5.4: Franz Joseph Haydn

- Page ID

- 72596

While Haydn is not well represented in our current listening playlist, his historical importance cannot be overstated. He was an innovator and a master. His influence on younger composers such as Mozart and Beethoven was substantial. He is known colloquially as “Papa Haydn”.

Biography

Early Life

Joseph Haydn was born in Rohrau, Austria, a village that at that time stood on the border with Hungary. His father was Mathias Haydn, a wheelwright who also served as “Marktrichter,” an office akin to village mayor. Haydn’s mother Maria, née Koller, had previously worked as a cook in the palace of Count Harrach, the presiding aristocrat of Rohrau. Neither parent could read music; however, Mathias was an enthusiastic folk musician, who during the journeyman period of his career had taught himself to play the harp. According to Haydn’s later reminiscences, his childhood family was extremely musical, and frequently sang together and with their neighbors.

Haydn’s parents had noticed that their son was musically gifted and knew that in Rohrau he would have no chance to obtain serious musical training. It was for this reason that they accepted a proposal from their relative Johann Matthias Frankh, the schoolmaster and choirmaster in Hainburg, that Haydn be apprenticed to Frankh in his home to train as a musician. Haydn therefore went off with Frankh to Hainburg 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) away and never again lived with his parents. He was about six years old.

Life in the Frankh household was not easy for Haydn, who later remembered being frequently hungry and humiliated by the filthy state of his clothing. He began his musical training there, and could soon play both harpsichord and violin. The people of Hainburg heard him sing treble parts in the church choir.

There is reason to think that Haydn’s singing impressed those who heard him, because in 1739 he was brought to the attention of Georg von Reutter, the director of music in St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna, who happened to be visiting Hainburg and was looking for new choirboys. Haydn successfully auditioned with Reutter, and after several months of further training moved to Vienna (1740), where he worked for the next nine years as a chorister.

Haydn lived in the Kapellhaus next to the cathedral, along with Reutter, Reutter’s family, and the other four choirboys, which after 1745 included his younger brother Michael. The choirboys were instructed in Latin and other school subjects as well as voice, violin, and keyboard. Reutter was of little help to Haydn in the areas of music theory and composition, giving him only two lessons in his entire time as chorister. However, since St. Stephen’s was one of the leading musical centres in Europe, Haydn learned a great deal simply by serving as a professional musician there.

Like Frankh before him, Reutter did not always bother to make sure Haydn was properly fed. As he later told his biographer Albert Christoph Dies, Haydn was motivated to sing very well, in hopes of gaining more invitations to perform before aristocratic audiences—where the singers were usually served refreshments.

Struggles as a Freelancer

By 1749, Haydn had matured physically to the point that he was no longer able to sing high choral parts. Empress Maria Theresa herself complained to Reutter about his singing, calling it “crowing.” One day, Haydn carried out a prank, snipping off the pigtail of a fellow chorister. This was enough for Reutter: Haydn was first caned, then summarily dismissed and sent into the streets. He had the good fortune to be taken in by a friend, Johann Michael Spangler, who shared his family’s crowded garret room with Haydn for a few months. Haydn immediately began his pursuit of a career as a freelance musician.

Haydn struggled at first, working at many different jobs: as a music teacher, as a street serenader, and eventually, in 1752, as valet–accompanist for the Italian composer Nicola Porpora, from whom he later said he learned “the true fundamentals of composition.” He was also briefly in Count Friedrich Wilhelm von Haugwitz’s employ, playing the organ in the Bohemian Chancellery chapel at the Judenplatz.

While a chorister, Haydn had not received any systematic training in music theory and composition. As a remedy, he worked his way through the counterpoint exercises in the text Gradus ad Parnassum by Johann Joseph Fux and carefully studied the work of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, whom he later acknowledged as an important influence.

As his skills increased, Haydn began to acquire a public reputation, first as the composer of an opera, Der krumme Teufel, “The Limping Devil”, written for the comic actor Johann Joseph Felix Kurz, whose stage name was “Bernardon”. The work was premiered successfully in 1753, but was soon closed down by the censors due to “offensive remarks.” Haydn also noticed, apparently without annoyance, that works he had simply given away were being published and sold in local music shops. Between 1754 and 1756 Haydn also worked freelance for the court in Vienna. He was among several musicians who were paid for services as supplementary musicians at balls given for the imperial children during carnival season, and as supplementary singers in the imperial chapel (the Hofkapelle) in Lent and Holy Week.

With the increase in his reputation, Haydn eventually obtained aristocratic patronage, crucial for the career of a composer in his day. Countess Thun, having seen one of Haydn’s compositions, summoned him and engaged him as her singing and keyboard teacher. In 1756, Baron Carl Josef Fürnberg employed Haydn at his country estate, Weinzierl, where the composer wrote his first string quartets. Fürnberg later recommended Haydn to Count Morzin, who, in 1757, became his first full-time employer.

The Years as Kapellmeister

Haydn’s job title under Count Morzin was Kapellmeister, that is, music director. He led the count’s small orchestra and wrote his first symphonies for this ensemble. In 1760, with the security of a Kapellmeister position, Haydn married. His wife was the former Maria Anna Theresia Keller (1730–1800), the sister of Therese (b. 1733), with whom Haydn had previously been in love. Haydn and his wife had a completely unhappy marriage, from which the laws of the time permitted them no escape. They produced no children. Both took lovers.

Count Morzin soon suffered financial reverses that forced him to dismiss his musical establishment, but Haydn was quickly offered a similar job (1761) by Prince Paul Anton, head of the immensely wealthy Esterházy family. Haydn’s job title was only Vice-Kapellmeister, but he was immediately placed in charge of most of the Esterházy musical establishment, with the old Kapellmeister, Gregor Werner, retaining authority only for church music. When Werner died in 1766, Haydn was elevated to full Kapellmeister.

As a “house officer” in the Esterházy establishment, Haydn wore livery and followed the family as they moved among their various palaces, most importantly the family’s ancestral seat Schloss Esterházy in Eisenstadt and later on Esterháza, a grand new palace built in rural Hungary in the 1760s. Haydn had a huge range of responsibilities, including composition, running the orchestra, playing chamber music for and with his patrons, and eventually the mounting of operatic productions. Despite this backbreaking workload,[n 10] the job was in artistic terms a superb opportunity for Haydn.[n 11] The Esterházy princes (Paul Anton, then from 1762–1790 Nikolaus I) were musical connoisseurs who appreciated his work and gave him daily access to his own small orchestra. During the nearly thirty years that Haydn worked at the Esterházy court, he produced a flood of compositions, and his musical style continued to develop.

Much of Haydn’s activity at the time followed the specific musical interest of his patron Prince Nikolaus. Thus, in about 1765 the Prince obtained, and began to learn to play, the baryton, an uncommon musical instrument similar to the bass viol but with a set of plucked sympathetic strings. Haydn was commanded to provide music for the Prince to play, and over the next ten years produced about 200 works for this instrument in various ensembles, of which the most notable are the 126 baryton trios. But around 1775, for unknown reasons, the Prince abandoned the baryton and took up a new hobby. Opera productions, previously a sporadic event for special occasions, became the focus of musical life in the Prince’s court, and the opera theater he built at Esterháza came to host a major season, with multiple productions, each year. Haydn served as director of the company, recruiting and training the singers and preparing and leading the performances. He also wrote several of the operas performed (see List of operas by Joseph Haydn) and wrote substitution arias to insert into the operas of other composers.

1779 was a watershed year for Haydn, as his contract was renegotiated: whereas previously all his compositions were the property of the Esterházy family, he now was permitted to write for others and sell his work to publishers. Haydn soon shifted his emphasis in composition to reflect this (fewer operas, and more quartets and symphonies) and he negotiated with multiple publishers, both Austrian and foreign. Of Haydn’s new employment contract Jones writes,

This single document acted as a catalyst in the next stage in Haydn’s career, the achievement of international popularity. By 1790 Haydn was in the paradoxical, if not bizarre, position of being Europe’s leading composer, but someone who spent his time as a duty-bound Kapellmeister in a remote palace in the Hungarian countryside.

The new publication campaign resulted in the composition of a great number of new string quartets (the six-quartet sets of Op. 33, 50, 54/55, and 64). Haydn also composed in response to commissions from abroad: the Paris symphonies (1785–1786) and the original orchestral version of The Seven Last Words of Christ (1786), a commission from Cadiz, Spain.

The remoteness of Esterháza, which was farther from Vienna than Eisenstadt, led Haydn gradually to feel more isolated and lonely. He longed to visit Vienna because of his friendships there. Of these, a particularly important one was with Maria Anna von Genzinger (1754–93), the wife of Prince Nikolaus’s personal physician in Vienna, who began a close, platonic, relationship with the composer in 1789. Haydn wrote to Mrs. Genzinger often, expressing his loneliness at Esterháza and his happiness for the few occasions on which he was able to visit her in Vienna; later on, Haydn wrote to her frequently from London. Her premature death in 1793 was a blow to Haydn, and his F minor variations for piano, Hob. XVII:6, may have been written in response to her death.

Another friend in Vienna was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, whom Haydn had met sometime around 1784. According to later testimony by Michael Kelly and others, the two composers occasionally played in string quartets together. Haydn was hugely impressed with Mozart’s work and praised it unstintingly to others. Mozart evidently returned the esteem, as seen in his dedication of a set of six quartets, now called the “Haydn” quartets, to his friend. For further details see Haydn and Mozart.

The London Journeys

In 1790, Prince Nikolaus died and was succeeded as prince by his son Anton. Following a trend of the time, Anton sought to economize by dismissing most of the court musicians. Haydn retained a nominal appointment with Anton, at a reduced salary of 400 florins, as well as a 1000-florin pension from Nikolaus. Since Anton had little need of Haydn’s services, he was willing to let him travel, and the composer accepted a lucrative offer from Johann Peter Salomon, a German violinist and impresario, to visit England and conduct new symphonies with a large orchestra.

The choice was a sensible one because Haydn was already a very popular composer there. Since the death of Johann Christian Bach in 1782, Haydn’s music had dominated the concert scene in London; “hardly a concert did not feature a work by him” (Jones). Haydn’s work was widely distributed by publishers in London, including Forster (who had their own contract with Haydn) and Longman & Broderip (who served as agent in England for Haydn’s Vienna publisher Artaria). Efforts to bring Haydn to London had been undertaken since 1782, though Haydn’s loyalty to Prince Nikolaus had prevented him from accepting.

After fond farewells from Mozart and other friends, Haydn departed Vienna with Salomon on 15 December 1790, arriving in Calais in time to cross the English Channel on New Year’s Day of 1791. It was the first time that the 58-year-old composer had seen the ocean. Arriving in London, Haydn stayed with Salomon in Great Pulteney Street, working in a borrowed studio at the Broadwood piano firm nearby.

It was the start of a very auspicious period for Haydn; both the 1791–1792 journey, along with a repeat visit in 1794–1795, were greatly successful. Audiences flocked to Haydn’s concerts; he augmented his fame and made large profits, thus becoming financially secure. Charles Burney reviewed the first concert thus: “Haydn himself presided at the piano-forte; and the sight of that renowned composer so electrified the audience, as to excite an attention and a pleasure superior to any that had ever been caused by instrumental music in England.” Haydn made many new friends and, for a time, was involved in a romantic relationship with Rebecca Schroeter.

Musically, Haydn’s visits to England generated some of his best-known work, including the Surprise, Military, Drumroll and London symphonies; theRider quartet; and the “Gypsy Rondo” piano trio.

The great success of the overall enterprise does not mean that the journeys were free of trouble. Notably, his very first project, the commissioned operaL’anima del filosofo was duly written during the early stages of the trip, but the opera’s impresario John Gallini was unable to obtain a license to permit opera performances in the theater he directed, the King’s Theatre. Haydn was well paid for the opera (300 pounds) but much time was wasted. Thus only two new symphonies, no. 95 and no. 96 “Miracle“, could be premiered in the 12 concerts of Salomon’s spring concert series.

The end of Salomon’s series in June gave Haydn a rare period of relative leisure. He spent some of the time in the country (Hertingfordbury), but also had time to travel, notably to Oxford, where he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University. The symphony performed for the occasion, no. 92 has since come to be known as the Oxford Symphony, although it been written in 1789.

While traveling to London in 1790, Haydn had met the young Ludwig van Beethoven in his native city of Bonn. On Haydn’s return, Beethoven came to Vienna and during the time up to the second London visit was Haydn’s pupil. For discussion of their relationship, see Beethoven and his contemporaries.

Years of Celebrity in Vienna

Haydn returned to Vienna in 1795. Prince Anton had died, and his successor Nikolaus II proposed that the Esterházy musical establishment be revived with Haydn serving again as Kapellmeister. Haydn took up the position on a part-time basis. He spent his summers with the Esterházys in Eisenstadt, and over the course of several years wrote six masses for them.

By this time Haydn had become a public figure in Vienna. He spent most of his time in his home, a large house in the suburb of Windmühle, and wrote works for public performance. In collaboration with his librettist and mentor Gottfried van Swieten, and with funding from van Swieten’s Gesellschaft der Associierten, he composed his two great oratorios, The Creation (1798) and The Seasons (1801). Both were enthusiastically received. Haydn frequently appeared before the public, often leading performances of The Creation and The Seasons for charity benefits, including Tonkünstler-Societät programs with massed musical forces. He also composed instrumental music: the popular Trumpet Concerto, and the last nine in his long series of string quartets, including the Fifths, Emperor, and Sunrise. A brief work, “Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser” (the “Emperor’s Hymn”; 1797), achieved great success and became “the enduring emblem of Austrian identity right up to the First World War” (Jones); in modern times it became (with different words) the national anthem of Germany.

During the later years of this successful period, Haydn faced incipient old age and fluctuating health, and he had to struggle to complete his final works. His last major work, from 1802, was the sixth mass for the Esterházys, the Harmoniemesse.

Retirement, Illness, and Death

By the end of 1803, Haydn’s condition had declined to the point that he became physically unable to compose. He suffered from weakness, dizziness, inability to concentrate and painfully swollen legs. Since diagnosis was uncertain in Haydn’s time, it is unlikely that the precise illness can ever be identified, though Jones suggests arteriosclerosis.

The illness was especially hard for Haydn because the flow of fresh musical ideas waiting to be worked out as compositions (something he could no longer do) continued unabated. His biographer Dies reported a conversation from 1806:

[Haydn said] “I must have something to do—usually musical ideas are pursuing me, to the point of torture, I cannot escape them, they stand like walls before me. If it’s an allegro that pursues me, my pulse keeps beating faster, I can get no sleep. If it’s an adagio, then I notice my pulse beating slowly. My imagination plays on me as if I were a clavier.” Haydn smiled, the blood rushed to his face, and he said “I am really just a living clavier.”

The winding down of Haydn’s career was gradual. The Esterházy family kept him on as Kapellmeister to the very end (much as they had with his predecessor Werner long before), but they appointed new staff to lead their musical establishment: Johann Michael Fuchs in 1802 as Vice-Kapellmeister and Johann Nepomuk Hummel as Konzertmeister in 1804. Haydn’s last summer in Eisenstadt was in 1803, and his last appearance before the public as a conductor was a charity performance of The Seven Last Words on 26 December 1803. As debility set in, he made largely futile efforts at composition, attempting to revise a rediscovered Missa brevis from his teenage years and complete his final string quartet. The latter project was abandoned for good in 1805, and the quartet was published with just two movements.

Haydn was well cared for by his servants, and he received many visitors and public honors during his last years, but they could not have been very happy years for him. During his illness, Haydn often found solace by sitting at the piano and playing his Emperor’s hymn.

A final triumph occurred on 27 March 1808 when a performance of The Creation was organized in his honor. The very frail composer was brought into the hall on an armchair to the sound of trumpets and drums and was greeted by Beethoven, Salieri (who led the performance) and by other musicians and members of the aristocracy. Haydn was both moved and exhausted by the experience and had to depart at intermission.

Haydn lived on for 14 more months. His final days were hardly serene, as in May 1809 the French army under Napoleon launched an attack on Vienna and on 10 May bombarded his neighborhood. According to Griesinger, “Four case shots fell, rattling the windows and doors of his house. He called out in a loud voice to his alarmed and frightened people, ‘Don’t be afraid, children, where Haydn is, no harm can reach you!’. But the spirit was stronger than the flesh, for he had hardly uttered the brave words when his whole body began to tremble.” More bombardments followed until the city fell to the French on 13 May. Haydn, was, however, deeply moved and appreciative when on 17 May a French cavalry officer named Sulémy came to pay his respects and sang, skillfully, an aria from The Creation.

On 26 May Haydn played his “Emperor’s Hymn” with unusual gusto three times; the same evening he collapsed and was taken to what proved to be to his deathbed. He died peacefully at 12:40 a.m. on 31 May 1809, aged 77.

On 15 June, a memorial service was held in the Schottenkirche at which Mozart’s Requiem was performed. Haydn’s remains were interred in the local Hundsturm cemetery until 1820, when they were moved to Eisenstadt by Prince Nikolaus. His head took a different journey; it was stolen shortly after burial by phrenologists, and the skull was reunited with the other remains only in 1954; for details see Haydn’s head.

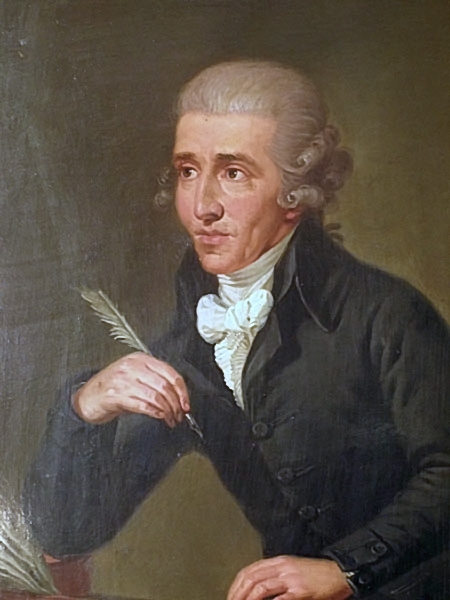

Character and Appearance

James Webster writes of Haydn’s public character thus: “Haydn’s public life exemplified the Enlightenment ideal of the honnête homme (honest man): the man whose good character and worldly success enable and justify each other. His modesty and probity were everywhere acknowledged. These traits were not only prerequisites to his success as Kapellmeister, entrepreneur and public figure, but also aided the favorable reception of his music.” Haydn was especially respected by the Esterházy court musicians whom he supervised, as he maintained a cordial working atmosphere and effectively represented the musicians’ interests with their employer; see Papa Haydn and the tale of the”Farewell” Symphony. Haydn had a robust sense of humor, evident in his love of practical jokes and often apparent in his music, and he had many friends. For much of his life he benefited from a “happy and naturally cheerful temperament,” but in his later life, there is evidence for periods of depression, notably in the correspondence with Mrs. Genzinger and in Dies’s biography, based on visits made in Haydn’s old age.

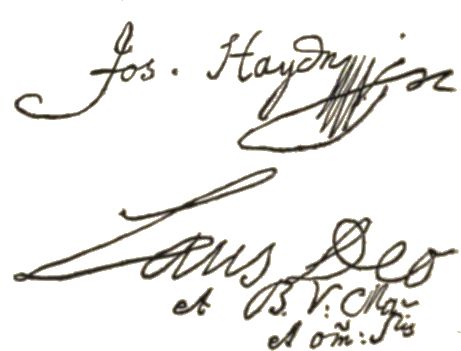

Haydn was a devout Catholic who often turned to his rosary when he had trouble composing, a practice that he usually found to be effective. He normally began the manuscript of each composition with “in nomine Domini” (“in the name of the Lord”) and ended with “Laus Deo” (“praise be to God”).

Haydn’s primary character flaw was greed as it related to his business dealings. Webster writes: “As regards money, Haydn was so self-interested as to shock [both] contemporaries and many later authorities. . . . He always attempted to maximize his income, whether by negotiating the right to sell his music outside the Esterházy court, driving hard bargains with publishers or selling his works three and four times over; he regularly engaged in ‘sharp practice’ and occasionally in outright fraud. When crossed in business relations, he reacted angrily.” Webster notes that Haydn’s ruthlessness in business might be viewed more sympathetically in light of his struggles with poverty during his years as a freelancer—and that outside of the world of business, in dealings, for example, with relatives and servants and in volunteering his services for charitable concerts, Haydn was a generous man.

Haydn was short in stature, perhaps as a result of having been underfed throughout most of his youth. He was not handsome, and like many in his day he was a survivor of smallpox; his face was pitted with the scars of this disease. His biographer Dies wrote: “He couldn’t understand how it happened that in his life he had been loved by many a pretty woman. ‘They couldn’t have been led to it by my beauty.'”

His nose, large and aquiline, was disfigured by the polypus he suffered during much of his adult life, an agonizing and debilitating disease that at times prevented him from writing music.

Contributors and Attributions

- Joseph Haydn. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Haydn. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike