4.2.3: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart - The Magic Flute

- Page ID

- 92112

During his lifetime, Monteverdi saw opera become mainstream popular entertainment in Venice. Over the next few centuries, opera became the most prominent form of public entertainment across all of Europe. Although the practice was first developed in Italian-speaking cities, it soon spread to France, England, and Germany, where new forms of opera were developed that catered to local tastes and languages. Italian opera remained so dominant, however, that it was performed—most often in its original language—in every European country. Opera was not truly dethroned as the West’s favorite form of entertainment until talking pictures became mainstream in the 1930s.

Although the variety and riches of the European opera tradition can reward a lifetime of study, we will examine only one more example here. This example was chosen for its historical significance, its intrinsic interest, and the many ways in which it contrasts with Orpheus. While Orpheus is a serious opera written for court performance in the early Baroque style, The Magic Flute (1791), composed nearly two hundred years later, is a comic opera created for commercial, public performance, and it exemplifies the pinnacle of the Classical style. It is also the work of the most important opera composer of the era: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791).

Mozart’s Career

Mozart was born into a musical family in the city of Salzburg. His father Leopold was a composer and violinist at the court of the Archbishop of Salzburg. Leopold was successful in his career, but he soon realized that his children possessed greater talent than he did. He subsequently abandoned composing to focus on their education. Mozart had an older sister, Marianne, who was his equal as a child prodigy. Both children mastered the harpsichord and fortepiano (a predecessor to the modern piano), while Mozart also became an expert violinist. Beginning in 1762, Leopold took his children on extensive tours to perform for heads of state across Europe. Marianne, however, was forced to abandon public performance when she became old enough to marry. Although there is some evidence that she composed music later in life, she was never given the opportunity to pursue a career.

Mozart, on the other hand, was expected to follow in the footsteps of his father, and upon the conclusion of his final tour in 1773 he took a job at the Salzburg court. Mozart, however, was dissatisfied with the provincial life he led. His exposure as a child to the great cities and courts of Europe had whetted his appetite for cosmopolitan excitement. He also wanted greater personal freedom, and resented being subservient to an employer. In 1781, he quarrelled with the Archbishop of Salzburg and was released from his position. Although his father was disappointed and concerned, Mozart was elated. He immediately moved to Vienna, an important center of politics and culture in the German- speaking world, and set out to build an independent career for himself.

In the late 18th century, there were few opportunities for a freelance musician to make a living. Most composers were employed by a court or church. Mozart, however, was able to capitalize on his fame as a child prodigy, and he had many marketable skills. He taught private piano lessons—although only to the elite young ladies of the city, and for a high fee. He wrote music for publication and accepted commissions. And he put on regular concerts of his music, each of which featured an appearance by the composer himself at the piano in the performance of a new concerto.

Finally, Mozart wrote operas in every genre of his day. He was fluent in various operatic styles and experienced in the conventions of the musical stage: Mozart, after all, had composed and premiered his first opera at the age of 13. In Vienna of the late 18th century, there were audiences for both Italian and German opera. Italian opera was divided into the old-fashioned opera seria (“serious opera”), which told heroic stories of gods and kings, and the newer opera buffa (“comic opera”), which portrayed characters from various social classes in humorous situations. The Magic Flute, however, is an example of a Singspiel (“sing-play”): a German-language comic opera with spoken dialogue and catchy songs. Of the three genres, Singspiel was the least respectable and sophisticated.

Mozart poured most of his energy into opera buffa. In collaboration with the court librettist Lorenzo da Ponte, he created three works—The Marriage of Figaro (1786), Don Giovanni (1787), and All Women Do It (Italian: Cosí fan tutte; 1790)—that have maintained a central place in the operatic repertoire ever since. Although all three of these operas contain comical characters and situations, each conveys a moral and is essentially serious in its purpose. The same is true of Mozart’s last opera, The Magic Flute (1791).

In the final years of his career, Mozart struggled to make a living. Despite early success, he found that his audiences had largely evaporated by 1787. This was due both to the vagaries of fashion and economic difficulties. Whatever the cause, he was no longer able to sell concert tickets, and was forced to abandon his rather lavish lifestyle. He and his wife moved to less expensive lodgings, gave up their carriage, and sold many of their belongings. At the time Mozart received the commission to write The Magic Flute, therefore, he was eager to increase his income. Although 1790 saw a general improvement in Mozart’s fortunes, he became ill while in Prague for the premiere of his final opera seria, The Clemency of Titus (1791), and died on December 5, just a few weeks after the premiere of The Magic Flute.

The Magic Flute

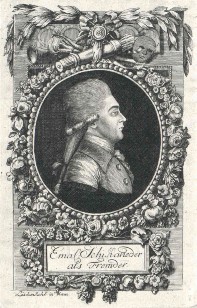

The Magic Flute was largely conceived by the man who commissioned Mozart’s participation in the project, Emanual Schikaneder. Schikaneder was the head of a theatrical troupe that performed at the Theater auf der Wieden, which was located in the Wieden district of Vienna. He and Mozart had known each other for many years, and Mozart had contributed music to several of his collaborative productions. Acting in his role as impresario, Schikanader had a hand in every step of the opera’s development: he came up with the idea of staging a series of fairy tale operas, wrote the libretto for The Magic Flute, assumed financial responsibility, acted as director, and played one of the leads. He is even reported to have made suggestions to Mozart that were incorporated into the score.

Although The Magic Flute can certainly be described as a fairy tale, it is a fairy tale with a political message. In particular, The Magic Flute embodies Enlightenment values, celebrating the triumph of reason over superstition and the moral equality of individuals from different social classes. It also contains multiple references to Freemasonry, which, in late-18th century Vienna, was committed to the furtherance of Enlightenment ideals. Both Mozart and Schikaneder were Freemasons. The Masonic elements include various symbols that featured in the original set design, references to the four elements (earth, air, water, and fire), fixation on the number three, and the tale’s setting in Egypt. Mozart also incorporated the rhythmic knock of the Masonic initiation ritual into his overture.

The plot, in a much simplified form, is as follows: The curtain rises on Prince Tamino fleeing from a serpent. Although he is rescued by three female attendants to the Queen of the Night, he awakens to find Papageno, a bird catcher, who takes credit for defeating the monster. When the women return, they chastise Papageno and show Tamino a portrait of Princess Pamina, the Queen’s daughter. He immediately falls in love with her, but is told that she has been kidnapped by the evil sorcerer Sarastro. The Queen herself appears to tell Tamino that he can marry her daughter if he rescues her. The Queen’s attendants give each of the men a magic instrument to help in their quest: a flute for Tamino and a set of bells for Papageno.

At the end of Act I, Tamino finds his way to Sarastro’s temple, but there he learns that the sorcerer is in fact benevolent, and that it is the Queen of the Night who has evil intentions. Sarastro had taken Pamina in order to protect her from her mother’s influence. Tamino and Pamina finally meet, and Pamina reciprocates his affection. Sarastro, however, refuses to permit the union before Tamino has completed a series of trials (based on Masonic ritual) to prove his spiritual worthiness.

Act II sees conflict between Pamina and her mother and suffering as Pamina awaits Tamino’s successful passage through the trials. The magic flute and bells each serve their respective holders as they seek personal fulfillment. In the end, the two lovers reject the evil influence of the Queen of the Night and join Sarastro’s enlightened brotherhood. And Papageno, who mourns his lonely existence, is rewarded for his faithfulness with a wife: Papagena.

The Magic Flute is rich with comedy, provided by Papageno (and, in a few scenes, the equally ridiculous Papagena), and the opera as a whole is highly entertaining. Most of the characters, however, are serious in purpose, and the story itself certainly carries a message.

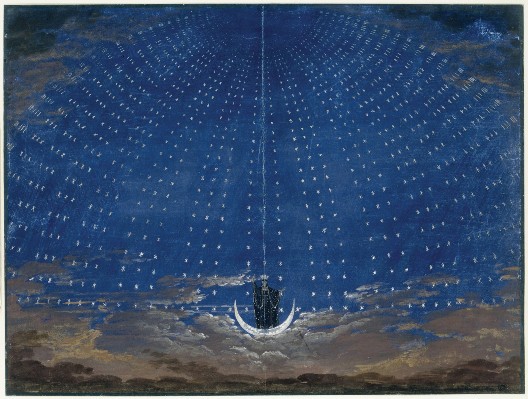

The Queen of the Night represents forces that seek to suppress knowledge and clarity in favor of fear, insularity, and irrationality. Some scholars have identified her with the Roman Catholic Empress Maria Theresa, and have interpreted the opera as an attack on Catholicism. This is contentious, however: On the one hand, the Catholic Church was opposed to Freemasonry, but on the other, Mozart himself was a devout Catholic. Whatever the specifics, the Queen of the Night certainly embodies anti-Enlightenment values. Sarastro, on the other hand, is the wise, generous, and benevolent head of state. He exemplifies the political principle of rule by an Enlightened monarch, which many at the time believed to be the ideal form of government. He grants agency and freedom to his subjects, but demands that they hold themselves to high intellectual and moral standards. In the end, the protagonists—Tamino and Pamina—choose modern, Enlightened thinking over the beguiling superstitions of the past.

The opera conveys other messages as well—not all of which are so palatable. Women are certainly not portrayed in a positive light. The realm governed by the evil Queen is entirely female, while the light-filled court of Sarastro is predominantly male. Although Pamina eventually joins Tamino in his trials, her role is to support him: The couple’s salvation relies primarily on his strength of character, and several musical numbers reinforce the idea that a wife must be subservient to her husband. The other female lead, Papagena, is literally a gift to a male character.

Likewise, the opera takes an ambivalent stance toward class distinctions. On the one hand, it portrays low-class characters in an essentially positive light. Papageno might be a buffoon, but he is on the side of good and capable of exhibiting strong moral character. This is an advance on previous operas, in which servants existed only to serve. At the same time, the low-class and high-class characters are kept at a distance from one another. Although Pamina and Papageno are friends and at one point sing a duet about the value of marriage, there is no question of them ending up together. A princess must marry a prince, while a bird catcher must marry within his own social class. Papageno is treated with the loving condescension that all members of his class supposedly deserve.

The Magic Flute, like many operas, also has a race problem. The synopsis above omitted the character of Monostatos, a black man who repeatedly threatens Pamina with sexual assault. Although he initially serves Sarastro as head of his slaves, he defects to the Queen’s side in hopes of winning Pamina for himself. And of course, the fact that Sarastro keeps slaves should also raise eyebrows.

The Magic Flute was a product of its time and place, but all of these issues must be addressed in modern stagings. One of the strengths of live theater is that scripts can be reinterpreted by directors and actors. The challenges of doing so, however, have not been trivial. Many operatic narratives promote social values that are no longer widely accepted. Many also portray non-Western characters or societies in demeaning ways. The inclusion of non-white characters also provides interpretive challenges. While the practice of blackface performance, in which a white actor uses make-up to portray a character of African descent, has been condemned as racist in almost all spheres for the past half century, it is still sometimes used on the opera stage.

Opera companies continue to perform The Magic Flute, however, because the music is delightful. (A clever director can address most of its messaging problems—for example, Monostatos does not have to be black.) The arias that Mozart produced for this opera are unusually diverse and entertaining. This was the case for several reasons. To begin with, he was writing for a commercial theater that attracted a middle-class audience. Most of his listeners were looking for a fun night out, not a transcendent artistic experience. In addition, not all of the actors in Schikanader’s troupe had equivalent musical capabilities. Some were highly-trained opera singers, but others—including Schikander himself, who played Papageno—could barely carry a tune. Mozart, therefore, carefully tailored his writing to each individual singer.

“I am a bird catcher”

With this in mind, we will examine four selections from The Magic Flute. We will begin with Papageno’s first number, “I am a bird catcher.”5 This is the aria that Papageno sings to introduce himself to Tamino. In it, he sings about his simple life, wandering the countryside in search of birds, and expresses his wish to be equally adept at capturing the hearts of young women. The music created by Mozart effectively communicates Papageno’s character, for he writes what is effectively a strophic folk song. It is in a cheerful major mode and contains only the simplest of harmonies, while the jaunty tempo establishes Papageno’s carefree attitude. We hear Papageno’s flute, which he uses to attract birds, in the second half of each of the two verses.

|

“I am a bird catcher” from The Magic Flute 5. Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Performance: Hermann Prey with the Staatskapelle Dresden, conducted by Otmar Suitner (1967) |

In addition to being dramatically appropriate, this music is also easy to sing. The orchestra begins by playing the entire melody, and the singer, upon entering, is doubled by the violins. Both of these features would have greatly helped Schikaneder give a successful performance. In addition, the vocal range is very small, spanning only a single octave, and positioned comfortably for an average male (not too high or low). Finally, the melody moves mostly by step, with few difficult leaps. Although the role of Papageno is always sung by a highly-trained professional in modern productions, his arias could easily be learned by almost anyone.

Other members of Schikaneder’s troupe were more skilled. In fact, the unusual capabilities of the actors who played the Queen of the Night and Sarastro inspired Mozart to write arias that continue to challenge modern singers. At the same time, the music sung by these two characters accurately reflects their respective roles in the drama.