3.2: Learning Major and Minor Scales

- Page ID

- 52000

Mastering your major and minor scales is a foundational requirement for music theory and music performance. You can greatly assist your mastery of scales by devoting time to them every day. The more types of memory you engage, the better your retention and internalization of the scales. Here is a brief presentation of ways in which you can learn and memorize scales:

Kinetic and Visual Memory

Many musicians learn their scales first on their instruments. For instance, I first learned scales and arpeggios on piano. Later when I studied bassoon I practiced them on that instrument as well. The controlled finger motions I learned with each scale were similar to mastering a dance or gymnastic routine. With more and more practice, I became a “micro athlete” who could progressively reproduce the routine (the scale) with greater accuracy and speed. I made use of kinetic memory–the finger patterns were thoroughly memorized.

Playing scales on piano has the added benefit of encouraging visual memory. Watching fingers move over the landscape of white and black keys also reinforces the scale patterns. Even if you are not a pianist, you will enhance your memory of scales by practicing them at a keyboard. The keyboard is a great tool for visualizing scales.

Cognitive Memory

Cognitive memory and theoretical understanding overlap as categories, but it will be helpful to separate them here for the moment. Remember memorizing your multiplication tables? Rote memorization is also effective for learning your key signatures. Music majors need to rapidly recognize all key signatures and this speed only comes with memorization.

You should be able to immediately do the following:

1) Reproduce the order of sharps and flats. (F#, C#, G#, etc.; Bb, Eb, Ab, etc.)

2) Recognize or reproduce the number of sharps and flats for every key. For instance, you should be able to state quickly that Ab major has four flats, B major has five sharps.

3) Upon seeing a scale written out with accidentals (no key signature), you should immediately know the key.

The tonic (note name) of the relative minor key is a minor third (three half steps) below the tonic of the major key. A minor scale is termed a “relative minor” when it shares a key signature with its relative major. I find it simplest to identify the minor keys by their relationship to the major keys. Of course, I have memorized the more common minor key signatures simply through repeated usage. However, I use the relationship of the minor third for rapid recognition of the minor keys.

Figure 1 supplies the major and minor tonics of the given key signatures. The first example with two sharps has D as the tonic of the major scale and B as tonic of the minor scale. The two notes are separated by three half steps (D to C#, C# to C, C to B). You can also find the major to minor relationship by counting down three scale steps including the first note: D-C#-B. Try verifying the major to minor relationship in the other two examples by counting down by half steps and by scale steps.

Why are key signatures important for memorizing scales? If you know your key signatures, then the scale members will be obvious. For instance, if a major key signature with two sharps is given, the D major scale is required. One does not need to guess whether D major has G# in the scale, for instance. Every scale member is determined by means of the key signature.

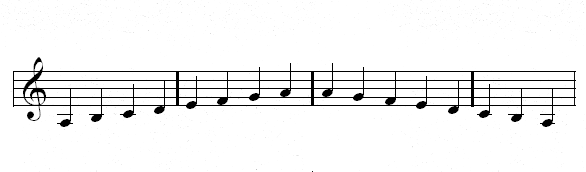

The three common forms of the minor scales can then be remembered in relation to the key signature. You should be able to rapidly reproduce all the minor scales by memorizing the rules given below. The natural minor honors the key signature. It is “natural” since it does not alter the key signature. Below is an example of the A minor scale, a scale which has no sharps or flats in the key signature.

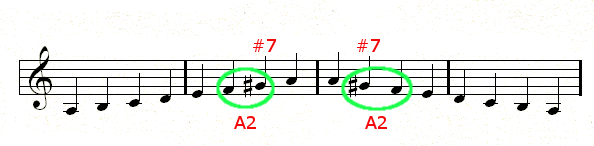

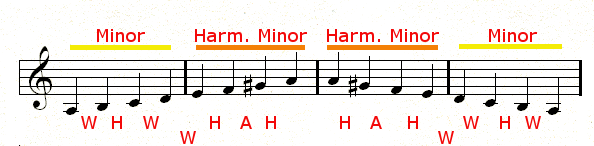

The harmonic minor raises the seventh scale degree both ascending and descending. It is “harmonic” since the raised seventh allows for a dominant chord. A dominant chord in A minor would be E-G#-B.

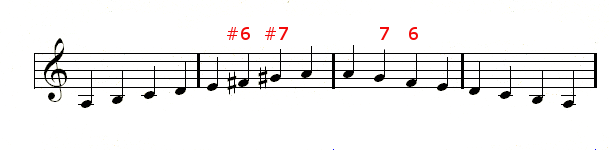

The harmonic minor, with the augmented 2nd (A2) interval, however, presents awkward melodic patterns both ascending and descending. The augmented 2nd interval which contains three half steps is difficult to sing. This leads us to our last common configuration of the minor scale. The melodic minor raises the sixth and seventh scale degrees when ascending but then reverts to the natural minor descending. It is “melodic” since the scale moves in a smooth, step wise fashion ascending to the tonic (here A4) and descending from the tonic.

Theoretical Understanding

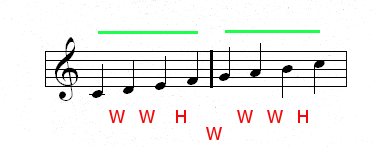

This section presents scale construction by means of tetrachords. One easy method of remembering the order of intervals in the major scale is to divide the scale into two tetrachords, that is, two groupings of four notes. Figure 1 provides a major scale starting on C.

The two tetrachords in the major scale are under the green lines, separated by a bar line. Notice that the interval sequence is the same for the lower and upper tetrachord of the major scale. Each tetrachord has a whole, whole, and half step. Let’s term this sequence of whole and half steps (W, W, H) the “major tetrachord.”

Also notice that the two tetrachords are connected by a whole step (the lowest “W” in the figure). The tetrachords in the major scale as well as those in the minor scales are all connected by a whole step.

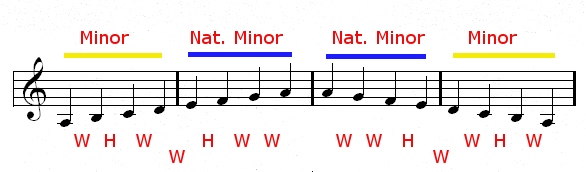

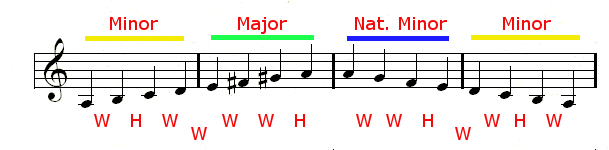

Minor scale construction is more complicated since there are three common forms of the scale. The natural minor features a lower tetrachord common to all the minor scales. We will call this sequence of whole and half steps (W, H, W) the “minor tetrachord.” Study the following figures paying careful attention to the upper tetrachords in each minor scale:

In summary, if you learn the four tetrachords you will be able to construct the major and three minor scales. All the tetrachords are connected by a whole step.

Major scale: lower major tetrachord (W, W, H), upper major tetrachord

Melodic minor scale: lower minor tetrachord (W, H, W), upper natural minor tetrachord (H, W, W)

Harmonic minor scale: lower minor tetrachord, upper harmonic minor tetrachord (H, A, H)

Melodic minor scale ascending: lower minor tetrachord, upper major tetrachord

Melodic minor scale descending: upper natural minor tetrachord, lower minor tetrachord

Conclusion

Familiarizing yourself with all of these ways of knowing major and minor scales will help you to master your scales. You will find that one or two methods work best. Whichever method you choose, however, you must develop rapid recognition of your scales and key signatures. This will take months of practice, so why not start working right now?