2.7: The Costume Team

- Page ID

- 187847

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Introduction: The World of Costumes

Costumes are one of the key design components of contemporary theatre and have played a major role in theatre since its creation. In Ancient Greece, intricate masks transformed actors into literal Gods. In Europe during the Middles Ages, historic records show that Mystery Cycles—plays that featured stories from the Bible—budgeted special funds to costume actors portraying God and his angels, even though lesser characters were often costumed anachronistically. In traditional theatre practices across the globe, from Renaissance England, to Japanese Noh Theatre, to Chinese Xiqu (Chinese opera, in English), the purpose of costumes extended further than establishing details about the character to provide the primary spectacle for the performance, as these theatre practices featured almost no scenery and relied on natural or limited lighting. In fact, costumes were the most valuable asset owned by Renaissance Theatre troupes in many European countries.

But it wasn’t until the last two centuries, when technology advanced enough to allow for less expensive and faster-produced textiles, that Costume Design began to be tailored to specific productions. An increased interest in historical accuracy in the late 18th Century, and a move towards Realism in the late 19th Century, led theatre artists to start thinking about the psychology of characters and how best to communicate specific information about time, place, and origin to the audience. With these developments, the modern Costume Designer was born.

The Purpose of Costumes

While many love costumes for their beauty and creativity, the main purpose of costumes within a theatrical production is to communicate necessary information about the time period and characters to the audience.

Imagine you walk into the grocery store and see a man in a suit and leather dress shoes selecting oranges in the produce section. What would your first assumptions be about him?

You’re unlikely to assume the man in the suit is an employee of the grocery store. Our knowledge of the world tells us that most grocery store employees wear some sort of uniform or utilitarian clothing suited to their required tasks. Depending on the time of day, we might assume that he is on his way home from work. But what does he do for a living? Did he choose the suit or is it a requirement of his employment?

Costumes provide us with a glimpse into a character before they have a chance to speak. They allow us to use our knowledge of the world to make assumptions about where we are and who a person is without having to be told. A skilled Costume Designer can even use an audience’s inferences to surprise them when a character later does something unexpected. Costumes may be used to communicate a character’s personality, wealth or social status, age, sex or gender, confidence level, employment, and more.

Costumes can also work with other design elements to reveal important details about the world of the play, including time period, region or location, weather, time of year, time of day, living conditions, and other important details.

Think of an example of how a person’s clothes might tell you about the time of year or the current weather. How does what you wear change from summer to winter? How much is that affected by the region in which you live?

What are Costumes?

At this point, we should take a moment to talk about what exactly a costume is. If you ask a normal person on the street, they will define a costume as what you dress up in on Halloween or what a child puts on while playing— and they’re not wrong. In the simplest terms, a costume is what a person puts on to pretend to be someone else. And there are actually a lot of different types of costumes in our world with their own names and purposes. Renaissance Faire attendees wear complicated “garb,” a combination of historic garments and modern traditions established by performers and patrons. Reenactors at living history museums and battle reenactments wear historically inspired or replica clothing to enhance patron experiences and learn more about how people lived in a given time period. Cosplayers recreate clothing worn by their favorite fictional characters to wear to gatherings with like-minded fans.

For an actor, a costume is the clothing they put on to become someone else. Many actors rely on costumes as the final step in transforming into their characters on stage. A good costume design will make them feel authentic and believable. But for the character in a play, a costume is not a costume. It’s their clothing. This is how a costume designer must think. The costume designer, like the actor, must think of a character as a real, living, and breathing person and clothe them as if their story were truly happening. Characters should be thought of as people with lives, relationships, families, and histories that have come before and will continue after their appearance in this play.

Pick a character from a favorite book or show. Take a moment to imagine the circumstances your character lives in. Do they have a bedroom? A closet? A trunk? Does someone do their laundry for them? Can they afford a lot of clothing? Did they buy this clothing, or did someone purchase it for them? Is what they wear their choice, or is someone deciding for them? If they woke up on this particular morning—where our play begins—and walked over to that closet, what would they choose to wear?

Costumes from one play to another will be vastly different because the needs of each play are vastly different. The costume designer must approach each play with the question: How do I best support the story being told? If a costume designer does this, then regardless of the play content, their design will usually be effective and genuine.

The People

Costume Designer

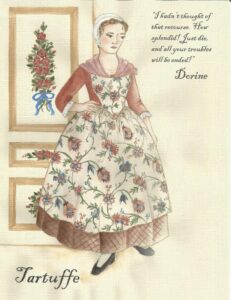

The Costume Designer is a member of the artistic team responsible for the visual appearance of the actor. Depending on the size of the theatre and the production budget, the Costume Designer may be responsible for wig/hair, makeup, and costume properties as well as the actual clothing worn. They may also work closely with Wig and Makeup Designers to ensure each character has a unified look. Costume Designers work with the director and other designers to create a production concept, then create costume renderings, research boards, or collages for each character. The designs are shared with the actors and design team, but serve the primary purpose of showing costume technicians how each finished costume should look.

Costume Technicians

While the Costume Designer creates the look for each character, and often shops for specific costume items, choose fabrics, and makes final decisions during the fitting process, it is the costume technicians working in the costume shop that actually implement the designs for the show. The number of employees, and their assigned tasks, vary significantly based on the size of the theatre. Costume items may be purchased, pulled from “stock” storage from previous productions and altered, rented from another theatre, or built from scratch.

The costume shop is overseen by a Costume Shop Manager or Supervisor, who handles scheduling, budgets, supply inventory, and assignment of tasks. A Cutter/Draper creates patterns using actor measurements and the costume rendering for each built costume. A First Hand is responsible for cutting out the new pattern. The garment is then handed to a Stitcher, who sews it together.

Costumes are fitted in an unfinished state before linings, hems, or closures are added. A Costume Craftsperson, or Dyer, is often employed to handle non-sewing projects, dyeing of fabrics, and distressing to make new-built or purchased costumes appear older, more worn or damaged.

Large costume shops, such as those that build for Broadway shows or film, may also employ armorers, milliners (hat-makers), embroiderers, beaders, jewelry makers, and other more specialized craftspeople. Costume Designers rely heavily on the skills of the technicians that bring their work to life.

The Process

Script Analysis

The first thing any theatrical designer should do is to read and/or listen to the play. Designers glean the text for themes or ideas present in the script, along with important character and setting information, that includes tangible or explicit details like ages, relationships to other characters, socioeconomic status, etc., as well as harder-to-grasp content like personality, perspective, and feelings. The costume designer must know the characters as people, so they can help the audience to know them as well.

Collaboration and Conversation

Most characters can be portrayed in multiple ways because, like real humans, they are complex and multifaceted. After reading the play, the Costume Designer needs to meet with the director and other members of the design team to discuss how the play will be approached. The design team will discuss possible time periods to set the play in, important themes to be highlighted, and how realistically the production will portray the world. Once a concept for the play is established, the designers seek out visual research to support their ideas. Research can be anything from actual clothing items, to photographs or paintings of people, to more abstract evocative artwork, depending on the needs of the production.

Contemporary Realism

Plays are never fully and truly real. They are always a copy of life performed for an audience that can never quite forget they are watching a copy of life. But many plays popular today attempt to come as close as possible to replicating life as we know it now or within our recent memory. For a Costume Designer, designing a realistic, contemporary play is a unique challenge. Everyone in your audience will know if a choice is “wrong” since everyone is subconsciously familiar with the popular trends of today. But at the same time, “right” choices are often completely ignored, in the same way that we pay little attention to the clothing worn by our friends and neighbors. A good contemporary, realistic design will essentially go unnoticed.

Historic Realism

Also called Period Plays, shows that feature costumes from a previous time period but are still meant to represent real life, are sometimes called Historic Realism. These designs make use of historic research, though designs are rarely 100% realistic. Designers must often make use of existing costumes from previous productions and must also consider modern perceptions and aesthetics, as well as more practical concerns, like the actors’ ability to move safely when fighting, dancing, or interacting with other actors.

Non-Realism or Fantasy

Few plays are wholly realistic and may contain a mix of various storytelling elements. Musicals, for example, may appear to exist in the world we live in, but how often have you actually had a friend break into song, accompanied by a full orchestra and chorus of dancing couples, all of whom know the harmonies? Heightened Realism is when a play is mostly recognizable as reality but contains certain elements that may seem far-fetched or larger than life. These moments are often highlighted by changes in costumes or lighting or even the addition of props or scenic elements that don’t otherwise fit the realistic world of the play.

Some plays, however, are complete fantasy and step far away from the real world we know. These productions can offer designers a broader range of creative choices and can be more “fun” to design, but also present their own challenges. Without the boundaries of reality, limiting choices and creating a unified world is more difficult.

Implementation

Once designs have been finalized, the Costume Designer presents their renderings to the costume shop. The shop must decide, based on the timeline, budget, personnel, and other resources, which designs will be made or “built” by the shop, which things can be bought, and which items need to be pulled from storage or rented from another theatre. Many considerations go into these decisions. Has the theatre company done another play in a similar time period? What sizes are the items available in stock? Is the play in a time period where items can easily be purchased?

The Costume Designer will go on to make purchases for the show, including fabrics, clothing items, shoes, trims, and accessories.

The Costume Technicians will begin the build process. Costume shops often make their own patterns specific to the actors’ bodies rather than relying on commercially produced patterns that can be purchased at fabric stores. Mockups using cheaper fabrics are created first to ensure the costume fits well and accommodates the actors’ movements. The costume is then built a second time using the actual fabric. The Costume Designer is usually present at final fittings to ensure the finished garment matches their vision for the character.

During Technical Rehearsals prior to opening, costumes are added to the production at a Dress Rehearsal. Dress Rehearsals allow the actors to practice with their costumes, learn their quick changes, and troubleshoot any issues before an audience is present. A Wardrobe Supervisor and a crew of Dressers assist the actors backstage. Dress rehearsals also allow the director and other designers to see the costumes under the lights and against the scenery. Designers take notes during the rehearsals and may make small changes based on what they observe.

Conclusion

Costumes add a unique element of spectacle to every theatre production, but their success is measured not by how pretty they are but by how effectively they help the audience to understand the characters in the play. A full team of creative artists help the Costume Designer to realize their artistic vision on the stage. Costumes must work with scenery and lights to ensure that the entire production design feels unified and supports the story being told.

Unless your costume department never purchases any fabric, clothing, shoes, or accessories, you are part of the negative environmental impact of the theatre industry. We all know that plays require costumes, which require fabrics, dyes, and often newly purchased elements. How can we minimize the harmful impact our theatrical productions have on the planet? Never fear! There are several ways to design with “greener” methods in mind. Let’s start with things you may already be doing in your costume shop.

Upcycle:

Look through your costume stock and design with these pieces in mind. Can you retrim a garment to give it a fresh look? What about recutting the garment to change the lines? Simple things like adding new sleeves can dramatically change the look of a costume piece. This is not a new practice. If we look at costume history, we can see that having a simple bodice and several pairs of ornate sleeves was a common practice among the nobility in the Tudor era and beyond. Our ancestors were much more frugal and in tune with nature than we are.

Purchase Garments and Accessories from Secondhand Stores:

There are so many thrift and consignment shops available. Most garments needed for modern dress shows can be found gently used and locally sourced. “But what if it is a period piece?” Don’t worry! There are ways to save the planet and support your local thrift store as well. For example, if you need a Regency tailcoat for your Mr. Darcy, try building it from a secondhand suit; simply reshape the jacket and use the fabric from the trousers to create the “tails.” Most tailcoats from this time did not match the trousers, so you have no need to find a suit with two pairs of pants.

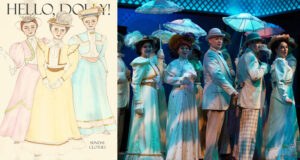

Establish Relationships with Other Theatres:

Professional, community, and college theatres may all be willing to set up a system of reciprocal borrowing. A gown from Hello, Dolly! may work beautifully in your production of A Doll’s House, Part 2. The rules for borrowing include returning the garments cleaned and in the same condition as when they were borrowed. Changing trims and buttons is okay, but permanent alterations or dyeing is not. Some costume shops may allow you to change the trim and leave it on, as long as you ask for permission ahead of time and the original trim is returned along with the garments. In most cases, alterations must be removed, and the garment restored to its original size, shape, and length.

Rent Garments from other Theatres or Professional Costume Rental Houses:

Depending on where you are, there may be rental options close by or ones that require shipping. Remember, the further afield you go, the greater the carbon footprint will be.

Think Outside the Box:

Are there non-traditional materials that you have easy access to which might be used for a costume? In a recent production of She Kills Monsters, I designed costumes using repurposed Amazon gift bags, soda can tabs, plastic bags from wood stove pellets, old foam packaging, and even old pantyhose that became tendrils on a mask.

Most costume shops employ at least one of the methods listed above, but what else can we do to create costumes that not only look good but are created through ecologically sound practices? Here are a few ideas. Not every theatre or designer will be able to employ every method, but by doing as much as we can, we can make a big difference.

Natural Dyes:

Using pre-packaged natural dyes and ecologically friendly mordants is a way to keep potentially harmful chemicals out of your costumes and away from actors’ skin. There are many commercial suppliers, so be certain to look for a company that values sustainable harvesting practices. If you have no local supplier, buying in bulk will lower the carbon footprint. You can also grow or forage your own dyestuff. Many plants will yield lovely shades of yellow, tan, peach, and pink, with a few even offering up orange and purples. Do your research to be certain you are using the proper mordant for your fiber choice. As protein fibers, wool and silk take natural dyes easily and more vividly than cellulose fibers like linen, hemp, or cotton. A few plants to try that may be available in a nearby field are Queen Anne’s lace, fleabane, and goldenrod, which all provide beautiful shades of yellow.

Natural Compostable Fibers:

Using natural fibers onstage is always kinder to your actors, as they are breathable and not composed of chemicals that may irritate the skin. After their working life is over, remove any notions (buttons, zippers, etc.) and tear the old garments into strips and put these in the compost bin. Cotton, hemp, linen, wool, and silk will all break down into soil.

Cotton is a problem plant. Yes, it is a natural cellulose fiber, it is compostable, and few if any people seem to be allergic to cotton textiles. However, there are some issues that make it less than perfect. Cotton needs water. The website, cottoninc.com, tells the reader that cotton mainly uses rainwater and that 64% of U.S. cotton does not use irrigation. If you look at worldwildlife.org/industries/cotton, the story is different. They discuss the heavy use of pesticides, the need for water to be diverted for cotton irrigation, and the negative impact cotton growing can have on certain ecosystems. So, what do you do? Research and learn. Plants like flax (from which linen is made) or hemp, use far less water than cotton and are viable alternatives. Does this mean you should not use cotton? You must make your own decisions but consider looking into organic cotton, which has no pesticide usage.

Textile Recycling:

Textile-to-textile recycling is the idea behind a circular textile economy: creating new materials out of old ones. Vivify Textiles out of Australia, Switzerland, and Italy creates fabrics from recycled nylon and polyester. Companies like FabScrap out of NYC, or Rewoven in Cape Town, South Africa, recycle or sell pre-consumer waste from designers. Textiles that were destined for the landfill may be purchased directly from the companies. Offcuts may be smaller pieces or many yards long. This is a good way to obtain fabric, leather, and notions at reduced prices (in some cases there is yardage or notions you can get for free.) But how good is it for the planet if it has to be shipped? Good question. The process of recycling is imperfect but look for distributors in your area, or at least, not halfway across the planet. Less distance for shipping means a cleaner choice.

No one choice is always the right choice. Every theatre and shop has its own needs, and location and the scale of a production will influence the choices that are made. What we can all do is design with greener choices in mind. Every choice can make a difference in the health of our planet, our communities, and our shops.

Costume

Costume Designer

Costume Technician

Dress Rehearsal

Heightened Realism

Upcycle