10.4: Carl Orff - Carmina Burana

- Page ID

- 90742

Although popular song has been the preferred political vehicle of the past century, art music is also ripe for exploitation. Indeed, much of the music that we enjoy in concert halls and opera houses today was created on behalf of political regimes for the purpose of cementing their power. Monteverdi’s opera Orpheus, for example, was intended to display the wealth of the Gonzaga court and solidify its position in the eyes of visitors. Although the plot of Orpheus is not explicitly political, many of the Italian operas of the following two centuries portrayed monarchs as benevolent and wise father figures ordained by God for the safekeeping of their people— an image that did much to mediate potential unrest. The modern symphony orchestra, in its own turn, might be traced to a court in Mannheim, where an orchestra was used to advertise the splendor of Charles III Philip, who ruled a large region in what is now Germany.

Orff and the Nazi Party

Here, however, we will examine a 20th century instance of concert music turned to political use. While Carl Orff (1895-1982) did not set out to write a political piece of music, his scenic cantata Carmina Burana was embraced by the Nazi Party, the leaders of which believed that it conveyed many of their values and could be put to use for the purpose of riling up crowds and building communal sentiment. Beginning in 1940, Carmina Burana was frequently performed at Party rallies and government functions, in which context it both exemplified “good” Nazi music and was used to boost enthusiasm for the government and its activities.

Carl Orff was not himself a member of the Nazi Party. After the war, he was investigated by the American denazification authorities, who cleared him of collaboration charges and authorized him to continue his professional work. All the same, Orff thrived under the Nazi regime, and he certainly didn’t use his position of relative influence to resist the regime’s activities. He never denied the Nazis permission to use his work, and on several occasions actually wrote music on their behalf. Any attempt at subversion, of course, would probably have culminated in Orff’s execution. In short, he behaved as many Germans of the era did, neither supporting nor condemning the Nazis.

Orff wrote a large number of theatrical works, many of which expressed his theory of “elemental music.” In attempting to recapture the power of ancient Greek drama, Orff advocated for a unified stage art that combined music, dance, poetry, image, design, and theatrical gesture. If this sounds familiar, we have already seen other creative figures attempt to revive the arts of ancient Greece (the Florentine Camerata, discussed in Chapter 4) and develop an all-encompassing approach to musical theater (Richard Wagner, discussed in Chapter 3). Indeed, Orff himself was responsible for the 1925 revival of the most famous opera produced under the Camerata’s influence, Claudio Monteverdi’s Orpheus. His greatest impact, however, was in the field of music education. He co-founded the Günther School in Munich in 1924 and taught music there until the end of his life. The techniques he developed for working with young children are still in use today.

Carmina Burana

Carmina Burana—certainly Orff’s most successful composition—is what he termed a “scenic cantata.” A cantata is a multi-part work for voice(s) and accompaniment. We examine two cantatas elsewhere in this volume: Barbara Strozzi’s Lagrime mie for solo soprano and basso continuo (Chapter 8) and Johann Sebastian Bach’s Sleepers, Wake for soloists, choir, and orchestra (Chapter 11). Cantata, however, is a flexible designation. Just as Strozzi and Bach’s cantatas have little in common, Orff’s cantata will in turn bear only a limited resemblance to other cantatas you might have encountered. His addition of the term “scenic” indicates that his cantatas are meant to be staged. Orff envisioned dramatic performances complete with sets, costumes, pantomime, and dancing. Carmina Burana was indeed presented as a dramatic spectacle in its early days, although now you are more likely to encounter it as an unstaged concert work.

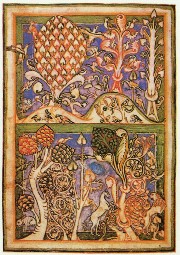

Today, Carmina Burana seems to have completely shed its wartime significance. Few people know that it was ever used as Nazi propaganda, and it is widely enjoyed by audiences and performers. This is in part possible because the text has nothing whatsoever to do with politics, war, or Nazi values. Indeed, the text is nearly a thousand years old: Orff extracted it from a medieval manuscript of the same name. “Carmina Burana” is Latin for “Songs from Benediktbeuern,” and refers to a volume of poems written primarily in the 11th and 12th centuries. The manuscript containing the poems was discovered at a Benedictine monastery in Benediktbeuern (now a municipality in Bavaria) and is prized as one of the most significant collections of what are known as goliard songs.

Goliards were, in modern terms, carousing college dropouts. Many were younger sons from wealthy families. Because only the eldest son could inherit, younger sons were sent to monasteries or Catholic universities, where they were educated in theology and prepared to enter the clergy. Many of these young men, however, had no affinity for the religious life and instead preferred to pursue more earthly pleasures. Because they had been well educated, goliards were able to leave a record of their satirical poems and racy songs. Most of these were written in Latin, the language of the Catholic church, although some are in the vernacular languages spoken by the goliards.

The songs in the Carmina Burana manuscript address all of the topics that might be of interest to young men who enjoy having a good time: the fickleness of fortune and wealth, the ephemeral nature of life, the joy of the return of Spring, drinking, gluttony, gambling, and lust. Few of the texts can be associated with specific melodies, meaning that a composer who wanted to borrow them would be obliged to create new musical settings. Orff did so, although he often sought to imitate the melodic shapes and modes of Gregorian chant (see Chapter 11 for an example).

Taken as a whole, however, Orff’s music is far removed from that of the medieval Catholic church. He wrote for an enormous ensemble consisting of three vocal soloists, three choirs (two mixed and one boys’), and a large orchestra complete with an eighteen-piece percussion section and two pianos. His music was inspired by Igor Stravinsky’s primitivist ballets (see Chapter 3), which used repetitive melodic figures (ostinatos) and jarring rhythms to evoke a pre-modern social order.

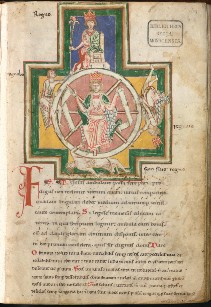

To create his scenic cantata, Orff first chose twenty-three poems from the manuscript and organized them into scenes, which address the topics of fate, springtime, drinking, and love. The first and last scenes are identical, for they portray “Fortune, Empress of the World.” The vision of fortune as a great wheel that turns incessantly can be found throughout the Carmina Burana manuscript, where it is represented both in verse and image. It therefore seemed natural to Orff that his cantata should end as it had begun, with a mighty chorus announcing the power of fate to shape our lives. We will examine four musical selections, one representing each of the four themes explored in Carmina Burana.

“O Fortune”

The opening chorus, “O Fortune,” is certainly the most famous part of Carmina Burana. It has featured in dozens of films, television shows, commercials, and video games, and has even been employed by professional sports teams. Its text consists of three stanzas:

|

“O Fortune” from Carmina Burana. 6. Composer: Carl Orff. Performance: Orchestra and choir of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, conducted by Eugen Jochum (1968) |

O Fortune, like the moon of ever changing state, you are always waxing or waning; hateful life now is brutal, now pampers our feelings with its game; poverty, power, it melts them like ice.

Fate, savage and empty, you are a turning wheel, your position is uncertain, your favour is idle and always likely to disappear; covered in shadows and veiled you bear upon me too; now my back is naked through the sport of your wickedness.

The chance of prosperity and of virtue is not now mine; whether willing or not, a man is always liable for Fortune’s service. At this hour without delay touch the strings! Because through luck she lays low the brave, all join with me in lamentation!

Translation by Gavin Betts. Used with permission.

The music is simple in the extreme. After a shockingly loud introduction, in which the full chorus and orchestra sound a series of accented chords, the instruments of the orchestra set an ostinato into motion. The ostinato contains only four pitches, each of which is sharply accented. Over the top of this ostinato, the chorus sings a melody constructed out of repeated melodic and rhythmic fragments. Almost all of the melodic motion is conjunct and the entire melody occupies the tiny range of a fifth. Some commentators have compared this melody to Gregorian chant, while others have remarked upon its folk-like qualities.

The first two verses are musically identical, but the third is marked by an explosion in volume. The sopranos repeat their melody, but they do so an octave higher than before. Likewise, high-register instruments join the ostinato. In the final moments of the movement, the pattern finally breaks as a new six-note ostinato takes us to the final thrilling chord. Orff’s music certainly conveys the power and inescapability of fate!

“Dance”

The next selection we will consider has quite a different mood. It is an instrumental movement from the springtime scene entitled simply “Dance.”7 All the same, “Dance” shares a great deal in common with “O Fortune.” Orff opens the movement with a series of dramatic chords, after which he uses ostinatos to underpin a melody that is itself full of melodic repetition. And once again, that melody moves primarily by step and occupies only a small range. “Dance” feels a bit more rhythmically unpredictable than “O Fortuna.” This is due to the fact that the meter changes frequently, which prevents a steady pulse from being established (try tapping your toe along to the music—it should be very difficult). A further sense of liveliness is produced by metric disagreements between the ostinato and the melody: Often, the strong pulses in each layer do not line up.

|

“Dance” from Carmina Burana. 7. Composer: Carl Orff. Example: Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Donald Runnicles (2002) |

“Dance” is in a ternary (A B A) form. The first A section features strings, which composers often employ to bring pastoral scenes to life. The flute, which carries the melody in the B section, is even better suited to shepherd life. This middle passage is unusual, for we hear only the flute and timpani—a rare paring to be sure. Finally, the A melody returns in the horns and trumpets. As in “O Fortune,” the music builds to an exciting and noisy final chord.

“Once I had Dwelt on Lakes”

Our third example will provide still further contrast, for it features one of the humorous texts that Orff chose to include in his cantata. “Once I had Dwelt on Lakes”8 is narrated from the perspective of a roast swan as he awaits his fate on a banquet table:

|

“Once I had Dwelt on Lakes” from Carmina Burana 8. Composer: Carl Orff Performance: Gerhard Stolze, Orchestra and choir of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, conducted by Eugen Jochum (1968) |

Once I had dwelt on lakes, once I had been beautiful, when I was a swan. Poor wretch! Now black and well roasted!

The cook turns me back and forth; I am roasted to a turn on my pyre; now the waiter serves me. Poor wretch! Now black and well roasted!

Now I lie on the dish, and I cannot fly; I see the gnashing teeth. Poor wretch! Now black and well roasted!

Translation by Gavin Betts. Used with permission.

Each of the three stanzas concludes with a refrain, which is sung by the men of the choir. The part of the swan is played by the tenor soloist, who sings at the top of his range. The resulting sound, which is often tense and pinched, can be heard as an imitation of the swan’s own voice. We also hear the swan in the opening bassoon solo—played at the top of that instrument’s range. Finally, the fluttering sound in the strings and flute might capture the swan’s trepidation as he contemplates his impending fate. Once again, repetitive melodies—melodies that are also, in the case of that sung by the choir, stepwise and limited to a narrow range—are underpinned by ostinatos.

“It is the Time of Joy” & “Sweetest of Men”

Finally, we will examine a selection—or, to be fair, a pair of selections—from the scene dealing with love. We are not talking about romantic love, however, but carnal lust. The texts to “It is the Time of Joy”9 and the short response number “Sweetest of Men”10 outline the courtship of a woman by a young man who is consumed with desire. She ultimately accedes:

|

“It is the Time of Joy” from Carmina Burana Composer: Carl Orff 9. Performance: Gundula Janowitz, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Orchestra and choir of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, conducted by Eugen Jochum (1968) |

|

“Sweetest of Men” from Carmina Burana 10. Composer: Carl Orff Performance: Gundula Janowitz, Orchestra of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, conducted by Eugen Jochum (1968) |

It is the time of joy, O maidens, now enjoy yourselves together, O young men. Refrain: Oh, oh, I am all aflower, now with my first love I am all afire, a new love it is of which I am dying.

I am elated when I say yes; I am depressed when I say no. Refrain

In the time of winter a man is sluggish, when spring is in his heart he is wanton. Refrain

My innocence plays with me, my shyness pushes me back. Refrain

Come, my mistress, with your joy; come, come, fair girl, already I die. Refrain

Sweetest of men,

I give myself to you wholly!

Translation by Gavin Betts. Used with Permission.

This musical example is dominated by percussion and piano, which keep up a lively rhythmic accompaniment. The verses are sung alternately by the women and the men of the choir, while the refrain is sung alternately by the baritone soloist and the boys’ choir. The complete vocal forces come together for the final verse/refrain pair. Every pair is sung to the same melody, but the timbral variations introduced by the changes in singers keeps the music from getting stale.

“Sweetest of Men” could hardly be more different from “It is the Time of Joy.” In place of the percussive ostinatos, the orchestra sustains a single harmony. The solo soprano soars to the top of her range, carrying the fifth vowel of her text through a long passage of notes. This is known as a melismatic passage, and it contrasts sharply with the syllabic character of the previous number, in which every syllable was paired with a single note. The selection can be heard in fairly graphic terms as the satisfying fulfillment of a sexual encounter, which was communicated by all the bumps and bangs of the previous number.

This particular moment almost got Orff into trouble with the authorities, for the Nazi regime did not take kindly to the glamorization of improper social behaviors. (The Soviet regime was equally prudish, as exemplified by its response to Dmitri Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsenk District, which is detailed in the final section of this chapter.) In fact, Herbert Gerigk, a leading ideological voice in the Nazi Party, registered several objections to Carmina Burana when he reviewed the premiere: He found fault in the language of the text, which was incomprehensible to German listeners; the primitive character of the music, which he considered to reflect the influence of jazz (a musical style that was widely denigrated and strictly forbidden); and the “loose morals” on exhibit in the cantata. Nonetheless, it was another interpretation of Carmina Burana that won official acceptance. The Nazi official Horst Büttner regarded the work as exemplifying “the radiant, strength-filled life-joy of the folk.” He also pointed out that the poems were artifacts of German folk heritage, and therefore to be treasured as national literature. Finally, Büttner connected the rhythms and melodies with German folk music, thereby identifying Carmina Burana as an authentic expression of German identity. When used in the context of political gatherings, Carmina Burana had the added value of encouraging powerful and unambiguous collective emotional reactions. It seemed to echo Hitler’s call for Germans to “think with your blood.”

This was the kind of music that could inspire support for the regime on a purely physical level.