4.5: Islam

- Page ID

- 236847

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

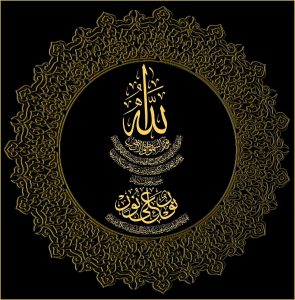

Islam is an Arabic word which means “submit.” Islam is described as being a way of living one’s life that is centered around submitting to God’s will and plan. A Muslim is one who attempts to live their life according to the ideas that God has made plain in the Qur’an, the revelation from God to Muhammad, the final prophet. The Arabic word for God is Allah, and Muslim people in all cultures and in all languages still use the Arabic to identify and call on their divine.

Like the other Abrahamic traditions, Christianity and Judaism, Islam originated in the Middle East, but is now a global faith. There are more than one billion Muslims living all over the globe. According to Muslims, Allah’s final prophet and messenger was Muhammad, and Allah’s final word the Qur’an. Since the time of the Prophet Muhammad, communities of Muslims been following the path of Islam in many cultural contexts.

Try this!

Take this quiz from the Pew Research Center and test your knowledge of Islam. Once you have taken it, it will give you statistics comparing you to others in the US:

The beginnings

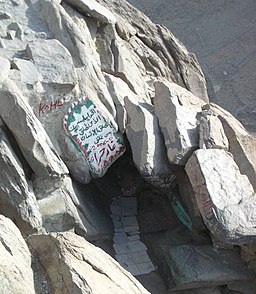

Born in the city of Mecca on the Arabian peninsula, a man named Muhammad was born in 570 CE to a powerful tribe, the Quraish, who were merchants. He was raised an orphan in his uncle’s house. He married an older woman, the widow Khadijah, for whom he had worked in the caravan trade as a merchant. Muhammad performed devotions each year on Mount Hira, outside of Mecca. The year he was 40 years old, he began a series of visions that would change his life, and change the world.

One year, Muhammad reported having a strange encounter during his devotions. The angle Gabriel, ((Jibra’il in Arabic)) commanded him, “Recite!” Twice Muhammad asked, “Recite what?” After he had asked this three times, the angel replied: “Read! In the name of your Lord who created: He created man from a clinging form. Read! Your Lord is the Most Bountiful One who taught by [means of] the pen, who taught man what he did not know.” (Qur’an, 96:1-5).

Muhammad felt “as though the words were written on [his] heart.” He ran down the mountain, but he heard a voice from the sky: “Muhammad, you are the Messenger of God, and I am Gabriel.”

From about 610CE until his death in 632CE, the Prophet Muhammad received the revelations first at Mecca and subsequently at Medina, to where he had emigrated in 622CE. The messages that he received warned of divine judgment and an invitation to return to the ways of the earlier prophets, including Abraham, Moses and Jesus. As he gained more followers, these revelations challenged his society. His world was polytheistic at the times, and the revelations to Muhammad spoke of the unity and oneness of the divine being. Meccan merchants were afraid that trade, which they believed was protected by the pagan gods, would suffer if polytheism was destroyed. Tribal feuds were a common part of the social structure, but the Prophet spoke of a universal community, or ummah. The revelation Muhammad received demanded social justice and reform: one should not only perform regular prayers, but also care for the poor and the weak.

As his message gained followers, Muhammad was threatened in Mecca. For a time, the influence and status of his wife Khadijah and his uncle, Abu Talib, the chief of the clan, protected Muhammad. After they died, however, Muhammad’s situation in Mecca changed.

The early Muslims encountered increasingly harsh persecution. In a forced flight in 622 CE, the Prophet and his followers emigrated north from Mecca to Medina. This event became known as the hijrah. The Prophet became the actual leader of all of Medina, establishing order and unity in the town. In 630 CE, after a series of military battles and negotiations with enemies in Mecca, Muhammad returned to the city with most of his followers. Many Meccans then embraced Islam, and the Prophet dedicated the Ka’bah, which had been a

place of pilgrimage even before the beginning of Islam, to the worship of the this one God. By the time of the Prophet’s death in 632 CE, much of the Arabian peninsula had embraced Islam.

When Muhammad died he had not named a successor to lead the Muslims as they expanded across Arabia and into Africa. One faction, the Shi’a, believed that only individuals directly descended from the Prophet could lead the Muslim community righteously. They thought that ‘Ali, Muhammad’s closest surviving blood male relative, should be their next leader. The other faction, the Sunnis, believed that the Prophet’s successor should be determined by a consensus of the followers, and so they successively elected three of his most trusted companions, commonly referred to as the Rightly Guided Caliphs (Abu Bakr, ‘Umar, and ‘Uthman), as leaders of the Muslim community; ‘Ali succeeded them as the fourth caliph.

Today Islam remains divided, largely, into Sunni and Shi’a branches. Sunnis revere all four caliphs, while Shi’as regard ‘Ali as the first caliph. The division between these two groups, based on their ideas about proper leadership for the people of Islam, has resulted in differences in worship as well as varied political and religious views. Sunnis are in the majority and occupy most of the Muslim world such as Syria, Egypt, Yemen and large majorities in southeast Asia, while Shi’a populations are concentrated in Iran and Iraq, with large numbers in Bahrain, Lebanon, Kuwait, Turkey, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

Key Takeaway

To quote Harvard’s Pluralism Project: “Most Muslims are careful to insist, however, that “Muhammad is no more than a messenger” (Qur’an 3:144), and not a divine being. When Muslims refer to the Prophet Muhammad, to show reverence, his name is often followed by the phrase “salla llahu alayhi wa sallam” meaning “May the prayers and peace of God be upon him.” In writing, this may be abbreviated as (sa), SAW, or PBUH meaning “peace be upon him,” while in other cases the calligraphic Arabic form is written.”

5 Pillars of Islam

The Five Pillars are the core beliefs and practices of Islam:

- Profession of Faith (shahada) The belief that “There is no god but God, and Muhammad is the Messenger of God” is central to Islam. Saying this once, with sincere conviction, is what makes one a Muslim.

- Prayer (salat) Prayers happens at least 5 times a day and specified times. This can be literally anywhere, as the belief is that holy space is created where one is when one prays. These prayers happen at dawn, noon, mid-afternoon, sunset, and after dark. Prayer includes a recitation of the opening chapter (sura) of the Qur’an, and is sometimes performed on a small rug or mat used expressly for this purpose.

- Alms (zakat) A fixed percentage of one’s excess income must be given to the poor and needy. This can be done in a variety of ways and for a variety of causes, ranging from feeding the poor to building a library. The rate of zakat is generally 2.5 percent of annual accumulated wealth, including savings and nonessential property.

- Fasting (sawm) Fasting happens during the daylight hours of the month of Ramadan. This includes abstaining from food, drink, and sex. During Ramadan they share the hunger and thirst of the needy as a reminder of the religious duty to help those less fortunate.

- Pilgrimage (hajj) At least once in the life of each Muslim whose health and finances permit , one is required to go to Mecca on hajj. The men then receive a title of Hajji, and women Hajja.

Exercise: watch a clip from National Geographic about the Hajj

Beliefs

Diverse traditions within Islam have different interpretations of the Qur’an, the Hadith (teachings of Prophet Muhammad), and views on designating leadership within Islam. The main branches of the tradition are: Sunni, Shi’a, and one that connects at times with both, the Sufi movement. All agree on most beliefs, but the differences in practice are real.

1. The Oneness of God

About Allah

2. Belief in Angels

Angels, “Malaikah” in Arabic, are beings made of light who make plain God’s commands and plan for humanity. Islam claims a function for a number of angels, including Mika’il, (known in the west as Michael), who is believed to guard places of worship and reward people’s good deeds. As the Angel of Mercy, he asks Allah to forgive people’s sins. It is believed that both the Angel Jibril and the Angel Mika’il will be present on the Day of Judgment. Another angel is Izra’il, also known as the Angel of Death, who takes the souls at the time of death,. Raqib and ‘Atid record the deeds of every person, both good and bad, and Munkar and Nakir will question the soul after death. The most important function however, is that of the archangel Jibril, (also known as Gabriel in the west), who conveyed God’s revelations to divinely chosen persons known as prophets.

The Messenger has believed in what was revealed to him from his Lord, and [so have] the believers. All of them have believed in Allah and His angels and His books and His messengers, [saying], ‘We make no distinctions between any of His messengers.’ And they say, ‘We hear and obey. [We seek] your forgiveness, our Lord, and to You is the [final] destination.’(Qur’an 2:285)

3. Divine Revelation

Allah is beyond being directly perceived by humans, so over time angels have conveyed the commands and desires of Allah to all of the prophets, and these prophets spread theses ideas and commands to the rest of humanity. Muslims believe that while Muhammad was given the Qur’an by Jibril, , previous prophets were also given revelations from God: the Scrolls to Abraham, the Torah to Moses, the Psalms to David, and the Gospel to Jesus. However, since the Qur’an is considered the final scripture and final words for all of humanity, it supersedes all previous revelations and writings until the Day of Resurrection. Memorizing parts or the entirety of the Qur’an is an activity that is encouraged and is common for most Muslims. Hafiz is a title in Islam, which is used for someone who has completely memorized the Qur’an.

4. Prophets and Messengers

Prophets are people who lived in many different centuries and were required to deliver God’s messages and commands to humanity. Muslims believe the prophets should be respected but never worshipped, however. There are twenty-five prophets explicitly mentioned in the Qur’an. These include Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, and Jesus. Muslims believe that while prophets are sinless human beings, they do not believe that any prophet share any aspect of divinity. Prophets are examples of how to put Allah’s teachings into practice. Muhammad is considered the final prophet, and it is held that he was sent to all of humanity for all times and places, and with him all revelation is complete.

5. Day of Judgement

According to Islam, every prophet came to warn their people about the impending Day of Judgment; the time in which a person’s deeds will be judged and they will be sent either to Paradise (jannah) or to Hell (jahannam). Hell is described as physical and spiritual suffering, while Paradise gives joy, comfort, and bliss. Entrance into Paradise earned by following the word given by prophets and living a pious and devout life, while an afterlife in Hell is warranted by rejecting Allah’s revelations and prophets, and living an immoral life. Paradise is ultimately given to human individuals based on Allah’s mercy – a person’s sins can be forgiven Allah decrees this, and no one enters Paradise except by Allah’s mercy . Forgiveness is key to this set of beliefs, and Muslims are encouraged to repent and ask for forgiveness for their sins.

6. Divine Decree

Judgement Day is based on a key belief that all people have been given free will. To some extent, this contradicts the idea that Allah is all-knowing, including knowing each person’s destiny in the afterlife. Allah is believed to be just in all judgment and will do what is considered right for each person at the time of judgment. Each person will be judged according to the free choices they have made. Allah will know all the choices a person might make, however. The contradiction between a belief in free will and in stating that Allah knows and predicts all is generally settled in the phrases like “insha-Allah” (God-willing), and “masha-Allah” (God willed it).

“The Lord has created and balanced all things and has fixed their destinies and guided them”. (Qur’an 87:2)

While Shi’a Muslims generally agree with Sunnis in the aforementioned beliefs, they differ primarily by the inclusion of the doctrine of Imamate.

Imamate

Though the Prophet Muhammad died, Shi’as do not believe this means humans were left without a guide or leadership after his death. The Imams, a group of individuals descended from the Prophet Muhammad’s family, are those leaders. They show how to live Allah’s teachings. There were 12 Imams in sequence after the death of Muhammad. Although the twelfth Imam died long ago, it is believed that he still guides people and will come again at the End of Times to restore peace and justice to the world. For Zaydi Shi’as, these were five individuals, not twelve, and their leadership has continued with successive rulers. For Isma’ili Shi’as, the Nizari branch holds that the Imams have continued up until the present, with the current Imam referred to as the “Imam of the Time”. Beliefs about the character, role and functions of the Imams change with the various branches of the Shi’as.

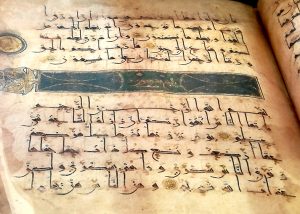

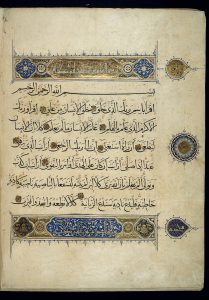

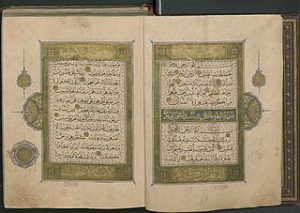

The Qur’an

Islam’s main sacred text is the Qur’an. According to Muslim tradition the Qur’an is the actual word of God revealed to the Prophet Muhammad in the Arabic language through the intermediary of the Archangel Jibril (Gabriel).

The Qur’an consists of 114 surahs, or chapters. The text is traditionally read aloud, as Muhammad was instructed in the first revelation he received: ‘Recite in the name of your Lord’ (Surah 96. 1). The word Qur’an comes from the Arabic verb meaning ‘to read’.

After Muhammad’s death, his secretary, Zayd ibn Thabit, compiled the revelation into a book, and the text was later collated and definitively codified by order of Caliph ‘Uthman in 651CE . This is the text used in all Qur’an manuscripts, although the styles of calligraphy and illumination depend on the place and date of production.

The Qur’an, the central scripture of Islam, begins with al-Fatihah, literally “the Opening”:

In the name of God, The Lord of Mercy, The Giver of Mercy!

Praise belongs to God, Lord of the Worlds,

The Lord of Mercy, the Giver of Mercy,

Master of the Day of Judgment.

It is You we worship; it is You we ask for help.

Guide us to the straight path:

The path of those You have blessed

those who incur no anger

and who have not gone astray.

With help from Mustafa Shah[1], we consider the Qur’an in more detail:

Preserved in the language of Arabic, the Qur’an is Islam’s sacred text. It is believed that the Qur’an enshrines the literal word of God. With its unique composition and style, the Qur’an is also considered the pre-eminent literary masterpiece of the Arabic language and one of the earliest extant Arabic literary sources. Its contents, which focus on the theme of God’s unity of being and his transcendence, provide the foundations of the beliefs of Islam. Emphasizing the theme of continuation, the Qur’an does not present its teachings as representing a new religion, but rather the revivification of an ancient monotheistic tradition of faith which shares the same spiritual legacy with Judaism and Christianity.

The Islamic literary sources intimate that at the age of forty, while secluded in a cave on the outskirts of Mecca, the very first verses of the Qur’an were revealed to Muhammad by the Archangel Gabriel, thus marking the beginning of his call to prophethood.

Recite in the Name of your Lord who created;

Created man from a congealed clot of blood;

Recite and indeed your Lord is most merciful;

He who taught by the pen;

Taught man what he knew not.

According to Muslim literary sources, when the Prophet passed away in 632 CE the Qur’an did not formally exist as a fixed text but was ‘written down on palm-leaf stalks, scattered parchments, shoulder blades, limestone and memorized in the hearts of men’. During the rule of one of Muhammad’s later successors, the caliph Uthman (r. 644–656 CE), a standardized copy of the Qur’an was compiled and distributed to the main centers of the Islamic Empire. Although the caliph’s original codices have not survived, his introduction of a

fixed text is recognized as one of his enduring achievements. One of the oldest copies of the Qur’an, which is dated to the 8th century, is held in the British Library; it includes over two-thirds of the complete text.

The traditional view is that the Qur’an’s contents were revealed piecemeal. Revelation identified with the early Meccan years focused primarily on the accentuation of God’s unity and transcendence. Early Qur’anic revelation includes declarations about the omnipotence and omniscience of God, the resurrection of the dead, the impending Day of Judgement and rewards and punishment in the hereafter. The theme of personal morality and piety is also promoted, while polytheism and idolatry are condemned. The imposition of a detailed system of ritual practices and laws occurs in the post-Hijrah period, while the people were in Medina. Set times for prayer, fasting, the giving of alms, and the performance of pilgrimage were made obligatory by the Qur’an at Medina. A range of legal measures was introduced, including rules for inheritance and dietary guidelines, the proscription of usury, laws on marriage and divorce and a penal code.

The requisite practice of committing the whole text to memory has an extended history, and still forms an integral part of the curriculum followed in seminaries throughout the Islamic world. The preservation and study of the Qur’an led to the flourishing of literary traditions of learning, including grammar, philology and even poetry, as scholars used insights from such scholarship to interpret the Qur’an.

Hafiz literally meaning “guardian” or “memorizer”, depending on the context, is a term used by Muslims for someone who has completely memorized the Quran

Definition of hafiz

In the Qur’an, Muhammad is designated as being the final prophet sent to mankind and is hailed as being one of a distinguished line of divinely appointed messengers who were sent to proclaim the message of God’s unity. It states:

Indeed, those who believe, the Jews, the Christians, and the

Sabians – all those who acknowledge God and the Last Day and

perform good works – will be granted their rewards with their Lord.

Fear shall not affect them, nor shall they grieve (Q. 2.62)

Confirming the shared spiritual heritage with Judaism and Christianity, the tribulations and triumphs of biblical personalities are also portrayed in the narratives of the Qur’an. Teachings on Jesus emphasize his human nature, although the Qur’an upholds the notion of his immaculate conception and the miracles he performed. However, it rejects the claim that Jesus was the Son of God and also the concept of the divine Trinity; the Qur’an also denies the Crucifixion. Jesus is lauded as a prophet to the Children of Israel, and his mother Mary is held in great esteem, even having a chapter of the Qur’an named after her. It is significant to note that in deference to the sacred status of their revealed scripture, the Qur’an describes Jews and Christians as being ‘the People of the Book’.

Exercise: watch this!

Watch this video from the British Library on the Qur’an

Growth

Over the centuries, after the death of the Prophet Muhammad, Islam was spread throughout the Middle East, Northern Africa, into Asia, and beyond. Some of the spread was peaceful and associated with trade and scholarship, art and architecture. Some of the spread of Islam came along with the conquering of lands and other tribes.

Muslim rulers, soldiers, traders, mystics, scholars, poets and architects all contributed to the shaping of distinctive Islamic cultures. Across the expanding Islamic world, religious beliefs began to blend with various cultures and traditions to produce local versions of Islam. Not all ritual and practice was the same from place to place, although the stated beliefs carried through. Various dynasties of powerful families rose, and as they converted to Islam, their tribes or countries converted with them. Trade and the travel of scholars had a large influence on the expansion of the faith.

These two brief videos (each about 8 minutes) will give you a map and some indications of where, when, and how the religion spread. Because it was both a spiritual as well as political expansion, you can often see differences in how things happened and how local populations responded to the new Islamic Empire.

Key Takeaway: The Context for the development of Islam–Khan Academy

Key Takeaway: The Spread of Islamic Culture

According to the Harvard Pluralism Project:

Under each of these empires, transregional Islamic culture mixed with local traditions to produce distinctive forms of statecraft, theology, art, architecture, and science. Further, many scholars argue that the European Renaissance would not have been possible without the creativity and myriad achievements of Muslim scholars, thinkers, and civilizations.

“Basic Beliefs of Islam – God.” Basic Beliefs of Islam: God, University of Nottingham, England, 26 Jan. 2016, youtu.be/05b1BwNvqCk.

“Islamic Beliefs.” The Pluralism Project, Harvard University, 2021, pluralism.org/islamic-beliefs.

“Muhammad: The Messenger of God.” The Pluralism Project, Harvard University, 2021, pluralism.org/muhammad-the-messenger-of-god.

Shah, Mustafa. “The Qur’an.” British Library: Discovering Sacred Texts, 2019, www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/the-quran.

“Qur’an: The Word of God.” The Pluralism Project, Harvard University, 2021, pluralism.org/qur%E2%80%99an-the-word-of-god.

“Discovering Sacred Texts: Islam.” Discovering Sacred Texts, British Library, 2 Oct. 2019, youtu.be/2_CDBv6CICc.

“Islam Introduction.” British Library, Discovering Sacred Texts: Islam, 2019, www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/islam-introduction.

“Spread of Islamic CULTURE: World History: Khan Academy.” Khan Academy, 26 Apr. 2017, youtu.be/sDSTgKIQAzE.

“Contextualization–Islam | World History | Khan Academy.” Khan Academy, 16 June 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=gB7ya6386iA.

- Mustafa Shah is a Senior Lecturer in Islamic Studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). His principal research interests include classical Qurʾanic commentary, ḥadith scholarship, classical theology and Arabic linguistic thought. Among his publications is the collection of articles devoted to Qur’anic exegesis: Tafsīr: Interpreting the Qur’an (Routledge, 2013). He is also joint editor of the Oxford Handbook of Qur’anic Studies (OUP 2019). ↵