4.2.4: Tian Han - The Tale of the White Snake

- Page ID

- 92113

Europe and the United States are, of course, not alone in developing sung drama traditions. Examples of musical drama can be found around the world. Here we will examine two, each of which has a unique set of characteristics and each of which—like European opera—requires years of dedicated training for those who desire careers as performers. Each of these traditions—also like European opera— is highly heterogeneous. Different styles and forms have dominated in different eras, and one can encounter a variety of contemporary practices.

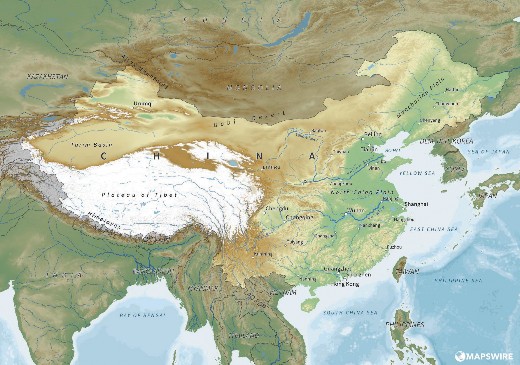

Beijing Opera

The form of musical theater known as Beijing opera is the most popular of the many forms of Chinese opera. Although the roots of Chinese opera extend back thousands of years, Beijing opera dates only to 1790—about when Mozart set to work on The Magic Flute. This particular form is said to have emerged when four regional opera troupes visited the Beijing court simultaneously to celebrate the 80th birthday of the Emperor. Although Beijing opera (like Italian opera) was available only as courtly entertainment for several decades, it soon found favor with the broader public, and by 1845 its conventions were both firmly established and widely enjoyed.

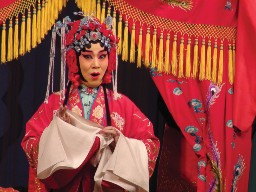

Beijing opera combines a variety of different art forms, and its practitioners must be well-versed not only in singing but also in gesture, dance, makeup application, and acrobatics. Traditionally, children were apprenticed to travelling troupes. They were offered little formal education, and were instead expected to learn through imitation. Today, this system has been replaced by formal schooling. Other changes have also shaped the tradition. Until the 1890s, all Beijing opera performers were men, many of whom specialized in female roles. When women first began to perform, they were confined to all-female troupes— some members of which, naturally enough, had to take on male roles. Troupes were integrated following the founding of the Republic of China in 1911, but men continue frequently to perform female roles, especially that of the beautiful young woman.

The roles in Beijing opera are highly standardized. There are four character types: Sheng (the lead male), Dan (any female), Jing (a forceful male), and Chou (the clown). Each character type has a variety of subtypes based on age and social status. An actor must specialize in playing a specific character type, for each has a distinct manner of speaking, singing, and moving. The Jing types also wear special face paint, the designs of which reveal facets of their character and mark them as being on the side of good or evil.

Many genres of Chinese music, including Beijing opera, are categorized into “civil” and “martial” works. Civil operas concern the court intrigues and love interests of the aristocracy, while

martial operas contain scenes of military conflict. Plots of both types are drawn from history, traditional stories, and novels, all of which are already familiar to the audience. A single opera will usually present only a few episodes from a much longer story, and it is typical to combine serious and comical elements.

Like the operas themselves, the orchestra that provides music for Beijing opera is divided into civil and martial instrument groups. The civil group contains string instruments.

The most significant of these is the jinghu, a high-pitched bowed fiddle after which the genre itself is named. The other principal instrument is the yueqin, a moon-shaped lute with four strings. The martial group—which might also be described as the percussion section—contains gongs of different sizes, cymbals, and a pair of instruments known as guban that consists of a high-pitched drum and a wooden clapper. These last are the most important, as they are played by the ensemble director. This person has a challenging task, for the percussion section must accompany action, punctuate speech, and provide sound effects—all of which requires precise timing. The orchestra might also contain additional lutes and wind instruments.

The division of the Beijing opera orchestra into string, wind, and percussion sections mirrors the European orchestra. However, there are significant differences both in the makeup of the ensemble and in its function. A Beijing opera orchestra usually contains only one player per instrument, and the music performed by the orchestra is heterophonic in texture, meaning that all of the instruments play the same melody, but not in perfect unison. Instead, each player interprets the melody in a way that is appropriate to the instrument, contributing ornaments or adding/removing pitches as considered suitable.

Beijing opera performances contain various types of orchestral and vocal music. None of this music, however, is composed for a specific opera. Instead, the melodies all belong to the tradition in general, and they are used by individual performers to characterize specific roles. Certain instrumental pieces, for example, are always played to accompany certain scenes, such as a banquet or the arrival of an important character. Onstage characters sing short arias in one of two modes: xipi for happy or energetic lyrics, and erhuang for serious or heroic lyrics. Each mode arranges the pitches of the pentatonic scale (degrees 1 2 3 5 and 6 of the major scale) in a different way, and the melodies in each tend to have different shapes.

For this reason, individual operas in this tradition do not have composers. The plots and dialogues are crafted by playwrights, but the music is drawn from a communal store. The same arias and instrumental numbers will be heard in a variety of different works. The singers themselves also have a great deal of control over the music, which will reflect their training, style, and vocal range. It is generally considered desirable to sing the arias as high as possible, so it is the onstage performers who determine what key the music will be in. While this level of flexibility will seem unusual to someone who is used to Western opera or musical theater, Beijing opera is in fact remarkably rigid when compared to other Chinese opera forms. The Shenqu opera of Shanghai, for example, can be completely improvised, with plots based on the news stories of the day.

The vocal timbre used in Beijing opera is one of its most remarkable features. Singers strive to produce a piercing, nasal sound with a slow, controlled vibrato. They will sometimes slide between pitches, each of which is carefully placed. The speech in Beijing opera is also highly stylized, and is often delivered in high range. To accomplish this, male actors frequently employ falsetto when singing and speaking. Actors employ an ancient dialect that is not always intelligible to modern listeners, but they communicate as much with their gestures and steps as with their voices. The Chou (clown) is the only character permitted by tradition to speak in modern Beijing dialect or to improvise onstage.

Finally, a word about the trappings of the stage. Costumes are often elaborate, and they always reflect the social status of the character. Sleeves are especially

important, and are carefully managed by the actors for expressive purposes. Stage sets, however, tend to be minimal or non-existent. Audiences are expected to imagine the scene, which is brought to life through the use of symbolic props. A table, for example, might serve as a wall, a mountain, or a bed, while a single oar is enough to suggest the presence of a boat.

The Tale of the White Snake

We will see all of these elements at play in our example, Tian Han’s dramatization of The Tale of the White Snake. The source of this opera is a legend concerning a white snake spirit that transforms into a young woman named Bai Suzhen after consuming a substance that grants immortality and wisdom. The legend contains many episodes, but Tian chose to focus on events that lead up to and follow Bai’s marriage to Xu Xian, who through a twist of fate was originally responsible for her powers. Tian himself was a leading playwright in the first half of the 20th century, but he was condemned by Mao’s government in 1966 for writing a play that was considered to undermine Communist values. He died in prison two years later.

We will examine two scenes from The Tale of the White Snake, which, as a typical martial opera, contains both civil and martial scenes. The first, a civil scene, comes from near the beginning of the opera. Bai Suzhen and her friend Xiao Qing (also previously a snake) have been caught in a downpour when they meet Xu Xian.

The three of them share a boat, and Bai and Xu proceed to fall in love. This excerpt will allow us to hear a variety of speech and song types, to hear the orchestra in its various roles, and to witness the conventions by which actors communicate their emotions and conjure up absent settings and props.

The second scene, which is martial in character, concludes the initial episode of the couple’s romance. A few months after their marriage, Xu dies of fright after seeing his wife in her snake spirit form. Bai has journeyed to Mount Emei, home of the immortals, where she hopes to obtain a magical fungus that will bring Xu back to life. This scene contains almost no singing, but instead features acrobatics and martial arts as Bai battles the guardians of the sacred shrine.

Our first scene begins with the entrance of Xu Xian, who sings an aria to explain his recent activities, describe the weather, and clarify that he has no interest in love. He sings in a high, falsetto range, as is typical of Sheng-type characters. The orchestra both accompanies and doubles him, following the contour of his melody and arriving at the same final pitches. The orchestra, however, does not play only what he sings, but also tacks on repeated motifs that add rhythmic and melodic interest. Although the aria has a regular pulse for the most part, it slows at the end as the singer adds ornaments to draw out the final notes.

|

First excerpt from The Tale of the White Snake. Playwright: Tian Han. Performance: Chinese National Peking Opera Company |

Xu’s aria is followed by spoken dialogue between the characters, which is punctuated by percussive bursts. Soon, however, they are interrupted by singing from offstage. This aria, performed by a boatman, is quite different in character from Xu’s lively aria. It is slower and the notes more connected to one another—a style that would be described in the West as legato. Also, the boatman’s aria is accompanied by the dizi, a bamboo flute, in addition to the standard instruments. Finally, the heterophonic texture is more clear, since the orchestral instruments double the voice without adding any additional pitches.

Xu engages the boatman to take him and the two ladies to their destinations, and the boatman invites them to board. There is, of course, no boat. Instead, the actors help us to imagine it using carefully choreographed actions. After Bai and Xiao step into the boat, for example, they sway back and forth in perfect unison, as if being rocked by gentle waves. The journey of the boat is accompanied by appropriate music from the orchestra, to the melody of which the boatman sings a suitable Chinese proverb.

During the journey, all three characters engage in an extended accompanied musical number that combines singing and speaking. Again, the conclusion of the aria, sung by Bai, slows gradually to a stop as she makes the vital observation that Xu is a very nice young man. Pantomime and speech follow as the boat arrives at its first destination. The scene concludes with another musical sequence, in which Bai thanks Xu for his aid. Her final warning that he not break her heart is particularly effective: She draws the words out, singing unaccompanied for some time and concluding with a long series of ornaments. The phrase “gaze through autumn waters” is an idiom that indicates that one is waiting expectantly for another with tears in one’s eyes.

The scene ends with orchestral music to accompany Bai and Xiao’s departure from the stage. We now hear another instrument clearly: the sheng, or mouth organ. The sheng consists of a series of vertical reed pipes attached to a mouthpiece. The instrument is held with both hands, and the player positions their fingers over openings to sound the various pipes. The sheng will be heard during interludes such as this throughout the opera, although it seldom accompanies singing.

The scene we have just examined includes a typical mix of song, speech, and instrumental music, accompanied by symbolic movement and punctuated with percussive sound effects. As in European opera, speech (often cast as recitative in the Western tradition) moves the plot along, while song provides an opportunity for characters to express their emotions or reflect on what has happened.

Our next scene10 is quite different. Because this scene is martial in character, the focus is not on speech or song but on action. Bai sings to mark her entrance onto the stage, but she then executes an extended martial display to percussion accompaniment. Next she sings an excited aria about her mission to save her husband. When the guardian of the shrine blocks Bai’s way, she begs his mercy using speech. He refuses to assist her, and they enter into a long physical battle accompanied only by the percussion section. The battle features remarkable acrobatics from both of the guardians, who represent a Chou character type known as Wu Chou, or “military clown.”

|

Second excerpt from The Tale of the White Snake. Playwright: Tian Han. Performance: Chinese National Peking Opera Company |

Bai is ultimately defeated by the guardians, but the scene ends with an elder immortal gifting the magical fungus to Bai and sending her away to revive her husband. The two characters do not sing, but their dramatic and highly melodic speech is executed over orchestral accompaniment featuring both the dizi and sheng. After the long stretch of percussive music, the entrance of the full orchestra effectively underscores the emotion of the scene, communicating both the mercy of the immortal and the grateful joy of Bai.