5.2: The Maritime and Overland Silk Road (200 BCE - 200 CE)

- Page ID

- 219981

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

The Maritime Silk Road and the Overland Silk Road were prominent trade routes that connected different parts of the world, including Asia, Africa, and Europe. The Maritime Silk Road was established initially around 200 BCE when boats navigated from one port to another along the coastal regions, and it was a vital link for trade in the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. As shipbuilding technology advanced, merchants could travel longer distances across vast oceans to reach other continents. This resulted in the expansion of the Maritime Silk Road, which connected East Asia to Southeast Asia, India, the Middle East, and eventually Europe. The Maritime Silk Road and Overland Silk Road played a significant role in the exchange of goods, ideas, and culture between different regions of the world, and their legacy still resonates today.

"The term 'Silk Road' is a recent invention. The people living along different trade routes did not use it. They referred to the route as the rod to Samarkand (or whatever the next major city was), or sometimes just the 'northern' or 'southern' routes around the Taklamakan Desert. Only in 1877 did Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen coin the phrase 'Silk Road'. He was a prominent geographer who worked in China from 1868 to 1872 surveying coal deposits and ports, and then wrote a five-volume atlas that used the term 'Silk Road' for the first time".[1]

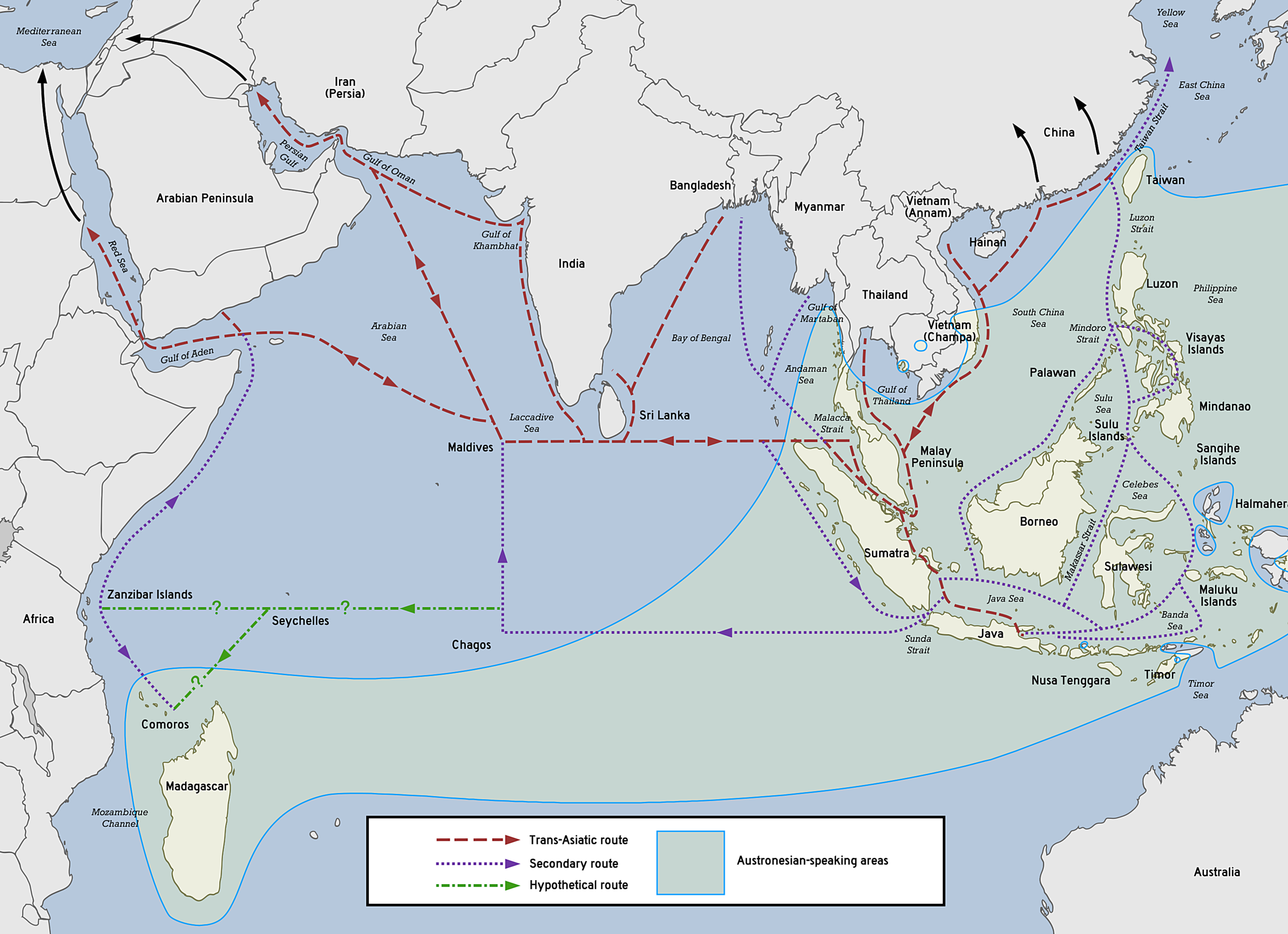

The Maritime Silk Road, also referred to as the Sea Silk Road, was an extensive trade network that linked various civilizations and regions across the Indian Ocean and beyond. It served as a maritime counterpart to the overland Silk Road, enabling the exchange of goods, ideas, and culture, ultimately promoting the growth and enrichment of societies along its routes. The Maritime Silk Road (5.2.1) encompassed multiple branches and routes, connecting regions such as China, Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, East Africa, and Europe. These trade routes were vital for transporting commodities like spices, precious metals, and textiles. Moreover, the sea routes played a significant role in disseminating diverse cultures, religions, and technologies.

The Maritime Silk Road played a critical role in facilitating maritime trade throughout the medieval and early modern eras. Utilizing monsoon winds, sailors were able to navigate the seas with greater efficiency, leading to significant trade activity between the 7th and 15th centuries. Along this route, a number of important ports and trading cities emerged, such as Quanzhou and Guangzhou in China, Malacca in Malaysia, and Calicut and Malabar in India, as well as several ports in the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. These maritime trade routes formed part of a larger interconnected network that connected the East and West, contributing to the globalization of commerce and cultural exchange during this historical period.

The Silk Road served as a vast network of trade routes that connected the East and West, enabling the exchange of goods, ideas, and culture between various regions of Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe. Its origins can be traced back to the Han Dynasty of China, around the 2nd century BCE. While its name was derived from the lucrative silk trade that took place along these routes, the exchange of goods extended far beyond just silk. Along with precious metals, spices, and textiles, many other commodities were also traded. The Silk Road played an essential role in cultural exchange, facilitating the spread of religions, technologies, and philosophies between different civilizations.

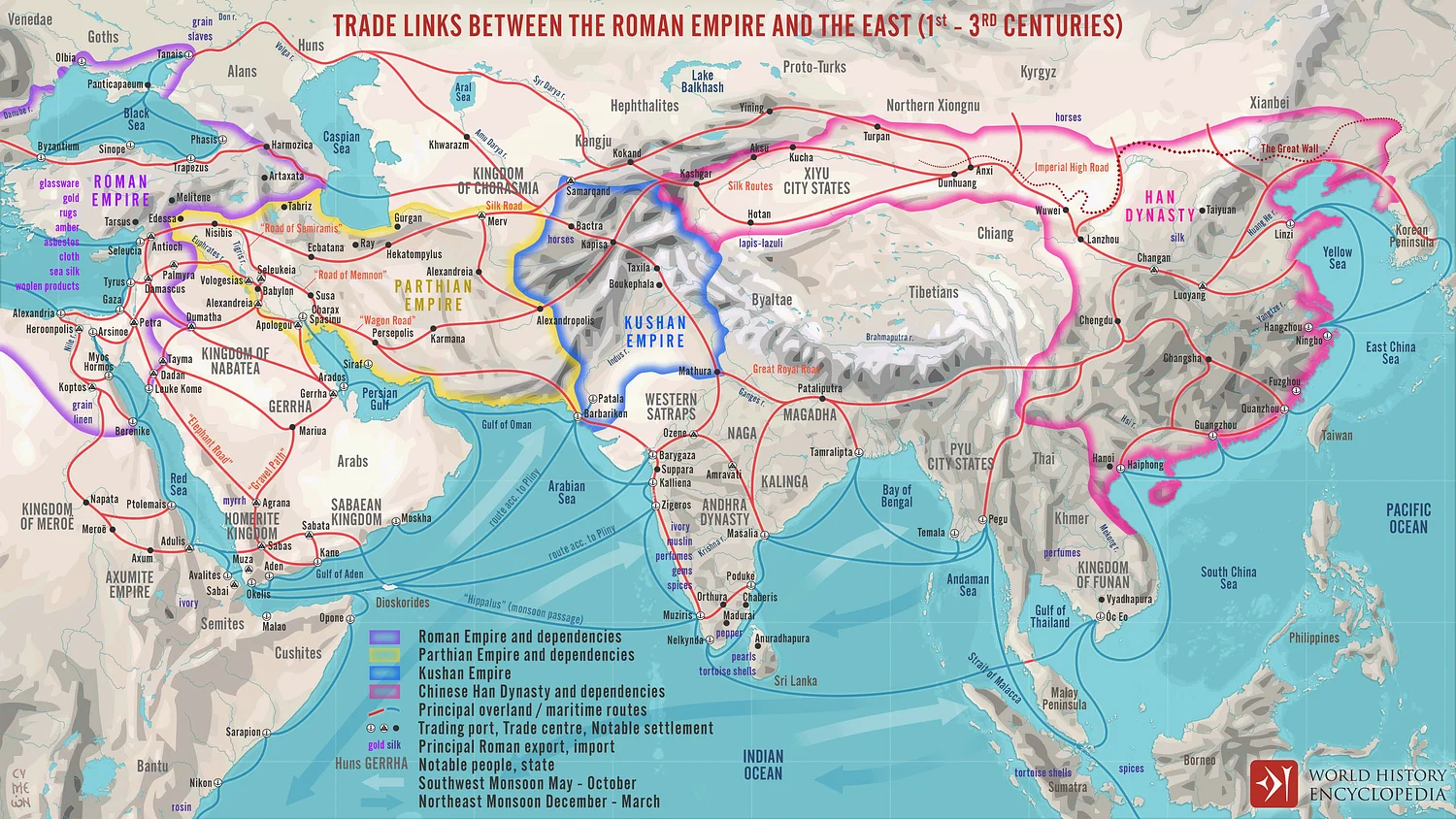

The Silk Road (5.2.2) served as a complex network of interwoven pathways, connecting diverse regions such as China, India, Persia, Central Asia, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean. This vast network consisted of both land and sea routes and was not a singular, clear-cut path. Despite its importance in facilitating economic and cultural exchange, the Silk Road presented a number of obstacles for its traders. Political instability, natural obstructions, and the ever-present danger of banditry were among the many challenges that they had to contend with. Nonetheless, the Silk Road persisted for centuries and left an indelible mark on the development of the civilizations that it traversed.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Silk Road Trade Routes (Simeon Netchev, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Silk Road Trade Routes (Simeon Netchev, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)From ancient times to the medieval era, the Maritime Silk Road (also known as the Indian Ocean trade routes) has served as a trade superhighway connecting India, China, Southeast Asia, the Arab world, East Africa, and the Mediterranean. The Maritime Silk Road is an icon of pre-modern globalization, and we can learn a great deal about the interconnectedness of the ancient and medieval world through examining the unique details of this network. But it was more than just a trade route -- the Maritime Silk Road was traversed not only by merchants, but also diplomats, adventurers, monks, and others.

The Silk Road was the ultimate route for messengers, merchants, and explorers alike. The roads were used in a few manners, with the main being for commercial trade.

Maritime Silk Road

Historians believe that the Maritime Silk Road was responsible for transporting more silk and other goods to the West via sea routes, rather than overland routes.[2] Interestingly, Arab, Persian, and Indian vessels were responsible for the majority of this trade, rather than Chinese ones. The journey was known to be dangerous, with many ships disappearing without a trace. In particular, treacherous areas like the Gelasa Strait, a narrow passageway between the Indonesian islands of Bangka and Belitung, were notorious for their shallow reefs and submerged rocks, making navigation a perilous affair.

During their long voyages, maritime traders had to overcome many obstacles. Fortunately, improvements in sailing technology and ship-building techniques greatly enhanced the safety of sea travel throughout the Middle Ages. Consequently, ports sprang up along the coasts of these maritime trading routes, offering vital chances for merchants not only to trade and disembark but also to obtain fresh water supplies. The scarcity of drinking water was among the most significant dangers faced by sailors. Pirates posed a threat to all merchant ships navigating the maritime Silk Roads, given the high value of their cargos.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: In response to the growing demand for unique spices, medicinal herbs, and raw materials, Chinese merchants worked in collaboration with Indian and Moslem traders to establish an extensive trade network that spanned beyond the Southeast Asian islands to the outskirts of the Indian Ocean. Eastern Chinese ports received shipments of ginseng, lacquerware, celadon, gold and silver, horses, and oxen from Korea and Japan, while southern Chinese ports saw the arrival of hardwoods, ivory, rhinoceros horn, kingfisher feathers, ginger, sulfur, and tin from Vietnam and Siam. From Sumatra, Java, and the Moluccas in island Southeast Asia, imports included cloves, nutmeg, batik fabrics, pearls, tree resins, and bird plumes. Trade winds brought ships carrying cardamom, cinnamon, ginger, turmeric, and especially pepper from Calicut on the southwestern coast of India, gemstones from Ceylon (Sri Lanka), as well as woolens, carpets, and precious stones from ports as distant as Hormuz on the Persian Gulf and Aden on the Red Sea across the Indian Ocean. Although little was known about those areas, China also imported agricultural products from North and East Africa.[3]

The Ming Dynasty was a time when China's naval technology was second to none. Shipbuilders combined their own creative inventions with technology borrowed from seafarers in the South China seas and the Indian Ocean. For centuries, China had been the leading maritime power in the region, thanks to their advancements in navigation, naval architecture, and propulsion.[4] They were even the pioneers of using magnetic compasses aboard ships for navigation, almost two centuries before Europe. Chinese sailors were equipped with printed manuals containing star charts and compass bearings dating back to the thirteenth century, allowing them to navigate using the stars when skies were clear. The production of star charts in China dated back to at least the eleventh century, demonstrating their longstanding fascination with celestial events, which wasn't matched until the Renaissance in Europe.

Overland Silk Road

The Silk Road served as an extensive network of historical trade routes that played a significant role in uniting the East and West. The complex system of trade routes spanned several regions in Asia, Africa, and Europe, connecting East Asia and the Mediterranean world. Its origin can be traced back to the Han Dynasty in China around the 2nd century BCE and facilitated trade in other goods such as precious metals, exotic animals, textiles, and spices. The Silk Road was an extensive network of interconnected land routes that spanned multiple regions. The primary overland routes wound through Central Asia, Persia, and the Middle East, Indian subcontinent, and the Mediterranean coast. In addition to fostering the trade of goods, the Silk Road facilitated the exchange of ideas, religions, and cultures. This exchange enabled the spread of Buddhism from India to East Asia, as well as the transmission of technologies, philosophies, and artistic styles among diverse civilizations.

During its peak period, the Silk Road gave rise to several significant trade centers, including Xi'an in China, Samarkand and Bukhara in Uzbekistan, Baghdad in Iraq, Damascus in Syria, and Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) in Turkey. However, the decline of the Silk Road began in the 15th century as a result of the emergence of maritime trade routes and the declining influence of the Mongol Empire, which had previously facilitated trade across Eurasia. Furthermore, the increasing power of European maritime forces seeking direct access to Asian goods further weakened the significance of overland trade routes.

The Spice Road

The Spice Routes comprised an expansive sea network linking the East and West, stretching over 15,000 kilometers from Japan's western coast, through the Indonesian archipelago, encircling the Indian subcontinent, and reaching as far as the Iranian Plateau, the Arabian Peninsula, and ultimately Europe. These trade routes played a crucial role in enabling the trading of spices on a vast scale and were an integral component of the broader trade networks recognized as the Silk Roads. As far back as 2000 BCE, spices, including cinnamon from Sri Lanka and cassia from China, were traded along the Silk Roads. These valuable commodities were transported to various destinations on the Arabian Peninsula and the Iranian Plateau. The ports where these spice traders stopped served as melting pots for exchanging ideas and information. As goods were traded from one port to another, knowledge was shared across the seas between merchants.

The word "spice" originates from the Latin term "species", which translates to "special merchandise". This refers to goods that hold a distinct value beyond typical trade items. Spices were highly sought after due to their various uses in cooking, religion, medicine, and ceremonies. Their rarity also added to their value, as they could only be grown in specific tropical regions, including southern China, Indonesia, southern India, and Sri Lanka. The Moluccas, a collection of mountainous islands between Sulawesi and New Guinea in the Pacific Ocean, were the primary location for spice growth. Some spices, such as cloves and nutmeg, were exclusive to this area.

The origins of how people discovered and incorporated spices into their diets in regions where they were not originally grown remain somewhat mysterious. What is known, however, is that as trade routes from Indonesia expanded throughout South and Central Asia, they intersected with existing trade routes that spanned Western Asia and other areas, bringing together diverse religious and spiritual customs. The resulting exchange of ideas and beliefs influenced the use of spices in many ways.

Spices were employed for a variety of purposes, including being burned as incense during religious ceremonies to purify the air and convey prayers. They were also added to medicinal ointments and potions believed to counteract specific poisons. Furthermore, spices were routinely burned to cover up unpleasant odors inside homes. In addition, they were utilized early on as culinary ingredients to create novel flavors and to enhance the taste of food, which was sometimes less than fresh, particularly in hot climates. The Silk Roads facilitated the widespread dissemination of spices, herbs, and various culinary practices, forming a communal culinary legacy that continues to be celebrated globally. This cultural exchange also entailed the transmission of nutritional wisdom and beliefs, such as the notion of 'hot and cold' foods in China and the Iranian Plateau, as well as the teachings of Ayurveda from the Indian Subcontinent.

Embark on a culinary voyage with FoodStorian as we unravel the fascinating tale of 'Silk Road Flavors: Culinary Crossroads of East and West'. Join us as we explore the ancient spice trade routes, discover nomadic nosh that fueled Silk Road journeys, witness the Spice Bazaar Showdown, and indulge in the mouthwatering Fusion Feast where flavors from different cultures collide.

Sacred Rocks of Hunza

The Haldeikish, also known as the Sacred Rocks of Hunza (5.2.3), is a significant petroglyph site located along the ancient Silk Route in the Gilgit-Baltistan region of northern Pakistan. These rock carvings, dating back to the 1st millennium CE, hold immense cultural and historical value, providing valuable insights into the artistic and religious practices of ancient civilizations. The intricate carvings on the rocks depict a variety of motifs and symbols, such as human and animal figures, geometric patterns, and inscriptions, offering a glimpse into the rich cultural heritage of the region. The 120 graffiti inscriptions contain names, titles, dates, and formula written in Kharosthi and Brähmi scripts and languages.[6] As one of the earliest petroglyph sites along the Silk Route, the Sacred Rocks of Hunza hold immense academic and historical value. This geological formation has a length of 180 meters and a height of 9 meters. It is comprised of four distinctive boulders and features two stages of rock engravings and carvings. Haldeikish derives its name from the substantial presence of male Ibex that once inhabited the area. The site is adorned with carvings of Ibex, serving as a signal to travelers of the rich and varied fauna that once flourished in the region.

The Sacred Rocks of Hunza are one of the earliest sites of Petroglyphs along the ancient silk route.

Dunhuang City

Situated at the intersection of two major trade routes within the Silk Road network, Dunhuang, a city in north-west China, holds a significant strategic and logistical position. It was one of the first trading cities encountered by merchants entering China from the west, and also served as an important site of Buddhist religious activity. The city acted as a garrison town protecting the region and was a popular destination for pilgrims. The Mogao Caves, an impressive collection of nearly 500 caves in the cliffs to the south of the city, contain the largest depositary of historic documents along the Silk Roads. These caves bear witness to the cultural, religious, social, and commercial activity that took place across the first millennium. Despite changing hands many times over its long history, Dunhuang remained a vibrant hub of exchange until the 11th century, after which its role in Silk Road trade began to decline.

“The Silk Road routes from China to the west passed to the north and south of the Taklamakan Desert, and Dunhuang lay on the junction where these two routes came together. Additionally, the city lies near the western edge of the Gobi Desert…, making Dunhuang a vital resting point for merchants and pilgrims traveling through the region from all directions. As such, Dunhuang played a key role in the passage of Silk Road trade to and from China, …was one of the most important cities to grow up on these routes. Dunhuang initially acted as a garrison town protecting the region and its trade routes, and a commandery was established there in the 2nd century BC by the Chinese Han dynasty. A number of ancient passes, such as the Yü Guan or "Jade Gate" and the Yang Guan, or "Southern Gate", illustrate the strategic importance of the city and its position on what amounted to a medieval highway across the deserts.”[5]

The Dunhuang granary (5.2.4) was a vital structure situated near the Jade Gate that stored grains for transport along trade routes. Constructed using the rammed earth technique, moist soil was compressed into a solid mass to create the building. This structure was pivotal in the trade and commerce of the area, as it stored and distributed grains to various parts of the trade routes. The remains of the Dunhuang watchtower (5.2.5) were among a series of towers that were built every 5 km along the Great Wall of China. These lookout posts, standing around 7 meters tall, were used by soldiers stationed along the wall. In times of emergency, soldiers in the watchtowers would signal information to others stationed along the wall using torches. At the top of each tower, a small room held the necessary supplies for signaling. These watchtowers were a crucial part of the Great Wall of China's defensive network, playing a vital role in safeguarding the region against invaders.

Although the Silk Road has diminished over time, its influence remains prevalent in contemporary society. Linking various regions throughout Asia, it played a crucial part in shaping their economies, cultures, and societies. Even today, it is honored for its promotion of worldwide interconnectedness and cultural exchange. Recently, there has been a growing interest in revitalizing the Silk Road, exemplified by China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The contemporary Silk Road seeks to boost connectivity and collaboration between countries spanning Asia, Africa, and Europe by reestablishing and extending trade and infrastructure networks along the original routes.

[1] Hanson, V. (2012). The Silk Road: A new history. Oxford Press (p. 6).

[2] Sen, T. (2023). Inventing the ‘Maritime Silk Road.’ Modern Asian Studies, 57(4), 1059–1104. doi:10.1017/S0026749X22000348

[3] Asia for Educators - The Ming Voyages. Columbia University.

[4] Needham, J. (1991). Science and Civilization in China. Cambridge, England: University Press. (4) (p. 562).[2]Bauer, S. W., (2007). The History of the Ancient World, W. W. Norton, 657 – 658

[6] Kreutzmann, H. (2006). Karakoram in transition: Culture, development, and ecology in the Hunza Valley. Oxford Press.