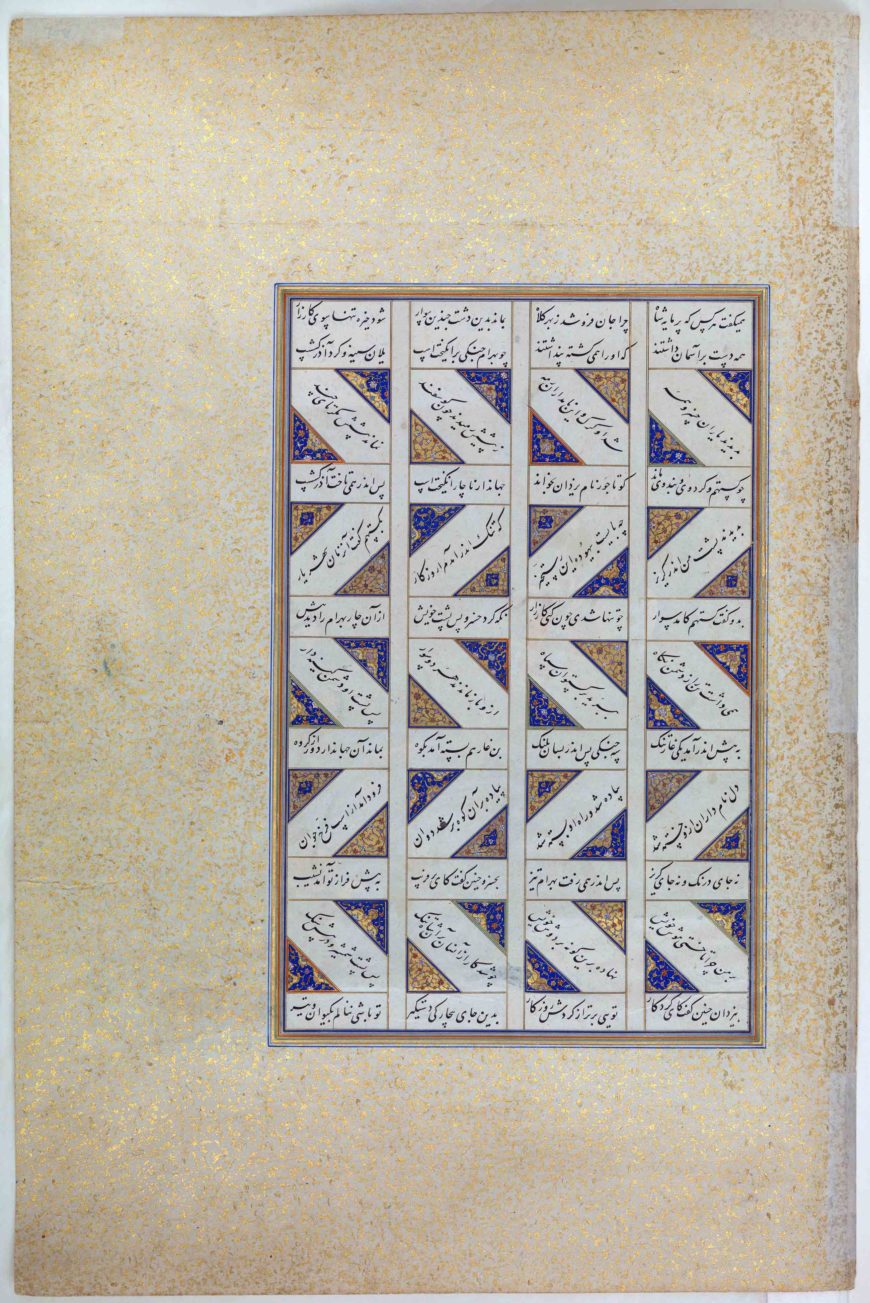

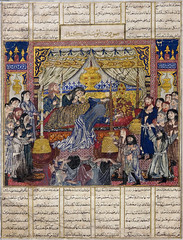

These two illustrated pages (above) come from the most ambitious manuscripts known: the Great Mongol Shahnama, made for the Mongol court in northwest Iran around 1330, and the Tahmasp Shahnama, made two centuries later in the same region for the Safavid shah Tahmasp (and perhaps inspired by the earlier one).

Large books with hundreds of illustrations

Both of these manuscripts are very large books. The 759 folios, or leaves, in the Tahmasp Shahnama measure 32 x 47 cm (12½ x 18 ½ inches) with a whopping 258 illustrations, many of them nearly full size and sometimes spilling into the gold-sprinkled margins. The Great Mongol Shahnama was even larger: it had around 300 folios with some 200 illustrations, most about half or two-thirds the area of the written surface.[1] Both projects must have taken a decade to complete, even with a workshop of papermakers, calligraphers, painters, illuminators, binders, and other craftsmen.

Both manuscripts became part of the royal library, a necessary accoutrement of a cultured prince from the fourteenth century onwards in Persia and elsewhere. The Great Mongol Shahnama seems to have stayed there until the nineteenth century when the manuscript, perhaps unfinished or damaged, was repaired: some of the faces in the paintings were retouched with pink cheeks and heavy eyebrows typical of the nineteenth-century Qajar style, the folios were numbered and remargined on imported Russian paper dated 1832, and the original two volumes were conflated into one. A photograph taken in Tehran at the end of the nineteenth century by the Armenian photographer Antoine Sevruguin shows the bound volume open to one of the illustrated pages.

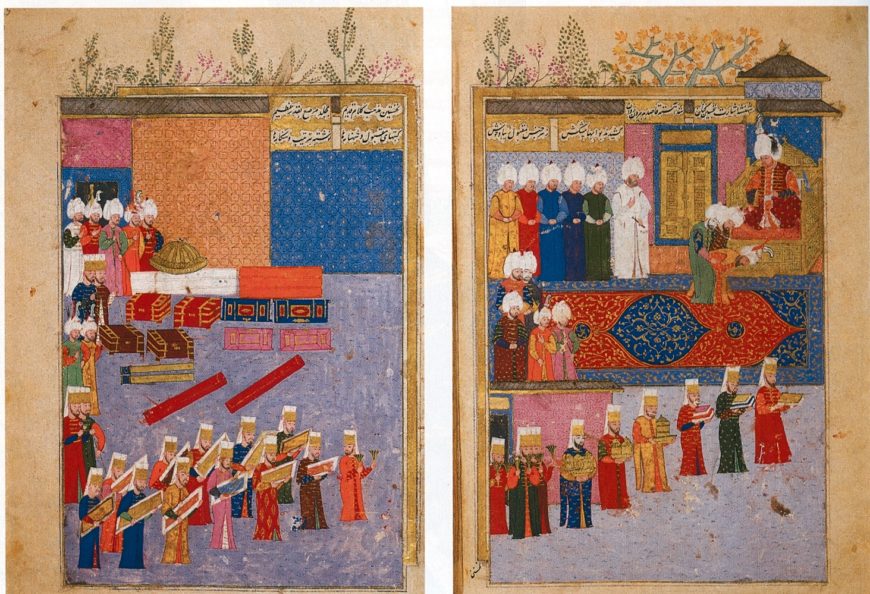

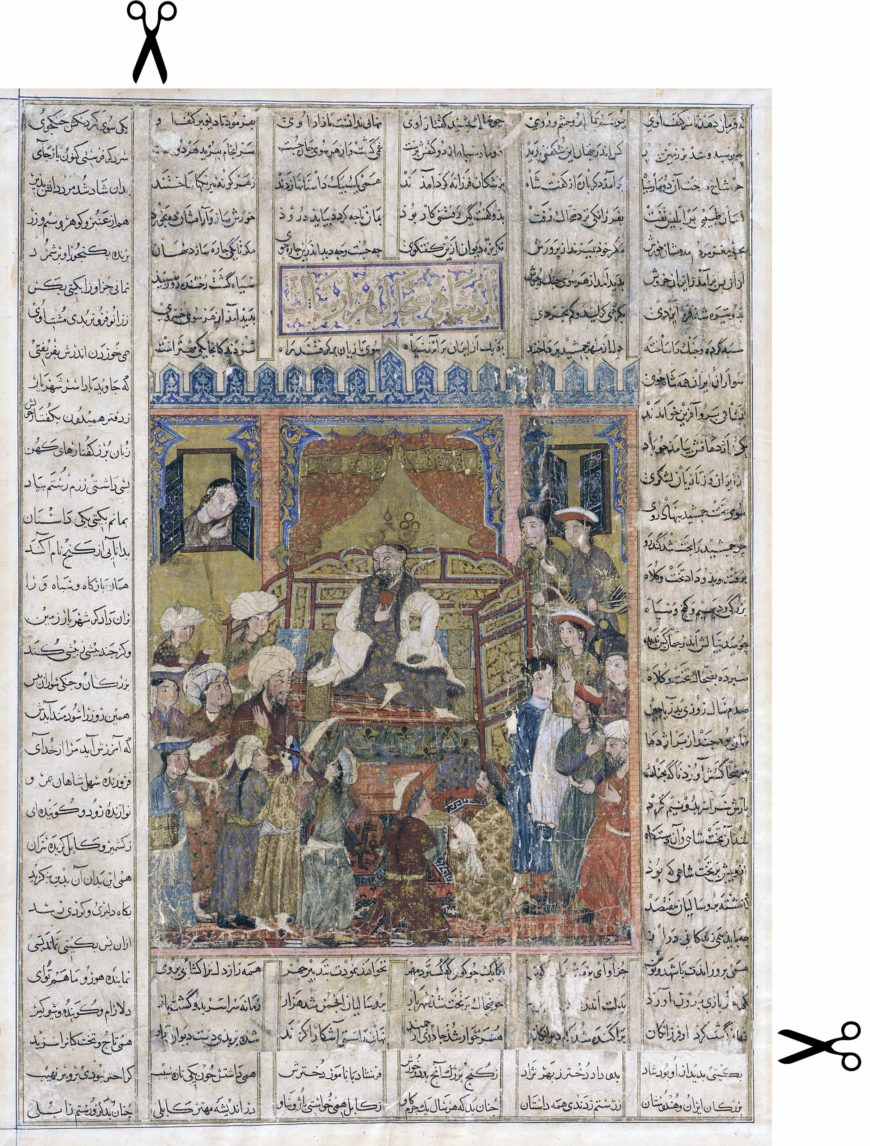

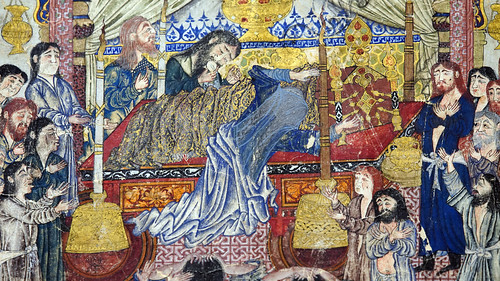

The Tahmasp Shahnama is given to an Ottoman sultan

The Tahmasp Shahnama had a different trajectory. It remained prized at Tahmasp’s court for a few years, as the court librarian Dust Muhammad extolled its painting of “The Court of Kayumars” in an album preface written in 1544, and two illustrated folios were replaced for unknown reasons. But then in 1566 Tahmasp, who had apparently tired of painting and dispersed his royal workshop, decided to give the manuscript to the Ottoman sultan Selim II to mark his succession. Tahmasp sent the Shahnama at the head of a long camel train along with a Qurʾan manuscript attributed to the hand of Prophet’s son-in-law ʿAli ibn Abi Talib, books chosen to emphasize the shah’s royal and religious pedigree and show up his rival as a mere parvenu.

The Ottomans got the message, and their reception of the embassy and its gifts was just as orchestrated. They produced their own richly illustrated dynastic histories, including one with a painting showing the enthroned Selim loftily accepting the gifts from groveling ambassadors as a form of entitled tribute rather than an exchange between equals.

The Ottomans sequestered the Tahmasp Shahnama in their royal library. It may have been examined occasionally, as details of the Safavid paintings are occasionally repeated in Ottoman manuscripts, but the lack of fingerprints, smudges, creases, and other marks show that few people consulted the volume. One exception was Mehmed ʿArif Efendi, keeper of guns at the court treasury, who added synoptic commentaries about the paintings in Ottoman Turkish in 1800–01. Written on polished sheets that were glued into the manuscript opposite the illustrated pages, these synopses suggest that readers at the Ottoman court, which by this point used Ottoman Turkish, merely flipped through the Persian text, looking only at the paintings.

Cutting up the Great Mongol Shahnama

The situation for these and many other illustrated manuscripts changed dramatically at the turn of the twentieth century with political upheavals in the Islamic lands and the growing power of Europe and the art market there. Impoverished courtiers apparently filched manuscripts from royal libraries and sold them to European and American dealers and collectors who had developed a taste for richly illustrated texts. The Tahmasp Shahnama was the first of the two manuscripts to go. By 1903 it had moved, perhaps via Iran, to Paris where it entered the collection of Baron Edmund de Rothschild.

The Great Mongol Shahnama left a few years later, and by 1910 it was in the hands of the Belgian collector Georges Demotte. Unable to sell the whole manuscript, perhaps because of the looming threat of war in Europe, Demotte decided to cut it up and hawk the folios separately to collectors who could display them framed, hanging on the wall. Demotte was faced with a problem, however, as some folios had paintings on both sides.

To maximize his profits, he had the two sides of the folio pulled apart and then remounted the pages separately (such as “Zahhak enthroned” and “Faridun mourning his son”) or had the detached paintings pasted onto other folios (such as “Faridun goes to Iraj’s palace and mourns”).

In doing so, he damaged some of the pages. Many of them are abraded because of the paper sheets that were temporarily glued on to help separate the two sides of the folio. In a few cases, parts of the folio, including the painted area, were damaged. Some entire pages or folios may have been destroyed. All together, Demotte is known to have sold 58 illustrated folios and a handful of text folios that were attached to them so that collectors could frame a double-page spread to resemble an open book. The rest of this magnificent manuscript, with some of the most emotional scenes ever produced in Persian painting, is missing, likely destroyed.

The dispersal of the Tahmasp Shahnama

The Tahmasp Shahnama again followed a different course. Two years after the death of Baron Rothschild’s son Maurice in 1957, the manuscript, intact with all of its 258 paintings, was sold to the American magnate and bibliophile Arthur A. Houghton, Jr. who commissioned the American scholars Martin Dickson and Stuart Cary Welch to prepare a lavish monograph that reproduced all 258 illustrated pages at full size. To make the plates for publication, the volume had to be unbound, a step that presaged its dispersal.

Small groups of paintings, now framed in silk mats, were exhibited starting in 1962 at the bibliophilic Grolier Club in New York, of which Houghton was president. At this time the international art market was heating up, and works of Middle Eastern, particularly Persian, art were in high demand. Empress Farah of Iran was a major collector, and texts like the Shahnama that reflect the glories of Iranian kingship were particularly popular in this imperial era. Houghton, who was in the midst of divorcing his third wife and marrying his fourth, began to auction off his rare books. In 1970 when The Metropolitan Museum of Art celebrated its centennial, Houghton, then chairman of the board, donated 76 illustrated folios from the Tahmasp Shahnama to it. He needed to establish a tax basis for his donation, and beginning in 1976, individual folios appeared for sale on the market. The first seven comprised works by all the major painters that Dickson and Welch assigned to the manuscript, thereby establishing a unit price for works by different hands.

More sales followed, some to connoisseurs like Prince Saddrudin Aga Khan who acquired what is regarded as the finest painting in the manuscript, “The Court of Kayumars,” but others (such as “Faridun strikes down Zahhak”) went to investors such as the British Rail Pension Fund.

The manuscript’s peregrinations did not end there. Following the Iranian Revolution of 1979, the art market changed and uproar over the manuscript’s crass dismemberment increased. After Houghton’s death in 1990, his son decided to sell intact the carcass of the manuscript, including its binding and 118 remaining paintings. Complex negotiations through the London dealer Oliver Hoare led to an arrangement in 1994 with the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tehran to trade the manuscript’s remains for a 1953 Willem de Kooning painting, Woman III, a large oil of a standing nude purchased by Empress Farah but considered distasteful in the Islamic Republic. In a scene worthy of a Graham Greene thriller, the trade-off took place one rainy night on the tarmac of Vienna airport. The manuscript, disbound and deprived of its finest paintings, returned to its homeland where it was feted as a national treasure.

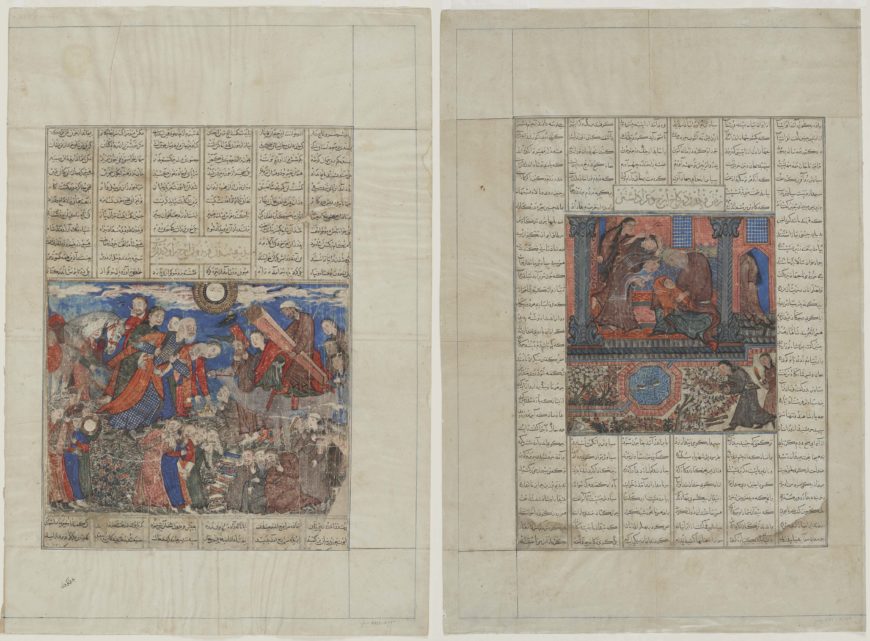

Reconstructing the manuscripts today

It is impossible to undo the damage suffered in dismembering these manuscripts, but scholars have pursued several strategies to help us appreciate some of their original glories. Each approach brings different benefits, but also entails certain limitations. Exhibitions of disbursed folios allows viewers to compare folios side by side, especially important in the case of the Great Mongol Shahnama in which the individual paintings differ so widely. But some museums are prohibited from lending, and few would risk sending all of their folios from one manuscript at a single go.

Another approach is to produce a handsome monograph with full-size color illustrations of all the folios, as Sheila Canby did with the Tahmasp Shahnama to celebrate the poem’s millennium in 2010. The book showcases the wonders of the images, but privileges paintings over poetry and downplays the manuscript as the integral work of art. Calligraphers, heirs to two centuries of tradition in transcribing this text, wanted to have the lines describing the action frame the painting. To do so, they manipulated the layout.

In the case of the “The Angel Surush rescues Khusraw Parviz,” for example, the calligrapher wrote some of the lines on the front side of the folio diagonally so that the page contains only 12 lines of text instead of the standard 22, and the couplets describing the angel’s descent fall next to the painting on the reverse. The diagonal layout signals to readers that an illustration is approaching and heightens their anticipation in turning the page.

A digital reconstruction of the manuscript would allow the reader to sense the rhythm while flipping the pages, but such an enterprise is exceedingly difficult given that this manuscript is divided between two major institutions in the U.S. and Iran, with additional folios scattered among dozens of public institutions and private collectors, with some still changing ownership. Furthermore, books in the Islamic lands were never meant to be seen flat, as the bindings allow them to be opened only 110 degrees. Instead, books were read three-quarters open while supported on a cradle or stand. So images of a two-page spread flat on a computer screen directly in front of viewers are distorted and do not convey the original aspect of reading the book. Nevertheless, all of these approaches help us to visually reconstruct these glorious illustrated books, in the words of the Safavid chronicler Dust Muhammad, the likes of which the celestial spheres have never seen.

Notes:

- For the Great Mongol Shahnama, we cannot say exactly how large the folios were since it was remargined, but the written area is more than twice that of the Tahmasp Shahnama (1160 vs 486 sq. cm.) The larger area of writing in the Great Mongol Shahnama allowed for more columns (six vs. four) and more lines (31 vs. 22) per page.

Additional resources

The Court of the Gayumars (Kayumars), Smarthistory video

Folio from a Shahnama, The Bier of Iskandar (Alexander the Great), Smarthistory video

Read more about “Bahram Gur in a Peasant’s House,” a folio from the so-called Second Small Shahnama

Read more about “Bahram Gur Fights the Karg (Horned Wolf),” from the Great Mongol Shahnama

How a page is split, short video from The Morgan Library and Museum

Sheila Blair, “Reading a Painting: Sultan-Muhammad’s The Court of Gayumars,” in The Empires of the Near East and India: Source Studies of the Safavid, Ottoman, and Mughal Literate Communities, ed. Hani Khafipour (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019): 525–38.

Sheila R. Canby, The Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp: the Persian Book of Kings (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014).

Martin B. Dickson and Stuart Cary Welch, The Houghton Shahnama (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982).

Oleg Grabar and Sheila Blair, Epic Images and Contemporary History: The Illustrations of the Great Mongol Shah-Nama (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Folio from a Shahnama, The Bier of Iskandar (Alexander the Great)

by DR. MASSUMEH FARHAD, FREER GALLERY OF ART and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

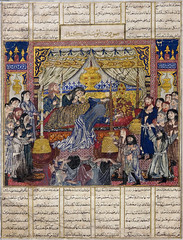

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): The Bier of Iskandar (Alexander the Great), folio from the Great Mongol Shahnama (Il-Khanid dynasty, Tabriz, Iran), c. 1330, ink, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 57.6 x 39.7 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1938.3). Speakers: Dr. Massumeh Farhad, Chief Curator and The Ebrahimi Family Curator of Persian, Arab, and Turkish Art, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution and Dr. Steven Zucker.

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The Court of Gayumars

by DR. NANCY DEMERDASH, DR. FILIZ ÇAKIR PHILLIP, CURATOR, AGA KHAN MUSEUM and DR. MICHAEL CHAGNON, CURATOR, AGA KHAN MUSEUM

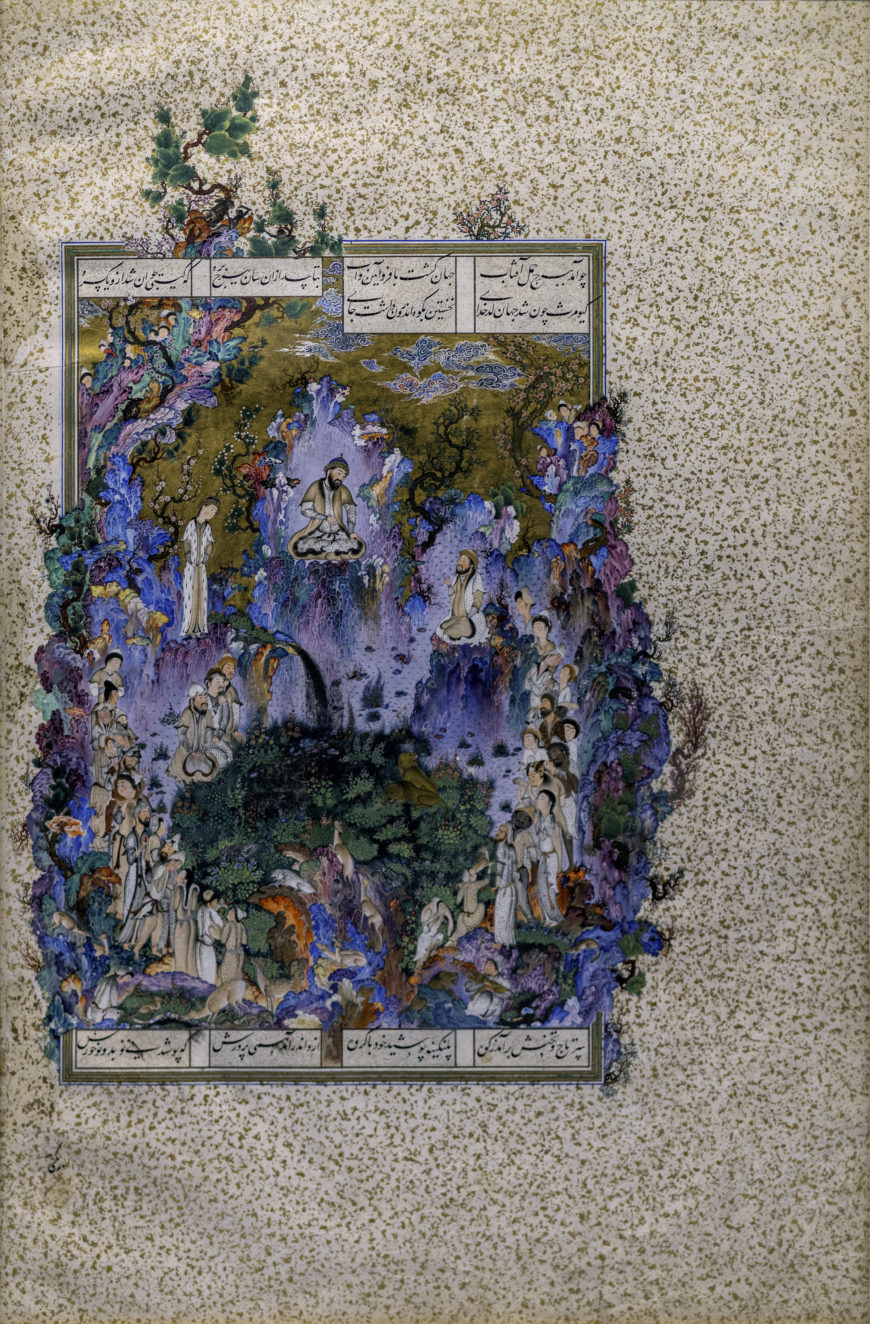

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Sultan Muhammad (attributed), The Court of Kayumars (Safavid: Tabiz, Iran), c. 1524–1525, from the Shah Tahmasp Shahnameh, c. 1524–35, opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper, 45 x 30 cm (Aga Khan Museum, Toronto) speaker: Dr. Michael Chagnon, Curator, Aga Khan Museum and Dr. Steven Zucker

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Sultan Muhammad (attributed), The Court of Kayumars (Safavid: Tabiz, Iran), c. 1524–1525, from the Shah Tahmasp Shahnameh, c. 1524–35, opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper, 45 x 30 cm (Aga Khan Museum, Toronto) speakers: Dr. Filiz Çakir Phillip, Curator, Aga Khan Museum and Dr. Steven Zucker

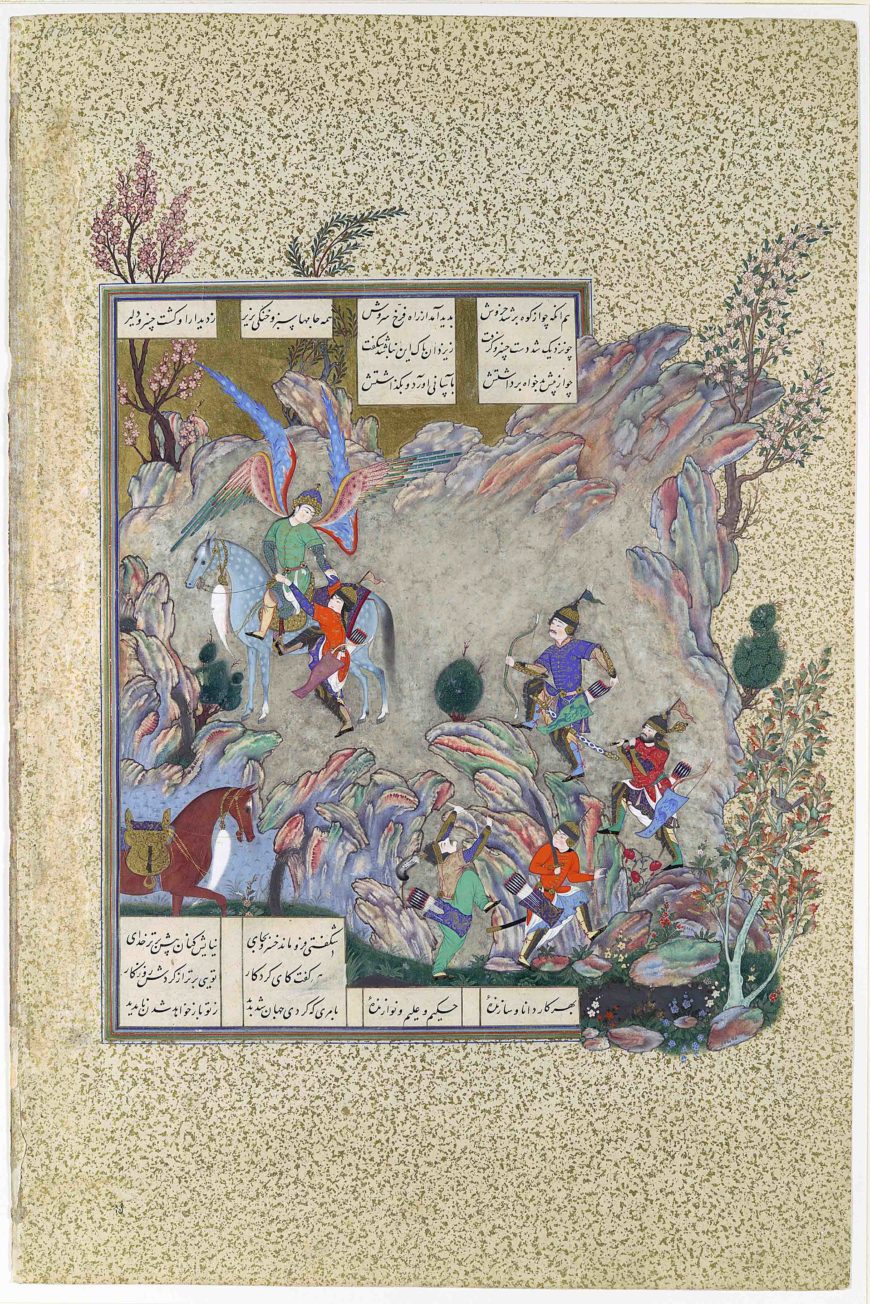

The Shahnama

This sumptuous page, The Court of Gayumars (also spelled Kayumars— see top of page, details below and large image here), comes from an illuminated manuscript of the Shahnama (Book of Kings)—an epic poem describing the history of kingship in Persia (what is now Iran). Because of its blending of painting styles from both Tabriz and Herat (see map below), its luminous pigments, fine detail, and complex imagery, this copy of the Shahnama stands out in the history of the artistic production in Central Asia.

The Shahnama was written by Abu al-Qāsim Ferdowsi around the year 1000 and is a masterful example of Persian poetry. The epic chronicles kings and heroes who pre-date the introduction of Islam to Persia as well as the human experiences of love, suffering, and death. The epic has been copied countless times—often with elaborate illustrations (see another example here).

Safavid patronage

This particular manuscript of the Shahnama was begun during the first years of the 16th century for the first Safavid dynastic ruler, Shah Ismail I, but was completed under the direction of his son, Shah Tahmasp I in the northern Persian city of Tabriz (see map below). The Safavid dynastic rulers claimed to descend from Sufi shaikhs—mystical leaders from Ardabīl, in northwestern Iran. The name “Safavid” stems from one particular ancestral Sufi, named Shaykh Safi al-Din (literally translated as “purity of the religion”). Over a two-hundred-year span starting in 1501, the Safavids controlled large parts of what is today Iran and Azerbaijan (see map below). The Safavids actively commissioned the building of public architectural complexes such as mosques (image below), and they were patrons of the arts of the book. In fact, manuscript illumination was central to Safavid royal patronage of the arts.

Depicting figures

It is often assumed that images that include human and animal figures, as seen in the detail below, are forbidden in Islam. Recent scholarship, however, highlights that throughout the history of Islam, there have been periods in which iconoclastic tendencies waxed and waned.1 That is to say, at specific moments and places, the representation of human or animal figures was tolerated to varying degrees.

There is a long figural tradition in Persia—even after the introduction of Islam—that is perhaps most evident in book illustration. It is also important to note that, unlike the neighboring Ottoman Empire to the west who were Sunni and in some ways more orthodox, the Safavids subscribed to the Shi’i sect of Islam.

Two centers of culture

Although it is widely recognized that the conventions of what is sometimes termed “classical”2 Persianate painting had become established by the fourteenth century, it is in the reign of Shah Tahmasp I that we see the most dramatic advancements in illumination and the arts of the book more generally.3 His patronage of this specific art form is in part due to his own painting studies in Herat (in the western region of present-day Afghanistan) and Tabriz (in the northwestern region of present-day Iran), under Bihzad and Sultan Muhammad, respectively.4 Both cities were major centers for the production of manuscript illuminations. While the entire manuscript of the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp I consists of approximately 759 illustrated folios and 258 miniatures all produced over the span of several years,5 this particular miniature is attributed to the workshop of Sultan Muhammad, according to Dust Muhammad, an artist and historian from this period.6 In 1568, this lavish Shahnameh was given as a gift by Shah Tahmasp I to the Ottoman Sultan, Selim II.7

King of the world

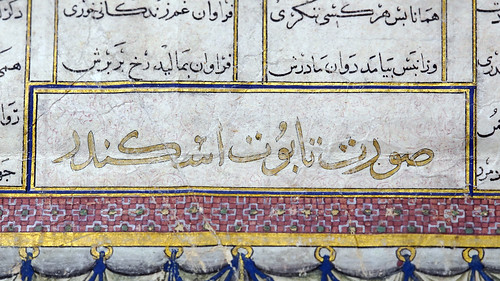

There are several interpretive issues to keep in mind when analyzing Persianate paintings. As with many of the workshops of early modern West Asia, producing a page such as the Court of Gayumars often entailed the contributions of many artists. It is also important to remember that a miniature painting from an illuminated manuscript should not be thought of in isolation. The individual pages that we today find in museums, libraries, and private collections must be understood as but one sheet of a larger book—with its own history, conditions of production, and dispersement. To make matters even more complex, the relationship of text to image is rarely straightforward in Persianate manuscripts. Text and image, within these illuminations, do not always mirror each other.8 Nevertheless, the framed calligraphic nasta’liq (hanging)—the Persian text at the top and bottom of the frame (image above) can be roughly translated as follows:

When the sun reached the lamb constellation,9 when the world became glorious,

When the sun shined from the lamb constellation to rejuvenate the living beings entirely,

It was then when Gayumars became the King of the World.

He first built his residence in the mountains.

His prosperity and his palace rose from the mountains, and he and his people wore leopard pelts.

Cultivation began from him, and the garments and food were ample and fresh.10

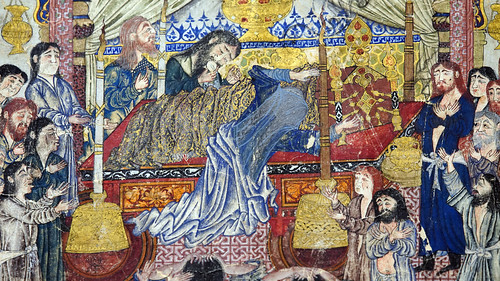

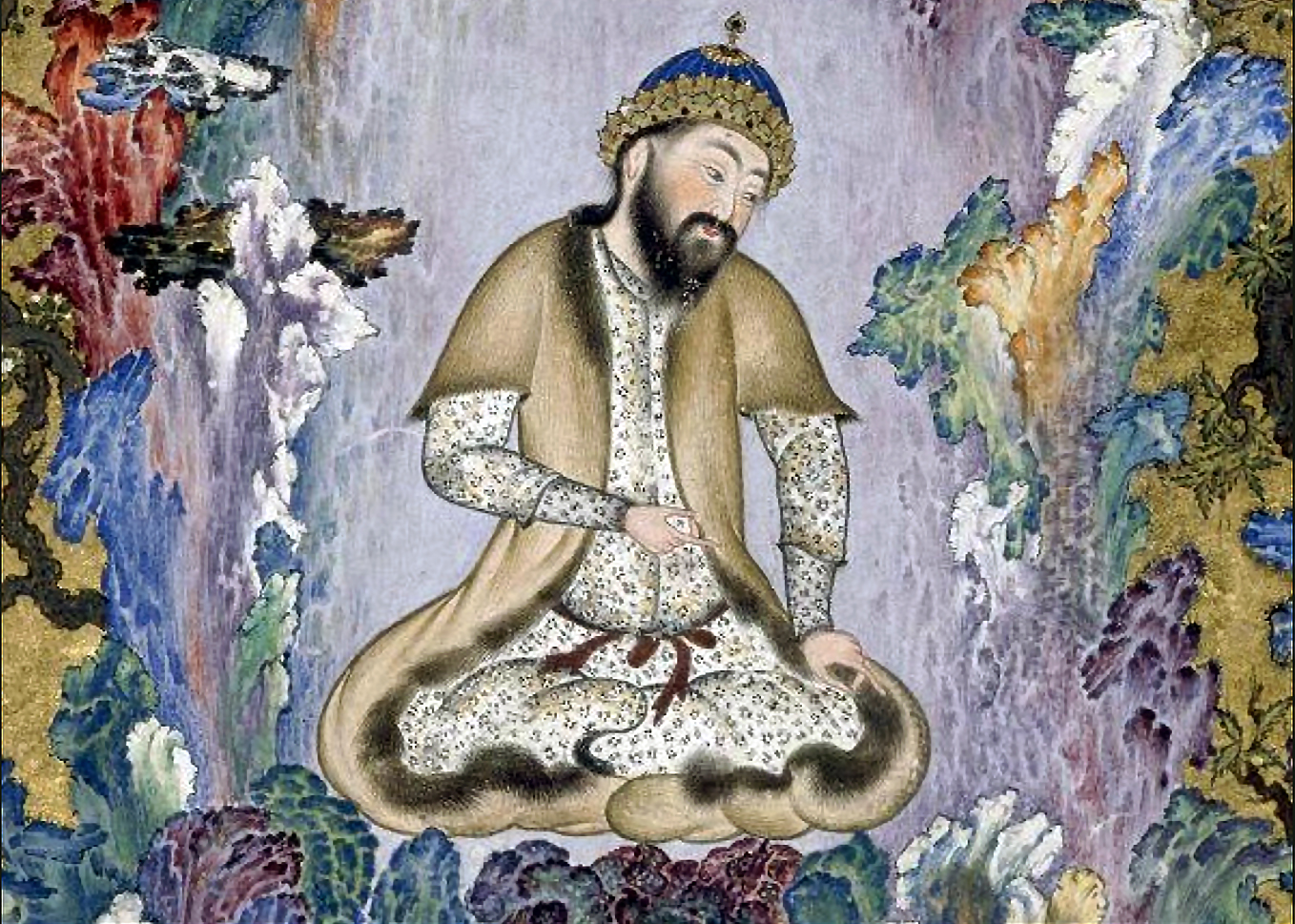

Dense with detail

In this folio (page), we can see some parallels between the content of the calligraphic text and the painting itself. Seated in a cross-legged position, as if levitating within this richly vegetal and mountainous landscape, King Gayumars rises above his courtiers, who are gathered around at the base of the painting. According to legend, King Gayumars was the first king of Persia, and he ruled at a time when people clothed themselves exclusively in leopard pelts, as both the text and the represented subjects’ speckled garments indicate.

Perched on cliffs beside the King are his son, Siyamak (left, standing), and grandson Hushang (right, seated).11 Onlookers can be seen to surreptitiously peer out from the scraggly, blossoming branches onto King Gayumars from the upper left and right. The miniature’s spatial composition is organized on a vertical axis with the mountain behind the king in the distance, and the garden below in the foreground. Nevertheless, there are multiple points of perspective, and perhaps even multiple moments in time—rendering a scene dense with details meant to absorb and enchant the viewer.

One might see stylistic similarities between the swirling blue-gray clouds floating overhead with pictorial representations in Chinese art (image above); this is no coincidence. Persianate artists under the Safavids regularly incorporated visual motifs and techniques derived from Chinese sources.12 While the intense pigments of the rocky terrain seem to fade into the lush and verdant animal-laden garden below, a gold sky canopies the scene from above. This piece—in all its density color, detail, and sheer exuberance—is a testament to the longstanding cultural reverence for Ferdowsi’s epic tale and the unparalleled craftsmanship of both Sultan Muhammad and Shah Tahmasp’s workshops.

Notes

1. See Christiane Gruber, “Between Logos (Kalima) and Light (Nūr): Representations of the Prophet Muhammad in Islamic Painting,” Muqarnas 16 (2009), pp. 229-260; Finbarr B. Flood, “Between Cult and Culture: Bamiyan, Islamic Iconoclasm, and the Museum,” The Art Bulletin 84, 4 (December 2002), pp. 641-659; Christiane Gruber, “The Koran Does Not Forbid Images of the Prophet,” Newsweek (January 9, 2015).

2. For a helpful analysis of the historiographic ascription of the term ‘classical’ to Persian painting and the cultural hierarchy that was established largely by scholar-collectors in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, see Christiane Gruber, “Questioning the ‘Classical’ in Persian Painting: Models and Problems of Definition,” in the Journal of Art Historiography 6 (June 2012), pp. 1-25.

3. David J. Roxburgh, “Micrographia: Toward a Visual Logic of Persianate Painting,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 43 (Spring 2003), pp. 12-30.

4. Sheila Canby affirms Stuart Cary Welch’s estimate that it took Sultan Muhammad and his workshop three years to complete the Court of Gayumars illustration. Sheila Canby, The Golden Age of Persian Art, 1501-1722 (New York: Abrams, 2000), p. 51.

5. David J. Roxburgh, “On the Brink of Tragedy: The Court of Gayumars from Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnama (‘Book of Kings’), Sultan Muhammad,” in Christopher Dell, ed., What Makes a Masterpiece: Artists, Writers and Curators on the World’s Greatest Works of Art (London; New York: Thames & Hudson, 2010), pp. 182-185; 182. The text was subsequently possessed by Baron Edmund de Rothschild and then sold to Arthur A. Houghton Jr, who in turn sold pages of the book individually.

6. Roxburgh, “Micrographia: Toward a Visual Logic of Persianate Painting,” p. 19. “In the Persianate painting, however, image follows after word in a linear sequence; the text introduces and follows after the image, but it is not actually read when the image is being viewed…In the Persian book the act of seeing is initiated by a process of remembering the narrative just told. Moreover, that text does not prepare the viewer for what will be seen in the painting.”

7. This expression denotes the beginning of spring.

8. I am grateful to Dr. Alireza Fatemi for generously providing this translation.

9. Roxburgh, “On the Brink of Tragedy,” p. 182.

Additional resources:

The Court of Gayumars at the Aga Khan Museum

Large image here (click for full-size)

Biography of the poet Abu al-Qāsim Ferdowsi, Encyclopaedia Iranica

The Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Iconoclasm in the Netherlands in the Sixteenth Century

Different church interiors — Calvinist (Protestant) and Catholic

In paintings by seventeenth-century Dutch artist Pieter Saenredam, the interiors of Calvinist churches often appear as blank, sterile spaces with white walls, clear glass windows, and a notable lack of decoration. We know from his meticulous preparatory drawings that Saenredam was a precise artist, and although he sometimes did make changes to the interiors he represented, they were by and large emblematic of what Dutch Calvinist sacred space was like. By contrast, Pieter Neefs’s contemporary paintings of Flemish Catholic religious spaces — which contain a profusion of small altars and devotional artwork — reflect a distinctly different attitude about decoration, materiality, and piety. The difference between Calvinist and Catholic churches persists to this day.

Breaking idols

Some of these differences can be attributed to two intertwined events of the sixteenth century that transformed the Low Countries (a lowland region in northern Europe that includes Belgium and the Netherlands): the prioritization of the written word in the theological reforms of the Protestant Reformation and the Iconoclasm (or Beeldenstorm) of 1566. The word “iconoclasm” refers to any deliberate destruction of images. Instances of iconoclasm can be found from the ancient world to contemporary events, such as the 2015 destruction of Palmyra in Syria by ISIS or the elimination of the Bamiyan Buddhas by the Taliban in 2001.

Here, iconoclasm specifically refers to the events of 1566 in an area that we now know as Belgium and the Netherlands. Prior to 1566, most churches in this region would have been largely encrusted with ornament: guilds commissioned altarpieces for their chapels while private patrons donated memorial paintings, endowed tomb sites, and donated elaborate shrines or ritual vessels. Piety was made visible in the material culture of the church, paralleling a northern European explosion in personal devotional artwork in the form of manuscripts, woodcut prints, carved boxwood shrines and prayer beads, and small paintings.

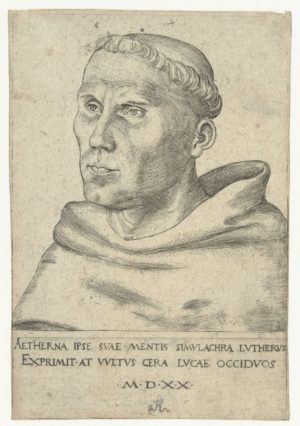

Protestant change

The sixteenth century was a time of significant religious change. According to legend, in 1516, Luther nailed his 95 Theses to a church door in Wittenberg and criticized what he perceived as corrupt practices within the Catholic Church. Following Luther, numerous other Northern European reformers shifted away from the Catholic Church centered in Rome. Among other more systemic and doctrinal issues, the reformers also had complicated relationships with religious imagery.

Controversy over the nature of religious images was not new in the sixteenth century. The same tension had rocked the Byzantine Empire in the eighth and ninth centuries. Like the earlier Byzantine case, strict reformers believed images were inherently sinful.

The northern humanist Desiderius Erasmus noted that the physical veneration of an object made it an active agent and turned it into an idol, pushing the objects and images traditionally at the heart of northern European piety into the zone of the idolatrous. Therefore, to use an image as part of your prayers creates idols — the very sin explicitly condemned in the Second Commandment, which reads:

You shall have no other gods before me. You shall not make for yourself a graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth; you shall not bow down to them or serve them; for I the LORD your God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children to the third and the fourth generation of those who hate me, but showing steadfast love to thousands of those who love me and keep my commandments. Exodus 20:3

Luther himself was not entirely anti-image, stating that if there was no sin in the heart, there was no risk in seeing images with your eyes. However, the faithful needed to remove the roots of sin in themselves; they needed to worship God and not a material object which takes the place of God. Luther later clarified that what the second commandment prohibited was images of God; images of saints or crucifixes were not condemned by him as they serve as memorials.

By 1566, the debate about the line between “an image of a religious figure or story that aided in devotional practice” and “an idolatrous object which took the place of God in the sinful heart of the viewer” had been heavily contested for close to fifty years. The precise nature of the debate varied widely based on location, and violence against images erupted at different times in different cities throughout Germany, Switzerland, The Netherlands, Belgium, and England.

The debate about the nature of images seems abstract and it is impossible to know to what extent the theological details were the motivations of any specific iconoclast. In the case of the Beeldenstorm of 1566, we can focus on a few factors to more closely examine one particular case and the intersection of tensions that led to violence. Studying the Beeldenstorm is complicated by the fact that it took many different forms depending on the local conditions and the range of responses to both religious and political circumstance.

Church, state, and other complex issues

Debates over religious imagery occurred at the same time as other complex disputes. Political tensions were running high. At the time, most of the land that now constitutes The Netherlands and Belgium was the Spanish Netherlands — an assortment of territories brought together through marriages and dynastic alliances and owing fealty to the King of Spain.

Through the abdication of the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, Charles V, in 1556 and the ascension of Philip II to the throne of Spain, Netherlanders were becoming increasingly unhappy. The Spanish Crown supported an aggressive Catholic identity and agenda and vigorously pursued heretics (anyone not practicing Catholicism in line with the teachings of the Church in Rome).

The Spanish Inquisition existed specifically to root out those who were not Catholic enough. Though we tend to think of the Inquisition as something confined to the Iberian peninsula (Spain and Portugal), it also had a significant impact on Northern Europe. A branch of the Inquisition operated there which was overseen by Margaret of Parma (the illegitimate daughter of Philip II who had been appointed regent and reported to her father). In response to petitions filed by the local nobility, Margaret ended the Inquisition in 1564 in an attempt to broker peace and avoid outright rebellion. A group who came to be called the Gueux brought further petitions in 1566 to try to end ongoing persecution. The tensions surrounding religious persecution were made worse by several bad harvests, prolonged and widespread famine, particularly harsh winters, and new taxes.

“Hedge preachers” as rebellious leaders

Religious, political, and economic issues were closely intertwined. To a Flemish Protestant, the Spanish Catholic Crown represented religious and political oppression. This was made worse by the widening cultural and linguistic gap between the Spanish Crown and its Flemish subjects. These tensions were brought to a boil by hagenprekers, or “hedge preachers,” wandering figures who whipped up anti-Spanish and anti-Catholic sentiment in sermons held outdoors, and usually outside of city walls and therefore beyond easy jurisdiction.

Several scholars have argued that Pieter Bruegel’s painting, The Sermon of Saint John the Baptist, represents this biblical event as if it were happening in the current political climate. John the Baptist, here cast as a hedge preacher, almost disappears into the crowd; Jesus, who he is introducing, is even less noticeable. Typically for Bruegel, the crowd of people gathered to listen to the speaker are from all walks of life and dressed in contemporary Flemish clothing.

One face stands out in the crowd because he unexpectedly faces the viewer: a man in a black hat having his palm read in the foreground. He would have been identifiable to contemporary viewers as dressed in a Spanish mode, and fortune telling would have been seen as corrupt and popish.

The Spaniard alone ignores the humble John the Baptist in favor of giving in to superstitious practices, while two monks in the front right look on with expressions that could be interpreted as jeers and skepticism. As a result, Bruegel’s painting possibly functions simultaneously as a biblical scene and a contemporary political polemic, containing just enough ambiguity to not ruffle Inquisitorial feathers.

Iconoclastic riots

The hedge preachers were at least partially responsible for the ignition of the Beeldenstorm, the sudden outbreak of violence against religious images that began in the summer of 1566 and spread throughout the Low Countries. In response to their anti-Catholic preaching, violence began in West Flanders and radiated outward.

In some towns, it was outright mob violence: groups of people burst into churches, smashing windows and sculptures. In other cities, the destruction of religious images was systematic and either openly or covertly supported by the local government. In some cases, the iconoclasts and the local Catholic Church officials negotiated for the survival of certain artworks.

It was a fever that spread throughout the Low Countries, leaving few towns untouched by the sudden explosion of anti-image sentiment. According to Alistair Duke, the destruction of images functioned as a ritualistic act intended to prove to both Catholics and Protestants that the images were powerless. If images were indeed sacred conduits that connected the faithful to God, they would defend themselves; since it was possible to destroy them, they were therefore earthly vanity and merely distractions from truth.

To destroy the objects and ritually humiliate them was to reject the broader political and religious structures they represented, as well. Sculptures were torn down from their niches, windows were smashed, and altars and shrines were disassembled and burned.

When the sculptures were part of the fabric of the building and could not be easily removed, the heads of the figures were hacked off. Examples reflecting this kind of violence remain visible in churches throughout the Northern Low Countries inside previously Catholic, now Protestant churches.

Iconoclasm in 1566 was not just the result of doctrinal disagreement about the nature of religious imagery and the interpretation of biblical text. It was instead a response to intertwined issues of politics, religious oppression, and economic factors. It was one spark that helped ignite the flames of the Eighty Years War, a war that ultimately resulted in the split between the northern Calvinist provinces of the Dutch Republic and the southern Catholic province that remained connected to Spain. As much as the violence of the Beeldenstorm itself may have been short-lived, the broader cultural and historical changes that cascaded as a result had permanent and far-reaching consequences.

Additional resources:

Read more about the Beeldenstorm in the Low Countries Historical Review

David Freedberg, The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1989).

Alistair Duke, “Calvinists and Papist Idolatry: the Mentality of the Image-breakers in 1566,” in Dissident identities in the early modern Low Countries, ed. Pollman and Spicer (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2009).

Submerged, burned, and scattered: celebrating the destruction of objects in South Asia

A photograph by artist Ketaki Sheth depicts a little girl, wearing a lacy floral dress and standing upon the shoulders of a man, perhaps her father, to get a better view of the surrounding crowd that carries a large sculptural image of the Hindu god Ganesha. Sheth captures a moment of stillness during an otherwise boisterous and energetic occasion: the artist brings us above the crowd and into the clouds that backlight the richly adorned body of the elephant-headed deity—remover of obstacles and son of Shiva and Parvati—on his way toward a body of water for ritual immersion during the annual festival of Ganesha Chaturthi.

Impermanence and belief

The practice of ritually submerging, and thereby destroying, sculptural images of Ganesha during Ganesha Chaturthi represents one of several religious and cultural acts in South Asia which complicate ideas about the value and permanence of material objects. Makers involved in these practices produce objects and artistic depictions with the knowledge that the products of their creative labor are temporary and will be intentionally destroyed or deteriorate over time. In some cases these practices of ritual destruction resonate with ideas about the cyclical nature of time as described in concepts like samsara. In other cases the destruction of an object is symbolic of the removal of evil and the restoration of good in the universe. In still other cases, we find beautifully wrought material objects whose impermanence is embedded in their form and function, much like disposable paper plates.

These examples challenge us to push against the preciousness of objects—an approach that we encounter so often in the study of art—and to rethink the way we value the permanence / impermanence of material things. This call to rethink our valuation of objects is also critical to the decolonizing of the discipline of art history; privileging objects of durable and precious materials over ephemeral works of art (such as things made from unfired clay, paper, or cotton fiber) is in many ways a legacy of British colonial rule on the subcontinent that sought to promote a Eurocentric view and valuation of objects and artistic practices.[1]

For the Ganesha images created in celebration of Ganesha Chaturthi, their destruction is a joyous celebration. Occurring in August or September of each year according to the Hindu lunar calendar, the ritual immersion of Ganesha marks the deity’s birth and symbolic return to the earth. [2] According to legend, Ganesha was created from clay by the goddess Parvati and was given an elephant’s head after his father, the god Shiva, inadvertently beheaded him. Ganesha Chaturthi celebrates the moment when the deity received his elephant head, and his ritual immersion in water each year following ten days of rites is a significant event that bestows blessings on devotees.

Immersion as purification

It is not surprising that worshippers laboriously carry sacred sculptural images or murtis of Ganesha to local bodies of water for ritual immersion. Water is a symbolic purifier in South Asia and used in numerous religious and cultural practices connected with worshipping Hindu gods and goddesses as well as honoring holy figures, saints, and sacred architecture in Buddhist, Christian, Jain, Muslim, and Sikh beliefs. For the Hindu devotees participating in ritual immersion festivals like Ganesha Chaturthi, the water itself is sacred and ultimately connected to the holiest river in India, the Ganga.[3]

Historically, artists made disposable or perishable murtis of the god from unfired clay or low-fired terracotta decorated with natural pigments. [4] These images would slowly dissolve in water and eventually be reincorporated into the ecosystem. However, over the last several decades increasingly larger Ganesha images made from synthetic paints, gypsum plaster (plaster of Paris), and plastic ornaments have become popular, and the heavy metals and toxins associated with these raw materials have leached into India’s waterways, creating dangerous amounts of pollution. [5] Recently, the Government of India’s Central Pollution Control Board established rules requiring that devotees use Ganesha murtis made from biodegradable materials (like terracotta) and have encouraged that ritual immersion practices occur in specially-designated water tanks.

In addition to annual events like Ganesha Chaturthi, the making of temporary, perishable objects and artistic depictions appear on a daily basis in many parts of India through the creation of decorative floor paintings known by various names including alpana, kollam, and rangoli. [6] Typically made by female members of a household or community using rice flour, chalk, powdered pigments, or flowers, the symmetrical forms of these temporary paintings symbolize divine power. They are intended to sanctify a space, and have ancient origins in goddess worship. [7] For special festivals some women create particularly elaborate floor paintings that last for several months or even up to a year. There are many, however, who treat this practice as a daily ritual with the intention that the painting will be swept clean and remade each morning—the epitome of intangible cultural heritage. [8]

Destroying the demon king

A particularly dramatic example of the ritual destruction of objects occurs with sculptural effigies of the demon king Ravana and his demon armies which are burned and physically torn apart during multi-day performances of the Ramacharitamanas, the Hindi version of the story of Rama which is especially popular throughout North India and famously performed in the city of Ramnagar. [9] This performance, known locally as Ramlila, narrates the story of Rama, an earthly form or avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu, who is the beloved king of the city of Ayodhya and husband to Sita, an avatar of the goddess Lakshmi. The Ramacharitamanas, similar to the Sanskrit Ramayana, describes the adventures of Rama, his brother Lakshmana, and Sita during their fourteen-year exile from Ayodhya. The story culminates in a series of battles between Rama and the powerful demon king, Ravana, who has abducted Sita and held her captive at his palace in Lanka.

In the final days of the Ramlila performance, sculptural depictions of Ravana and other demons made from bamboo and paper are set ablaze to symbolize their mythological destruction. The most dramatic moment in the Ramlila performance occurs on Dussehra, an important Hindu festival celebrated throughout India, when participants destroy sculptural depictions of Ravana, sometimes 75-feet tall and filled with firecrackers, to mark Rama’s victory over the demon king and the ultimate victory of good over evil.

In other parts of India, Dusshera is celebrated as a way to mark the goddess Durga’s victory over the buffalo demon Mahishasura, understood by devotees as a mythological act that restores dharma to the universe. Worshippers celebrate Dusshera by creating elaborate temporary altars or pandals for Durga, many of which are then submerged in water on Dusshera, marking the culmination of nine nights of celebration known as Navratri. The pandals made for the worship or puja of Durga are most famously created in Bengal where families, neighborhoods, community organizations, and businesses commission elaborate pandals that incorporate depictions of iconic architecture and motifs from popular culture. [10]

A photograph by artist Raghu Rai depicts the ritual immersion of Durga during a Dusshera celebration in Kolkata. In Rai’s image we see a larger-than-life murti of Durga being carried with bamboo poles to the Ganga by several human figures—a scene that parallels depictions of Ganesha Chaturthi. These human devotees work together to hoist the goddess into the river. We see Durga’s many arms clearly holding the weapons she uses to vanquish Mahishasura and her lion mount or vahana with its mouth agape seated nearby. A nineteenth-century painting of a similar moment suggests earlier practices of this form of ritual immersion. While the focus in the painting is on the elaborately adorned murti of Durga and the human devotees who carry her pandal in procession, in the foreground of the scene appears loose brushstrokes that hint at water, perhaps a subtle indication of the immersion to come.

Flowers and cups

The practice of ritually submerging or destroying images is not limited to depictions of gods, goddesses, or demons, but even applies to the floral garlands that adorn many sacred images. The practice of alankara or adorning a murti includes dressing the deity in strands of marigolds, roses, and jasmine flowers. Floral offerings are also used in worship at other religious sites in India including Sufi shrines, Sikh temples, and Christian churches. These flowers are most often tossed into water after their use in religious rites. Once blessed by the divine these floral offerings need to be disposed of in the holiest way possible, either scattered in a sacred river like the Ganga or immersed in a local body of water.

With increased scrutiny over environmental repercussions of such ritual practices, entrepreneurs and designers have begun to collect these discarded flowers and upcycle them into new products. Textile artist Rupa Trivedi and her team at Adiv Pure Nature have created a way to reuse flowers discarded by the Siddhivinayak Hindu temple and the Haji Ali Sufi shrine in Mumbai to create contact-dyed garments and home textiles. In these textiles the temporary floral offerings are made more permanent by imprinting their natural pigments onto cotton and silk fibers. By using water throughout the mordanting and dyeing process, Trivedi maintains the sacred connection to water that is so pivotal to ritual immersion. While Trivedi’s textiles give new life to floral offerings that would otherwise decompose into the earth, it is striking that textiles as a medium epitomize intangibility and impermanence: textiles are objects that break apart through wear and tear, fade under excessive exposure to sunlight, and deteriorate when subjected to bacteria, fungus, or invasive insects.

Perhaps the most pervasive example of the regular destruction of impermanent, temporary objects occurs through the culture of food. Ceramic artists all over South Asia produce small vessels from low-fired terracotta to be used for drinking spiced tea known as masala chai or yoghurt beverages known as lassis which are sold at roadside stands and eateries. While many vendors of chai and lassi have taken to glass, paper, plastic, and styrofoam substitutes, there are still some who prefer to use traditional clay cups. The potters who make these hand-thrown vessels do so with the knowledge that these objects will have short lives: they will be thrown to the ground or crushed underfoot after the chai or lassi has been drunk.

Much of the value of these objects lies in their impermanence and the easy way they return to the earth. While some chai or lassi cups may enter into museum collections—quintessential repositories of permanent objects—their most potent cultural value and circulation is in their temporary use and ultimate demise. As such these vessels remind us that not all tangible cultural heritage is in need of preservation, and sometimes a community requires, even celebrates, the destruction of cultural objects.

Notes:

- For an expanded discussion of colonial valuation of “fine arts” vs. “craft” within the context of unfired clay sculpture see Susan Bean, “The Unfired Clay Sculpture of Bengal in the Artscape of Modern South Asia,” in Rebecca M. Brown and Deborah S. Hutton, eds., A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture (West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, 2011), 604–628.

- Ganesha Chaturthi occurs every year on the day of Ananta Caturdasi in the month of Bhadrapada (according to the Chandramana calendar).

- For more on the sacred nature of the Ganga and its connection to other bodies of water in India, see Diana Eck, India: A Sacred Geography (New York: Random House, 2012), 131–188.

- Clay has been a material of ritual importance on the subcontinent for millennia. See Bean, “The Unfired Clay Sculpture of Bengal,” 609.

- For further discussion of the environmental implications of ritual immersion of synthetic Ganesha images see Dinesh C. Sharma, “Idol immersion poses water pollution threat” in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment (October 2014, Vol. 12, No. 8): 431; and M. Vikram Reddy and A. Vijay Kumar, “Effects of Ganesh-idol immersion on some water quality parameters of Hussainsagar Lake” in Current Science, Vol. 81, No. 11 (10 December 2001): 1412–1413.

- There are comparable ornamental patterns made on the walls of homes. See for example, Asimakrishna Dasa, Evening Blossoms: The Temple Tradition of Sanjhi in Vrndavana (New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, 1996).

- See for example, Stella Kramrisch, “The Art Ritual of Women,” in Unknown India (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1968); and Pupul Jayakar, The Earthen Drum: An Introduction to the Ritual Arts of Rural India (New Delhi: National Museum, 1980).

- Tibetan Buddhist monks are famous for creating similar temporary paintings in the form of sand mandalas. For example, see monks creating a mandala at the Rubin Museum.

- For more on the Ramlila of Ramnagar, see Richard Schechner and Linda Hess, “The Ramlila of Ramnagar” in The Drama Review: TDR, September 1977, Vol. 21, No. 3, Annual Performance Issue (September 1977): 51–82; and “Ramnagar Ramlila: All about the 200-yr-old cultural extravaganza.”

- For more on Durga Puja pandals and their makers see Bean, “The Unfired Clay Sculpture of Bengal in the Artscape of Modern South Asia,” 604–628; Tapati Guha-Thakurta, “From Spectacle to ‘Art’” in ArtIndia Vol 9, Issue 3 (Quarter 3, 2004): 34–56; Krishna Dutta, Image-Makers of Kumortuli and the Durga Puja Festival. New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2016; and Geir Heirestad, “The Durga Puja Business,” in Caste, Entrepreneurship and the Illusions of Tradition: Branding the Potters of Kolkata (Anthem Press, 2017), 1–6.

“Creative iconoclasm”: a tale of two monasteries

Conservation, restoration and ruination

Cultural heritage professionals often draw a clear distinction between conservation and restoration. The definition of conservation is closely linked with the idea of preservation—the idea is to salvage cultural artifacts so that they retain the histories that produced them.

Restoration, on the other hand, is seen as the act of replacing components that have fallen into disrepair; it can be seen as a destructive force, or as the salvation of an object from ruination. Even when restorations are done with the best intentions, and with a desire for authenticity, restoration work can alter the historical significance of building. This is especially problematic with medieval cathedrals and monasteries, which often contain an accretion of styles built up through the ages. When doing restoration, which style should be considered the “original”? Which, if any, should be removed? For some time, the Renaissance era was privileged over all others. But this began to change in the mid-nineteenth century, when medieval architecture once again began to be considered beautiful.

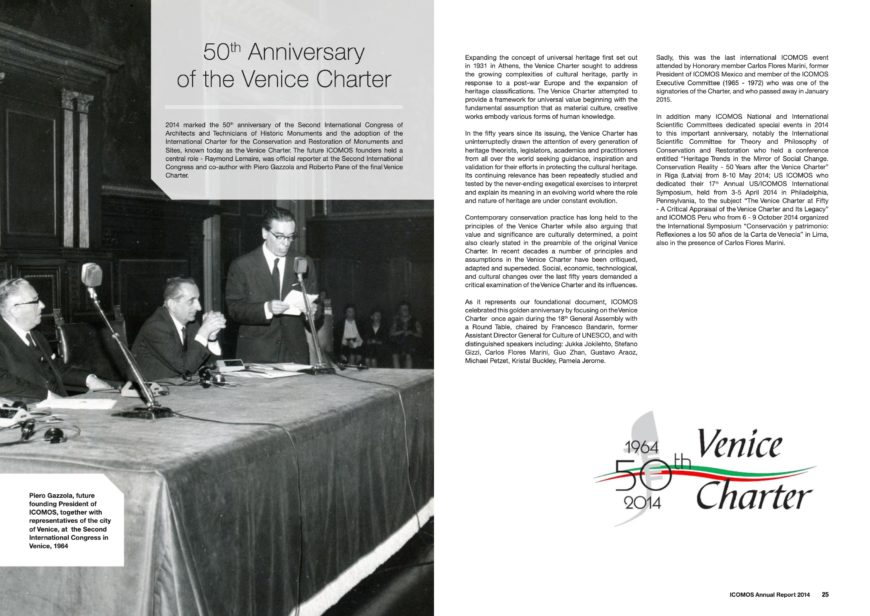

In 1964, a group of concerned conservationist professionals from various disciplines gathered from several countries to draw up guidelines in regard to responsible restoration. The document they produced, “Decisions and Resolutions: International Charter for the Conservation and Renovation of Monuments and Sites” is now referred to as The Venice Charter, and it set down rules that should be followed when restoring a historical site or monument.

In the Venice Charter, the principles of authenticity and retention of the historical context were paramount. It states that the process of restoration aims “…to preserve and reveal the aesthetic and historic value of the monument.” This goal in turn should be based on “respect for original material and authentic documents. It must stop at the point where conjecture begins.” Following this premise, the Venice Charter declared that reconstructions or replacements of missing parts “must be distinguishable from the original so that restoration does not falsify the artistic or historic evidence.” The charter also held that all significant building contributions from any time period must be considered. The Venice Charter, now almost 55 years old, is still the go-to guide in regard to historic restoration.

Creative iconoclasm

In the mid-nineteenth and early twentieth century, restoration often involved the idealized imaginings of the restorer and/or patron—something which British anthropologist Alfred Gell termed “creative iconoclasm.” Creative iconoclasm is essentially when a renovation deviates so far from the original intended form of a building that the building loses its previous meaning and takes on different meaning altogether. Hence, the use of the term iconoclasm (destruction of an image). More recently, art historian Meredith Cohen has written about the “creative interventions” done to medieval structures. They leave in their wake a whole new history, vastly different from what had been recognized for hundreds of years. Two Spanish monasteries purchased by William Randolph Hearst in the late 1920s are prime examples of these overlapping concepts.

A tale of two monasteries

You may recognize the name William Randolph Hearst (the early twentieth-century newspaper baron and avid art collector), but you may not be aware of the curious case of two Spanish medieval monasteries that made their way to the United States at his behest—the monasteries of Saint Bernard de Clairvaux (originally in Sacramenia, Spain, and now partly in Florida), and Santa María de Óvila (originally in Guadalajara, Spain, and now partly in California). [1]

Both monasteries were purchased by Hearst and arduously removed from where they had stood in Spain for hundreds of years and relocated to the United States. Both were subsequently left to moulder in fragments—one on each coast of the United States. Decades later, they would be problematically restored, at great monetary and historical cost.

The Search begins — Saint Bernard de Clairvaux

In 1923 Hearst instructed Arthur Byne, architect, art historian, and antiques dealer, to seek out a historic limestone structure. This was a decade before the Spanish Civil War, but Spain had long been experiencing political unrest and climate issues. Over the centuries, medieval Spanish monasteries had suffered the stressors of age and a general lack of religious enthusiasm.

When Byne came upon the monastery at Sacramenia, it had already experienced a severe fire in the nineteenth century, and, though repaired afterward, the last monk left in 1866. The monastery is Cistercian (a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns), and Cistercian architecture is known for its fine ashlar masonry, harmonious proportions, and restraint in ornamentation. However, there were also regional variations. Parts of the Santa María de Óvila monastery had walls seven feet thick and small, slit windows to defend the complex from Muslim invaders (the Cistercian tendency to build in remote locations made them particularly vulnerable to attack).

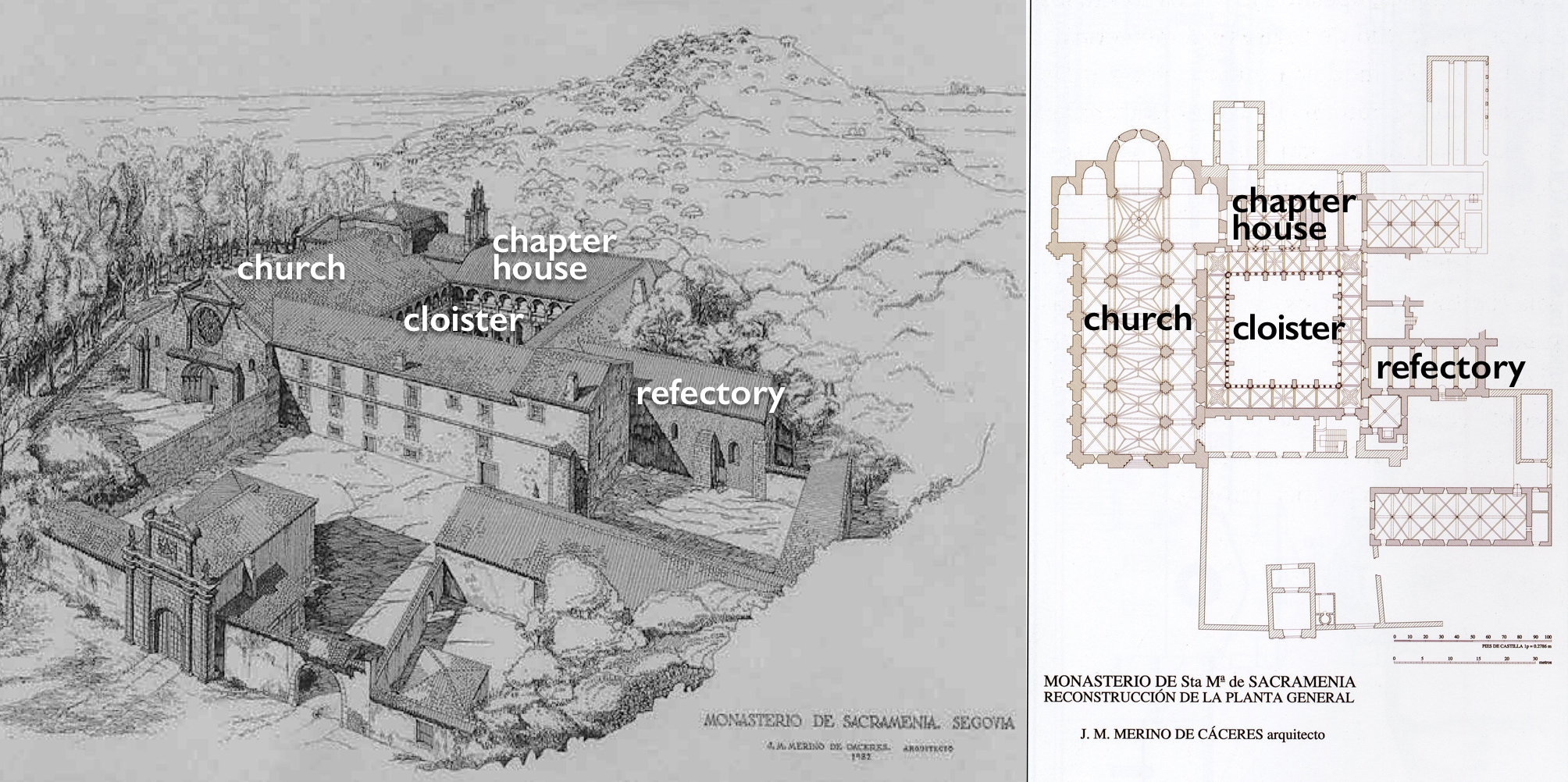

In 1923 Byne declared in a letter to Hearst and his architect Julia Morgan, “The monastery is located in one of the most desolate corners of Spain. It is of Cistercian origin, though probably the only twelfth century cloister to be had in Europe today.” The term “to be had” in this quote underlines the sort of smash and grab policy that Hearst, Morgan, and Byne seem to have been abiding by. There was no pretense of buying the monastic buildings (the cloister, chapter house, and refectory) in order to save and preserve them (sometimes this is the motivation cited when a country appropriates the cultural heritage objects of another—one well-known example is the case of the Elgin Marbles from the Parthenon).

An offer amount of $35,000 for several components of the monastery was quickly extended by Byne on behalf of Hearst to the current owner, and just as quickly accepted. The idea was for these components to be adapted into part of Hearst’s ever-growing property in San Simeon (generally now known as Hearst Castle in California). The monastery’s church itself was not purchased and remains in-situ (in place), however, the thirteenth-century cloister (covered walkway), chapter house (meeting space) and other outbuildings were purchased by Hearst—and subsequently, slowly, removed.

Numerous letters from Byne to Morgan and Hearst reveal the politics involved in taking apart the cloister and other portions of the monastery. Numerous bribes were offered to keep the removal from being stopped by the government. The project was frequently threatened by the Spanish minister of fine arts; the sale was, in fact, illegal and the press had gotten a hold of the story. Despite this, the minister did not make good on his threats, so the project carried on.

Medieval Spain comes to the United States—in pieces

Taking the buildings of the monastery apart would have been a time-consuming process under any circumstances. It was soon realized the timing would not allow the cloister to be incorporated into the fabric of Hearst Castle—but another solution was at hand—a plan was made to have the monastery’s cloister function as a stand-alone museum.

Supervision of the dismantling of the monastery at Sacramenia was said to be meticulous—each block was carefully numbered, and extensive drawings made. It was a labor-intensive project that required significant problem solving along the way: weather, the logistics of moving the stones, and politics all came into play.

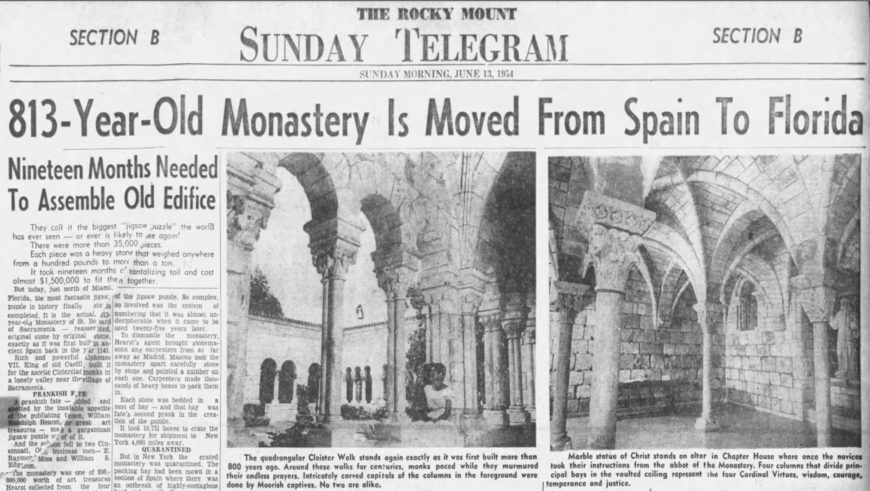

Eventually 11,000 crates would be shipped off to the United States. Unfortunately, the crates were not transported before an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease hit the Segovia area, causing the shipment to be quarantined upon its arrival on the east coast of the United States. The crates were opened in order to burn the potentially infectious hay with which the stones had been packed and in the process. Stones were heaved haphazardly into any crate that happened to be handy, spoiling the system of how the stones were to be put back into place.

By now, several years had passed since the purchase and Hearst’s finances had taken a beating in the stock market crash of 1929 (not that this stopped him from collecting European art and antiques) and the materials that had once formed the monastic buildings at Sacramenia were placed on the back burner. Once out of quarantine, the crates and their stones were left to decay in one of Hearst’s warehouses in Brooklyn, New York. The remains of the monastery lingered there for almost thirty more years.

In the 1940s, Raymond Moss and William Edgemon approached Hearst to purchase the Sacramenia remains, but he refused their offers. When he died, however, the estate was willing to sell to the pair who planned to use the stones to build a tourist attraction in Florida. The reconstruction of the Sacramenia stones was overseen by Allen Carswell (who also oversaw the rebuilding of the Cloisters Museum, a satellite of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan).

It took nineteen months and a tremendous amount of money to finish the bulk of the project. Carswell had a crew of eight stonemasons working under him. The rebuilding was criticized for its clumsy stereometry (the science of cutting stone precisely, which the medieval mason did via simple tools and tremendous skill) and the use of concrete in the reconstruction (a material not used by medieval builders).

Moss and Edgemon never intended to recreate what had once been in Spain. They dubbed their tourist attraction the “Ancient Spanish Monastery,” a misnomer still used in the present, and welcomed visitors to “Step back in time 800 years!” Sadly, for Moss and Edgemon, the tourist spot they had fought so hard to create did not entice visitors; bankrupt, they had to sell.

Today the transported parts of the Saint Bernard de Clairvaux monastery function as both an Episcopal Church and a tourist attraction—complete with a gift shop. People consider it a fascinating secret retreat outside Miami, “the perfect place to relax and enjoy the Miami sun with a European flair.”

If at first you don’t succeed…

Hearst, seeing the Sacramenia project as now a hopeless jigsaw puzzle (in fact Time magazine dubbed the situation “The Biggest Jigsaw in History” in a 1953 issue), hit the pause button on monastery acquisitions for a couple of years. But Hearst decided what any tycoon might—even in the face of the Great Depression—it was time to buy another monastery. This go-round he had plans for it to grace a “cabin” he was building in the remote wilderness of northern California, near Mount Shasta, on the McCloud River: his Wyntoon Estate. Hearst was making plans to create something that would make his San Simeon estate pale in comparison. The intended use was similar to that of the Sacramenia monastery—the stones were to be used to create a museum to house Hearst’s collection of medieval armor and other medieval objects, and Hearst had some other ideas as well.

Hearst contacted his associate Arthur Byne once again and put him back on the hunt. If Byne was a little warier this time around, who could blame him? He had seen how difficult the first endeavor was, and he was now dealing with a client who was cash poor. Hearst had not escaped the stock market crash unscathed but chose to ignore the fact.

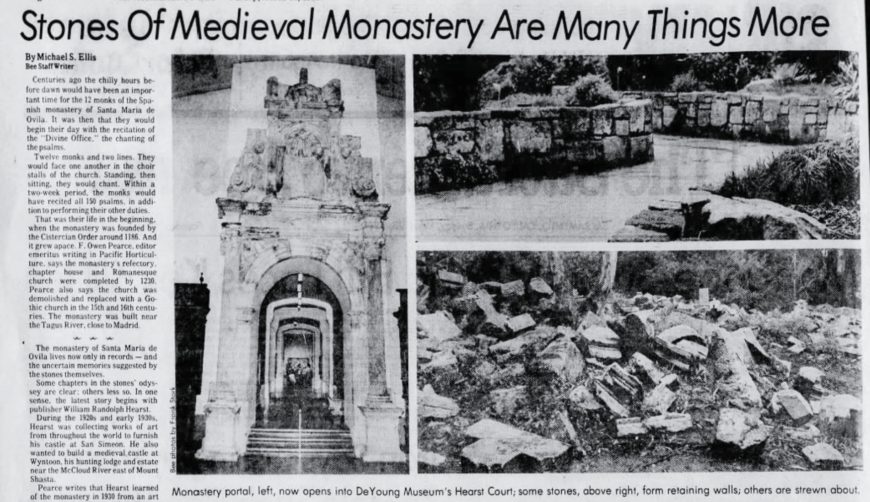

Nonetheless, Byne went on his mission and before long he found the ruins of the Santa María de Óvila Monastery in the Guadalajara province in Spain—another defunct Cistercian abbey in a remote locale. Though built later, this abbey was in a far worse condition than the monastery at Sacramenia. The Óvila abbey had suffered from the War of Spanish Succession and the Peninsular War. In the 1830s, the remaining four monks and one lay brother were ousted from the abbey when it lost the support of both the locals and the kingdom.

When Byne stumbled upon the monastery, it was owned by a farmer who used many of the buildings to house livestock; the chapter house was used for manure storage. But Byne saw potential, despite the dilapidation, manure, and overgrown vegetation. With Hearst’s approval, he purchased the majority of the complex. The plan was to remove many of the same elements as at Saint Bernard de Clairvaux: cloister, chapter house, and refectory. But at Santa María de Óvila, the main chapel was also purchased. The vision for the chapel, when rebuilt at Wyntoon, was to have it contain a 150-foot-long swimming pool. There would be a lounge in one side chapel, and a ladies changing area in the other—and the piece de resistance, a diving board in the apse (traditionally, an apse is a semi-circular area at the east end of a church that contains the altar).

Again, a painful process began to remove the stones from where they had stood so long. Byne wrote Hearst nearly daily, imploring Hearst to pay his bills or Byne would need to quit. Grudgingly, a check would appear to keep the project going, but the money was gone almost as soon as it was deposited. More than one hundred workers had to be paid, extensive equipment needed to be paid off, and the factory producing the crates for the stones could barely keep up with the demand—especially without cash in hand.

The removal of the Santa María de Óvila was illegal, just as Sacramenia before it. The new Spanish government (the Second Spanish Republic) stepped in—literally. A group of soldiers arrived and told Byne the deal was off. However, Byne was able to convince them to let the dismantling continue. Lucky for Hearst, and with the new government already off to a shaky start, the Óvila monastery was forgotten for a time. But Byne knew the clock was ticking and carried out the dismantling as quickly as possible. A local doctor had been trying for several years to convince the government to preserve the monastery finally succeeded in his efforts and in June of 1931 and the monastery was declared a national monument. Alas, it was too late. By this point Óvila had been almost fully dismantled, and within a month the stones were sailing towards the California coast.

The stones arrived at the San Francisco Harbor later that same year. Hearst found himself once more with thousands of stones, this time on the West Coast and finally faced the fact that he was broke. Ludicrous pillaging of medieval structures takes its toll on the pocket book (these two monasteries were not the only medieval acquisitions he made). The initial estimate for the new Wyntoon estate rolled in at $50,000,000; Hearst’s vision for an elaborate castle by the river was not going to happen. The dismantled monastery had arrived, but neither Hearst nor anyone else had any use for it. In this case, Hearst didn’t even have his own warehouse to store the stones in. They sat instead in a costly rented storage space near Fisherman’s wharf, taking up 28,000 square feet of space. Hearst now owned two dismantled monasteries on either coast that were both hopeless puzzles.

By 1940, Hearst was ready to give the stones away, and he had an interested party. By this time, the Spanish Civil War had occurred, and Francisco Franco was in power. Franco wanted the stones returned to Spain, but Hearst wasn’t interested. After considering various possibilities, Hearst was convinced to give the stones to the city of San Francisco in return for a tax abatement and forgiveness on his large storage bill. There was a stipulation that the stones would be used to create a medieval museum in Golden Gate Park. World War II intervened and no less than five fires occurred where the stones were now being kept in the park. Almost half of the stones were severely damaged, making them unsound for any kind of large-scale building project. The original numbering system that had been applied in order to place the tones accurately had melted off. Interest in the project evaporated and no museum was built.

A doorway from Óvila was reconstructed for an entrance at the de Young Museum in San Francisco (the doorway as part of the last additions to the Óvila monastery and dates from the Renaissance era). But the majority of the disassembled buildings, like those of its elder compatriot, was left in boxes to decay. Most of the stones were now kept in a warehouse at the de Young Museum; however, a good chunk remained in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. They were considered debris until some innovative gardeners used them in a variety of ornamental ways. A number of Óvila’s stones remain there to this day.

The Sacred Stones Project

In the 1990s, Abbot Thomas of New Clairvaux Abbey in Northern California began to petition San Francisco for the sale of the stones. It took almost a decade and much patience, but Abbot Thomas did succeed in his goal. This was the beginning of the Sacred Stones project, which planned to use the Santa María de Óvila stones for a new chapter house at the abbey of New Clairvaux in Vina, California. By this time, vast technological advances made precision much easier in terms of stereometry. Parts of the reconstruction involved sawing the now extremely weathered stones with a stone saw, then chiseling in an attempt to use the old techniques and thus make the building more authentic. Also, a hydraulic mortar was used (Cistercians built with ashlar masonry, which requires no mortar, just compression and finely cut and fitted stones). A steel framework topped things off, leaving the current building twice as strong as it was in the Middle Ages, and earthquake ready.

The abbey in Vina, California hired a master stonemason and several other skilled masons. Vast amounts of time were spent researching the project, mainly by Margaret Burke, an art historian. Burke made the call that—of all the abbey components brought over—only the chapter house was capable of being rebuilt with any kind of verisimilitude.