2.6: The Set Team

- Page ID

- 187846

A Brief Introduction to and History of Scene Design

From the very beginnings of Western theatre, scenery has played a role in telling the story, defining the story’s location, and creating a world in which the story can live for an audience. The periods in history that shaped our understanding of theatre in the West have had some form of scenery or scenic element as part of the presentation styles. These elements are used to illustrate time, place, social status, and other visual communications.

The Greeks and Romans used the architecture of the theatre itself to create a background while adding elements of mechanical engineering, spectacle, and illusion. These elements took on many forms during this time in history, including wagons, known as the Eccyclema, to reveal tableau scenes and other story moments that were not allowed to be staged live, such as murder and suicide. Additional Greek machines included the Periaktoi, a triangular rotating column to change decorative backgrounds, and the Machina, a crane, used to lower the actors playing a god onto the stage creating the illusion of descending to Earth from above. The Romans took these beginnings to the next level by adding elevators and ramps, full-scale battle reenactments (both land and sea battles), Chariot Races, Gladiator Fights, and multiple levels and entrances to their theatres.

As the Roman Empire ended in the West and Europe transitioned into a different form of governance under the leadership of the Christian Church, theatre came under attack on the grounds of being immoral and evil. Public performance of secular theatre was banned, but theatre found a way to survive. During this period, known as the Medieval or Middle Ages, public theatre was against the law. However, the church used many theatrical elements during their times of special celebration and ritual holy days. Props, costumes, stage blocking, and scripted passages were used during these religious ceremonies. As time moved on, these liturgically staged stories moved to more public venues such as church courtyards and town squares. Eventually, small scenic buildings, called Mansions, were created to accompany a series of staged stories to provide a sense of location. Finally, the stories, props, and mansions were loaded onto wagons and, along with a company of players, traveled from town to town, village to village presenting the staged stories of the church. These traveling groups are known as Pageant Wagon tours and were common from the late Middle Ages into the Renaissance.

As the Renaissance blossomed and population centers grew in both numbers and size, the need for a more permanent and formal theatre space became necessary. It was during this time in history that we witness the beginnings of what is now known as Scene Design. The early theatre spaces attempted to reclaim the ancient glory of classical Greece and Rome. Many of the theatres were designed to replicate the Greek and Roman shape and were designed using large semi-circular seating spaces, marble statuary, and ornately decorated stage spaces with gilded columns and marble decorations. Eventually, these “Neo-Classic” style theatre spaces proved impractical. The evolving styles of storytelling and plays created by the day’s playwrights needed less of the old ways and more new innovations. From this was born what we know today as the Proscenium Theatre. It is also during this period we see new styles of painting and sculpture, focusing on realistic representation of both the human form and architecture. It was the use of perspective, a technique used to create visual depth on a 2-D surface, in painting and drawing that revolutionized theatre design during the Renaissance. It is from here that movable full-stage scenery in the form of “Wing and Drop” is started.

From these humble beginnings, scene design has grown into an art form that allows artists to imagine, create, invent, and discover new ways of communicating location, time, and space. Today, we use technology beyond painting, wagons, and simple rigging to change scenery. In the theatre of the 21st Century, we explore a wide variety of technologies including computer automation, motorized curtains, video and image projection to name a few. A scene designer takes on the role of an artist, engineer, carpenter, painter, plumber, computer programmer, visionary, and research historian— plus a few more. Scenery can be real, imagined, projected, symbolic, representational, and take on many other forms, but it is just one small part of the whole.

The Purpose and Process of Scene Design

What is the purpose of scenery? If one were to ask 10 random audience members that question, I would imagine you would not get very many answers that were the same. Scenery is an assistant to the story and allows a viewer to see what kind of environment a character inhabits... Scenery communicates time and location… Scenery creates a world for the story’s characters to live within… A background…. All of these are valid and useful when thinking about designing a set for a production. That is exactly what designers set out to do. They create a world in which the story can be told, allowing an audience to have a sense of what it was like to live in that world during that time and gain a greater understanding of who the characters are in their lives at this moment.

As mentioned above, scenery can take on many forms today, far more than in days past. That being the case: how does a designer decide which road to travel when creating a design? Much of this decision will lie with the production design team and the director. This group creates ideas that become the creative interpretation for the production. It is the production concept that shapes and informs design choices for the production. If it is decided that the show requires historical realism to accomplish its goal, then the scenery, costumes, props, and other design areas need to create that realism within the finished product. If the group agrees that symbolic elements will best fit the vision, then the designers need to create design ideas to symbolize the needed elements. Whatever the vision or design choice, the scenery will play the role for which it is intended.

The process by which scenery is designed is not too dissimilar to the process the production design team uses when defining the purpose (production concept) for a show. Each design’s creation will take a slightly different journey depending on the needs of the production concept, the available resources, and the deadlines to be met. There are, however, steps that will certainly be needed on each design journey regardless of the production concept.

Once you have begun to work as the designer on a production, one of the first tasks is to read the play. Along with that reading of the play comes the analysis of the script. During this time of script analysis, the designer makes discoveries that inform and shape the choices made for the design. A designer may read the play multiple times to understand the storyline, to understand the space the play requires on stage, and to understand the characters who live in the space the designer will create. During the readings of the play, a designer may make notes about the needs of the physical space, such as a front entryway door, a window that overlooks a backyard, the space is filled with refuse and resembles a college dorm room, or graffiti and posters fill the walls. In addition to making notes about the physical needs, a designer also explores the characters in the story. They may look at a character’s wealth, social status, personality traits, habits, and movement through the space. Finally, a designer may have questions about the script or the requirements of staging a moment in the story. This is the time to ask those questions, as the answers may reveal the need for new thoughts or ideas.

After notes have been made and questions have been answered, it is time to begin the research step. Design research may involve many questions to be solved, and some of those questions may have limited answers, but with a good analysis of the play, solutions will be found. Much of the research a designer does is visual. This type of research requires them to seek out paintings, photographs, architecture, and interior designs that support the production concept. Finding the right color, trim detail, or wallpaper pattern is important, but research goes beyond those surface details and allows for constant learning and discovery. In addition to visual research, a designer also engages in historical research. Historical research can open a world of artistic options for a designer and ensure that choices are historically accurate when those details are required.

Following the research comes the selection of details and ideas. The selection brings all the designer’s research ideas together and the best choices for the production are selected. With these choices made, the designer can move forward to implementation. This is the moment you start putting pencil to paper, cursor to screen, brush to canvas, and saw blades to wood. The drawings are created, models are built, paint elevations are painted, and from these plans and ideas come the scenery constructed for the production. During this realization phase of the process, designers need to be flexible and willing to evolve as the production warrants. Not all challenges can be anticipated, so an ability to accept changes is helpful in successfully completing the project.

Finally, the show is open for viewing by a public audience. Many congratulations are in order and feelings of accomplishment abound, but we must also look deeper into what happened during the process of creation and implementation. Where did the scenery come up short of the mark? How can we adjust for the next production to meet the mark? What were our successes? How do we make sure those continue for future productions? In short, we need to evaluate the process, the communication, the collaboration, and any other elements that affected the scenery and the production as a whole.

The PersonnelInvolved in the Creation of the Scenery for a Production

The Scene Designer is the leader of this area of production and is responsible for the visual appearance and function of the scenery and props. In its simplest form, the scene designer creates the artifacts and visual representations of the scenic elements. These artifacts can be produced in several ways and the final artifacts created are the choice of the designer in collaboration with the director.

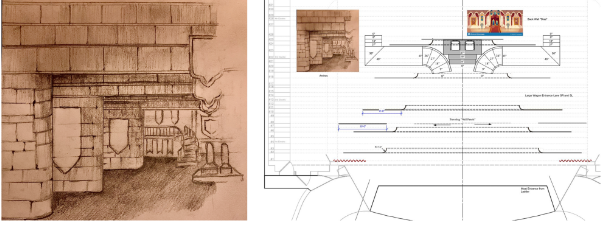

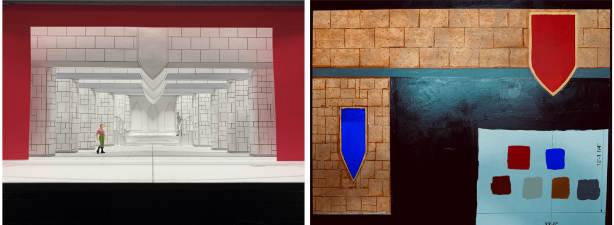

A designer often begins with quick sketches of the design ideas, the individual scenic elements, props, or other elements as needed. Once the design ideas are agreed upon, the designer will move to a more detailed and technical phase of the design during which mechanical scale drawings are created to illustrate the exact size, shape, and minor details of the whole set. These sets of drawings usually include a ground plan, a centerline section, front elevations of all scenic elements, and any other drawings necessary for the completion of the production. In addition to research, sketches, and mechanical drawings, the designer may also create a scale model and paint elevations to illustrate the design choice in 3D scale and in color.

Assisting the Scene Designer with construction is the Technical Director (TD). The TD is responsible for the construction of the scenery and all other technical aspects of the production such as sound, props, and lighting. This does not mean that the TD does all those jobs, but makes sure they move forward safely, on budget, and on schedule. The designer provides the scale drawings of the scenery and, along with the TD, creates a plan for building the needed scenic pieces. There are many factors involved in the building of scenery, including, but not limited to, the show budget, material availability, available labor, and the amount of time allotted for the construction of the scenery.

Assisting the Technical Director with their responsibilities is the Assistant Technical Director (ATD). This position assists the TD with ensuring the safe, on-time, and on-budget completion of the scenery. The ATD also manages the shop equipment inventory, making sure that the tools used in construction are well-maintained and in good working order.

Under the supervision of the Technical Director and Assistant Technical Director, the carpenters build the scenery using wood, metal, fabric, plastics, or the chosen construction material. Once the drawings are in their final form and the construction decisions have been made by the TD and the Scene Designer, the carpenters, props artisans, and welders are assigned their roles in producing the needed scenic elements. Some artists will take a project from beginning to end and others will contribute pieces of the whole. Regardless of the role anyone plays, their contribution is important to that piece of the production.

Once the scenery is constructed it becomes time for painting and finishing details. The person who leads the painting application is known as a Scenic Charge Artist. It is the charge artist who creates and develops, along with the TD and the Scene Designer, the schedule, color palette, and techniques necessary for painting the scenery. The charge artist is responsible for the completion of the painting of the scenery and props. On most productions this may be impossible alone, therefore most scene shops have a paint crew to assist the charge artist with the painting tasks and techniques. Scenic painters need to be familiar with many types of paints, stains, and dyes, along with many application techniques for faux finishes such as foliage, glass, wood grain, and marble.

Parallel to the scenery is the Stage Props. Props are details that become extensions of the larger set, the actors, the story, or the costumes. These details are managed by the Prop Shop and led by the Properties Coordinator. Props add to the understanding and visual communication of the production design concept. Some props are purchased, some are pulled from storage, some are borrowed, and some are designed and built from scratch. It is the director, the scene designer, the TD, and the props coordinator who decide which avenue to travel for each and every prop required for the production.

Finally, the show is built and prepared to open for a live audience. It is now that the Stage Crew, a group of backstage technicians, take on the task of running the show. It is this group that operates the stage fly systems, moves the scenery and props as needed, and keeps the stage clean, clear, and safe for all members of the production company working on the production.

Scene design and all theatre design is an ever-evolving art form that serves an intended purpose within a production. It contributes to contextual understanding of the production’s environment, creates visual interest and intrigue, plus excites audiences with visual spectacles that capture our imaginations in the process. The scene designer is the artist who imagines the possibilities of the world of the play and creates the needed artifacts to make those ideas a reality.

Assistant Technical Director

Carpenters

Production Design Team

Prop Coordinator

Scenic Charge Artist

Scene Designer

Technical Director