6.3: Modest Mussorgsky - Pictures at an Exhibition

- Page ID

- 90718

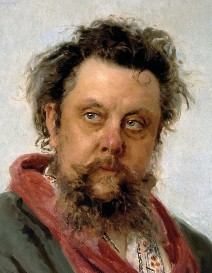

The Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky (1839-1881) was just a generation younger than Berlioz, and their careers overlapped for several decades. The two composers, however, lived in different worlds. Berlioz was French and worked in Paris, a major European cultural center. He received a formal music education and was well-connected with leading figures across the arts. Mussorgsky, on the other hand, was not even a professional composer, and was excluded from his country’s growing musical establishment. His status as an outsider, however, only inspired Mussorgsky to find a unique artistic voice, and he emerged as one of the most important Russian composers of the 19th century.

Mussorgsky and Russian Identity

Mussorgsky’s career was split between military and civil service. He enrolled in Cadet School at the age of 13 and subsequently accepted a commission in the Russian Imperial Guard. He resigned his commission in 1858 so as to be able to focus more energy on music, but it was not feasible for him to compose for a living, so he instead took a series of administrative posts with the government.

Mussorgsky’s main interest, however, was music. He studied composition with Miliy Alexeyevich Balakirev, who had emerged as the ideological leader of the nationalist movement in Russian music. Mussorgsky also developed close personal relationships with the other young composers in Balakirev’s circle, all of whom saw themselves as anti-establishment figures in search of authentic Russian musical expression. Together, these composers were known as “the mighty handful”—an evocative nickname that has been identified with the progressive strain of late 19th-century Russian music ever since.

Despite their interest in developing a uniquely Russian school of composition, Mussorgsky and his colleagues were primarily influenced by European concert music. They studied the scores of Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Chopin, Liszt, and Berlioz, the last of whom they particularly admired. Because they were largely self-trained and valued experimental approaches, however, these composers succeeded in adapting European forms and techniques to their own creative ends.

Capturing Visual Art in Music

Mussorgsky composed Pictures at an Exhibition after attending an art exhibit in commemoration of his friend Viktor Hartmann, who had died suddenly of an aneurism in 1873. Hartmann had belonged to the progressive school of Russian art, which sought to develop a uniquely Russian approach to the visual arts. It is natural enough, therefore, that Mussorgsky should have felt a kinship with Hartmann, for he and “the mighty handful” sought to accomplish the same thing in the realm of music. Mussorgsky had acquired a large number of Hartmann’s paintings, which he allowed to be displayed as part of the exhibit in St. Petersburg.

After walking through the galleries, Mussorgsky was inspired to compose a piece of music that captured the experience in sound. He completed the work in only twenty days. Pictures at an Exhibition was initially conceived of as a ten-movement suite for piano. Each movement represents a Hartmann work, while a “Promenade” interlude between many of the movements symbolizes the act of walking from one painting to the next. Unfortunately, many of the paintings themselves have been lost, but Hartmann’s work has lived on in this enormously popular musical composition.

Mussorgsky wrote for piano in part because he was not a skilled orchestrator. However, a large number of later composers took on that task, and as a result many different versions of Picture at an Exhibition have been performed over the past century. Pictures is heard most frequently as an orchestral work, and the most successful orchestration was created by the French composer Maurice Ravel in 1922. There are also versions for chamber orchestra, band, brass ensemble, and solo guitar. However, the popularity of Pictures has resulted in additional adaptations that live outside the concert hall. It has been performed by numerous rock bands—including Emerson, Lake, and Palmer, who recorded it live in 1971— and even formed the basis for early experiments in the world of electronic music.

For this reason, Pictures at an Exhibition presents a wonderful opportunity to consider the significance of timbre. We will examine two movements in depth, and for each we will compare four different versions: Mussorgsky’s 1874 composition for piano, Ravel’s 1922 orchestration, Japanese synthesizer artist Isao Tomita’s 1975 interpretation, and German thrash metal band Mekong Delta’s 1996 recording. All four versions contain exactly the same pitches and rhythms, but they sound quite different from one another due to the divergent sound qualities available from piano, orchestra, synthesizer, and rock band. It is impossible to argue that one version is the “best.” Instead, each brings unique strengths to the task of sounding Mussorgsky’s composition and each connects with different listeners.

The Gnome

|

Time |

Form |

What to listen for |

|---|---|---|

|

0’00” |

A |

This theme is loud, accented, and angular; it includes many descending and ascending leaps |

|

0’18” B In this theme, the right hand repeats a descending figure that outlines an unusual scale 0’40” A This slow, ominous theme is played quietly in the 0’54” C low range of the piano; it is periodically interrupted by loud fragments of A The left hand descends chromatically while the right 1’47” D hand executes descending leaps; then the parts switch 2’11” B The B theme returns, but the left hand part is reminiscent of the C theme The movement concludes with a rapid passage in 2’37” Coda which the left hand descends and the right hand ascends |

The first movement of Pictures at an Exhibition is entitled “The Gnome.” Although the original Hartmann painting has been lost, it is known to have depicted a grotesque nutcracker with large teeth. It was undoubtedly disturbing. Mussorgsky captured the image in sound using a variety of techniques. “The Gnome” begins with a sequence of abrupt, angular melodic fragments. They are unpredictable and unpleasing, lurching about in a way that mimetically capture the motions of the creature they portray. A second, contrasting section contains an uneven descending melody with a dissonant, oscillating accompaniment. A third section vacillates ominously between low and high pitches, while a final section is loud and threatening. Fragments of the first section interrupt when least expected. Throughout, “The Gnome” is characterized by contrast and surprise, and it concludes with a frightening rush to the final cadence. The listener never knows what is going to happen next and is not given the opportunity to relax.

The piano version contains the unpredictable rhythms and rapid mood changes that are central to Mussorgsky’s vision, but the instrument imposes several limitations. To begin with, striking the keys of a piano always produces essentially the same type of sound. While a piano can execute a large range of pitch and dynamic levels, its ability to do so does not compare to an orchestra, which can play higher, lower, louder, and softer. An orchestra, however, lacks the spontaneity and responsiveness of a solo pianist, who only has to coordinate with herself.

Ravel’s orchestration1 has emerged as the most common because, like Berlioz, he knew how to take full advantage of the ensemble’s potential. He puts the opening melodic gesture in the low strings with an echo in the low brass, thereby

creating a darker and more ominous sound quality than is available from the piano. Punctuations from the percussion section further heighten the tension. The next passage features the warm sounds of flute and celeste, with an accompaniment by the string section using pizzicato (a technique for which players pluck the strings instead of bowing them) and glissando (a technique for which players slide their fingers down the length of the string). Just as Berlioz used the low brass to make his “Dies irae” quotation sound threatening, Ravel uses them to increase the sense of danger and violence in his orchestration. Throughout, he never uses the same combination of instruments twice, thereby introducing an element of variety and surprise that was not available to Mussorgsky.

In his synthesizer version,2 Tomita takes a similar approach, although of course he has a completely different set of sonic tools at his disposal. Like Ravel, Tomita explores a wide variety of sound qualities—some dark and muted, some percussive, some bright and zingy. He also applies modulatory techniques that transform those sounds, including low-frequency oscillation, glissandi, and panning. The end result is yet another gloomy sound world, full of contrast and surprise.

Mekong Delta3 have a more limited sound palette with which to work, but it is well-suited to the task. They differentiate the sections of the piece primarily by changing the role of the drum set. In the first and second sections, the drummer mirrors the rhythms of the melody. In the third and fourth sections, however, the drummer sets up a steady rock beat, which lends the arrangement a sense of growing strength and determination. Other minor variations in instrumentation keep this version interesting throughout.

|

“The Gnome” from Pictures at an Exhibition Composer: Modest Mussorgsky, orchestrated by Maurice 1. Ravel Performance: Wiener Philharmoniker, conducted by Valery Gergiev (2002) |

|

“The Gnome” from Pictures at an Exhibition 2. Composer: Modest Mussorgsky Performance: Isao Tomita (1975) |

|

“The Gnome” from Pictures at an Exhibition 3. Composer: Modest Mussorgsky Performance: Mekong Delta (1996) |

Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks

|

“Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks” from Pictures at an Exhibition. Composer: Modest Mussorgsky Performance: Byron Janis (1962) |

||

|

Time |

Form |

What to listen for |

|

Discordant sounds are produced when the pianist |

||

|

0’00” |

A |

plays two keys that are next to one another; this |

|

humorous effect calls to mind the chirping of chicks |

||

|

0’15” |

A |

|

|

In this section, almost every note has a trill, meaning |

||

|

0’30” |

B |

that the player oscillates quickly between two |

|

adjacent keys |

||

|

Although the right hand plays a new melody, the |

||

|

0’41” |

B’ |

left hand remains stable, indicating that this is a |

|

variation of B; this time, quick passages of notes |

||

|

resemble clucking |

||

|

0’52” |

A |

|

|

1’08” |

Coda |

The very brief coda provides a final cadence |

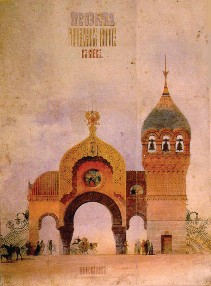

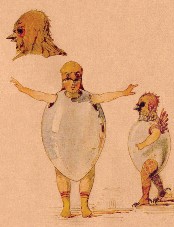

The fifth movement of Pictures at an Exhibition, “Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks,” is quite different. In this case, we still have the artwork that inspired the music. It is not a finished painting, but rather a sketch for a costume that Hartmann had designed for an 1871 production of the ballet Trilby at the Bolshoi Theater. The cast members were to portray unhatched baby chickens dancing in their shells.

Mussorgsky clearly saw the humor in this image, as well as in the dancing that one might imagine to have been performed in such a costume. His brief musical depiction, therefore, is highly comical. He employs a simple ternary form (A B A). Although the A and B sections of the form feature different melodies, we hear the chicks chirping and hopping throughout. While Mussorgsky used dissonance to

signal fear and danger in “The Gnome,” here he uses it to indicate the ridiculous nature of the scene. Occasionally, a lone, sustained note interrupts the dance—the voice of the mother hen, perhaps? An abrupt ending completes the comic effect.

For his orchestrated version,4 Ravel chose to feature the high-pitched instruments whose voices most closely match those of the chicks being portrayed: violin, flute, clarinet, oboe, and bassoon. While he used percussion in “The Gnome” to accentuate the moments of greatest terror, here he uses percussion—cymbals in the A section, snare in the B section—to add comic touches.

Tomita5 takes the idea of comedy the furthest. The same can be said concerning the idea of chickens, for—in an extreme case of mimesis—he uses a variety of simulated clucks and chirps to perform the melody. In the middle section of the form, he pans his chickens between audio channels and fades their voices in and out. Additional comic noises round out the scene.

The members of Mekong Delta6 use rounded timbres in place of distorted ones to create a sound world for “Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks” that is surprisingly far removed from that of “The Gnome.” The regular, energetic rhythmic underpinning from the drummer provides a sense of liveliness. Mekong Delta does not attempt to imitate the sounds of chickens in any way, but instead captures the lighthearted enthusiasm of the Mussorgsky composition.

|

“Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks” from Pictures at an Exhibition 4. Composer: Modest Mussorgsky, orchestrated by Maurice Ravel Performance: Wiener Philharmoniker, conducted by Gustavo Dudamel (2016) |

|

“Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks” from Pictures at an 5. Exhibition Composer: Modest Mussorgsky Performance: Isao Tomita (1975) |

|

“Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks” from Pictures at an 6. Exhibition Composer: Modest Mussorgsky Performance: Mekong Delta (1996) |