4.3: Christianity

- Page ID

- 236845

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Christianity

In the beginning of the movement that became Christianity, the earliest followers were not actually “Christians”. They were Jewish, loyal followers of the rabbi Jesus, and, especially at the very beginning of the movement, were focused on reforming Judaism. They talked to anyone who would listen, instructing their fellow Jews on the ideas taught by Jesus, this itinerant rabbi whom they eventually came to believe was the longed for messiah from numerous Hebrew prophecies.

Jesus was born in Palestine about 4 BCE.[1] He lived life as a Jew, in northern Judea, which had been conquered and was occupied by the Roman Empire. His teaching ministry was, at most, three years long. Jesus was thought to be in his thirties when he was put to death by crucifixion, a commonly used Roman style of execution of serious criminals. His followers said that they found his tomb empty three days after the execution. It is said that Jesus was resurrected from the dead and that he appeared before the disciples and followers, ate and talked with them, and proclaimed the kingdom of God to them before ascending to heaven.

Jesus did not write his message down in any way during his lifetime, nor did others who were immediate followers write about him during his ministry. Written materials started emerging in letters and gospels about 25-30 years after his lifetime.

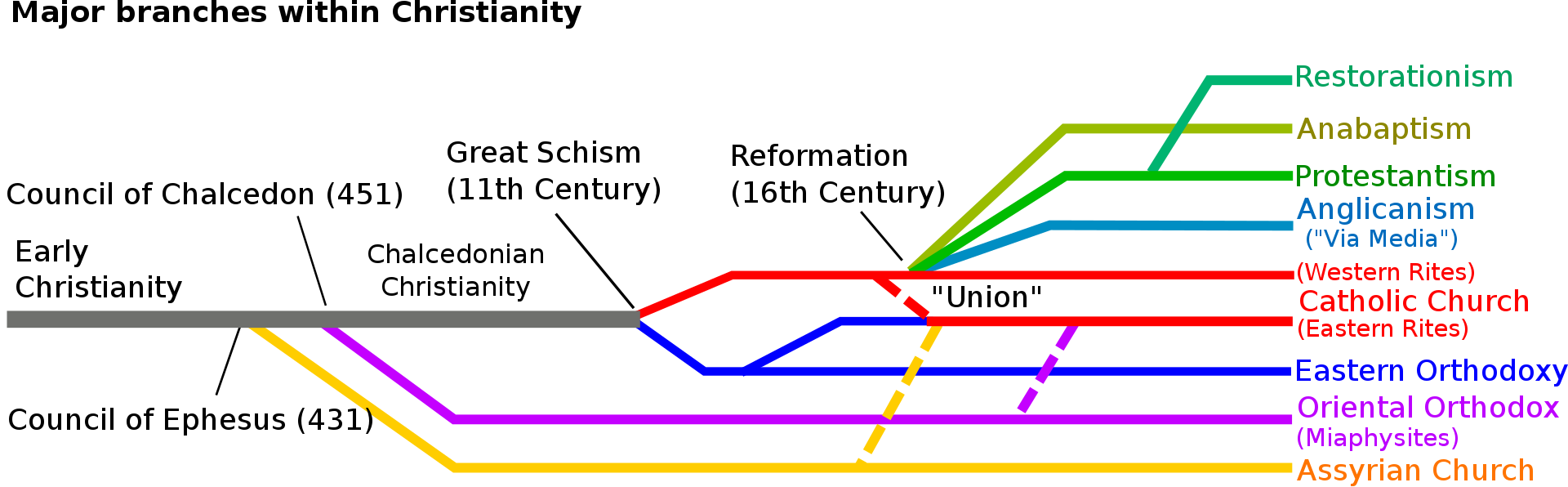

Today Christianity has three major divisions, each possessing its own branches: the Catholic Church, Orthodox Christian churches, and Protestant churches. Within this broad framework, created by disagreement over tradition, belief and belief, are contained literally hundreds of smaller groups.

Learning Object

A quick and slightly tongue in cheek summary of some of the following content:

The Ministry

Christianity is centered on the person of Jesus. He was alive during a time of great religious and political unrest in Israel, which was a country that had been conquered (yet again!) and was under Roman rule. Many Jews believed that they were living in the “end times” and so expected God to intervene on their behalf, which would include the appearance of a political leader called the Messiah.

Jesus was a teacher and preacher, talking to people along the road, in groups in a field or on a hill or beside a lake. He talked in parables, which are small stories that make a point, a bit like Aesop’s fables or other stories–short, moral, and instructive. He is said to perform miracles of healing, of transformation and even of returning people from death to life.

The Messianic prophecies had suggested that they could expect a new King David, a warrior, but also a devout follower of the Jewish faith. Jesus was not quite like this–certainly not a warrior, nor a rebel, nor a military leader.

After his very brief teaching ministry, Jesus was arrested in Jerusalem at Passover time by authorities who considered him a heretic, and even a threat to the tentative peace that the leaders tried to maintain with the Romans. He was soon tried by Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Israel at that time, and was executed by crucifixion by the Romans. Three days after he was killed, his followers found an empty tomb. Other followers reported appearances and visitations by a transformed Jesus who had been resurrected from the dead.

Christian scriptures say that forty days after finding the empty tomb, Jesus ascended to the heavens, promising to return again.

The content of the preaching from Jesus and his followers focused on the “great commandment” to love one’s neighbor as oneself. “Neighbor” is defined not just as the person living next door, but as including all people, especially the poor, the needy, the outcast, the foreigner, the unloved and societally outcast. He warned people to remember their own flaws before judging others and invited those who were completely without sin to “cast the first stone”, referring to a practice of that era of stoning prostitutes. This acceptance of all into the Kingdom of God was not popular with the rich or elite or the powerful religious leaders, but offered hope to those who felt shunned by their religion, their society, their country. The preaching of a Kingdom of God offered to all was a departure from traditional religious teaching at the time.

The Writings

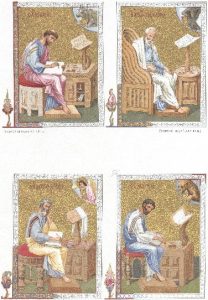

Virtually all we know of Jesus comes by way of the four Biblical Gospels, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John in the Christian New Testament. These four accounts describe the life and teachings of Jesus. The four portraits of Jesus were recorded some time after his death, with estimates of dates of writing being between 65-100 AD, more than a generation after the death of Jesus. Each gospel reflects the distinctive viewpoints and culture of the individual writers. Jesus is portrayed as a Jew accepting the practices and authority of his Jewish tradition, preaching from the prophets and writings of the Hebrew Scriptures. Jesus centers his teaching on the subject of the Kingdom of God. He emphasizes love for God and love and compassion for other people. He recommends not judging others, giving help to the needy and oppressed, offering forgiveness, and practicing nonviolence. The writers turned oral stories and teachings into written materials in the genre called a gospel.

Originally there were many gospels, few of which were included in the Bible. We know of some of these gospels that did not become part of the canon (the accepted authoritative list of Biblical books) , such as the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Mary, the Gospel of Peter, various infancy Gospels, some gospels mentioned by early church writers that no longer exist in any written format, gospels from the Gnostics, and fragments of many more. What we can actually know about the ministry and person of Jesus and his followers is limited to what writers created from oral transmission, and that still exist in some form today.

The small group of Jesus’ followers were inspired to travel and create communities of believers throughout the Mediterranean world and, eventually, throughout the rest of the world. It was in Antioch, now in Turkey, that they were first called “Christians”. Some of the traveling preachers wrote encouragement, instruction and correction to a number of these small congregations, and these letters, which are found in

the Christians scriptures under the genre of Epistle, are considered the earliest indications of the movement that would come to be called the Christian church. A man named Paul wrote many of the letters, but some of the letters are titled but unattributed, and some bear the name of someone else who was well known in the early churches. These were likely not actually written by that leader, but just written under those important names, to lend authority to the messages contained within.

Paul is largely responsible for the spread of belief in Jesus as messiah beyond the Jewish world through his extensive travels and powerful letters. Because of Paul’s leadership, the early church finally decided that converts to the Christian faith did not have to observe Jewish religious laws. Gentiles were then accepted as believers in the communities around the Mediterranean.

In Paul’s view, a right relationship with God came only through faith in Jesus. Following moral rules was done willingly out of gratitude for what God had accomplished through Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross. Essentially, Paul’s views on the meaning of Jesus, morality, and Christian practice became the norm for most of the Christian world. Paul’s ideas are still sometimes preached more frequently than those of Jesus.

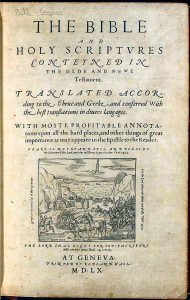

With help from Scott McKendrick[2], we see some of the history and content of the Christian Bible. Christians use both the Hebrew Scriptures (which they call the Old Testament, as opposed to the Jewish term Tanakh for these writings) and the writings of the first and early second century church leaders, called the New Testament.

The Christian Bible has had a long and complex genesis. The term ‘bible’ is derived from the Greek word βιβλία (books), which in turn is based on the Greek word for papyrus (βύβλος or βίβλος). (Throughout antiquity papyrus was the principal material from which books were made.) As reflected in its name, the Christian Bible is a book made up of many books, incorporating a large number of Jewish scriptures as its first section, known as the Old Testament (derived from the Latin word testamentum, in the sense of dispensation or covenant), and a smaller corpus of Christian texts as its second section, the New Testament. Although the Christian Church regards both Testaments as inspired, it also holds as a fundamental doctrine that the New Testament bears witness to the fulfilment of the Old.

Early Christians adopted a Greek version of the Jewish scriptures that had been produced for Jews residing in Egypt and other Greek-speaking territories, who were less familiar with Hebrew. Known as the Septuagint (‘seventy’ in Latin), this translation was traditionally attributed to seventy or so scholars working in Alexandria for Ptolemy II Philadephus (308–246 CE). The Septuagint has at its heart the three key elements of Jewish scripture. The first, the Torah, is traditionally ascribed to Moses and comprises the five books from Genesis to Deuteronomy. The second is the twenty-one books of the Prophets, including the twelve Minor Prophets. The third, the Writings, comprises thirteen assorted books: the Psalms, Proverbs, Job, the Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah and Chronicles 1–2. The shaping of these thirty-nine books had evolved over nearly a millennium.

The Septuagint also contains several texts that are excluded from the canon of Jewish scripture, most notably Tobit, Judith, the Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus (Sirach), Baruch and the two books of Maccabees. These texts were thus accepted by early Christians, who developed their canon based on the Greek rather than the Hebrew version of the Jewish scriptures. When St Jerome (c. 342–420 CE) undertook the translation of the Bible into Latin, he advocated that the Church follow the Jewish canon, and designated these extra texts as Apocrypha (from ἀπόκρυφος, hidden). Because the Protestant reformers of the 16th century used copies of the Jewish Hebrew canon of Scripture as the basis for their translations, these texts either do not form part of Protestant Bibles, or are included in them separately as apocrypha or deuterocanonical books (from the Greek word δεύτερος, or second canon). The apocrypha do, however, remain part of Roman Catholic and Orthodox Bibles.

Whereas their opinions differ over the Old Testament, Protestants, Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox Christians all accept the same New Testament canon. This was formed over a much shorter period than the Jewish scriptures, but similarly comprises several distinct texts. The core of the New Testament is the Four Gospels. The word ‘gospel’ is possibly derived from the Old English translation of the Latin word evangelium, which is itself based on the Greek εὐαγγέλιον (good news) and is the origin of the term for the authors of these texts, the Evangelists. The Four Gospels of Sts Matthew, Mark, Luke and John were widely accepted as uniquely authoritative from an early date.

The other twenty-three books of the New Testament include the Acts of the Apostles, in which St Luke recounts the life of the Church immediately after Jesus’s ascension, letters to early Christian communities or individuals written by the Apostle Paul and other early Christian leaders, and an apocalyptic account, or revelation, traditionally attributed to St John. Although the core of the New Testament canon, the Four Gospels and thirteen Epistles of St Paul, was established by the middle of the 2nd century, the full canon of twenty-seven books was formally confirmed only during the 4th century CE. Until then, some books, such as Hebrews and Revelation, were in doubt, and other texts, such as the Epistle of Barnabas and Shepherd of Hermas, were considered authoritative by some Christians. All of the books of the New Testament were originally written in Greek, the language of the predominant literate community in the region, to further the evangelizing purpose of the New Testament.

The Creeds

One feature found in most of Christianity is its emphasis on a creed, a summary statement of faith. The earliest creeds were the Apostle’s Creed and the Nicene Creed, both of which were eventually validated by councils of church leaders.

THE NICENE CREED

I believe in one God, the Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth and of all things visible and

invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all ages, God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten not made, being of one substance with the Father, through Whom all things were made: Who for us men and for our salvation came down from heaven, was incarnate by the Holy Spirit of the virgin Mary, and was made man: Who for us, too, was crucified under Pontius Pilate, suffered, and was buried: the third day He rose according to the Scriptures, ascended into heaven, and is seated on the right hand of the Father: He shall come again with glory to judge the living and the dead, and His kingdom shall have no end. And in the Holy Spirit, the Lord and Giver of life, Who proceeds from the Father and the Son: Who together with the Father and the Son is worshiped and glorified: Who spoke by the prophets. And I believe one holy, Christian, and apostolic Church. I acknowledge one baptism for the remission of sins, and I look for the resurrection of the dead and life of the age to come.

Amen.

The Council of Nicaea, held in 325 CE, was the most important of these early church councils. In some groups (understandable given the amount of time that had passed since the life of Jesus) some believers had proposed that Jesus Christ was not really human at all, but was God appearing to be human, while others had proposed that he was only a human being. The early church rejected both of these views as it worked together to articulate a consistent expression of faith for all followers: that Jesus Christ was both fully God and fully human. The concept of Incarnation was solidified–that God took on human flesh in the person of Jesus, who was born of a virgin girl called Mary.

Key Takeaway: From the Harvard Pluralism Project/Christianity

“The Latin term credo is often translated today as “I believe…” but it is important to remember that its literal meaning is “I give my heart…” It is language of the heart, a profound expression of commitment, not simply a list of statements to which one gives intellectual assent. When the early church was being persecuted, commitment to the way of Christ was often dangerous, requiring true courage.”

Creeds came into use during the ritual of baptism. Baptisms had been performed in Judaism as a rite of cleansing and renewal, and could happen more than once. In the early Christian tradition, a person would put on new white clothing, and become a Christian by a ritual immersion in water, often a running river or stream, and their affirmation of commitment to the Christian beliefs. Christian baptism is a one time event.

Among the oldest creeds of the Christian church is the Apostles’ Creed, formed from questions that were began to be composed about 150 CE and were used ritually at the time of Christian baptism.

THE APOSTLES CREED

I believe in God the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth. And in Jesus Christ, His only Son, our Lord; Who was conceived by the Holy Spirit; Born of the Virgin Mary; Suffered under Pontius Pilate; Was crucified, dead and buried; He descended into Hell; The third day He rose again from the dead; He ascended into heaven; And sitteth on the right hand of God the Father Almighty; From thence He shall come to judge the living and the dead. I believe in the Holy Spirit; The Holy Christian Church, the Communion of Saints; The Forgiveness of sins; The Resurrection of the body; And the life everlasting. Amen.

The Apostle’s Creed came to its final form in southwestern France in the early 7th century CE. This creed had, through its series of questions, replaced other baptismal liturgies and was finally acknowledged as the official statement of faith of the entire Catholic church in the West in the early 13th century CE. As well as the Catholic church, the creedal Protestant churches accept the Apostles’ Creed and use it in worship. (Some churches delete the line “He descended into Hell.”) Not all Protestant churches use creeds. Some use what are called Professions of Faith, and some are called Covenantal churches, expressing their ideas in simpler expressions of faith.

Beliefs

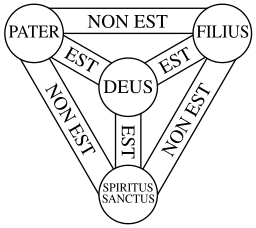

The Christian theology took many centuries to be fully worked out through discussions, controversies, and great councils that produced the central creeds of the faith. One vital idea developed is that of the Trinity, which is the belief that God, although one, is three “persons.” The Father is the guiding intelligence that created the universe and made human beings an important part of the divine plan. The Son is Jesus Christ, who has both a fully human and a fully divine nature united in one person. His presence in the world is called the Incarnation of the divine. The Holy Spirit is the power of God that guides all believers.

Christians believe in life after death, a resurrection of all people, and a final judgment. Controversies over doctrine and church structure led to schisms in the church, which then produced the great branches of Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Protestant Christianity—with Protestantism itself subdividing many more times. Christian practice is rich, complex, and varied in beliefs and practices within the different branches.

All Christians practice baptism and observe the Lord’s Supper, with varying understandings of what each practice actually means. Holidays that mark significant times in the life of Christ and the early church, such as Easter and Christmas, are celebrated. Christianity has had a profound effect

All Christians practice baptism and observe the Lord’s Supper, with varying understandings of what each practice actually means. Holidays that mark significant times in the life of Christ and the early church, such as Easter and Christmas, are celebrated. Christianity has had a profound effect on the arts in the fields of architecture, painting, sculpture, and music. Its themes and stories are echoed in much great literature.

on the arts in the fields of architecture, painting, sculpture, and music. Its themes and stories are echoed in much great literature.

Now, people seem to think that Christians, at least at some point, all believed the same things and thought about their faith in the same ways. This has simply never been the case.

According to Wayne A. Meeks, Woolsey Professor of Biblical Studies at Yale University:

“The early Christians put a great emphasis upon unity amongst one another, and the odd thing is they seemed always to have been squabbling with one another over what kind of unity they were to have. The earliest documents we have are Paul’s letters and what do we find there? He is, ever and again, having defend himself against some other Christians who have come in and said, “No, Paul didn’t tell it right. We have now to tell you the real thing.” So, it is clear from the very beginning of Christianity, that there are different ways of interpreting the fundamental message. There are different kinds of practice; there are arguments over how Jewish are we to be; how Greek are we to be; how do we adapt to the surrounding culture – what is the real meaning of the death of Jesus, how important is the death of Jesus? Maybe it’s the sayings of Jesus that are really the important thing and not his death and not his resurrection.

Now, this runs very contrary to the view… which the mainstream Christianity has always quite understandably wanted to convey. That is, that at the beginning, everything was unity, everything was clear, everything was understandable and only gradually, under outside influences, heresies arose and conflict resulted, so that we must get back somehow to that Golden Age, when everything was okay.

One of the most difficult things which has emerged from modern historical scholarship, is precisely that that Golden Age eludes us. The harder we work to try to arrive at that first place where Christianity were all one and everything was clear, the more it… seems a will-o’- the-wisp. There never was this pure Christianity, different from everybody else and clear, in its contours….The notion of Orthodoxy, which is only the flip-side of the notion of heresy, [developed in the second century]. So heresy which… simply means [in Greek], a choice, and is most commonly used to talk about a philosophical school, now takes on a negative connotation for the Christians. [It] first of all implies a schismatic group, a choice, which is different from the mainstream,… and then secondarily, [implies] people have wrong ideas, people who think wrongly about this or that, notably about the identity of Jesus Christ. The other side of that, of course, is our side, which has orthodoxy, that is, right thinking. The great controversies of the 3rd, 4th and 5th centuries, which create what we will know as orthodoxy, and in the west, Catholicism, emerge from this very drive to create a a unified body of opinion.”

The Divisions

The three big branches of Christianity are Roman Catholicism, Orthodox Churches and Protestant Churches. Each has additional branches within, but these are the umbrella categories of Christians. (There are groups that don’t fit within these branches that also call themselves Christian, but the debate over their place in Christianity is ongoing.)

As Christianity moved away from Judea and the small house churches that developed early in the faith, and as centuries passed, belief and practices in the communities of faith began to differ according to location, history, and cultural ideals. Long-rising disagreements about belief and practice between the churches who looked to Rome for leadership and those Byzantine churches who looked to Constantinople (now called Istanbul) resulted in a split that divided the European Christian church into two major branches: the Western Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. This split is known as the Great Schism, or sometimes the “East-West Schism” or the “Schism of 1054 CE.”

The divide between East and West did not stop Christians from their disagreements, however. Many issues continued to cause deep concern and outrage, ranging from the power (and often corruption) of the clergy and the church in ordinary people’s lives, to the money taken by the church from the people, to the inability of ordinary people to read the Bible, and much more.

Although there were other early church reformers and group of protesters, it is generally held that the Protestant Reformation began in Wittenberg, Germany, on October 31, 1517.

On this day, Martin Luther, a teacher and a monk, published a document he called Disputation on the Power of Indulgences, or 95 Theses, and nailed them to the door of the cathedral there. The document was a series of 95 ideas about Christianity that he challenged the church to consider.

Following Luther at about the same time period came people such as John Calvin, William Tyndale, Huldrich Zwingli, John Knox, and many more. From this early start come Lutherans, Presbyterians, Baptists, Methodists, Congregationalists, and eventually groups like Quakers, Pentecostals, Evangelicals, and so forth. In the modern era, there are hundreds of Protestant denominations, split from original groups over belief, practice, style of worship, politics, dress, social issues, and much more.

Interesting data

There are some interesting statistics about Christians in various groups, across the globe. Check out this data from Pew Research about the various branches of Christianity:

Growth

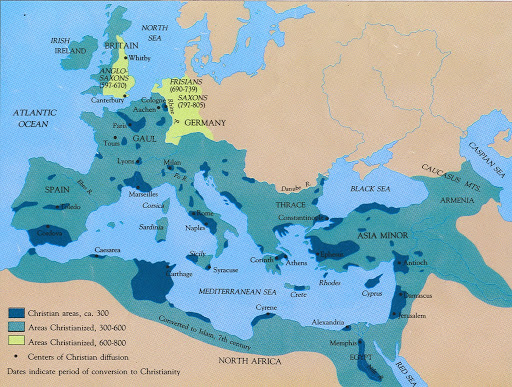

The spread of Christianity took place gradually, moving around the Mediterranean basin for the first decades, and gradually into mainland Europe. It is not, originally, a European movement, however. With a little help from Brian Stanley[3], we get some more history.

Christianity was not originally a western religion. It originated on the western fringe of Asia – what we tend to call the ‘Middle East’. However, for many centuries the expansion of Christianity into the rest of the world was directed from Europe and became entangled with the growth of the great European empires.

The earliest growth centered around the Mediterranean, both the African and European shores. With time, the messages of Christianity moved further inland, again into Africa and Europe, but also into Asia Minor. It was not until the 9th century CE that any major inroads in converting Scandinavia occurred, for example. (An excellent article with more detail about this process can be found at the National Museum of Denmark’s website–Christianity comes to Denmark)

The Christian Church has sent out missionaries from the days of the Apostle Paul down to the present day. In the 16th and 17th centuries CE many of them belonged to the Catholic religious orders – societies of men (and later women) who followed a strict rule of life and committed themselves to the task of spreading the faith. The Society of Jesus – or Jesuits – established by St. Ignatius of Loyola in 1534 was especially influential in China. Jesuit missionaries were also active in South America and in the ancient Kongo kingdom in West Africa. Although Latin remained the language of liturgy used in the Mass throughout the Roman Catholic Church until after the Second Vatican Council of 1962–65, some Catholic missionaries were quick to realize the importance of teaching the faith in the languages of the people to whom they were sent.

Our belief in the integrity and value of all human cultures is quite a recent development. From the early 20th century, anthropologists have taught us to try to understand all societies in their own terms. Before then, Europeans believed that all peoples could be placed somewhere along a single spectrum from primitive superstition to modern civilization and rational ways of thinking. Such ideas profoundly influenced Christian missionaries, who frequently assumed that part of their job was to move people along the spectrum so that they would become civilized.

A good example is provided by the Puritans who emigrated to North America in the  early 17th century CE. The Puritans made strenuous efforts to bring the gospel to the indigenous inhabitants of the New England colonies. Like other Europeans of the time, their most notable missionary, John Eliot (1604–1690 CE), believed that they needed to be taught the principles of ‘civilization’, which meant persuading them to exchange their nomadic pattern of life for a settled existence under European supervision. Such attempts to reform the traditional lifestyle of the indigenous peoples proved misguided, as they increased their vulnerability to European diseases, to which they had no resistance.

early 17th century CE. The Puritans made strenuous efforts to bring the gospel to the indigenous inhabitants of the New England colonies. Like other Europeans of the time, their most notable missionary, John Eliot (1604–1690 CE), believed that they needed to be taught the principles of ‘civilization’, which meant persuading them to exchange their nomadic pattern of life for a settled existence under European supervision. Such attempts to reform the traditional lifestyle of the indigenous peoples proved misguided, as they increased their vulnerability to European diseases, to which they had no resistance.

The Protestant churches that were formed as a result of the 16th-century Reformation lagged behind the Catholics in their involvement in overseas mission, though the efforts of the New England Puritans were a notable exception. John Wesley (1703–1791), the Anglican clergyman who became the founder of Methodism, is another example from a century later.

The legacy of Christian missionaries is mixed. Christians outside Europe may remember them with affection as their spiritual fathers and mothers. However, in Europe some find their forebears’ unquestioning confidence in their own religious beliefs disturbing. Perhaps the most lasting cultural impact of the missionaries has come through their contributions to Bible translation and education. By translating the Bible into the language of a non-European people, missionaries had to become pupils, learning the finer points of a local language from indigenous teachers.

They had to express Christian doctrines using the terms already available in that language – and that meant allowing Western ideas of Christianity to be modified by the cultural assumptions that shaped the language. What’s more, by giving a people education, missionaries not only taught them Christian beliefs, they also gave them tools that they could put to any purpose they wished.

But the motivation of the missionaries, while perhaps at times well intentioned, was so focused on the urge to convert all people to Christian European practices and belief that there was a devastating effect on the health, cultures and societies of people across the globe.

Christianity in America

Some excellent materials on American Christianity can be found in this article and this interview. Both offer insightful commentary on how Christianity has impacted American policies, life and history, and what is happening with Christianity in American more recently.

Knowing something about the setting of the origins of the faith, the basic beliefs, the traditional practices, and the ongoing developments help all understand the enormous impact of Christianity on our world.

Learning Summary

If you have time, you might enjoy the very fine production from PBS’s Frontline on “From Jesus to Christ”, which is released on line in 2 segments, both almost 2 hours long.

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/documentary/showsreligion/?

McKendrick, Scott. British Library: Discovering Sacred Texts, 2019, www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/the-christian-bible.

“Christianity – Research and Data from the Pew Research Center.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 2021, www.pewresearch.org/topic/religion/religions/christianity/.

“Introduction to Christianity.” The Pluralism Project, Harvard University, 2021, pluralism.org/introduction-christianity.

Lippy, Charles. British Library, Discovering Sacred Texts: Christianity in America, 2019, www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/christianity-in-america.

“Martin Marty – America’s Changing Religious Landscape.” Edited by Krista Tippet, The On Being Project, 21 May 2020, onbeing.org/programs/martin-marty-americas-changing-religious-landscape/.

Meeks, Wayne A. “The Diversity of Early Christianity | From Jesus to Christ – the First Christians | Frontline.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, 1998, www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/first/diversity.html.

“Christianity Comes to Denmark.” National Museum of Denmark, 2021, en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-viking-age/religion-magic-death-and-rituals/christianity-comes-to-denmark/.

crashcourse. “Christianity from Judaism to CONSTANTINE: Crash Course World History #11.” Crash Course World History, 5 Apr. 2012, www.youtube.com/watch?v=TG55ErfdaeY.

- early calendars in the Common or Christian era were based on approximate guesses as to the date of the birth of Jesus of Nazareth, and are judged to be slightly off ↵

- Dr Scot McKendrick is Head of Western Heritage Collections at the British Library. His recent publications include Codex Sinaiticus: New Perspectives on the Ancient Biblical Manuscript (BL Pubs, 2015) and The Art of the Bible: Illuminated Manuscripts from the Medieval World (Thames and Hudson, 2016). ↵

- Brian Stanley is Professor of World Christianity in the School of Divinity in the University of Edinburgh. He has published widely on the history of the missionary movement and its offspring – what is now called ‘world Christianity’. His most recent book is Christianity in the Twentieth Century: A World History (Princeton University Press, 2018). ↵