7.6: Asuka, Nara, and Heian Periods (538 CE – 1185 CE)

- Page ID

- 234225

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

The first significant historical era was based on the Asuka period and was located in the region of previously existing court officials. During this time, Buddhism was introduced to the country, which was different from the Shinto religions existing in the country. There was a substantial amount of contact with people from Korea and China who brought the concepts of Buddhism with them. The immigrants also had new ideas of building, art, and governmental procedures. "With the Chinese written language also came standardized measuring systems, currency in the form of coins, and the practice of recording history and current events. Standardization and record-keeping also encouraged the crystallization of a centralized, bureaucratic government, modeled on the Chinese."[1] The emperor moved the government to Nara and adopted Buddhism as the state religion. With the benefit of imperial supporters, numerous pagoda complexes based on Buddhism were constructed.

The government established a punishing, massive tax structure, unrestrained spending, and extreme religious costs. By the late 8th century, unrest from the people grew, and the new emperor moved the court to Heian-kyo (current Kyoto). By the time of the Heian Period, tranquility was established, and the court could construct a culture based on arts and literature. Just producing artwork or writing words was not an objective; instead, the focus was based on the process: how a word was formed, or the beauty of a single step in a painting.

"The aristocrats who lived in Kyoto considered poetry, music, and all the arts the most important human accomplishments. They included aesthetic skills we rarely think of now, such as mixing incense to make the most beautiful fragrances. Lovers courted each other with poetry, … and affairs succeeded or failed according to the sensitivity of the poems and the beauty of the writer's handwriting (calligraphy). Men often gained favor at court more for their abilities in the arts than for their bureaucratic skills. The tales, romances, and diaries of women became the classics of the literature, and the favored poetic form of this age lasted for the next thousand years."[2]

The Impact of China and Buddhism on Japanese art during the Asuka and Nara Period.

Pagodas

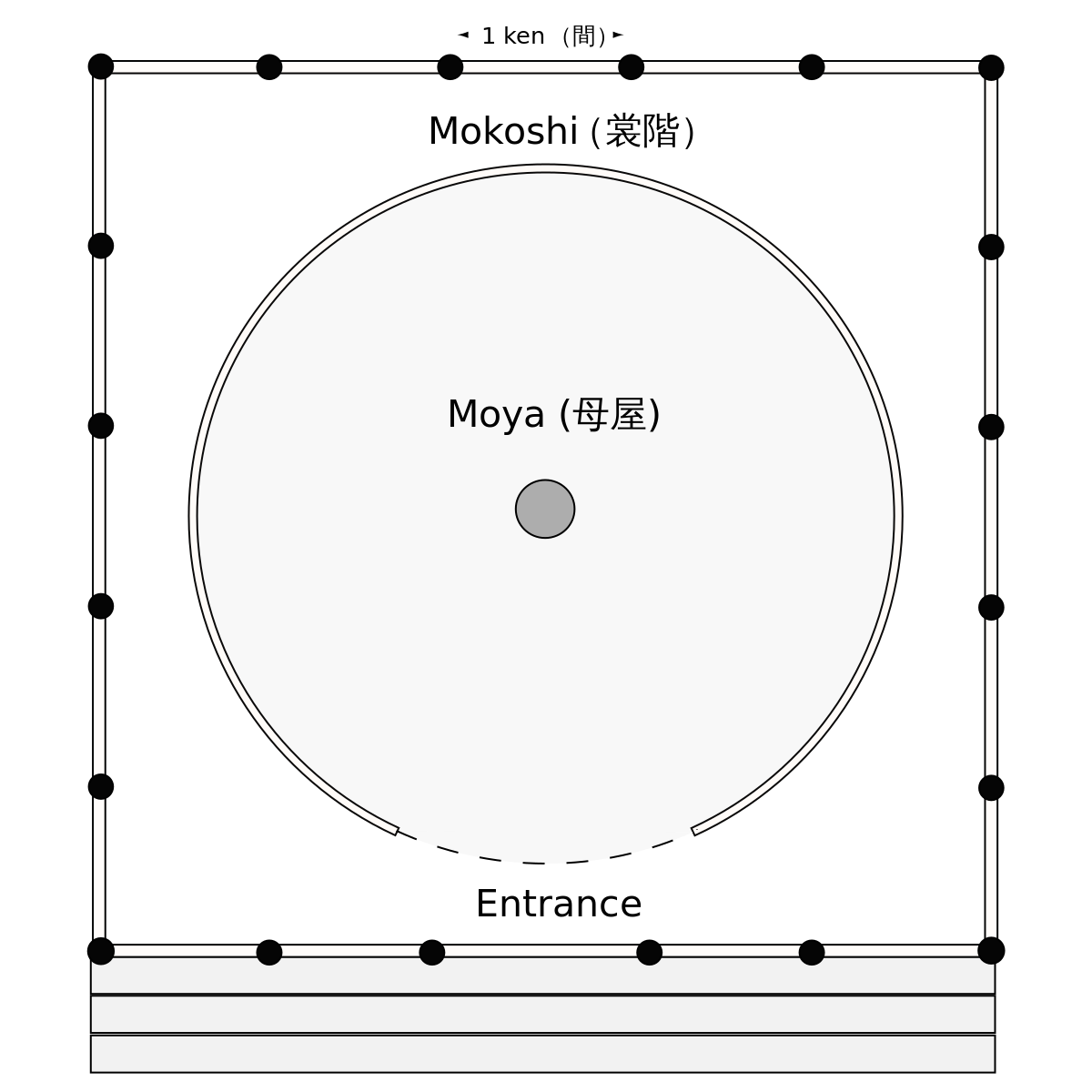

The pagoda's ideas, uses, and structures were based on the Indian stupa or the Chinese pagoda. Stone was not a standard construction material in Japan; only small pagodas were constructed with stone. Pagodas were made from wood, usually two-, three-, or five-stories high. Pagodas were based on the measurement of ken,or the space between two columns. A pagoda was usually square, and in the diagram (7.6.1), one ken is demonstrated by the measured space between pillars. Pagodas were built on a stone base with a central pillar connected to the highest point on the roof. Pillars in a straight line were also installed for the eaves; each story of the pagoda became smaller, with a finial placed on the central pillar. The roofs were hongawarabuki style or flat tiles on most roofs, with curved tiles covering the joints. Decorative tiles were placed along the ridges, gables, or unique corners. Just as the Indian stupas, the pagodas usually had some type of relic as a focal point and were constructed as the tallest building in the complex (7.6.2) and bounded by other halls and structures. Inside the pagoda were statues and paintings representing different deities.

Hokki-ji Temple

In the reign of Prince Shotoku, the Hokki-ji Temple (7.6.3), dedicated to Avalokitesvara, was one of seven temples the prince had constructed. Some historians believed the temple was made over an old palace or building based on pillars buried deep in the ground for support. The Hikki-ji pagoda, constructed in the 8thcentury, is three stories high and still exists today, while the other buildings around the temple are reconstructed. The pagoda and the main hall are laid out on an east-west axis, a layout known as the Hokki-ji style. Inside the pagoda is the 3.5-meter-high wooden statue of the goddess Avalokitesvara, an eleven-faced statue. The bodhisattva was usually represented as a male in India and a female in China and Japan.

Horyu-ji Temple

One of the first seven pagodas constructed in Japan, Horyu-ji Temple (7.6.4) is 32 meters tall, the second highest in Japan. Initially built in 607, a fire destroyed the temple in 670 and again in 711. Surviving earthquakes and the ravages of time, the building was made from interlocking pieces. The central pillar of the pagoda ran three meters into the ground and was tested with "a combination of X-ray photography and dendrochronology (the dating of wood by examining the sequence of annual growth-ring widths) had established that the wood came from a tree felled in 594." [3] Because the tree was cut in 594, it probably was not left until 711 to rebuild the temple. Instead, some historians believe the existing temple was constructed in 607. In 1895, work started to conserve the site as a significant cultural site. However, World War II stopped the work, and large parts of the temple were dismantled to be safely stored. However, the policy of the United States government was to avoid bombing areas of cultural sites, and the region was spared any destruction from the war.

The temple has two major sections, and the Yumedono (7.6.5) is on the eastern side. The Yumedono (hall of dreams) was constructed in 739, and people believed Prince Shotoku meditated here. The building is octagonal shaped with a roof following the hongawarabuki style. The roof followed the divisions of the building and had eight sections. The pagoda stood in the middle of the site and was 32.4 meters high. Located in the pagoda's base are relics considered fragments of Buddha's bones. The pagoda had five stories; however, the inner part of the pagoda did not have any access.

The Kondō (7.6.6) was a vast two-storied hall and measured eighteen meters by fifteen meters. The construction was based on post and beam methods. The roof of the Kondō extended out and needed extra posts to support the roof's weight and curving corners. Inside the Kondō, murals covered the walls. Unfortunately, a fire in 1949 destroyed most of the murals, and only twenty murals (7.6.7) could be saved. From the murals, historians noted clothing on some people generally worn in other countries, indicating the influence of artists from different places. Today, the murals are recreated, and historical images are preserved.

Konpon Daito Pagoda

Mount Kōya is the location of an immense temple complex located in an area surrounded by eight mountain peaks. The location was thought to resemble a lotus plant. Today, the site has a university for religious education and over one hundred sub-temples. The Konpon Daitō Pagoda (7.6.8), also known as the Basic Great Pagoda, is in the center of the temple complex. The large Kondō Hall is located next to the pagoda and is a ceremonial building. The spectacular red and white lacquered pagoda is 48.5 meters high and 25 meters across. The pagoda is constructed in the tahoto style (even number of stories) and has two tiers. The first level was a square, and the second story was more cylindrical. The pyramid-shaped roof had a spire with bells attached to the shaft, chiming as they moved in the breeze.

The inner part of the pagoda is decorated with sixteen columns covered with paintings forming a three-dimensional mandala and the sacred map of Buddhist prayers. Generally, mandalas were only two-dimensional, and the three-dimensional style was considered rare. Four different statues of the five Wisdom Buddhas were located on the four cardinal points, and a separate statue of Dainchi Nyorai (7.6.9), the supreme member of the Wisdom Buddhas.

Murō-ji Temple

The Murō-ji Temple is also located on the hillsides of Mt. Murō, nestled into a cypress tree grove. The Gojyu pagoda (7.6.10) was built during the 9th century and is related to the worship of a dragon spirit. Many caves were found in the surrounding mountains and were believed to be created by dragons. The temple was open to women; most temples were for men only. The pagoda is an impressive five stories high, although each level is exceptionally small in diameter with oversized roofs. The pagoda was also constructed with locally found cypress bark roofing instead of the usual ceramic tiles. Unfortunately, the pagoda was severely damaged in a 1998 typhoon when a tree blown by severe winds fell on the building. The pagoda was restored. Located in another building and created in the Heian period is the wooden seated statue of Sakyamuni (7.6.11). His robes are carved with deep folds, and his legs and feet are arranged in the typical pose. The right hand was raised, and the left was extended, symbolizing courage and offering protection. The right leg sits on the left leg and is considered the Single Lotus Position.

_-_Murouji%252C_Nara.jpg?revision=1)

Mon (gate) is a traditional element for most temples and shrines. The gates are usually symbolic and cannot be closed and locked. The gates note the passageway from the ordinary to the sacred, a cleansing area. Gates are measured in ken, or the width between pillars, and named after how the gate is used. This gate (7.6.12) is a Niōmon style with a roofline like a pagoda. The gate has outer bays holding gods or the Niō. One warrior, Karaen Kongo (7.6.13), has his mouth open and appears to be saying the first letter of the Sanskrit alphabet. The other warrior, Misshaku Kongo (7.6.14), has a closed mouth like an expression used to speak the last letter of the Sanskrit alphabet. The warriors were guardian figures and used to portray power and strength. They generally had oversized muscles, aggressive poses, and bulging muscles, all presenting their warrior skills.

"Each Nio figure represents a particular cosmic sound. Misshaku Kongo's open mouth sounds out "ah," meaning birth. Naeren Kongo sounds "om," meaning death. Thus, in two cosmic sounds, life is encapsulated at the temple doorway, reminding viewers that life is fleeting and that good karma is necessary to avoid rebirth on the Wheel of Life."[4]

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\): Karaen Kongo (663highland, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\): Karaen Kongo (663highland, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Sculptures

As Buddhism was introduced into Japan in the Asuka period, a revival of sculptural art started. Different ideas of shape, form, line, and subject matter also came to Japan and were adopted by local artists. In the Nara period, the government advanced to levels of art and created workshops to produce sculptures, especially those supporting Buddhism. Multiple materials were used, including bronze, copper, clay, and wood, which became the preferred medium. By the Heian period, artists used single pieces of wood to carve a sculpture. Independent artists or temple-sponsored programs replaced the government-sponsored workshops. A specific Japanese style emerged with a gentler appearance and elongated proportions.

Daibutsu is a term used for overly large Buddha statues. This sculpture of the Buddha (7.6.15) is thought to be the oldest intact sculpture in Japan. The sculptor of the bronze statue marked both his name and the date of 609 on the statue. The statue has been restored over time; however, the face is original. The sculpture would be five meters high if the seated image were standing.

Jianzhen, or Ganjin (7.6.16) in Japanese, was from China and helped spread Buddhism throughout Japan. Although an infection blinded him, he made another trip to Japan in 753 and successfully instilled Buddhism in the Japanese court. The imperial court granted him land as a reward, and he founded a religious school. After he died, a dry lacquer sculpture was made of his image. The dry lacquer process was made with a rough clay form. Strips of hemp cloth were soaked in lacquer and then added to the clay form. A mixture of lacquer, sawdust, and powdered clay was added to the sculpture. Each layer had to dry before another layer was added. After the layers hardened, the clay support form was removed. The fabric on the statue was tested, and many historians believe Jianzhen's clothing was used for some of the strips of material used on the sculpture.

Empress Jingu is a person primarily based on legends. Initially, she ruled in Japan in 201. However, information was found in myths, not actual documentation. Images of her have never been found. The stature of Empress Jingu (7.6.17) is carved from a single piece of wood and painted. Her clothing was based on the traditional dress of the Heian period, not actual knowledge. She sat in a familiar pose and had the hairstyle of someone in the imperial court.

Brahma Banton and Indra Tasha Cotton are rare examples of hollow dry lacquer sculptures from Japan. These statues were made in the 8th century when many Buddhist sculptures were produced using this method in Japan. However, from the 9th century onward, carved wooden sculpture became more common, and the hollow dry lacquer technique was abandoned. This makes such sculptures rare today and highly valued by conservators.

Additional text/introduction.

Painting

With the move to Buddhism as the major religion, paintings to honor Buddha became a prominent adornment in temples, halls, and tombs. Because paintings were frequently done on silk, paper, or wood, the survival rate was not very good from these early periods. At the Horyu-ji Temple, a shrine still exists in relatively good condition. The shrine was constructed as a small temple and painted with images of gods, Buddhism, and symbolic designs. The painted doors of the shrine gracefully depict Bodhisattvas (7.6.18) holding a halberd with haloes ringing their heads. "The painting on the Tamamushi shrine is coloured lacquer, a technique which had been used in Korea. The cypress wood of which the shrine is made, however, is said to be of a type found in Japan but not Korea."[5] How the artist painted the images has been controversial. However, recent scientific analysis revealed four oil paint colors (red, light brown, yellow, and green) on lacquered wood. Today, the style is called mitsuda-e because the paint contains lead oxide.[6]

Kichijō-ten (7.6.19) was a minor deity and the goddess of beauty and wealth. She is dressed like a woman of the court and "…the measure of realism, chiefly noticeable in the painting of the ten-e, particularly in the area above the waist, where the colors show through with such charm. The delicacy of this last feature brings to mind some of the creations of the early Flemish masters…"[7] The artist used a heavy layer of paint and added fine black lines for her hair and facial features based on the style of the time. The fabric of her robe was enhanced with gold leaf, and the shiny color with the elaborate folds of the material gave her robe the appearance of movement. The woman is holding a jewel in her hand, symbolizing a goddess.

The Buddhist monks were venerated throughout Buddhist territory, and artists frequently created portraits of different monks. Jion Daishi (7.6.20) was a highly respected monk, and yearly ceremonies in his honor were held in Japan. The monk's clothing is harmonious with contrasting and complimenting colors as he is seated and appears engaged in conversation. The artist outlined the highlights in black ink and used the orange drape on the shoulder right in the center of the painting. The monk appears serious, with his solid, upturned eyebrows enhancing his facial expression. The monk is seated in the Buddhist style, and his religious personality is seen in the painting. During the Heian period, scrolls were popular, and the monk was painted on a silk scroll.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=521&height=844)

.jpg?revision=1)

[1] Asuka period, an introduction

[2] Asia for Educators, Literature of the Heian Period: 794-1185.

[3] Japan Information Network, Trends in Japan, March 29, 2001.

[4] The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, World Myths & Legends in Art

[5] Paine, R. T., Soper, A. C. (1992). The Art and Architecture of Japan, Yale University Press, p. 35.

[6] Terukazu, A. (1977). Treasures of Asia Japanese Painting, (20).

[7] Moran, S. (19620. Artibus Asiae, Kichijoten, A Painting of the Nara Period, 25/4, (238).