6.2: Hector Berlioz - Fantastical Symphony

- Page ID

- 90717

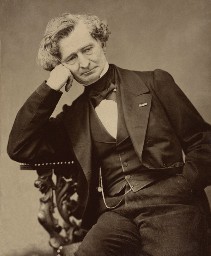

When the French composer Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) premiered what was to be his most famous and influential work, he was only 27 years old. 1830, however, was a big year for the young composer. Not only was his Fantastical Symphony (French: Symphonie Fantastique) premiered in December at the Paris Conservatory, but he also won the Rome Prize (French: Prix de Rome), the top honor for French composers.

However, Berlioz’s training as a composer had been largely self-directed. His father had intended for him to become a physician, and it was to study medicine at the University of Paris that he had first moved to the city. Berlioz completed medical school, despite his disgust at the task of dissecting dead bodies, but he continued to pursue his musical interests throughout the course of his professional education. He gave up medicine upon graduating in 1824 and enrolled in the Paris Conservatory two years later.

During the Romantic era (roughly 1815 to 1900), audiences were fascinated by the personal lives of artists. They tended to understand artistic expression as autobiographical, and they perceived works through the lens of an artist’s personal experience. In the case of Fantastical Symphony this was easy to do, for Berlioz was directly inspired by his own real-world experiences. Before discussing the symphony, therefore, we must dedicate some attention to Berlioz’s love life.

The Origins of Berlioz’s Symphony

In 1827, Berlioz attended a series of Shakespearean performances put on in Paris by a company of Irish actors. Over the course of several plays, he became obsessed with the actress Harriet Smithson, whom he saw in the roles of Ophelia (Hamlet) and Juliet (Romeo and Juliet). His subsequent behavior, which included moving into an apartment from which he could monitor her own dwelling and subjecting her to a deluge of correspondence, can only be described as stalking. She ignored his advances, however, and returned to London in 1829 without ever having met the composer.

Despite never so much as speaking to Harriet, Berlioz felt compelled to channel his passion into musical composition. He let it be widely known that Fantastical Symphony, which tells the story of a romantic obsession gone wrong (details later), was about Harriet Smithson.

Berlioz’s romantic interests were intense but fleeting. He soon recovered from his infatuation with Smithson and in 1830 became engaged to Marie Moke. His status as the winner of the Rome Prize required that he spend several years studying composition in Italy, and while he was abroad he received word from Marie’s mother that she was going to marry the wealthy piano manufacturer Camille Pleyel instead. Berlioz flew into a rage. He purchased guns, poison, and a costume, and boarded a train for Paris with the intention of sneaking into the Moke home dressed as a woman and murdering mother, daughter, and fiance before taking his own life. During the course of the trip, however, his passion cooled, and he abandoned the plan before arriving in Paris. He returned to Italy to complete the terms of his award.

Then, in 1832, Harriet Smithson found herself back in Paris. Berlioz saw that she was provided with a ticket to the premiere of his second symphony, entitled The Return to Life and conceived of as a sequel to Fantastical Symphony. She wrote him a letter complimenting the symphony and the two finally met. They began an affair and married in 1833, although it is widely suspected that Smithson only agreed to the union because of her dire financial situation. The two were not happy, and formally separated in 1843.

In the case of another composer, the above personal details might be gratuitous. In the case of Berlioz, however, they are essential. Not only did his audiences know about his love life, but they relished the opportunity to perceive his music as a window into his most intimate passions. Of course, Fantastical Symphony was not altogether autobiographical. In fact, most of the story, to which we will turn now, was lifted from books that Berlioz was reading at the time.

Berlioz went to great trouble to create, revise, and publicize the story told by his music. He published several versions, the last of which accompanied the 1855 version of the score. It was important to Berlioz that audiences were familiar with the story. For the 1830 premiere, he saw that his narrative was published in Parisian newspapers and distributed to audience members at the performance. (At this time, it was unusual for concert patrons to be provided with a printed program.) In the 1845 version of the score, Berlioz explained the importance of his narrative: “The following programme must therefore be considered as the spoken text of an opera, which serves to introduce musical movements and to motivate their character and expression.” In short, he did not seem to believe that the music could speak entirely for itself.

The Structure and Story of Fantastical Symphony

Berlioz subtitled his Fantastical Symphony “An Episode in the Life of an Artist, in Five Parts.” The artist in question was, of course, himself. The five parts were five distinct movements—an unusual design for a symphony. While most symphonies have four movements, Berlioz was self-consciously following in the footsteps of Ludwig van Beethoven, whose only program symphony—his Symphony No. 6 “Pastoral”—also had five movements. Beethoven’s symphony told the story of a visit to the countryside, but it did so in very vague terms. The only texts were the five movement titles, which described the sensation of peace upon arriving in nature, a scene by a brook, a peasant festival, a thunderstorm, and feelings of relief after the storm had passed. To tell his story, Beethoven deployed musical topics associated with the countryside and incorporated mimetic gestures, including orchestral imitations of droning bagpipes and violent lightning strikes. Berlioz used the same techniques, but took the idea of writing a program symphony much further.

Berlioz’s five movements are entitled “Reveries—Passions,” “A Ball,” “Scene in the Fields,” “March to the Scaffold,” and “Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath.” In the first movement, a young musician catches sight of his ideal woman and immediately falls in love with her. We learn from Berlioz’s text that the musician always hears the same melody in his head when he sees or thinks of her—a melody “in which he recognizes a certain quality of passion, but endowed with the nobility and shyness which he credits to the object of his love.” Berlioz termed this melody the “obsession” (French: idée fixe).

The obsession melody returns in each of the five movements. In the second movement, we hear it when the protagonist glimpses the object of his affection at a ball. In the third movement, the protagonist sits alone in the countryside, listening to shepherds play their pipes. At first he feels hopeful about the future, but he is soon overwhelmed with suspicion and foreboding. The obsession melody reveals the subject of his disturbed brooding.

Because we will examine the fourth and fifth movement in detail, it is worth reading Berlioz’s original description of each in full. His text to accompany the fourth movement reads as follows:

Convinced that his love is spurned, the artist poisons himself with opium. The dose of narcotic, while too weak to cause his death, plunges him into a heavy sleep accompanied by the strangest of visions. He dreams that he has killed his beloved, that he is condemned, led to the scaffold and is witnessing his own execution. The procession advances to the sound of a march that is sometimes sombre and wild, and sometimes brilliant and solemn, in which a dull sound of heavy footsteps follows without transition the loudest outbursts. At the end of the march, the first four bars of the idée fixe reappear like a final thought of love interrupted by the fatal blow.

It is here that we begin to depart notably from reality. Not only did Berlioz never personally have this experience, but it is known with reasonable certainty that he never took drugs of any variety. Instead, he got the idea for this movement from a book he was reading, Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821).

March to the Scaffold

|

Time |

Form |

What to listen for |

|---|---|---|

|

0’00” |

“The procession advances to the sound of a march...” |

A rhythmic pattern played on the timpani sets the scene for a procession |

|

0’28” |

“... that is sometimes sombre and wild, ...” [March theme A] |

This theme, on which we hear many variations, consists of a descending scale with a brief ascending motif at the end |

|

1’40” |

“... and sometimes brilliant and solemn” [March theme B] |

This theme, which is considerably louder and more triumphant, features the brass playing dotted rhythms |

|

March The A theme returns briefly, played by the 2’11” theme A strings and woodwinds in an interlocking texture 2’22” March The B theme returns, this time with an active theme B string accompaniment 2’52” March The A theme returns as it did before theme A The low brass play the descending scale of the 3’00” A theme repeatedly at successively higher pitch levels, thereby building intensity The entire orchestra plays the A theme, first 3’14” in its natural form and then upside down (an ascending scale) 3’40” Coda We hear a new theme at a faster tempo “. . .the first four bars of the idée fixe We hear the obsession melody in the solo 4’17” reappear clarinet like a final thought of love. . .” “. . The melody is cut off by a resounding chord, 4’26” .interrupted symbolizing the fall of the guillotine blade; by the fatal triumphant chords from the brass represent the blow.” cheers of the crowd |

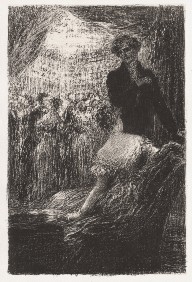

“March to the Scaffold” exhibits all three of the communication techniques outlined above: mimesis, quotation, and the use of musical topics. For most of the movement, we hear two contrasting march themes, one (according to Berlioz’s description) “sombre and wild” and the other “brilliant and solemn.” These themes exemplify the use of musical topics. We are able to recognize them immediately as marches due to the tempo, the brisk character, and the instrumentation, which features percussion and brass. In the final passage of the movement, the tempo accelerates and the excitement builds. Then, out of nowhere, we hear the obsession melody played on a solo clarinet. This, of course, is an example of quotation. We are familiar with this melody and we know that it represents the protagonist’s beloved. We can easily hear it, therefore, as his final thought of her. Before the melody can conclude, a great noise from the orchestra represents the guillotine blade crashing down. This is followed by two pizzicato “bounces” of the severed head and a series of raucous “cheers” from the crowd. All of this is mimesis, for Berlioz uses the orchestra to represent the sounds of the scene he is portraying.

“March to the Scaffold” was the most successful of the symphony’s five movements, and it was frequently programmed as a standalone work during Berlioz’s lifetime. However, the final movement, “Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath,” offers even better examples of our three communication strategies. It is also shows off Berlioz’s extraordinary skill at using the orchestra. The music of Berlioz is still studied today by students of orchestration, and his 1843 Treatise on Instrumentation is still in print. He was also responsible for growing the orchestra in size. Although he wanted 220 musicians for the premiere of Fantastical Symphony, he had to settle for a mere 130. In addition to increasing the size of the string sections, Berlioz increased the number of required wind parts. Fantastical Symphony calls for four different types of clarinets, four bassoons, four harps, and an enormous percussion section, in addition to two instruments—the ophicleide (part of the tuba family) and the cornet à pistons (part of the trumpet family)— that were not typically included in the symphony orchestra. The final movement of Fantastical Symphony makes the most dramatic use of this extensive orchestral palette.

Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath

|

“Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath” from Fantastical Symphony Composer: Hector Berlioz Performance: London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Sir Eugene Goossens (2013) |

||

|

Time |

Form |

What to listen for |

|

0’00” |

“Strange sounds, . . .” |

Tremolo in the violins and violas |

|

0’03” “. . .groans, . . .” Upward sweeps in the cellos and basses 0’17” “. . .outbursts Chromatic descent in the violins and violas of laughter;. . .” 0’32” “. . .distant Call and response between woodwinds and a shouts which muted horn seem to be answered by more shouts.” 0’53” All of the preceding material is repeated, with some variations 1’37” “The beloved We hear the opening of the obsession melody melody appears in the clarinet; it is played at a fast tempo with once more, but an uneven, dance-like rhythm has now lost its noble and shy character; it is now no more than a vulgar dance tune, trivial and grotesque” 1’46” “Roar of The brass enter at top volume delight at her arrival” 1’58” “She joins the We hear the entire obsession melody in the diabolical orgy” high-pitched E-flat clarinet, accompanied primarily by double reeds 3’11 “The funeral The orchestra bells sound the tolling of the knell tolls. . .” knell 3’39” “ . . .burlesque The opening phrase of the “Dies irae” melody parody of the is heard, first in the low brass, then in the Dies irae. . .” trombones at twice the tempo, and finally in the woodwinds and pizzicato strings at twice the tempo again 4’18” The second phrase of the “Dies irae” melody undergoes similar treatment |

|

4’42” The third phrase of the “Dies irae” melody undergoes similar treatment 5’20” “. . . the dance A new theme emerges in the strings of the witches.. .” 5’38” The new theme, which we recognize as “the dance of the witches,” is presented first in the cellos, then the violins, then in the woodwinds 7’28” A hint of the “Dies irae” melody return in the cellos and basses; the other strings play fragments of “the dance of the witches” 8’34” “The dance of We hear complete statements of both the witches melodies layered atop one another, “Dies irae” combined with in the brass and “the dance of the witches” in the Dies irae.” the strings |

Berlioz explained the action in “Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath” as follows:

He sees himself at a witches’ sabbath, in the midst of a hideous gathering of shades, sorcerers and monsters of every kind who have come together for his funeral. Strange sounds, groans, outbursts of laughter; distant shouts which seem to be answered by more shouts. The beloved melody appears once more, but has now lost its noble and shy character; it is now no more than a vulgar dance tune, trivial and grotesque: it is she who is coming to the sabbath… Roar of delight at her arrival… She joins the diabolical orgy… The funeral knell tolls, burlesque parody of the Dies irae, the dance of the witches. The dance of the witches combined with the Dies irae.

The movement opens exactly as Berlioz describes, with “strange sounds, groans, outbursts of laughter.” Strange sounds are certainly heard in the violins. The players employ a technique known as tremolo, in which the bow is moved back and forth very quickly to produce a shaking effect. The cellos undeniably provide the groans, with their quick upward melodic sweeps. Both the violins and trombones can later be heard as laughing. Next we hear “distant shouts” in the high winds, echoed by “more shouts” from a muted horn. The opening passage, therefore, is constructed almost exclusively with the use of mimetic techniques.

When the obsession melody returns, it has indeed transformed in character. It is now a lively, impish dance tune played on the E-flat clarinet—an uncommon, high-pitched version of the instrument with a piercing sound quality. The tune is at first interrupted by a mimetic “roar of delight” from the orchestra, after which it is heard in full. In this case, quotation is combined with the use of a musical topic. We recognize the melody and understand what it represents, but the fact that it is presented as a dance tune adds meaning to its appearance.

After the dance dies away we hear the funeral bells. This barely even counts as mimesis, since Berlioz calls for actual bells to be struck. (He uses the tubular orchestra bells that are included in a standard large percussion section.) Next he employs a second quotation. This time he quotes a melody from outside the symphony—indeed, it is a melody that was composed more than 500 years before Berlioz was even born!

The “Dies irae” comes from the body of medieval Catholic church music known as Gregorian chant. This particular chant was composed in the 13th century and was associated with the funeral Mass, or Requiem. It was sung at the graveside and contains a particularly ominous text. The first three lines read as follows:

A day of wrath; that day, it will dissolve the world into glowing ashes, as attested by David together with the Sibyl.

What trembling will there be, when the Judge shall come to examine everything in strict justice.

The trumpet’s wondrous call sounding abroad in tombs throughout the world shall drive everybody forward to the throne.

The long text continues on to describe the coming of Judgment Day, when sinners are cast into Hell to endure eternal torment. Berlioz’s audience in Catholic France would have recognized this melody immediately, and would likewise have known the associated text. For them, the “Dies irae” carried connotations of terror and hellishness. By using it in his symphony, therefore, Berlioz was able to take advantage of those connotations without incorporating text directly. The “Dies irae” provided the perfect backdrop for his triumphant witches.

Next Berlioz incorporates another dance topic, named in his synopsis as the “dance of the witches.” We don’t recognize the melody itself, but we have no trouble acknowledging that it is a dance, and Berlioz’s description helps us to understand exactly what it going on. Finally, before the raucous conclusion, we hear the “Dies irae” and the “dance of the witches” juxtaposed, each sounding at the same time in a different part of the orchestra. The concluding passage also includes more unusual string techniques, including col legno (with wood), for which players turn their bows over and bounce the stick on their strings. This creates an eerie tapping effect.