3.4: Gustav Holst - The Planets

- Page ID

- 90687

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

While John Williams’s approach to creating the Star Wars soundtrack can be traced through Wagner, his music is more heavily influenced by other composers and works. The most frequently noted of these is the orchestral suite The Planets (1914-1916) by British composer Gustav Holst (1874- 1934). The reasons for which Williams chose to borrow from Holst are simple enough to understand. Holst was one of the first composers to write music about outer space, and he did so with a dramatic flair that has kept this work in the repertoire ever since its 1920 premiere.

Holst and The Planets

Holst studied composition at the Royal College of Music in London, where he met with moderate success. He was not attracted to the life of a professional musician (Holst played the trombone), but he struggled to make a living as a composer. In 1903, therefore, Holst began teaching music in schools. Although he would write some of his most successful music for the orchestras he directed, he had little time in which to pursue his craft. Nevertheless, Holst continued to produce serious concert pieces and his reputation steadily grew.

Holst finally earned national attention in 1920, first with a work for choir and orchestra entitled The Hymn of Jesus and then with The Planets. The Hymn of Jesus paved the way for The Planets’ success by establishing for Holst a reputation as a mystic and spiritual composer. As we will see, these qualities are prominent in the orchestral suite. Although the entire suite was not premiered until 1920, Holst had been at work on it since 1913. He first wrote the music for two pianos, and produced the orchestral score only after the composition was complete.

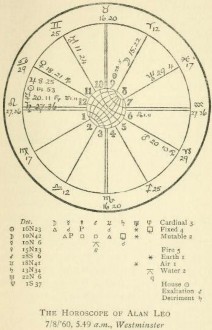

Much of Holst’s work as a composer can be traced to his personal interests. This is certainly true of The Planets. In 1913, Holst travelled to Majorca with a group of fellow artists, who introduced him to the study of astrology. Holst became fascinated and immersed himself in the work of British astrologist Alan Leo, reading his book What Is a Horoscope and How Is It Cast?. The idea of composing an orchestral suite came to him almost immediately, and he began sketching the first movement, “Mars,” that same year.

Holst’s intent was to capture the astrological significance of each of the planets, as described by Leo. He was interested in the specific characteristics bestowed on those who were born under the influence of each individual planet. At the same time, Holst was a composer first and an astrologer second. His primary concern was musical cohesion and expression. As a result, he frequently deviated from Leo’s prescription, and in the end used Leo’s writings merely as an inspiration for his own creative work.

It seems that Holst was worried that audiences would not take his music seriously. An orchestral work inspired by celestial bodies, after all, might easily be dismissed as a mere novelty, especially when compared to the traditional symphonies that formed the core of the concert hall repertoire (see Chapter 7). For this reason, Holst first titled his suite Seven Pieces for Orchestra, only later changing it to The Planets. He added the individual movement names, indicating which planet the music is about, only just before the work was published. The descriptive titles qualify The Planets as program music, a term used to identify an instrumental composition that tells a story or paints a picture. Holst chose not to order the movements in order of their distance from the sun, instead swapping Mars and Mercury. The reason for this decision is clear enough: The music that Holst composed to depict Mars makes a great opener for the work.

The Planets was a massive success. It was immediately programmed by orchestras all over England and has since become one of the most familiar and most frequently performed pieces in the orchestral repertoire. All the same, Holst came to regret his biggest hit. He continued to develop and grow as a composer, and within just a few years he considered The Planets to be outdated. Critics, on the other hand, were disappointed when Holst’s new compositions did not sound like his original blockbuster. Although Holst went on to write many beloved works, he never matched the success of The Planets.

We will examine the first and last movements of Holst’s suite: “Mars, the Bringer of War” and “Neptune, the Mystic.” “Mars” served as a model for John Williams’s “Imperial March” in the Star Wars soundtrack, while “Neptune” seems to have had a general influence on Williams’s musical portrayals of space.

Mars12

In astrological terms, the planet Mars is associated with confidence, self assertion, aggression, energy, strength, ambition, and impulsiveness. Leo described those born under the influence of Mars as “fond of liberty, freedom, and independence,” noting that they “may be relied upon for courage” and are “fond of adventure and progress” but are also “headstrong and at times too forceful.” In mythological terms, Mars is the ancient Roman god of war.

|

“Mars” from The Planets 12. Composer: Gustav Holst Performance: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, conducted by James Levine (1990) |

Holst seems to have combined these influences in his music, which is overtly militaristic. The staccato rhythms heard at the beginning are the rhythms of a military march. At first they are played by the entire string section using a special technique, known as col legno, for which players turn their bows upside down and bounce the wooden stick on the string. Later, the snare drum—an actual military instrument—plays the same rhythm, which is heard almost throughout the movement. There is something very strange about Holst’s march, however: It is in quintuple meter, with five beats per measure. It would be very difficult to actually march to this music.

Holst uses other strategies as well to communicate the character of Mars. The first melody we hear is low and ominous, consisting only of a rising gesture followed by a small descent. As the texture thickens, the volume increases and the melodic gestures seems more threatening. The introduction of trumpets and other brass instruments reinforces the militaristic flavor of the movement. In the middle section, the trumpets seem to be sounding battle calls. Finally, the whole movement comes to a crashing close with the strings and brass playing as loudly and violently as possible.

Neptune13

Holst’s representation of Neptune, the final planet in his suite, is entirely different. This is natural enough, given Holst’s astrological mindset, for the influence of Neptune is associated with idealism, dreams, dissolution, artistry, empathy, illusion, and vagueness. Holst creates music, therefore, that captures these same qualities.

|

“Neptune” from The Planets 13. Composer: Gustav Holst Performance: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, conducted by James Levine (1990) |

We might begin with a discussion of timbre. “Neptune” includes a sound that is completely absent from the other movements: women’s voices. Holst includes two choirs of sopranos and altos, making for six separate vocal parts. The women don’t sing words, however, but are instead instructed to sustain long, open “ah” vowels. The singers therefore function in the same way as instruments, bringing an ethereal, transparent quality to the upper register of the orchestra.

Apart from the voices, “Neptune” calls for the same instruments as “Mars.” However, Holst deploys these instruments quite differently. He hardly uses the brass section at all, relegating them to low, sustained pitches in the background of the texture. Holst assigns the melody to wind instruments, with a preference for the airy sound of the flutes and the reedy timbre of the oboe and English horn. He also foregrounds the two harps and a percussion instrument called the celeste, which has a keyboard similar to that of a piano but produces the sound of bells.

The articulation in “Neptune” is completely unlike that heard in “Mars.” While “Mars” is characterized by abrupt, accented rhythms, the pitches in “Neptune” are sustained and connected. Interestingly, this is the only movement that Holst originally composed for organ instead of piano. He felt that the organ, which can sustain pitches indefinitely, was better able to capture his musical vision. While both “Mars” and “Neptune” are in quintuple meter, the differences in articulation and tempo (“Neptune” is much slower) means that the two movements have completely different effects on the listener.

Finally, we might say something about the melody and harmony. There are no catchy tunes in “Neptune.” Instead, the wind instruments and voices repeat floaty, circular melodies that don’t seem to go anywhere. “Neptune” is also not in any particular key. Instead, the music rocks back and forth between seemingly unrelated harmonies. All of this creates the sensation of being unmoored. It is hard to predict where the music is going, but easy to enjoy the beautiful sounds.