10.2: Music as Political Advocacy

- Page ID

- 90740

Campaign Songs

The use of music to rally support for a political cause has a long history. Music has been used around the world to display the power of monarchies, to urge soldiers into battle, and to inspire patriotic support for all manner of governments. Here, we will focus on the role of music in American politics, with special attention given to specific songs that have been used by candidates seeking election to the presidency. Although we are focusing on campaign songs, those are not the only musical tools that have been employed by American political candidates. Before the rise of mass media, campaigning was conducted in person at events such as rallies, parades, and whistle stops, often to the accompaniment of a local brass band playing popular and patriotic tunes. Today, we are more likely to hear campaign music via television, whether we are watching a televised campaign event or a paid political advertisement. At events, candidates are likely to use popular songs that convey a relevant message, set the right mood, or speak to a desired voting base. In advertisements, we are more likely to hear underscoring similar to that used in television shows and movies. Such music attracts less attention than a popular song, but it plays an equally important role in communicating the candidate’s message.

In this 2016 campaign ad for Georgia gubernatorial candidate Casey Cagle, the music is bouncy and cheerful.

To see underscoring at work, we might examine two recent television advertisements from a 2016 Republican candidate for governor of Georgia, Casey Cagle. In a spot from early in the campaign, titled “Difference,”1 Casey touts his humble beginnings, strong personal ethic, and political accomplishments. The music behind his voiceover is bouncy and cheerful. The major mode tells us that this is a message of optimism, while the mid-tempo drumbeat and repetitive, staccato melody notes are reassuring and uplifting. Later in the campaign, however, Cagle— in response to a strong showing by his rival—attempted to construct a new public persona for himself, one that emphasized strength and determination. These qualities are reflected in the television advertisement “About,”2 which features music that would be equally at home in an action film. The minor mode and suspenseful harmonies keep the listener on edge, while periodic percussive strikes suggest danger and unrest. As musicologist Naomi Graber has observed, the music builds to a climax in parallel with Cagle’s rousing speech, suggesting that Cagle himself is the superhero in this narrative.

In this ad from later in Cagle’s campaign, the music is suspenseful.

Candidates are sometimes musicians themselves and are therefore able to exploit their own musical skills to win the sympathy and support of the public. In 1886, for example, two brothers—Alf and Bob Taylor—ran against one another in a bid to become governor of Tennessee. Both men were excellent fiddlers, and they not only performed frequently throughout the campaign but also used their love of folk music to establish a down-home identity and connect with rural voters. More than a century later, President Bill Clinton advertised himself as fun-loving and cool by playing saxophone on The Arsenio Hall Show, while Democratic presidential candidate Martin O’Malley garnered attention by playing guitar and singing Taylor Swift’s “Bad Blood” on The View. Although the genres (and skill levels) of these candidate-performers varied widely, all used music to paint themselves as good-humored and relatable.

When it comes to conveying a specific political message through music, song is clearly the best choice, and it has been in use since the beginning of American electoral politics. In the earliest years, election songs were usually parodies. As early as George Washington’s reelection campaign in 1792, supporters advocated their candidates’ causes by writing new words to recent popular songs. This technique could be very effective. Because the melody was already familiar, parody lyrics were quickly learned, sung, and spread. The success of a popular song could even contribute to the success of the campaign that chose to parody that song. In 1840, William Harrison’s campaign song “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too,” which parodied the familiar “Three Little Pigs,” became so popular that it was widely credited with winning him the presidency.

There is also a long history of presidential candidates relying on endorsements by celebrity musicians to boost their popularity. The earliest example of this came in 1860, when the famous abolitionist singer Jesse Hutchinson wrote a parody song in support of Abraham Lincoln. The song—”Lincoln and Liberty, Too,” set to the tune of “Rosin the Beau”—was a hit, but Hutchinson’s popularity probably contributed just as much to Lincoln’s victory.

New songs have also been written in support of presidential candidates. While this practice dates to the early 20th century, it is particularly widespread today, when anyone can write a song, record a performance, and upload their contribution to social media. Technology has always influenced the role of music in presidential elections. Beginning in the 1930s, the prevalence of radio (and later television) led campaigns to employ songs that were already popular—an approach that proved more effective than the creation of a new song that might or might not prove a hit. In this chapter, we will consider three such songs. These songs are all quite different in style and message, but they share one important thing in common: None of them were written with any political end in mind. In each case, the presidential campaign coopted the song because it supported the campaign’s political message.

Milton Ager and Jack Yellen, “Happy Days Are Here Again”

The first presidential candidate to coopt a popular song for his campaign was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who in 1932 adopted the recent hit song “Happy Days Are Here Again”3 to represent his political agenda. Although the song was not created for his campaign and did not communicate an explicitly political message, Roosevelt found that it perfectly captured the spirit of his presidential bid.

|

“Happy Days Are Here Again” 3. Composers: Milton Ager and Jack Yellen Performance: Annette Hanshaw (1930) |

It is no surprise that Roosevelt should have been the first presidential candidate to use a popular song in his campaign. The 1920s and 1930s were a time of extraordinary growth in the music recording and broadcast industries, with the result that popular songs were more influential than ever before. The first commercial license was issued to a radio station in 1921, while 1925 saw the invention of the electrical microphone and an accompanying improvement in the quality of recorded and broadcast sound. Due in part to the economic downturn of 1929, radio soon eclipsed the phonograph in popularity. The most successful programming in that era consisted of live musical performances. Roosevelt was the first presidential candidate (and later president) to take full advantage of the radio as a platform for connecting with Americans and spreading his message.

The decision to play “Happy Days Are Here Again” at the 1932 Democratic National Convention was made spontaneously after the man who introduced Roosevelt gave a lifeless and dour speech. Roosevelt’s campaign managers had originally intended to brand him with “Anchors Aweigh” (a nod to his Navy service), but they felt that the occasion called for something more lively and selected “Happy Days Are Here Again” at the last moment. The song proved effective and was used for the remainder of the campaign. In fact, it was such a success that “Happy Days Are Here Again” was associated with the Democratic Party for many years to come.

In 1932, a song like “Happy Days Are Here Again” would have had particular resonance with Americans, who were experiencing the worst effects of the Great Depression. The 1930s saw a public clamor for escapist films, theater, and songs. Almost no popular songs from this era reference the difficulties that plagued Americans following the stock market crash of October 1929. Instead, they celebrate good times, affluence, and carefree living.

The authors of “Happy Days Are Here Again”— composer Milton Ager and lyricist Jack Yellen— were themselves the beneficiaries of fortunate timing, for they wrote their song just before the onset of the Great Depression. “Happy Days” was commissioned by MGM for inclusion in an early sound film, Chasing Rainbows (1930). While waiting for the film to be released, however, Ager and Yellen provided their new song to bandleader

George Olsen, who performed regularly at Hotel Pennsylvania in New York City. Olsen’s band premiered “Happy Days” on October 24, 1929—the day of the crash. Olsen supposedly called on his soloists to “sing it for the corpses,” a reference to the morose diners who had just lost their life savings. As Yellen recalled, “After a couple of choruses, the corpses joined in, sardonically, hysterically. Before the night

was over, the hotel lobby resounded with what had become the theme song of ruined stock speculators as they leaped from hotel windows.” “Happy Days Are Here Again” went on to become a major hit. It appealed to listeners who reveled in the irony of the lyrics (“happy days” were certainly not anywhere to be seen), but it also embodied the American spirit of optimism and perseverance in the face of extreme difficulty. The lyrics—like those of most successful songs—are not about any particular event or situation. Instead, they speak in broad terms, bidding farewell to “sad times” and “bad times” before celebrating the fact that “the skies above are clear again” and calling on all to “tell the world” that “happy days are here again.”

“Happy Days Are Here Again” was a project of a songwriting industry known as Tin Pan Alley. The main product of Tin Pan Alley song publishers was sheet music, which consumers would purchase so as to be able to perform hit songs in their own homes. By 1929, sheet music sales had already been eclipsed by phonograph sales, and radio was further eating into the popular music market share. Still, songwriting teams, usually in the employment of Tin Pan Alley publishers, continued to crank out potential hits into the 1940s. (The name “Tin Pan Alley” refers to the discordant sounds of cheap pianos being played in the many publishing houses located on a single block in Manhattan.)

During the Tin Pan Alley era, songs were not often associated with individual performers. Instead, hit songs were recorded by all of the prominent singers, each of whom was expected to perform a common repertoire. “Happy Days Are Here Again” was first recorded in November 1929 by Leo Reisman and His Orchestra, but this was only the first in a parade of renditions by a variety of popular singers. We will consider the 1930 recording by Ben Selvin and His Orchestra, with Annette Hanshaw on vocals.

Ben Selvin (1898-1980) holds the honor as the most productive recording artist in American history, having recorded as many as 20,000 individual tunes. It is difficult to make an exact count because Selvin recorded under dozens of different names for all of the major record

labels of his era. This was a typical practice, since performing artists were required to sign exclusive contracts with recording companies. The use of pseudonyms allowed an artist to triple or quadruple their income by recording with a variety of labels. As a producer at Columbia Records, Selvin also oversaw the creation of recordings by other artists. His catalog includes some of the finest records made in the early 1930s.

Annette Hanshaw (1901-1985) was among the countless singers who performed and recorded with Selvin’s band. She was also very famous in her own right, being voted the best female popular singer in a 1934 Radio Stars magazine poll. Hanshaw, however, later confessed that she detested performing and could not stand her own records. She loved music but became very nervous in front of a microphone and was dissatisfied with her abilities as a singer.

Selvin and Hanshaw’s recording of “Happy Days Are Here Again” is typical of 1920s-era sweet jazz. This type of music was intended primarily for dancing, and it could be heard in upscale urban hotels, ballrooms, and on the radio. Selvin’s band contains instruments that we associate with jazz today, such as saxophones, trumpets, trombones, and piano, but—in keeping with the standard of the era—it also contains a violin section, and the bass line is played on the tuba instead of the string bass. The tempo is lively and the beat is clearly articulated by the rhythm section (piano and tuba).

Ager and Yellen’s jazz-influenced tune is highly syncopated, meaning that melody notes often fall between beats. We can hear this in the chorus: The word “happy” falls on the beat, but the words “days” and “are” come after the beat. (Try clapping the pulse while reciting the lyrics in rhythm to see how this works.) This pattern is repeated with the next phrase, in which “here” falls on the beat but the second syllable of “again” come off the beat. Selvin’s band makes this pattern sound even more exciting by shortening the melody notes that fall on the beat.

The form of this recording is also typical of the era. Although the song “Happy Days Are Here Again” technically begins with a verse, Selvin chooses to open his rendition with the much catchier chorus. After singing through the chorus once, Hanshaw sings the verse, which is much shorter than the chorus and also in the minor mode. This provides welcome contrast, but the change in mood doesn’t last long. Next, we hear a rendition of the chorus by an anonymous trio of male singers. Finally, we get an instrumental version, with the male singers joining in for the closing phrase. In short, most of the recording is taken up by three complete turns through the chorus—which, by the end of the three minutes, is firmly lodged in the listener’s head.

This approach to the production of popular music—extreme repetition, softened by a brief excursion into contrasting material—is still with us today. Although the forms, sounds, and lyrics have all changed, record producers continue to foreground the most memorable musical material while finding opportunities to introduce contrast. This delicate balance between too much repetition (which would make a song annoying) and too little (which would prevent it from being memorable) characterizes the eternal formula for successful popular music.

Paul Simon, “Bridge Over Troubled Water”

Successful campaign songs always combine a relevant text with music that sets an appropriate emotional tone. It is easy to see how a song like “Happy Days Are Here Again” could serve this purpose well: It is bright and cheerful, and exhibits unchecked optimism about the future. The 1970 Simon & Garfunkel hit “Bridge Over Troubled Water”4 is a less obvious choice for a political campaign. While the song’s lyrics touch on themes that a candidate might want to emphasize, the music lacks the energy of a typical campaign song. We will begin, therefore, by examining the song itself. Then we will consider why George McGovern, the Democratic challenger to President Richard Nixon, might have selected it for his 1972 campaign.

|

“Bridge Over Troubled Water” 4. Composer: Paul Simon Performance: Simon and Garfunkel (1970) |

In 1969, Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel were two of the biggest stars in American popular music. Their recent albums Sounds of Silence (1966) and Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme (1966) had both proved major hits, and they were at the forefront of the folk rock genre. Although both men sang and made contributions to the duo’s arrangements, Simon was the lead songwriter—a fact that caused some friction, as Simon increasingly felt that Garfunkel was not making an equal contribution to the partnership. The duo broke up in 1970 just as their fourth album, Bridge over Troubled Water, was rapidly climbing the charts.

Simon wrote “Bridge over Troubled Water” very quickly in 1969. He later recounted that the basic idea took him about twenty minutes to work out, while the whole song was finished in under two hours. The title lyric was inspired by a line from the 1958 Swan Silvertones song “Mary Don’t You Weep,” in which Claude Jeter sings, “I’ll be your bridge over deep water if you trust in me.” Simon’s source ended up shaping not only the lyrics but the sound of his new song. The Swan Silvertones were an African American gospel group, and their music drew from the rich tradition of black church music. Although Simon and Garfunkel did not attempt a wholesale imitation of this style, they wanted their recording to reflect the influence of gospel (a style discussed in Chapter 11).

“Bridge over Troubled Water” contains three verses, the last of which was added at the request of Garfunkel to support the song’s dramatic musical climax. Simon wrote the verse, but never cared for it—his message was communicated in its entirety in the first two verses. These vow to the listener that, although they may be “weary, feeling small,” “down and out,” or “on the street,” the singer will always “take your part” and “lay me down / Like a bridge over troubled water.” In short, the song promises solace and support for anyone who is experiencing difficulties in life.

Although Simon wrote the song using his favored instrument, the guitar, he chose to make the recording with a piano played in the gospel style. The instrumental introduction, with its grandiose chords and syncopated rhythms, could indeed preface the entrance of a gospel singer. Instead, we hear the voice of Garfunkel, which Simon thought was better suited to the tune than his own. The first verse is accompanied only by piano. The second verse is additionally supported by vibraphone, which adds warmth and resonance without changing the character of the song.

At the conclusion of the second verse, however, the music takes a new direction. First, a drum set crashes onto the soundscape. Strings enter next, followed by an electric bass. The full instrumental forces grow in energy throughout the third and final verse, which also features Simon singing a harmony part. In the final seconds of the song, the tempo slows as the strings ascend to their highest note, producing a triumphant conclusion.

Despite the drama that Simon and Garfunkel were able to produce in their studio recording of “Bridge over Troubled Water,” the song itself is not particularly energetic. It features a slow tempo, a sustained vocal line, and lyrics that encourage the listener to feel calm and resolute. It’s not a song one would play to rile up a crowd or to encourage enthusiastic support for a cause.

All the same, George McGovern chose “Bridge over Troubled Water” as the theme song for his 1972 presidential bid, and he played it at his rallies throughout the campaign. The song certainly embodied many of McGovern’s values. He ran on a platform of national unification and healing, advertising his ability to reach across the aisle and bring opposing factions together. The preceding years had indeed been characterized by devastating internal conflict, including the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., the 1969 Stonewall riots, and growing unrest concerning the war in Vietnam—unrest that culminated in the 1970 Kent State massacre in which National Guardsmen killed four student protesters. McGovern positioned himself as a staunchly anti-war candidate who would bring peace to the nation. For this reason, “Bridge over Troubled Water” was uniquely suited to his campaign. At one point, McGovern even quoted the song directly, stating, “I want, indeed, to become a bridge over troubled waters.”

McGovern was able to use “Bridge over Troubled Water” in another way as well. He invited Simon and Garfunkel to participate in a benefit concert that took place in Madison Square Garden on June 14, 1972. (Simon actively supported McGovern’s candidacy; Garfunkel was less enthusiastic but eager to perform before a large crowd.) McGovern naturally benefitted from having star performers take the stage, just as he profited from associating himself with a song that was heard constantly on the radio. However, McGovern was also able to polish his image by bringing the sundered duo back together for the first time since their partnership had ended. He, after all, was the candidate of reconciliation and peace making. McGovern’s ability to restore the Simon and Garfunkel partnership therefore attested to his potential skills as a national leader.

“Bridge over Troubled Water,” therefore, was perhaps not as bizarre a choice for a campaign song as one might think. Unfortunately for McGovern, the song does not seem to have done him any good: He was soundly defeated in the 1972 election by incumbent Richard Nixon, who won over 60% of the vote and took every state except Massachusetts and the District of Columbia.

Tom Petty and Jeff Lynne, “I Won’t Back Down”

In contrast with Simon and Garfunkel’s soulful ballad, Tom Petty’s 1989 hit “I Won’t Back Down”5 is an obvious choice for a political candidate. In fact, it is so well-suited to the campaign trail that half a dozen candidates have employed it in just the first two decades of the 21st century. It was also used to voice a non- partisan political message following the September 11 terrorist attacks. At the same time, at least one candidate’s attempt to coopt the message and popularity of “I Won’t Back Down” backfired. We will try to understand why this song has been so useful in the context of political discourse and consider the risks of coopting the creative work of a celebrity for partisan purposes—especially when that celebrity is politically active.

|

“I Won’t Back Down” 5. Composer: Tom Petty and Jeff Lynne Performance: Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers (1989) |

By the time he released “I Won’t Back Down,” Tom Petty (1950-2017) was already a rock music superstar. Petty was born and raised in Gainesville, FL, where he dropped out of high school to join a band. He was inspired by Elvis Presley and The Beatles, whose success proved to him that it was possible for a regular, working-class kid to make it in music. Although Petty only achieved local celebrity in his first decade as a rock musician, the late 1970s saw the meteoric rise of his band Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, which recorded a string of successful albums between 1976 and 1987. Although the Heartbreakers would reconvene in the early 1990s and continue to release albums until just a few years before Petty’s 2017 death, Petty took a hiatus in 1988 to join George Harrison’s group the Traveling Wilburys.

During this same period, Petty also released his first solo album, Full Moon Fever. The lead single from this album was “I Won’t Back Down.” Half of the songs on Full Moon Fever were cowritten by Tom Petty and Jeff Lynne, an English musician and founding member of the Traveling Wilburys. It is common for popular songwriters to work in pairs. This strategy has proved successful since the early 20th century, when Tin Pan Alley songwriters teamed up to produce hits. Many songwriters find that this approach aids productivity, since the contributors can help one another out of creative difficulties and suggest improvements to the music or lyrics. Lynne also produced the album and is, therefore, in part responsible for the sound of “I Won’t Back Down.”

The success of “I Won’t Back Down”—both as a popular song and as a political soundtrack—can be traced to its straightforward message. Like “Happy Days Are Here Again,” “I Won’t Back Down” does not refer to any particular event or circumstances. We don’t know what the singer is standing up for, or against whom he is resisting, or why he is in a position that requires he stand his ground. All we know is that, despite “a world that keeps on pushin’ me around” and “draggin’ me down,” the singer “won’t back down.”

The music admirably communicates this message of steadfast endurance. “I Won’t Back Down” is set to a medium rock tempo—not so fast as to feel frantic but not so slow as to feel lethargic. The music sounds as if it—like the singer— could carry on this way forever. The sung melody has a protracted melodic rhythm, meaning that the individual note values are long and unhurried. Petty’s unaffected drawl further convinces us that he is not to be moved, while the relaxed guitar solo underscores the point. “I Won’t Back Down” is, naturally enough, in the major mode, but the accompaniment prominently features a minor chord, heard under the word “won’t” in the title line. This tinges the lyric with seriousness of purpose. Although the singer is not overly concerned, he is not taking the threat lightly.

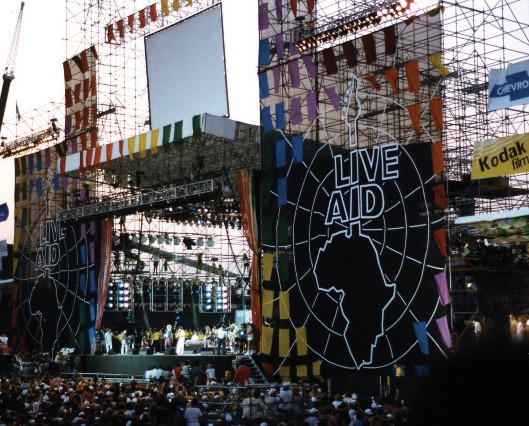

“I Won’t Back Down” first made political headlines in 2000, when George W. Bush used it at events during his presidential campaign. The song seemed an excellent choice, but it became a liability when Petty protested, sending the campaign a cease-and-desist letter and demanding that they quit using his music. Bush’s campaign staff might have known better: Petty had already indicated a penchant for political speech as a musician and had aligned himself with various activist causes. In 1979, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers performed in a Madison Square Garden concert intended to raise support for the dismantling of nuclear power plants, while in 1985 they took to the stage for the famous Live Aid concert in Philadelphia, which raised funds to combat famine in Ethiopia. And in 1992, Petty had written the song “Peace in L.A.” in response to the Rodney King riots, donating all proceeds to charity. Although none of these were explicitly left-wing causes, Petty was certainly aware of his power as a political agent, and he knew that music could make a difference in a political struggle. After the 2000 election, Petty performed “I Won’t Back Down” at Al Gore’s concession speech, thereby clearly sending the message that he intended to retain control over how his music was used.

Petty, however, did not always interfere when politicians coopted his music. During the 2008 presidential campaign, for example, “I Won’t Back Down” was used by Democratic candidates Hillary Clinton and John Edwards, but also by Republican candidate Ron Paul. In 2012, he again made no comment when “I Won’t Back Down” was played at the Democratic National Convention. That same year, however, he issued another cease-and-desist letter to Representative Michele Bachmann, who used his song “American Girl” to launch her presidential campaign. Petty, of course, was not the first rock star to object to the coopting of his hits—and also not the last. All modern presidential campaigns are accompanied by a chorus of popular recording artists asking that candidates stop using their music. It’s not clear why Petty accepted some uses of his songs and rejected others, but it is entirely clear that he understood the power of his music and celebrity.