6.4: Antonio Vivaldi - The Four Seasons, “Spring”

- Page ID

- 90719

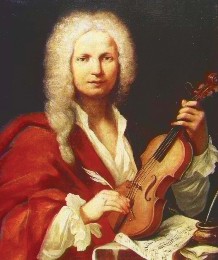

Composers were writing program music long before Berlioz or Mussorgsky. In earlier periods, however, such compositions were generally perceived as entertaining novelties, not the future of concert art. The Italian violinist and composer Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) was particularly fond of program music, and he produced a great deal. His set of violin concertos known as The Four Seasons (Italian: Le quattro stagioni, 1725) are the most famous. Indeed, they rank among the best known pieces of music from the European concert tradition.

Vivaldi’s Career

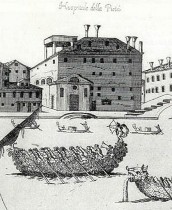

Vivaldi spent his life in the city of Venice, which at the time was a wealthy and independent Republic. He initially trained as a Catholic priest, but ill health prevented him from performing many of his duties. However, he became highly skilled as a violinist and composer, and in 1703 he took the position of violin master at a local orphanage, the Devout Hospital of Mercy (Italian: Ospedale della Pietà; note that Hospital at this time does not indicate a center for medical care). Venetian orphanages were not the squalid workhouses we know from Victorian literature. Indeed, quite the opposite. It was common— even acceptable—for Venetian aristocrats to keep mistresses, but the children of these relationships could not be brought up in the marital home. Instead, unwanted infants were deposited at orphanages via the scaffetta, which was an opening just large enough to fit a newborn. While not all of the surrendered infants were of high birth, the city’s noblemen took an interest in the welfare of their illegitimate children, which meant that the orphanages were always well-funded. The children were brought up with all of the advantages (except parents), and were prepared for comfortable lives.

The Devout Hospital of Mercy, at which Vivaldi took a position, was an orphanage for girls. His job was to teach them the musical skills that would allow them to secure desirable husbands. Vivaldi was exceptionally good at his job, and soon the girls at the orphanage became the best musicians in the city. He not only taught them how to play their instruments but wrote music for them to play. His primary vehicle was the concerto, which is a work for an instrumental soloist accompanied by an orchestra. Over the course of his career, Vivaldi wrote 500 concertos. About half were for violin, including 37 for his most successful protege, a virtuoso known as Anna Maria dal Violin. The other were mostly for bassoon, flute, oboe, and cello—all instruments played by girls at the Hospital.

Naturally enough, the citizens of Venice wanted to hear the girls perform. This, however, presented a serious problem. Women in Venetian society were generally prohibited from performing publicly. Some women took to the opera stage, but in doing so they were confirming their sexual availability and precluding the possibility of marriage. Most of the girls at the orphanage were destined for either husbands or a lifetime of service to the church, so they could not become soiled in this way. Those who did desire a career in music were likely to stay at the orphanage into adulthood, where they were provided with an opportunity to teach and perform. At least two girls who studied at the orphanage, Anna Bon and Vincenta Da Ponte, went on to become composers.

The orphanage developed a clever means by which to facilitate public performances without upsetting social convention. Each Sunday night, a public Vespers service was held for which the orchestra and choir provided music. Although this weekly church service was, for all intents and purposes, a public concert, the simple act of retitling protected the girls’ honor. Members of high society came from across the region to hear the girls, who were physically isolated from the visitors to further ensure their chastity.

Vivaldi was promoted to music director in 1716, and he continued to teach at the orphanage even as he became quite famous outside of Venice. In addition to writing instrumental music, he wrote operas that were staged across Europe and provided choral music for Catholic church services. His long tenure at the orphanage was noteworthy, for male teachers at girls’ orphanages usually got into trouble with one of their charges and eventually had to be dismissed. Vivaldi, on the other hand, developed a reputation for his ethical behavior.

For Vivaldi, the concerto was a relatively new genre. The first concertos had been written by Italian composers in the middle of the 17th century. At first, soloists were used primarily to add variation in volume to an orchestral performance—after all, a few players make less noise than many, and individual string instruments of the time did not have a large dynamic range. Vivaldi still valued the potential for concertos to include a great deal of variety, but he also used them as a vehicle for virtuosic display. The solo parts, therefore, were often quite difficult, and allowed the player to show off her capabilities.

An early 18th-century concerto always followed the same basic form. It would contain three movements in the order fast-slow-fast. The outer movements would both be in ritornello form. “Ritornello” is an Italian term that roughly translates to “the little thing that returns,” and it refers to a passage of music that is heard repeatedly. In a concerto, the ritornello is played by the orchestra. It is heard at the beginning and at the end of a movement, but also frequently throughout, although often not in its entirety. In between statements of the ritornello, the soloist plays. Although the ritornello always remains basically the same, the material played by the soloist can vary widely. The slow movement of a concerto would consist of an expressive melody in the solo instrument backed up by a repetitive accompaniment in the orchestra.

Spring

We will see an example of these forms in Vivaldi’s “Spring” concerto. However, form is certainly not what makes this composition interesting. Vivaldi published his Four Seasons concertos in a 1725 collection entitled The Contest Between Harmony and Invention. This evocative title was supposed to draw attention to novel aspects of Vivaldi’s latest work. While eight of the twelve concertos contained in the collection were adventurous in purely musical terms, the first four were unusual for programmatic reasons.

Each of the Four Seasons concertos— one each for Spring, Summer, Autumn, and Winter—was accompanied by a sonnet. The poetry described the dramatic content of the music, and Vivaldi went to great trouble to indicate exactly how the music reflected the text. To do so, he inserted letter names beside each line of poetry and then placed the same letter at the appropriate place in the score.

The correlation between musical and poetic passages, however, is easy to hear. This, in combination with the fact that no author is indicated, has led most scholars to believe that Vivaldi wrote the sonnets himself.

The sonnet for the “Spring” concerto reads as follows. The lines of poetry are broken up between the three movements, each of which is titled with an Italian tempo marking:

I. Allegro

Springtime is upon us.

The birds celebrate her return with festive song, and murmuring streams are

softly caressed by the breezes. Thunderstorms, those heralds of Spring, roar, casting their dark mantle over heaven,

Then they die away to silence,

and the birds take up their charming songs once more.

II. Largo

On the flower-strewn meadow, with leafy branches rustling overhead, the goat-herd sleeps,

his faithful dog beside him.

III. Allegro

Led by the festive sound of rustic bagpipes, nymphs and shepherds lightly dance beneath the brilliant canopy of spring.

|

Time |

Form |

What to listen for |

|---|---|---|

|

0’00” |

Ritornello - |

The ritornello has an internal form of aabb; |

|

“Springtime is |

its simplicity and repetition suggest a folk |

|

|

upon us.” |

dance |

|

|

0’29” |

A - “The birds |

The solo violinist and two violinists from |

|

celebrate her |

the orchestra join together in imitation of |

|

|

return with festive |

birdsong |

|

|

song, . . .” |

||

|

1’03” |

Ritornello |

The ritornello is slightly abbreviated in this |

|

and all future appearances |

||

|

1’10” |

B - “. . .and |

The entire orchestra plays repetitive figures |

|

murmuring |

that rise and fall, imitating the murmur of |

|

|

streams are softly |

the stream |

|

|

caressed by the |

||

|

breezes.” |

||

|

1’33” |

Ritornello |

|

|

1’40” |

C - |

The orchestra imitates thunder with low- |

|

“Thunderstorms, |

range tremolo and lightning with quick |

|

|

those heralds |

ascending scales; the solo violinist shows |

|

|

of Spring, roar, |

off their virtuosity with rapid arpeggios |

|

|

casting their |

||

|

dark mantle over |

||

|

heaven, . . .” |

||

|

2’08” |

Ritornello |

This ritornello is in the minor mode |

|

2’16” |

D - “Then they die |

The solo violinist slowly ascends using |

|

away to silence, |

repeated notes, suggesting calmness; the |

|

|

and the birds take |

section ends with trills in the the violins, |

|

|

up their charming |

another imitation of birdsong |

|

|

songs once more.” |

|

2’32” Ritornello This ritornello is the least stable, as it moves from one key to another 2’42” E This solo does not correspond with a passage of poetry; its sole function is to prepare the final ritornello 2’56” Ritornello The last thing we hear is the bb section of the ritornello |

The opening ritornello in the first movement captures the spirit of the first line of poetry. It is joyful and exuberant. It is also simple and repetitive, giving the impression that it might really be folk music—the kind of tune one might hear at a country dance. The birds appear with the first solo episode, which requires two violinists from the orchestra to join with the soloist in imitating avian calls. After an orchestral ritornello, we hear some new music from the orchestra that captures the sounds of murmuring streams and caressing breezes. Another ritornello is followed by the thunderstorm. Rapid notes, sudden accents, and violent ascending scales in the orchestra are interrupted by energetic arpeggios in the solo violin, while shifts to the minor mode darken the mood of the passage. After another ritornello, the bird songs gradually reemerge, gaining strength as the storm clears for good. One more solo passage and a final ritornello close out the movement.

The second movement7 is considerably simpler. The solo violin plays a beautiful, calm melody—suitable for the portrayal of a sleeping goat-herd. Underneath, the leafy branches rustle in the violins, who play undulating, uneven rhythms throughout, while the faithful dog barks in the violas. (This last touch is a little strange, for a barking dog would certainly wake the sleeper, but Vivaldi did not have any other tools with which to represent the animal.) The fact that no low strings or harpsichord are present in this movement gives it an ethereal feeling.

|

“Spring,” Movement II Composer: Antonio Vivaldi 7. Performance: Takako Nishizaki with the Shanghai Conservatory Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Cheng-wu Fan (2000) |

The last movement8 has the same form as the first, although the storytelling is considerably less intricate. In the opening ritornello, Vivaldi imitates a bagpipe by having the violas, cellos, and basses sustain long notes outlining the interval of a fifth. The sound is meant to remind the listener of a bagpipe’s drone. The rhythms of the melody are appropriate for dancing, while the lively mood sets the scene for a celebration of spring. The soloist—other than momentarily imitating a bagpipe herself—does not contribute anything in particular to the storytelling. She seems content to interject lively, virtuosic passagework at the appropriate points.

|

“Spring,” Movement III 8. Composer: Antonio Vivaldi Performance: David Nolan with the London Philharmonic Orchestra (2014) |