14.4: French Opera

- Page ID

- 72451

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Beginning of a French Tradition

In rivalry with imported Italian opera productions, a separate French tradition was founded by the Italian Jean-Baptiste Lully at the court of King Louis XIV. Despite his foreign origin, Lully established an Academy of Music and monopolized French opera from 1672. Starting with Cadmus et Hermione, Lully and his librettist Quinault created tragédie en musique, a form in which dance music and choral writing were particularly prominent. Lully’s operas also show a concern for expressive recitative which matched the contours of the French language. In the eighteenth century, Lully’s most important successor was Jean-Philippe Rameau, who composed five tragédies en musique as well as numerous works in other genres such as opéra-ballet, all notable for their rich orchestration and harmonic daring. Despite the popularity of Italian opera seria throughout much of Europe during the baroque period, Italian opera never gained much of a foothold in France, where its own national operatic tradition was more popular instead. After Rameau’s death, the German Gluck was persuaded to produce six operas for the Parisian stage in the 1770s. They show the influence of Rameau, but simplified and with greater focus on the drama.

Opéra Comique

At the same time, by the middle of the eighteenth century another genre was gaining popularity in France: opéra comique. Opéra comique is a genre of French opera that contains spoken dialogue and arias—much like the German Singspiel. The form arose in the early eighteenth century in the theaters of the two annual Paris fairs, the Foire Saint Germain and the Foire Saint Laurent. There, plays began to include musical numbers called vaudevilles, which were existing popular tunes refitted with new words. The plays were humorous and often contained satirical attacks on the official theaters such as the Comédie Française. In 1715 the two fair theaters were brought under the aegis of an institution called the Théâtre de l’Opéra-Comique. In spite of fierce opposition from rival theaters the venture flourished and leading playwrights of the time, including Alain René Lesage and Alexis Piron, contributed works in the new form.

The Querelle des Bouffons (1752–54), a quarrel between advocates of French and Italian music, was a major turning-point for opéra comique. Members of the pro-Italian faction, such as the philosopher and musician Jean-Jacques Rousseau, attacked serious French opera, represented by the tragédies en musique ofJean-Philippe Rameau, in favour of what they saw as the simplicity and “naturalness” of Italian comic opera (opera buffa), exemplified by Pergolesi’s La serva padrona, which had recently been performed in Paris by a travelling Italian troupe. In 1752, Rousseau produced a short opera influenced by Pergolesi, Le devin du village, in an attempt to introduce his ideals of musical simplicity and naturalness to France. Its success attracted the attention of the Foire theaters. The next year, the head of the Saint Laurent theatre, Jean Monnet, commissioned the composer Antoine Dauvergne to produce a French opera in the style of La serva padrona. The result was Les troqueurs, which Monnet passed off as the work of an Italian composer living in Vienna who was fluent in French, thus fooling the partisans of Italian music into giving it a warm welcome. Dauvergne’s opera, with a simple plot, everyday characters, and Italianate melodies, had a huge influence on subsequent opéra comique, setting a fashion for composing new music, rather than recycling old tunes. Where it differed from later opéras comiques, however, was that it contained no spoken dialogue. In this, Dauvergne was following the example of Pergolesi’s La serva padrona.

The short, catchy melodies which replaced the vaudevilles were known as ariettes and many opéras comiques in the late eighteenth century were styled comédies mêlées d’ariettes. Their librettists were often playwrights, skilled at keeping up with the latest trends in the theatre. Louis Anseaume, Michel-Jean Sedaine andCharles Simon Favart were among the most famous of these dramatists. Notable composers of opéras comiques in the 1750s and 1760s include Egidio Duni, Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny and François-André Danican Philidor. Duni, an Italian working at the francophile court of Parma, set Anseaume’s libretto Le peintre amoureux amoureux de son modèle in 1757. Its success encouraged the composer to move to Paris permanently and he wrote twenty or so more works for the French stage. Monsigny collaborated with Sedaine in works which mixed comedy with a serious social and political element. Le roi et le fermier (1762) contains Enlightenment themes such as the virtues of the common people and the need for liberty and equality. Their biggest success, Le déserteur (1769), concerns the story of a soldier who has been condemned to death for deserting the army. Philidor’s most famous opéra comique was Tom Jones (1765), based on Henry Fielding’s novel of the same name. It is notable for its realistic characters and its many ensembles.

The most important and popular composer of opéra comique in the late eighteenth century was André Ernest Modeste Grétry. Grétry successfully blended Italian tunefulness with a careful setting of the French language. He was a versatile composer who expanded the range of opéra comique to cover a wide variety of subjects from the Oriental fairy tale Zémire et Azor (1772) to the musical satire of Le jugement de Midas (1778) and the domestic farce of L’amant jaloux (also 1778). His most famous work was the historical “rescue opera”, Richard Coeur-de-lion (1784), which achieved international popularity, reaching London in 1786 and Boston in 1797.

Between 1724 and 1762 the Opéra-Comique theatre was located at the Foire Saint Germain. In 1762 the company was merged with the Comédie-Italienne and moved to the Hôtel de Bourgogne. In 1783 a new, larger home was created for it at the Théâtre Italien (later renamed the Salle Favart).

The French Revolution brought many changes to musical life in Paris. In 1793, the name of the Comédie-Italienne was changed to the Opéra-Comique, but it no longer had a monopoly on performing operas with spoken dialogue and faced serious rivalry from the Théâtre Feydeau, which also produced works in the opéra comique style. Opéra comique generally became more dramatic and less comic and began to show the influence of musical romanticism. The chief composers at the Opéra-Comique during the Revolutionary era were Étienne Méhul, Nicolas Dalayrac, Rodolphe Kreutzer and Henri Montan Berton. Those at the Feydeau included Luigi Cherubini, Pierre Gaveaux, Jean-François Le Sueur and François Devienne. The works of Méhul (for example Stratonice, 1792; Ariodant, 1799), Cherubini (Lodoiska, 1791; Médée, 1797; Les deux journées, 1800) and Le Sueur (La caverne, 1793) in particular show the influence of serious French opera, especially Gluck, and a willingness to take on previously taboo subjects (e.g. incest in Méhul’s Mélidore et Phrosine, 1794; infanticide in Cherubini’s famous Médée). Orchestration and harmony are more complex than in the music of the previous generation; attempts are made to reduce the amount of spoken dialogue; and unity is provided by techniques such as the “reminiscence motif” (recurring musical themes representing a character or idea).

In 1801 the Opéra-Comique and the Feydeau merged for financial reasons. The changing political climate – more stable under the rule of Napoleon – was reflected in musical fashion as comedy began to creep back into opéra-comique. The lighter new offerings of Boieldieu (such as Le calife de Bagdad, 1800) andIsouard (Cendrillon, 1810) were a great success. Parisian audiences of the time also loved Italian opera, visiting the Théâtre Italien to see opera buffa and works in the newly fashionable bel canto style, especially those by Rossini, whose fame was sweeping across Europe. Rossini’s influence began to pervade French opéra comique. Its presence is felt in Boieldieu’s greatest success, La dame blanche (1825) as well as later works by Auber (Fra Diavolo, 1830; Le domino noir, 1837), Hérold (Zampa, 1831), and Adolphe Adam (Le postillon de Longjumeau, 1836).

By the 1820s, Gluckian influence in France had given way to a taste for Italian bel canto, especially after the arrival of Rossini in Paris. Rossini’s Guillaume Tell helped found the new genre of Grand Opera, a form whose most famous exponent was another foreigner, Giacomo Meyerbeer. Meyerbeer’s works, such as Les Huguenots emphasised virtuoso singing and extraordinary stage effects. Lighter opéra comique also enjoyed tremendous success in the hands of Boïeldieu, Auber, Hérold and Adolphe Adam. In this climate, the operas of the French-born composer Hector Berlioz struggled to gain a hearing. Berlioz’s epic masterpiece Les Troyens, the culmination of the Gluckian tradition, was not given a full performance for almost a hundred years.

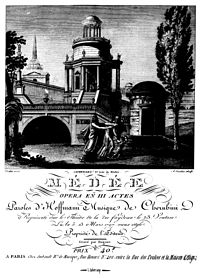

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Jacques Offenbach created operetta with witty and cynical works such as Orphée aux enfers, as well as the opera Les Contes d’Hoffmann; Charles Gounod scored a massive success with Faust; and Bizet composed Carmen, which, once audiences learned to accept its blend of romanticism and realism, became the most popular of all opéra comiques. Jules Massenet, Camille Saint-Saëns and Léo Delibes all composed works which are still part of the standard repertory, examples being Massenet’s Manon, Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalila and Delibes’ Lakmé. At the same time, the influence ofRichard Wagner was felt as a challenge to the French tradition. Many French critics angrily rejected Wagner’s music dramas while many French composers closely imitated them with variable success. Perhaps the most interesting response came from Claude Debussy. As in Wagner’s works, the orchestra plays a leading role in Debussy’s unique opera Pelléas et Mélisande (1902) and there are no real arias, only recitative. But the drama is understated, enigmatic and completely unWagnerian.

Other notable 20th century names include Ravel, Dukas, Roussel and Milhaud. Francis Poulenc is one of the very few post-war composers of any nationality whose operas (which include Dialogues des Carmélites) have gained a foothold in the international repertory. Olivier Messiaen’s lengthy sacred drama Saint François d’Assise (1983) has also attracted widespread attention.