3.1: Background Time

- Page ID

- 91136

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)To find the background time in any piece of music tap your hand or nod your head or move in whatever way allows you to match the music. If this is a consistent pulse then it is most likely the background time. The background time is a pulse or beat around which other rhythms are organized. A pulse or “beat” happens when there are regular equal-length durations. A metronome is a tool that provides a pulse at specific beats per minute (BPM). In some genres/cultures there is an aesthetic for strict adherence to metronomic pulse. In some music the preference is to let the pulse push or pull. Modern popular music that utilizes computers for performance or “tracking” would most often be metronomic. “Tracking” refers to performing on a live instrument while staying with a digital track that keeps both audio and visual aspects of the song steady, choreographed and synchronized. This could range from the music of Bollywood, hip-hop, electronic dance music (EDM) and American country. Some people prefer for the beat to “push and pull” (slightly speed up or slow down) as the artist is feeling the music. This can be heard in Hindustani music, Western art music, and classic rock. Often the shift in speed/tempo is so subtle that it is not noticeable to the untrained ear.

The background pulse sets the tempo of the music. Tempo refers to the speed of the background pulse in music. In the Western musical world Italian terms are utilized to describe music because composers traveled to Italy to study Opera composition for two centuries (1600s-1700s). Other Italian terms used when considering a background pulse are:

|

Accelerando |

gradually speeding up |

|

|

Ritardando |

gradually slowing down |

|

|

Ritard |

slow down |

|

|

Presto |

very fast |

|

|

Allegro |

fast and lively |

|

|

Andante |

at a walking pace |

|

|

Adagio |

slow and stately |

|

|

Grave |

very slow |

In “classical” music that is absolute (see Module 1 for definition of absolute) the tempo indications are often given in lieu of titles for the movements of a multi- movement genre (symphony, string quartet, concerto, sonata). For example, Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 14, Opus 27 No. 2 (Moonlight Sonata) has three movements. In a program the piece would be listed with the movement titles as tempo indications.

Piano Sonata No. 14, Op. 27 No. 2 \(\ \quad\quad\quad\)Beethoven, Ludwig van

- Adagio sostenuto (slow and sustained)

- Allegretto (moderately fast)

- Presto agitato (very fast and agitated)

Another example of this would be the String Quartet, Opus 11 written by American composer Samuel Barber in 1936-43. This work has four movements listed:

String Quartet, Op. 11 \(\ \quad\quad\quad\)Barber, Samuel

- Molto allegro e appassionato (very fast and passionate)

- Molto adagio (very slow)

- Molto allegro (very fast)

The success of this work is widely attributed to the second movement. Barber arranged this movement as a stand alone work for a larger string orchestra. It is entitled Adagio for Strings. In a world of descriptive titles this title might seem too minimal but it effectively allows the listener to bring their own meaning to this slow piece for strings.

When the background pulse of a work speeds up and slows down in an effort to express emotion this is referred to as rubato. Rubato is dramatic and intentional and is generally associated with dramatic emotional expression that became an important aesthetic for Romantic era performance of Western Art Music. The piano music of Frédérick Chopin is often associated with this rhythmic practice.

Another Western Art technique that frees the performers to interpret tempo in a loose way is associated with Opera. In opera when composers must advance the plot through the presentation of dialogue but do not wish to compose “songs” they use recitative. Recitative is singing that follows the natural flow of speech. In a recitative section of an opera or a cantata there is often much rhythmic freedom given to the performers.

When a piece has no consistent background pulse it is non-metric. Music without a discernable pulse can also be referred to as Free Rhythmic. From the perspective of those who listen primarily to American Pop genres this is not a common rhythmic approach. It is; however, evident in much music spanning many genres. Non-metric music can range from works performed on shakuhachi flute, Japanese gagaku, ambient music, aleatoric/chance music, sections of Balinese Gamelan, plainchant, recitative in Opera, sections of Indian classical music, and signaling music. While it is important to note that not all music has a steady pulse, all music has rhythm.

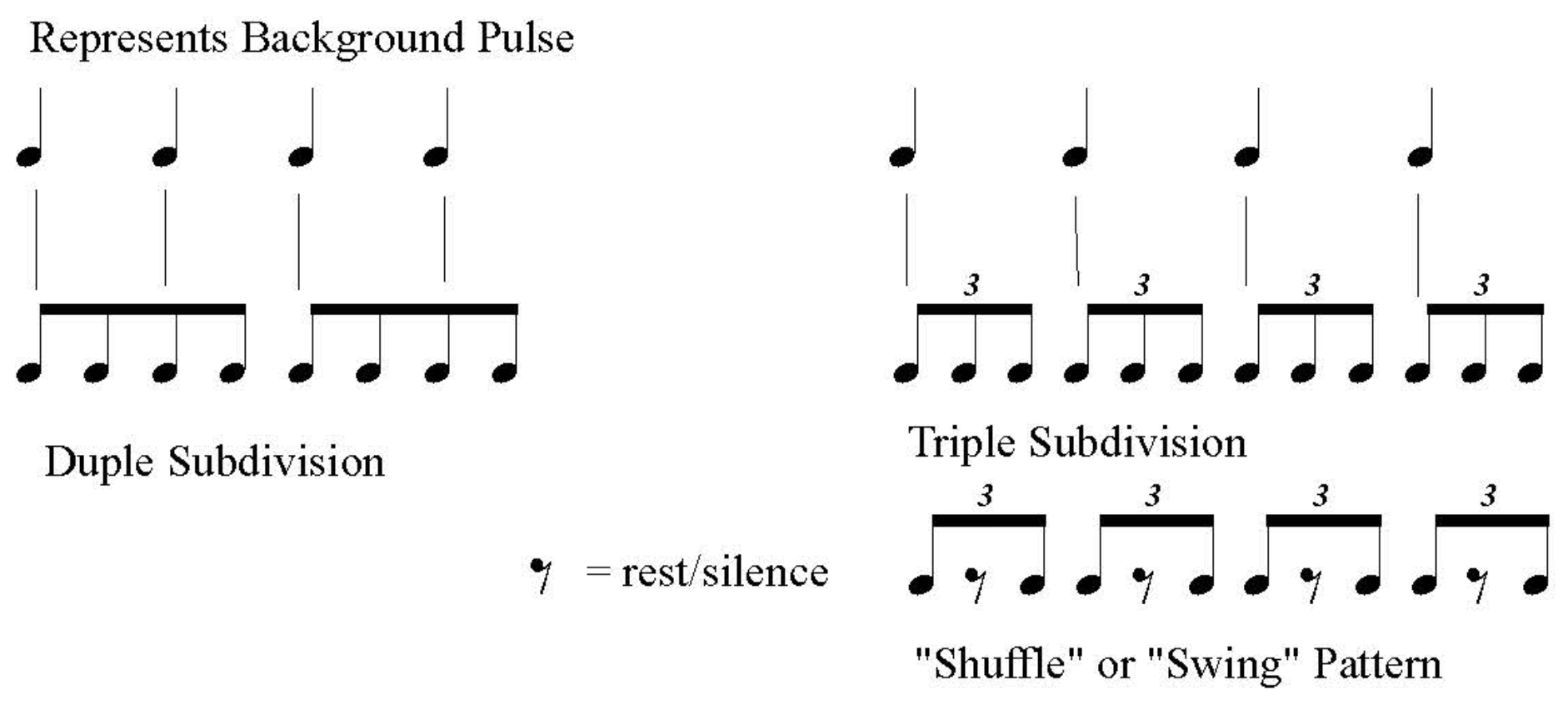

Another important aspect of the background pulse is the subdivision. The two most common subdivisions of the background pulse are duple and triple (see Figure 1). A duple subdivision of the background pulse divides the space between each beat evenly in two. In America the colloquialism to indicate a duple subdivision is to say that the music is “straight”. A triple subdivision of the background pulse divides each beat by three. The colloquialism for this approach is to say that the music “swings”. Most American pop music can be classified as “straight” or “swinging”. This simply refers to a duple or triple subdivision of the background pulse. Each approach has a “feeling”. Most American pop music prior to the 1950’s “swung” or had a triple subdivision. From the 1960’s to present the aesthetic preference has been for music that is “straight”. The aesthetic pendulum will, no doubt, swing back to “swing” someday.