1.10: George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824)

- Page ID

- 41766

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Romantic emphasis on the individual was double-edged. Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner travels through a landscape of his mind and spirit, a solitary individual closed off from the guidance and support of others—until he surpasses himself through an act of love. And while the Mariner learns to appreciate the happiness derived from the company of others, including all of nature (and the supernatural), his unconscious act of self-assertion in killing the albatross also effected a breaking out of boundaries, an expansion of our knowledge of human nature.

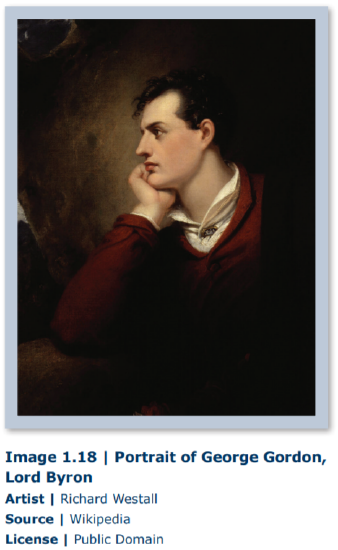

This sense of the power and danger of self-realization actuates the Byronic Hero, a Romantic figure named after the poet George Gordon, Lord Byron. A solitary figure, an exile and desperate wanderer at home neither with himself nor others, the Byronic Hero rebelled like Satan against a God he resembled, and like Satan his own mind made his own heaven and hell. His innate sense of superiority and his charisma epitomized both his strengths and limitations. His doubleness, like that of John Milton’s Satan in Paradise Lost—of glory subdued, of being piteous and unpitied, marked and protected—paralleled the doubleness in Byron’s life and works.

Born into an aristocratic family, George Gordon functioned with a clubbed right foot, a disability that many of his contemporaries considered a flaw and that later contributed to characteristics of the flawed Byronic Hero. His father Captain John “Mad Jack” Byron was a spendthrift who recovered his fortune by marrying heiresses. He and his first wife, Amelia Osborne, Machioness of Camarthan, had a daughter, Augusta Maria Byron. Amelia died in 1784; Captain Byron married his second wife, Catherine Gordon, in 1785, before he died in 1791.

Born into an aristocratic family, George Gordon functioned with a clubbed right foot, a disability that many of his contemporaries considered a flaw and that later contributed to characteristics of the flawed Byronic Hero. His father Captain John “Mad Jack” Byron was a spendthrift who recovered his fortune by marrying heiresses. He and his first wife, Amelia Osborne, Machioness of Camarthan, had a daughter, Augusta Maria Byron. Amelia died in 1784; Captain Byron married his second wife, Catherine Gordon, in 1785, before he died in 1791.

Byron inherited his title while still in grammar-school. He became the sixth Baron Byron of Rochdale with a family seat in Nottinghamshire, Newstead Abbey. Lord Byron studied at Harrow and at Trinity College, Cambridge, then took the Grand Tour to obtain knowledge of the world. After visiting Portugal, Albania, Spain, Italy, and Greece, Byron returned to England and entered public life. He sat in the House of Lords on the side of the liberals. His first speech in Lords denounced a proposal for the death penalty for weavers who rioted and protested industrialism by breaking machines.

In 1812, he published the first two cantos of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. It became a sensation, and Byron “woke up and found himself famous.” He claimed Harold was a fiction, but readers conflated hero and author in this first appearance of the Byronic hero. A series of ensuing “Eastern” tales added to Byron’s exotic aura. The Corsair (1814) sold 10,000 copies on its release; Hebrew Melodies (1815) contains Byron’s most famous lyrics, including “She Walks in Beauty.” The collection also expresses anti-imperialism and the desire for the freedom of nations subject to empires like the Ottoman or Austrian.

Drawn into the social life of the London aristocrat, Byron met and had an affair with Lady Caroline Lamb, who famously described Byron in her diary as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” Their affair ended badly, and Lady Caroline avenged herself by publishing Glenarvon (1816), a thinly-veiled roman à clef depicting a Byron-like hero who seduced women and died ignominiously.

Friends encouraged Byron to recover his tarnished reputation by marrying Henriette Milbanke who agreed to marry Byron in order to redeem him. The unhappiness of their marriage was perhaps exacerbated by Byron’s growing intimacy with his half-sister Augusta. Byron was thought to be the father of Augusta’s daughter Medora. After the birth of their daughter Ada Augusta, Henriette Millbanke divorced Byron; in order to do so, she had to prove just cause, and the complaints she brought against Byron, including incest and sodomy, caused such a scandal that Byron declared that “everybody and her husband hates me.” He left England never to return.

He subsequently traveled throughout Europe, befriended Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, fathered a daughter named Allegra with Mary Shelley’s half-sister Claire Clairmont (1798-1879), and became the cavaliere servante of Theresa Guccioli who was involved in the movement to liberate Italy from Austrian rule and who ultimately encouraged Byron’s interest in Greek Independence from Turkey.

His final political activity of financially supporting Greek independence made his reputation as an upholder of freedom and individual liberty at all costs, especially as he believed Greece to be the seat of democracy and his spiritual home. He died there of fever after the Battle of Missolonghi. Greece today still celebrates Byron as a national hero.

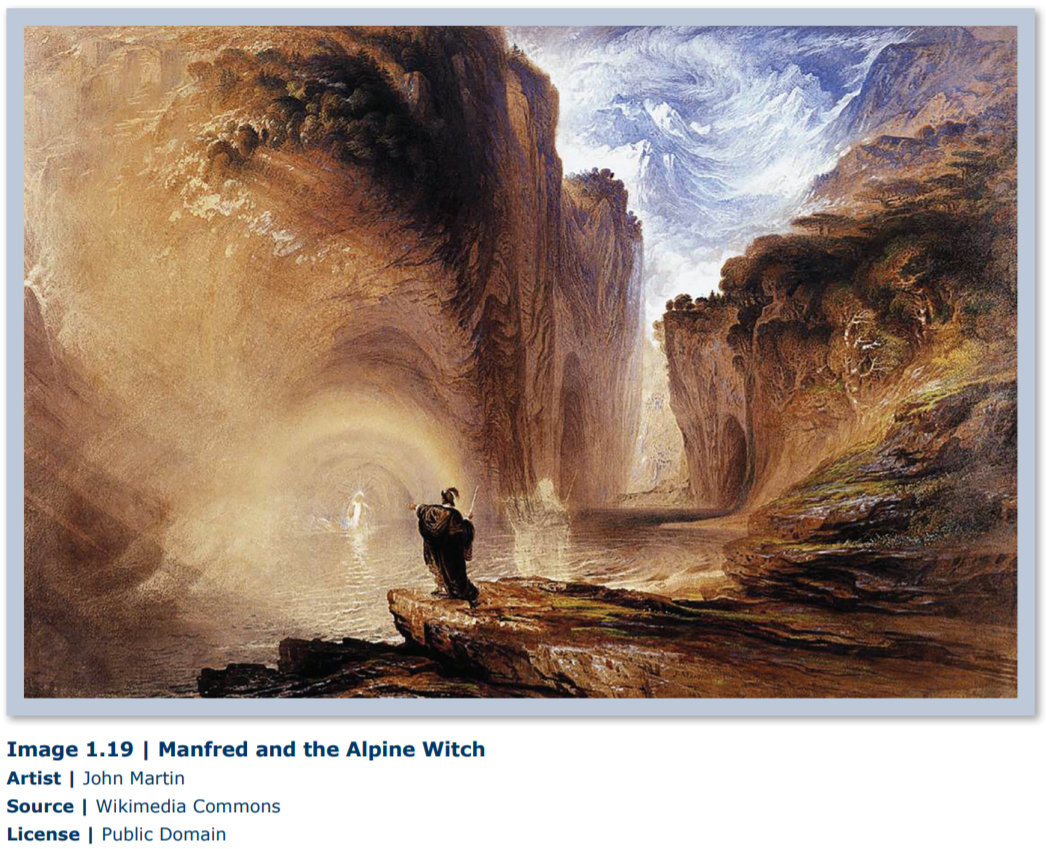

The most characteristic feature of Byron’s writing is its autobiographical quality. He seemed to live his life as though it were a work of art. As in his life, his poetry blended “virtue” with “vice.” For example, the so-called sin that drives Manfred’s beloved Astarte to commit suicide recalls Byron’s own relationship with his half-sister Augusta. Manfred’s extreme skepticism, his sense that he is his own master embodies qualities of both Byron himself and his eponymous hero. In almost all of his writing, Byron’s strength of expression is clear, a strength which he himself likened to the spring of a tiger.

1.10.1: Manfred, A Dramatic Poem

‘There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.’

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

MANFRED

CHAMOIS HUNTER

ABBOT OF ST. MAURICE

MANUEL

HERMAN

WITCH OF THE ALPS

ARIMANES

NEMESIS

THE DESTINIES

SPIRITS, etc

The scene of the Drama is amongst the Higher Alps—partly in the Castle of Manfred, and partly in the Mountains.

Act I

SCENE I

MANFRED alone.—Scene, a Gothic Gallery.—Time, Midnight.

MANFRED. The lamp must be replenish’d, but even then

It will not burn so long as I must watch.

My slumbers—if I slumber—are not sleep,

But a continuance of enduring thought,

Which then I can resist not: in my heart

There is a vigil, and these eyes but close

To look within; and yet I live, and bear

The aspect and the form of breathing men.

But grief should be the instructor of the wise;

Sorrow is knowledge: they who know the most 10

Must mourn the deepest o’er the fatal truth,

The Tree of Knowledge is not that of Life.

Philosophy and science, and the springs

Of wonder, and the wisdom of the world,

I have essay’d, and in my mind there is

A power to make these subject to itself—

But they avail not: I have done men good,

And I have met with good even among men—

But this avail’d not: I have had my foes,

And none have baffled, many fallen before me— 20

But this avail’d not: Good, or evil, life,

Powers, passions, all I see in other beings,

Have been to me as rain unto the sands,

Since that all-nameless hour. I have no dread,

And feel the curse to have no natural fear

Nor fluttering throb, that beats with hopes or wishes

Or lurking love of something on the earth.

Now to my task.—

Mysterious Agency!

Ye spirits of the unbounded Universe,

Whom I have sought in darkness and in light! 30

Ye, who do compass earth about, and dwell

In subtler essence! ye, to whom the tops

Of mountains inaccessible are haunts,

And earth’s and ocean’s caves familiar things—

I call upon ye by the written charm

Which gives me power upon you—Rise! appear! [A pause.]

They come not yet.—Now by the voice of him

Who is the first among you; by this sign,

Which makes you tremble; by the claims of him

Who is undying,—Rise! appear!—Appear! [A pause.] 40

If it be so.—Spirits of earth and air,

Ye shall not thus elude me: by a power,

Deeper than all yet urged, a tyrant-spell,

Which had its birthplace in a star condemn’d,

The burning wreck of a demolish’d world,

A wandering hell in the eternal space;

By the strong curse which is upon my soul,

The thought which is within me and around me,

I do compel ye to my will. Appear!

[A star is seen at the darker end of the gallery: it is

stationary; and a voice is heard singing.]

FIRST SPIRIT.

Mortal! to thy bidding bow’d, 50

From my mansion in the cloud,

Which the breath of twilight builds,

And the summer’s sunset gilds

With the azure and vermilion

Which is mix’d for my pavilion;

Though thy quest may be forbidden,

On a star-beam I have ridden,

To thine adjuration bow’d;

Mortal—be thy wish avow’d!

Voice of the SECOND SPIRIT.

Mont Blanc is the monarch of mountains; 60

They crown’d him long ago

On a throne of rocks, in a robe of clouds,

With a diadem of snow.

Around his waist are forests braced,

The Avalanche in his hand;

But ere it fall, that thundering ball

Must pause for my command.

The Glacier’s cold and restless mass

Moves onward day by day;

But I am he who bids it pass, 70

Or with its ice delay.

I am the spirit of the place,

Could make the mountain bow

And quiver to his cavern’d base—

And what with me wouldst Thou?

Voice of the THIRD SPIRIT.

In the blue depth of the waters,

Where the wave hath no strife,

Where the wind is a stranger

And the sea-snake hath life,

Where the Mermaid is decking 80

Her green hair with shells;

Like the storm on the surface

Came the sound of thy spells;

O’er my calm Hall of Coral

The deep echo roll’d—

To the Spirit of Ocean

Thy wishes unfold!

FOURTH SPIRIT.

Where the slumbering earthquake

Lies pillow’d on fire,

And the lakes of bitumen 90

Rise boilingly higher;

Where the roots of the Andes

Strike deep in the earth,

As their summits to heaven

Shoot soaringly forth;

I have quitted my birthplace,

Thy bidding to bide—

Thy spell hath subdued me,

Thy will be my guide!

FIFTH SPIRIT.

I am the Rider of the wind, 100

The Stirrer of the storm;

The hurricane I left behind

Is yet with lightning warm;

To speed to thee, o’er shore and sea

I swept upon the blast:

The fleet I met sail’d well, and yet

‘T will sink ere night be past.

SIXTH SPIRIT.

My dwelling is the shadow of the night,

Why doth thy magic torture me with light?

SEVENTH SPIRIT

The star which rules thy destiny 110

Was ruled, ere earth began, by me:

It was a world as fresh and fair

As e’er revolved round sun in air;

Its course was free and regular,

Space bosom’d not a lovelier star.

The hour arrived—and it became

A wandering mass of shapeless flame,

A pathless comet, and a curse,

The menace of the universe;

Still rolling on with innate force, 120

Without a sphere, without a course,

A bright deformity on high,

The monster of the upper sky!

And thou! beneath its influence born—

Thou worm! whom I obey and scorn—

Forced by a power (which is not thine,

And lent thee but to make thee mine)

For this brief moment to descend,

Where these weak spirits round thee bend

And parley with a thing like thee— 130

What wouldst thou, Child of Clay! with me?

The SEVEN SPIRITS

Earth, ocean, air, night, mountains, winds, thy star,

Are at thy beck and bidding, Child of Clay!

Before thee at thy quest their spirits are—

What wouldst thou with us, son of mortals—say?

MANFRED. Forgetfulness—

FIRST SPIRIT. Of what—of whom—and why?

MANFRED. Of that which is within me; read it there—

Ye know it, and I cannot utter it.

SPIRIT. We can but give thee that which we possess:

Ask of us subjects, sovereignty, the power 140

O’er earth, the whole, or portion, or a sign

Which shall control the elements, whereof

We are the dominators,—each and all,

These shall be thine.

MANFRED. Oblivion, self-oblivion—

Can ye not wring from out the hidden realms

Ye offer so profusely what I ask?

SPIRIT. It is not in our essence, in our skill; But—thou mayst die.

MANFRED. Will death bestow it on me?

SPIRIT. We are immortal, and do not forget;

We are eternal; and to us the past 150

Is, as the future, present. Art thou answered?

MANFRED. Ye mock me—but the power which brought ye here

Hath made you mine. Slaves, scoff not at my will!

The mind, the spirit, the Promethean spark, T

he lightning of my being, is as bright,

Pervading, and far-darting as your own,

And shall not yield to yours, though coop’d in clay!

Answer, or I will teach you what I am.

SPIRIT. We answer as we answer’d; our reply

Is even in thine own words.

MANFRED. Why say ye so? 160

SPIRIT. If, as thou say’st, thine essence be as ours,

We have replied in telling thee, the thing

Mortals call death hath nought to do with us.

MANFRED. I then have call’d ye from your realms in vain;

Ye cannot, or ye will not, aid me.

SPIRIT. Say; What we possess we offer; it is thine:

Bethink ere thou dismiss us, ask again—

Kingdom, and sway, and strength, and length of days—

MANFRED. Accursèd! what have I to do with days?

They are too long already.—Hence—begone! 170

SPIRIT. Yet pause: being here, our will would do thee service;

Bethink thee, is there then no other gift

Which we can make not worthless in thine eyes?

MANFRED. No, none: yet stay—one moment, ere we part—

I would behold ye face to face. I hear

Your voices, sweet and melancholy sounds,

As music on the waters; and I see

The steady aspect of a clear large star;

But nothing more. Approach me as ye are,

Or one, or all, in your accustom’d forms. 180

SPIRIT. We have no forms, beyond the elements

Of which we are the mind and principle:

But choose a form—in that we will appear.

MANFRED. I have no choice, there is no form on earth

Hideous or beautiful to me. Let him,

Who is most powerful of ye, take such aspect

As unto him may seem most fitting.—Come!

Seventh spirit (appearing in the shape of a beautiful female figure). Behold!

MANFRED. Oh God! if it be thus, and thou

Art not a madness and a mockery

I yet might be most happy—I will clasp thee, 190

And we again will be— [The figure vanishes.]

My heart is crushed!

[MANFRED falls senseless.]

(A voice is heard in the Incantation which follows.)

When the moon is on the wave,

And the glow-worm in the grass,

And the meteor on the grave,

And the wisp on the morass;

When the falling stars are shooting,

And the answer’d owls are hooting,

And the silent leaves are still

In the shadow of the hill,

Shall my soul be upon thine, 200

With a power and with a sign.

Though thy slumber may be deep,

Yet thy spirit shall not sleep;

There are shades which will not vanish,

There are thoughts thou canst not banish;

By a power to thee unknown,

Thou canst never be alone;

Thou art wrapt as with a shroud,

Thou art gather’d in a cloud;

And forever shalt thou dwell 210

In the spirit of this spell.

Though thou seest me not pass by,

Thou shalt feel me with thine eye

As a thing that, though unseen,

Must be near thee, and hath been;

And when in that secret dread

Thou hast turn’d around thy head,

Thou shalt marvel I am not

As thy shadow on the spot,

And the power which thou dost feel 220

Shall be what thou must conceal.

And a magic voice and verse

Hath baptized thee with a curse;

And a spirit of the air

Hath begirt thee with a snare;

In the wind there is a voice

Shall forbid thee to rejoice;

And to thee shall Night deny

All the quiet of her sky;

And the day shall have a sun, 230

Which shall make thee wish it done.

From thy false tears I did distil

An essence which hath strength to kill;

From thy own heart I then did wring

The black blood in its blackest spring;

From thy own smile I snatch’d the snake,

For there it coil’d as in a brake;

From thy own lip I drew the charm

Which gave all these their chiefest harm;

In proving every poison known, 240

I found the strongest was thine own.

By thy cold breast and serpent smile,

By thy unfathom’d gulfs of guile,

By that most seeming virtuous eye,

By thy shut soul’s hypocrisy;

By the perfection of thine art

Which pass’d for human thine own heart;

By thy delight in others’ pain,

And by thy brotherhood of Cain,

I call upon thee! and compel 250

Thyself to be thy proper Hell!

And on thy head I pour the vial

Which doth devote thee to this trial;

Nor to slumber, nor to die,

Shall be in thy destiny;

Though thy death shall still seem near

To thy wish, but as a fear;

Lo! the spell now works around thee,

And the clankless chain hath bound thee;

O’er thy heart and brain together 260

Hath the word been pass’d—now wither!

SCENE II

The Mountain of the Jungfrau.—Time, Morning.—

MANFRED alone upon the Cliffs.

MANFRED. The spirits I have raised abandon me,

The spells which I have studied baffled me,

The remedy I reck’d of tortured me;

I lean no more on super-human aid,

It hath no power upon the past, and for

The future, till the past be gulf’d in darkness,

It is not of my search.—My mother Earth!

And thou fresh breaking Day, and you, ye Mountains,

Why are ye beautiful? I cannot love ye. 270

And thou, the bright eye of the universe

That openest over all, and unto all

Art a delight—thou shin’st not on my heart.

And you, ye crags, upon whose extreme edge

I stand, and on the torrent’s brink beneath

Behold the tall pines dwindled as to shrubs

In dizziness of distance; when a leap,

A stir, a motion, even a breath, would bring

My breast upon its rocky bosom’s bed

To rest forever—wherefore do I pause? 280

I feel the impulse—yet I do not plunge;

I see the peril—yet do not recede;

And my brain reels—and yet my foot is firm.

There is a power upon me which withholds,

And makes it my fatality to live;

If it be life to wear within myself

This barrenness of spirit, and to be

My own soul’s sepulchre, for I have ceased

To justify my deeds unto myself —

The last infirmity of evil. Ay, 290

Thou winged and cloud-cleaving minister, [An eagle passes.]

Whose happy flight is highest into heaven,

Well may’st thou swoop so near me—I should be

Thy prey, and gorge thine eaglets; thou art gone

Where the eye cannot follow thee; but thine

Yet pierces downward, onward, or above,

With a pervading vision.—Beautiful!

How beautiful is all this visible world!

How glorious in its action and itself!

But we, who name ourselves its sovereigns, we, 300

Half dust, half deity, alike unfit

To sink or soar, with our mix’d essence make

A conflict of its elements, and breathe

The breath of degradation and of pride,

Contending with low wants and lofty will,

Till our mortality predominates,

And men are what they name not to themselves,

And trust not to each other. Hark! the note,

[The Shepherd’s pipe in the distance is heard.]

The natural music of the mountain reed

(For here the patriarchal days are not 310

A pastoral fable) pipes in the liberal air,

Mix’d with the sweet bells of the sauntering herd;

My soul would drink those echoes.—Oh, that I were

The viewless spirit of a lovely sound,

A living voice, a breathing harmony,

A bodiless enjoyment—born and dying

With the blessed tone which made me!

Enter from below a CHAMOIS HUNTER.

CHAMOIS HUNTER. Even so

This way the chamois leapt: her nimble feet

Have baffled me; my gains to-day will scarce

Repay my break-neck travail.—What is here? 320

Who seems not of my trade, and yet hath reach’d

A height which none even of our mountaineers

Save our best hunters, may attain: his garb

Is goodly, his mien manly, and his air

Proud as a freeborn peasant’s, at this distance—

I will approach him nearer.

MANFRED (not perceiving the other). To be thus—

Gray—hair’d with anguish, like these blasted pines,

Wrecks of a single winter, barkless, branchless,

A blighted trunk upon a cursèd root

Which but supplies a feeling to decay— 330

And to be thus, eternally but thus,

Having been otherwise! Now furrowed o’er

With wrinkles, plough’d by moments, not by years

And hours—all tortured into ages—hours

Which I outlive!—Ye toppling crags of ice!

Ye avalanches, whom a breath draws down

In mountainous o’erwhelming, come and crush me!

I hear ye momently above, beneath,

Crash with a frequent conflict, but ye pass,

And only fall on things that still would live; 340

On the young flourishing forest, or the hut And hamlet of the harmless villager.

CHAMOIS HUNTER. The mists begin to rise from up the valley;

I’ll warn him to descend, or he may chance

To lose at once his way and life together.

MANFRED. The mists boil up around the glaciers; clouds

Rise curling fast beneath me, white and sulphury,

Like foam from the roused ocean of deep Hell,

Whose every wave breaks on a living shore

Heap’d with the damn’d like pebbles.—I am giddy. 350

CHAMOIS HUNTER. I must approach him cautiously; if near

A sudden step will startle him, and he

Seems tottering already.

MANFRED. Mountains have fallen,

Leaving a gap in the clouds, and with the shock

Rocking their Alpine brethren; filling up

The ripe green valleys with destruction’s splinters;

Damming the rivers with a sudden dash,

Which crush’d the waters into mist, and made

Their fountains find another channel—thus,

Thus, in its old age, did Mount Rosenberg— 360

Why stood I not beneath it?

CHAMOIS HUNTER. Friend! have a care,

Your next step may be fatal!—for the love

Of him who made you, stand not on that brink!

MANFRED. (not hearing him). Such would have been for me a fitting tomb;

My bones had then been quiet in their depth;

They had not then been strewn upon the rocks

For the wind’s pastime—as thus—thus they shall be—

In this one plunge.—Farewell, ye opening heavens!

Look not upon me thus reproachfully—

Ye were not meant for me—Earth! take these atoms! 370

[As MANFRED is in act to spring from the cliff, the CHAMOIS HUNTER seizes and retains him with a sudden grasp.]

CHAMOIS HUNTER. Hold, madman!—though aweary of thy life,

Stain not our pure vales with thy guilty blood!

Away with me—I will not quit my hold.

MANFRED. I am most sick at heart—nay, grasp me not—

I am all feebleness—the mountains whirl

Spinning around me—I grow blind—What art thou?

CHAMOIS HUNTER. I’ll answer that anon.—Away with me!

The clouds grow thicker—there—now lean on me—

Place your foot here—here, take this staff, and cling

A moment to that shrub—now give me your hand, 380

And hold fast by my girdle—softly—well—

The Chalet will be gain’d within an hour.

Come on, we’ll quickly find a surer footing,

And something like a pathway, which the torrent

Hath wash’d since winter.—Come, ‘tis bravely done;

You should have been a hunter.— Follow me.

[As they descend the rocks with difficulty, the scene closes.]

Act II

SCENE I

A Cottage amongst the Bernese Alps.

MANFRED and the CHAMOIS HUNTER.

CHAMOIS HUNTER. No, no, yet pause, thou must not yet go forth:

Thy mind and body are alike unfit

To trust each other, for some hours, at least;

When thou art better, I will be thy guide—

But whither?

MANFRED. It imports not; I do know

My route full well, and need no further guidance.

CHAMOIS HUNTER. Thy garb and gait bespeak thee of high lineage—

One of the many chiefs, whose castled crags

Look o’er the lower valleys—which of these

May call thee Lord? I only know their portals; 10

My way of life leads me but rarely down

To bask by the huge hearths of those old halls,

Carousing with the vassals, but the paths,

Which step from out our mountains to their doors,

I know from childhood—which of these is thine?

MANFRED. No matter.

CHAMOIS HUNTER. Well, sir, pardon me the question,

And be of better cheer. Come, taste my wine;

‘Tis of an ancient vintage; many a day

‘T has thaw’d my veins among our glaciers, now

Let it do thus for thine. Come, pledge me fairly. 20

MANFRED. Away, away! there’s blood upon the brim!

Will it then never—never sink in the earth?

CHAMOIS HUNTER. What dost thou mean? thy senses wander from thee.

MANFRED. I say ‘t is blood—my blood! the pure warm stream

Which ran in the veins of my fathers, and in ours

When we were in our youth, and had one heart

And loved each other as we should not love,

And this was shed: but still it rises up

Colouring the clouds, that shut me out from heaven

Where thou art not—and I shall never be. 30

CHAMOIS HUNTER. Man of strange words, and some half-maddening sin

Which makes thee people vacancy, whate’er

Thy dread and sufferance be, there’s comfort yet—

The aid of holy men, and heavenly patience—

MANFRED. Patience and patience! Hence—that word was made

For brutes of burthen, not for birds of prey;

Preach it to mortals of a dust like thine,—

I am not of thine order.

CHAMOIS HUNTER. Thanks to heaven!

I would not be of thine for the free fame

Of William Tell; but whatsoe’er thine ill, 40

It must be borne, and these wild starts are useless.

MANFRED. Do I not bear it?—Look on me—I live.

CHAMOIS HUNTER. This is convulsion, and no healthful life.

MANFRED. I tell thee, man! I have lived many years,

Many long years, but they are nothing now

To those which I must number: ages—ages—

Space and eternity—and consciousness,

With the fierce thirst of death—and still unslaked!

CHAMOIS HUNTER. Why, on thy brow the seal of middle age

Hath scarce been set; I am thine elder far. 50

MANFRED. Think’st thou existence doth depend on time?

It doth; but actions are our epochs: mine

Have made my days and nights imperishable

Endless, and all alike, as sands on the shore

Innumerable atoms; and one desart

Barren and cold, on which the wild waves break,

But nothing rests, save carcases and wrecks,

Rocks, and the salt-surf weeds of bitterness.

CHAMOIS HUNTER. Alas! he’s mad—but yet I must not leave him.

MANFRED. I would I were—for then the things I see 60

Would be but a distemper’d dream.

CHAMOIS HUNTER. What is it

That thou dost see, or think thou look’st upon?

MANFRED. Myself, and thee—a peasant of the Alps—

Thy humble virtues, hospitable home

And spirit patient, pious, proud and free;

Thy self-respect, grafted on innocent thoughts;

Thy days of health, and nights of sleep; thy toils

By danger dignified, yet guiltless; hopes

Of cheerful old age and a quiet grave,

With cross and garland over its green turf, 70

And thy grandchildren’s love for epitaph;

This do I see—and then I look within—

It matters not—my soul was scorch’d already!

CHAMOIS HUNTER. And would’st thou then exchange thy lot for mine?

MANFRED. No, friend! I would not wrong thee, nor exchange

My lot with living being: I can bear—

However wretchedly, ‘t is still to bear—

In life what others could not brook to dream,

But perish in their slumber.

CHAMOIS HUNTER. And with this—

This cautious feeling for another’s pain, 80

Canst thou be black with evil?—say not so.

Can one of gentle thoughts have wreak’d revenge

Upon his enemies?

MANFRED. Oh! no, no, no!

My injuries came down on those who loved me—

On those whom I best loved: I never quell’d

An enemy, save in my just defence—

But my embrace was fatal.

CHAMOIS HUNTER. Heaven give thee rest!

And penitence restore thee to thyself;

My prayers shall be for thee.

MANFRED. I need them not,

But can endure thy pity. I depart— 90

‘T is time—farewell!—Here’s gold, and thanks for thee;

No words—it is thy due.

Follow me not; I know my path—the mountain peril’s past:

And once again, I charge thee, follow not! [Exit MANFRED.]

SCENE II

A lower Valley in the Alps.—A Cataract.

Enter MANFRED.

It is not noon—the sunbow’s rays still arch

The torrent with the many hues of heaven,

And roll the sheeted silver’s waving column

O’er the crag’s headlong perpendicular,

And fling its lines of foaming height along,

And to and fro, like the pale courser’s tall, 100

The Giant steed, to be bestrode by Death,

As told in the Apocalypse. No eyes

But mine now drink this sight of loveliness;

I should be sole in this sweet solitude,

And with the Spirit of the place divide

The homage of these waters.—I will call her.

[MANFRED takes some of the water into the palm of his hand, and flings it in the air, muttering the adjuration. After a pause, the WITCH OF THE ALPS rises beneath the arch of the sunbow of the torrent.]

Beautiful Spirit! with thy hair of light,

And dazzling eyes of glory, in whose form

The charms of Earth’s least mortal daughters grow

To an unearthly stature, in an essence 110

Of purer elements; while the hues of youth

(Carnation’d like a sleeping infant’s cheek

Rock’d by the beating of her mother’s heart, Or the rose tints, which summer’s twilight leaves

Upon the lofty glacier’s virgin snow,

The blush of earth embracing with her heaven)

Tinge thy celestial aspect, and make tame

The beauties of the sunbow which bends o’er thee.

Beautiful Spirit! in thy calm clear brow,

Wherein is glass’d serenity of soul, 120

Which of itself shows immortality,

I read that thou wilt pardon to a Son

Of Earth, whom the abstruser powers permit

At times to commune with them—if that he

Avail him of his spells—to call thee thus,

And gaze on thee a moment.

WITCH. Son of Earth!

I know thee, and the powers which give thee power;

I know thee for a man of many thoughts,

And deeds of good and ill, extreme in both,

Fatal and fated in thy sufferings. 130

I have expected this—what wouldst thou with me.

MANFRED. To look upon thy beauty—nothing further.

The face of the earth hath madden’d me, and I

Take refuge in her mysteries, and pierce

To the abodes of those who govern her—

But they can nothing aid me. I have sought

From them what they could not bestow, and now

I search no further.

WITCH. What could be the quest

Which is not in the power of the most powerful,

The rulers of the invisible?

MANFRED. A boon; 140

But why should I repeat it? ‘twere in vain.

WITCH. I know not that; let thy lips utter it.

MANFRED. Well, though it torture me, ‘t is but the same;

My pang shall find a voice. From my youth upwards

My spirit walk’d not with the souls of men,

Nor look’d upon the earth with human eyes;

The thirst of their ambition was not mine;

The aim of their existence was not mine;

My joys, my griefs, my passions, and my powers,

Made me a stranger; though I wore the form, 150

I had no sympathy with breathing flesh,

Nor midst the creatures of clay that girded me

Was there but one who—but of her anon.

I said with men, and with the thoughts of men,

I held but slight communion; but instead,

My joy was in the Wilderness, to breathe

The difficult air of the iced mountain’s top,

Where the birds dare not build, nor insect’s wing

Flit o’er the herbless granite; or to plunge

Into the torrent, and to roll along 160

On the swift whirl of the new breaking wave

Of river-stream, or ocean, in their flow.

In these my early strength exulted; or

To follow through the night the moving moon,

The stars and their development, or catch

The dazzling lightnings till my eyes grew dim;

Or to look, list’ning, on the scatter’d leaves,

While Autumn winds were at their evening song.

These were my pastimes, and to be alone;

For if the beings, of whom I was one,— 170

Hating to be so,—cross’d me in my path,

I felt myself degraded back to them,

And was all clay again. And then I dived,

In my lone wanderings, to the caves of death,

Searching its cause in its effect, and drew

From wither’d bones, and skulls, and heap’d up dust,

Conclusions most forbidden. Then I pass’d

The nights of years in sciences, untaught

Save in the old-time; and with time and toil,

And terrible ordeal, and such penance 180

As in itself hath power upon the air

And spirits that do compass air and earth,

Space, and the peopled infinite, I made

Mine eyes familiar with Eternity,

Such as, before me, did the Magi, and

He who from out their fountain dwellings raised

Eros and Anteros, at Gadara,

As I do thee,—and with my knowledge grew

The thirst of knowledge, and the power and joy

Of this most bright intelligence, until— 190

WITCH. Proceed.

MANFRED. Oh! I but thus prolonged my words,

Boasting these idle attributes, because

As I approach the core of my heart’s grief—

But to my task. I have not named to thee

Father or mother, mistress, friend, or being

With whom I wore the chain of human ties;

If I had such, they seem’d not such to me—

Yet there was one—

WITCH. Spare not thyself—proceed.

MANFRED. She was like me in lineaments—her eyes

Her hair, her features, all, to the very tone 200

Even of her voice, they said were like to mine;

But soften’d all, and temper’d into beauty;

She had the same lone thoughts and wanderings,

The quest of hidden knowledge, and a mind

To comprehend the universe: nor these

Alone, but with them gentler powers than mine,

Pity, and smiles, and tears—which I had not;

And tenderness—but that I had for her;

Humility—and that I never had.

Her faults were mine—her virtues were her own— 210

I loved her, and destroy’d her!

WITCH. With thy hand?

MANFRED. Not with my hand, but heart—which broke her heart;

It gazed on mine, and wither’d. I have shed

Blood, but not hers—and yet her blood was shed—

I saw, and could not stanch it.

WITCH. And for this—

A being of the race thou dost despise,

The order which thine own would rise above,

Mingling with us and ours, thou dost forego

The gifts of our great knowledge, and shrink’st back

To recreant mortality—Away! 220

MANFRED. Daughter of Air! I tell thee, since that hour—

But words are breath—look on me in my sleep,

Or watch my watchings—Come and sit by me!

My solitude is solitude no more,

But peopled with the Furies,—I have gnash’d

My teeth in darkness till returning morn,

Then cursed myself till sunset;—I have pray’d

For madness as a blessing—’tis denied me.

I have affronted death—but in the war

Of elements the waters shrunk from me, 230

And fatal things pass’d harmless—the cold hand

Of an all—pitiless demon held me back,

Back by a single hair, which would not break.

In fantasy, imagination, all

The affluence of my soul—which one day was

A Croesus in creation—I plunged deep,

But, like an ebbing wave, it dash’d me back

Into the gulf of my unfathom’d thought.

I plunged amidst mankind—Forgetfulness

I sought in all, save where ‘tis to be found, 240

And that I have to learn—my sciences,

My long pursued and superhuman art,

Is mortal here; I dwell in my despair—

And live—and live for ever.

WITCH. It may be

That I can aid thee.

MANFRED. To do this thy power

Must wake the dead, or lay me low with them.

Do so—in any shape—in any hour—

With any torture—so it be the last.

WITCH. That is not in my province; but if thou

Wilt swear obedience to my will, and do 250

My bidding, it may help thee to thy wishes.

MANFRED. I will not swear—Obey! and whom? the spirits

Whose presence I command, and be the slave

Of those who served me—Never!

WITCH. Is this all?

Hast thou no gentler answer?—Yet bethink thee,

And pause ere thou rejectest.

MANFRED. I have said it.

WITCH. Enough!—I may retire then—say!

MANFRED. Retire! [The WITCH disappears.]

MANFRED (alone). We are the fools of time and terror:

Days Steal on us and steal from us; yet we live,

Loathing our life, and dreading still to die. 260

In all the days of this detested yoke—

This vital weight upon the struggling heart,

Which sinks with sorrow, or beats quick with pain,

Or joy that ends in agony or faintness—

In all the days of past and future, for

In life there is no present, we can number

How few, how less than few, wherein the soul

Forbears to pant for death, and yet draws back

As from a stream in winter, though the chill

Be but a moment’s. I have one resource 270

Still in my science—I can call the dead,

And ask them what it is we dread to be:

The sternest answer can but be the Grave,

And that is nothing—if they answer not—

The buried Prophet answered to the Hag

Of Endor; and the Spartan Monarch drew

From the Byzantine maid’s unsleeping spirit

An answer and his destiny—he slew

That which he loved unknowing what he slew,

And died unpardon’d—though he call’d in aid 280

The Phyxian Jove, and in Phigalia roused

The Arcadian Evocators to compel

The indignant shadow to depose her wrath,

Or fix her term of vengeance—she replied

In words of dubious import, but fulfill’d.

If I had never lived, that which I love

Had still been living; had I never loved,

That which I love would still be beautiful—

Happy and giving happiness. What is she?

What is she now?—a sufferer for my sins— 290

A thing I dare not think upon—or nothing.

Within few hours I shall not call in vain—

Yet in this hour I dread the thing I dare:

Until this hour I never shrunk to gaze

On spirit, good or evil—now I tremble,

And feel a strange cold thaw upon my heart.

But I can act even what I most abhor,

And champion human fears.—The night approaches. [Exit.]

SCENE III

The Summit of the Jungfrau Mountain.

Enter FIRST DESTINY.

The moon is rising broad, and round, and bright;

And here on snows, where never human foot 300

Of common mortal trod, we nightly tread,

And leave no traces; o’er the savage sea,

The glassy ocean of the mountain ice,

We skim its rugged breakers, which put on

The aspect of a tumbling tempest’s foam,

Frozen in a moment—a dead whirlpool’s image.

And this most steep fantastic pinnacle,

The fretwork of some earthquake—where the clouds

Pause to repose themselves in passing by—

Is sacred to our revels, or our vigils; 310

Here do I wait my sisters, on our way

To the Hall of Arimanes, for to-night

Is our great festival—’t is strange they come not.

A Voice without, singing.

The Captive Usurper,

Hurl’d down from the throne,

Lay buried in torpor,

Forgotten and lone;

I broke through his slumbers,

I shiver’d his chain,

I leagued him with numbers— 320

He’s Tyrant again!

With the blood of a million he’ll answer my care,

With a nation’s destruction—his flight and despair.

Second Voice, without.

The ship sail’d on, the ship sail’d fast,

But I left not a sail, and I left not a mast;

There is not a plank of the hull or the deck,

And there is not a wretch to lament o’er his wreck;

Save one, whom I held, as he swam, by the hair,

And he was a subject well worthy my care;

A traitor on land, and a pirate at sea— 330

But I saved him to wreak further havoc for me!

FIRST DESTINY, answering.

The city lies sleeping;

The morn, to deplore it,

May dawn on it weeping:

Sullenly, slowly,

The black plague flew o’er it—

Thousands lie lowly;

Tens of thousands shall perish—

The living shall fly from

The sick they should cherish; 340

But nothing can vanquish

The touch that they die from.

Sorrow and anguish,

And evil and dread,

Envelope a nation—

The blest are the dead,

Who see not the sight

Of their own desolation;

This work of a night—

This wreck of a realm—this deed of my doing— 350

For ages I’ve done, and shall still be renewing!

Enter the SECOND and THIRD DESTINIES.

The Three.

Our hands contain the hearts of men,

Our footsteps are their graves:

We only give to take again

The spirits of our slaves!

FIRST DESTINY. Welcome!—Where’s Nemesis?

SECOND DESTINY. At some great work;

But what I know not, for my hands were full.

THIRD DESTINY. Behold she cometh.

Enter NEMESIS.

FIRST DESTINY. Say, where hast thou been? My sisters and thyself are slow to-night.

NEMESIS. l was detain’d repairing shattered thrones, 360

Marrying fools, restoring dynasties,

Avenging men upon their enemies,

And making them repent their own revenge;

Goading the wise to madness, from the dull

Shaping out oracles to rule the world

Afresh, for they were waxing out of date,

And mortals dared to ponder for themselves,

To weigh kings in the balance, and to speak

Of freedom, the forbidden fruit.—Away!

We have out said the hour—mount we our clouds! [Exeunt.] 370

SCENE IV

The Hall of ARIMANES.—ARIMANES on his Throne, a Globe of Fire, surrounded by the SPIRITS.

Hymn of the SPIRITS

Hail to our Master!—Prince of Earth and Air!—

Who walks the clouds and waters—in his hand

The sceptre of the elements, which tear

Themselves to chaos at his high command!

He breatheth—and a tempest shakes the sea;

He speaketh—and the clouds reply in thunder;

He gazeth—from his glance the sunbeams flee;

He moveth—earthquakes rend the world asunder.

Beneath his footsteps the volcanoes rise;

His shadow is the Pestilence; his path 380

The comets herald through the crackling skies;

And planets turn to ashes at his wrath.

To him War offers daily sacrifice;

To him Death pays his tribute; Life is his,

With all its infinite of agonies—

And his the spirit of whatever is!

Enter the DESTINIES and NEMESIS.

FIRST DESTINY. Glory to Arimanes! on the earth

His power increaseth—both my sisters did

His bidding, nor did I neglect my duty!

SECOND DESTINY. Glory to Arimanes! we who bow 390

The necks of men, bow down before his throne!

THIRD DESTINY. Glory to Arimanes!—we await His nod!

NEMESIS. Sovereign of Sovereigns! we are thine.

And all that liveth, more or less, is ours,

And most things wholly so; still to increase

Our power, increasing thine, demands our care,

And we are vigilant—Thy late commands

Have been fulfill’d to the utmost.

Enter MANFRED.

A SPIRIT. What is here?

A mortal!—Thou most rash and fatal wretch,

Bow down and worship!

SECOND SPIRIT. I do know the man— 400

A Magian of great power, and fearful skill!

THIRD SPIRIT. Bow down and worship, slave! What, know’st thou not

Thine and our Sovereign?—Tremble, and obey!

ALL THE SPIRITS. Prostrate thyself, and thy condemnèd clay,

Child of the Earth! or dread the worst.

MANFRED. I know it;

And yet ye see I kneel not.

FOURTH SPIRIT. ‘T will be taught thee.

MANFRED. ‘Tis taught already,—many a night on the earth,

On the bare ground, have I bow’d down my face,

And strew’d my head with ashes; I have known

The fulness of humiliation, for 410

I sunk before my vain despair, and knelt

To my own desolation.

FIFTH SPIRIT. Dost thou dare

Refuse to Arimanes on his throne

What the whole earth accords, beholding not

The terror of his Glory—Crouch! I say.

MANFRED. Bid him bow down to that which is above him,

The overruling Infinite—the Maker

Who made him not for worship—let him kneel,

And we will kneel together.

THE SPIRITS. Crush the worm!

Tear him in pieces!—

FIRST DESTINY. Hence! Avaunt!—he’s mine. 420

Prince of the Powers invisible! This man

Is of no common order, as his port

And presence here denote. His sufferings

Have been of an immortal nature, like

Our own; his knowledge and his powers and will,

As far as is compatible with clay,

Which clogs the ethereal essence, have been such

As clay hath seldom borne; his aspirations

Have been beyond the dwellers of the earth,

And they have only taught him what we know— 430

That knowledge is not happiness, and science

But an exchange of ignorance for that

Which is another kind of ignorance.

This is not all; the passions, attributes

Of earth and heaven, from which no power, nor being,

Nor breath from the worm upwards is exempt,

Have pierced his heart; and in their consequence

Made him a thing, which I, who pity not,

Yet pardon those who pity. He is mine,

And thine, it may be—be it so, or not, 440

No other Spirit in this region hath

A soul like his—or power upon his soul.

NEMESIS. What doth he here then?

FIRST DESTINY. Let him answer that.

MANFRED. Ye know what I have known; and without power

I could not be amongst ye: but there are

Powers deeper still beyond—I come in quest

Of such, to answer unto what I seek.

NEMESIS. What wouldst thou?

MANFRED. Thou canst not reply to me.

Call up the dead—my question is for them.

NEMESIS. Great Arimanes, doth thy will avouch 450

The wishes of this mortal?

ARIMANES. Yea.

NEMESIS. Whom wouldst thou Uncharnel?

MANFRED. One without a tomb—call up Astarte.

NEMESIS

Shadow! or Spirit!

Whatever thou art,

Which still doth inherit

The whole or a part

Of the form of thy birth,

Of the mould of thy clay

Which returned to the earth,— 460

Re-appear to the day!

Bear what thou borest,

The heart and the form,

And the aspect thou worest

Redeem from the worm.

Appear!—Appear!—Appear!

Who sent thee there requires thee here!

[The Phantom of ASTARTE rises and stands in the midst.]

MANFRED. Can this be death? there’s bloom upon her cheek;

But now I see it is no living hue,

But a strange hectic—like the unnatural red 470

Which Autumn plants upon the perish’d leaf.

It is the same! Oh, God! that I should dread

To look upon the same—Astarte!—No,

I cannot speak to her—but bid her speak—

Forgive me or condemn me.

NEMESIS

By the power which hath broken

The grave which enthrall’d thee,

Speak to him who hath spoken,

Or those who have call’d thee!

MANFRED. She is silent,

And in that silence I am more than answer’d. 480

NEMESIS. My power extends no further.

Prince of air! It rests with thee alone—command her voice.

ARIMANES. Spirit—obey this sceptre!

NEMESIS. Silent still!

She is not of our order, but belongs

To the other powers. Mortal! thy quest is vain,

And we are baffled also.

MANFRED. Hear me, hear me—

Astarte! my belovèd! speak to me;

I have so much endured—so much endure—

Look on me! the grave hath not changed thee more

Than I am changed for thee. Thou lovèdst me 490

Too much, as I loved thee: we were not made

To torture thus each other, though it were

The deadliest sin to love as we have loved.

Say that thou loath’st me not—that I do bear

This punishment for both—that thou wilt be

One of the blessèd—and that I shall die;

For hitherto all hateful things conspire

To bind me in existence—in a life

Which makes me shrink from immortality—

A future like the past. I cannot rest. 500

I know not what I ask, nor what I seek:

I feel but what thou art—and what I am;

And I would hear yet once before I perish

The voice which was my music—Speak to me!

For I have call’d on thee in the still night,

Startled the slumbering birds from the hush’d boughs,

And woke the mountain wolves, and made the caves

Acquainted with thy vainly echo’d name,

Which answer’d me—many things answer’d me—

Spirits and men—but thou wert silent all. 510

Yet speak to me! I have outwatch’d the stars,

And gazed o’er heaven in vain in search of thee.

Speak to me! I have wander’d o’er the earth,

And never found thy likeness—Speak to me!

Look on the fiends around—they feel for me:

I fear them not, and feel for thee alone.

Speak to me! though it be in wrath;—but say—

I reck not what—but let me hear thee once—

This once—once more!

PHANTOM OF ASTARTE. Manfred!

MANFRED. Say on, say on—

I live but in the sound—it is thy voice! 520

PHANTOM. Manfred! To-morrow ends thine earthly ills.

Farewell!

MANFRED. Yet one word more—am I forgiven?

PHANTOM. Farewell!

MANFRED. Say, shall we meet again?

PHANTOM. Farewell!

MANFRED. One word for mercy! Say, thou lovest me.

PHANTOM. Manfred! [The Spirit of ASTARTE departs.]

NEMESIS. She’s gone, and will not be recall’d;

Her words will be fulfill’d. Return to the earth.

A SPIRIT. He is convulsed—

This is to be a mortal

And seek the things beyond mortality.

ANOTHER SPIRIT. Yet, see, he mastereth himself, and makes

His torture tributary to his will. 530

Had he been one of us, he would have made

An awful spirit.

NEMESIS. Hast thou further question

Of our great sovereign, or his worshippers?

MANFRED. None.

NEMESIS. Then for a time farewell.

MANFRED. We meet then! Where? On the earth?—

Even as thou wilt: and for the grace accorded

I now depart a debtor. Fare ye well! [Exit MANFRED.]

(Scene closes.)

Act III

SCENE I

A Hall in the Castle of Manfred.

MANFRED and HERMAN.

MANFRED. What is the hour?

HERMAN. It wants but one till sunset,

And promises a lovely twilight.

MANFRED. Say,

Are all things so disposed of in the tower

As I directed?

HERMAN. All, my lord, are ready;

Here is the key and casket.

MANFRED. It is well:

Thou mayst retire. [Exit HERMAN.]

MANFRED (alone). There is a calm upon me—

Inexplicable stillness! which till now

Did not belong to what I knew of life.

If that I did not know philosophy

To be of all our vanities the motliest, 10

The merest word that ever fool’d the ear

From out the schoolman’s jargon, I should deem

The golden secret, the sought ‘Kalon,’ found,

And seated in my soul. It will not last,

But it is well to have known it, though but once:

It hath enlarged my thoughts with a new sense,

And I within my tablets would note down

That there is such a feeling. Who is there?

Re-enter HERMAN.

HERMAN. My lord, the abbot of St. Maurice craves

To greet your presence.

Enter the ABBOT OF ST. MAURICE.

ABBOT. Peace be with Count Manfred! 20

MANFRED. Thanks, holy father! welcome to these walls;

Thy presence honours them, and blesseth those

Who dwell within them.

ABBOT. Would it were so, Count!—

But I would fain confer with thee alone.

MANFRED. Herman, retire.—

What would my reverend guest?

ABBOT. Thus, without prelude:—Age and zeal, my office,

And good intent, must plead my privilege;

Our near, though not acquainted neighbourhood,

May also be my herald. Rumours strange,

And of unholy nature, are abroad, 30

And busy with thy name; a noble name

For centuries: may he who bears it now

Transmit it unimpair’d!

MANFRED. Proceed,—I listen.

ABBOT ‘T is said thou holdest converse with the things

Which are forbidden to the search of man;

That with the dwellers of the dark abodes,

The many evil and unheavenly spirits

Which walk the valley of the shade of death,

Thou communest. I know that with mankind,

Thy fellows in creation, thou dost rarely 40

Exchange thy thoughts, and that thy solitude

Is as an anchorite’s, were it but holy.

MANFRED. And what are they who do avouch these things?

ABBOT. My pious brethren, the scared peasantry,

Even thy own vassals, who do look on thee

With most unquiet eyes. Thy life’s in peril.

MANFRED. Take it.

ABBOT. I come to save, and not destroy.

I would not pry into thy secret soul;

But if these things be sooth, there still is time

For penitence and pity: reconcile thee 50

With the true church, and through the church to heaven.

MANFRED. I hear thee. This is my reply, whate’er

I may have been, or am, doth rest between

Heaven and myself; I shall not choose a mortal

To be my mediator. Have I sinn’d

Against your ordinances? prove and punish!

ABBOT. My son! I did not speak of punishment,

But penitence and pardon; with thyself

The choice of such remains—and for the last

Our institutions and our strong belief 60

Have given me power to smooth the path from sin

To higher hope and better thoughts, the first

I leave to heaven—’Vengeance is mine alone!’

So saith the Lord, and with all humbleness

His servant echoes back the awful word.

MANFRED. Old man! there is no power in holy men,

Nor charm in prayer, nor purifying form

Of penitence, nor outward look, nor fast,

Nor agony, nor, greater than all these,

The innate tortures of that deep despair 70

Which is remorse without the fear of hell

But all in all sufficient to itself

Would make a hell of heaven,—can exorcise

From out the unbounded spirit, the quick sense

Of its own sins, wrongs, sufferance, and revenge

Upon itself; there is no future pang

Can deal that justice on the self-condemn’d

He deals on his own soul.

ABBOT. All this is well;

For this will pass away, and be succeeded

By an auspicious hope, which shall look up 80

With calm assurance to that blessed place

Which all who seek may win, whatever be

Their earthly errors, so they be atoned:

And the commencement of atonement is

The sense of its necessity.—Say on—

And all our church can teach thee shall be taught;

And all we can absolve thee, shall be pardon’d.

MANFRED. When Rome’s sixth Emperor was near his last,

The victim of a self-inflicted wound,

To shun the torments of a public death 90

From senates once his slaves, a certain soldier,

With show of loyal pity, would have staunch’d

The gushing throat with his officious robe;

The dying Roman thrust him back and said—

Some empire still in his expiring glance—

‘It is too late—is this fidelity?’

ABBOT. And what of this?

MANFRED. I answer with the Roman— ‘It is too late!’

ABBOT. It never can be so,

To reconcile thyself with thy own soul,

And thy own soul with heaven. Hast thou no hope? 100

‘Tis strange—even those who do despair above,

Yet shape themselves some phantasy on earth,

To which frail twig they cling, like drowning men.

MANFRED. Ay—father! I have had those earthly visions

And noble aspirations in my youth,

To make my own the mind of other men,

The enlightener of nations; and to rise

I knew not whither—it might be to fall;

But fall, even as the mountain—cataract,

Which having leapt from its more dazzling height, 110

Even in the foaming strength of its abyss

(Which casts up misty columns that become

Clouds raining from the re-ascended skies)

Lies low but mighty still.—But this is past,

My thoughts mistook themselves.

ABBOT. And wherefore so?

MANFRED. I could not tame my nature down; for he

Must serve who fain would sway—and soothe, and sue,

And watch all time, and pry into all place,

And be a living lie, who would become

A mighty thing amongst the mean, and such 120

The mass are; I disdain’d to mingle with

A herd, though to be leader—and of wolves.

The lion is alone, and so am I.

ABBOT. And why not live and act with other men?

MANFRED. Because my nature was averse from life;

And yet not cruel; for I would not make,

But find a desolation. Like the wind,

The red—hot breath of the most lone Simoom,

Which dwells but in the desert, and sweeps o’er

The barren sands which bear no shrubs to blast 130

And revels o’er their wild and arid waves,

And seeketh not, so that it is not sought,

But being met is deadly,—such hath been

The course of my existence; but there came

Things in my path which are no more.

ABBOT. Alas!

I ‘gin to fear that thou art past all aid

From me and from my calling; yet so young,

I still would—

MANFRED. Look on me! there is an order

Of mortals on the earth, who do become

Old in their youth, and die ere middle age, 140

Without the violence of warlike death;

Some perishing of pleasure, some of study,

Some worn with toil, some of mere weariness,

Some of disease, and some insanity,

And some of wither’d or of broken hearts;

For this last is a malady which slays

More than are number’d in the lists of Fate,

Taking all shapes, and bearing many names.

Look upon me! for even of all these things

Have I partaken; and of all these things, 150

One were enough; then wonder not that I

Am what I am, but that I ever was,

Or, having been, that I am still on earth.

ABBOT. Yet, hear me still—

MANFRED. Old man! I do respect

Thine order, and revere thine years; I deem

Thy purpose pious, but it is in vain.

Think me not churlish; I would spare thyself,

Far more than me, in shunning at this time

All further colloquy; and so—farewell. [Exit MANFRED.]

ABBOT. This should have been a noble creature: he 160

Hath all the energy which would have made

A goodly frame of glorious elements,

Had they been wisely mingled; as it is,

It is an awful chaos—light and darkness,

And mind and dust—and passions and pure thoughts,

Mix’d, and contending without end or order,

All dormant or destructive. He will perish,

And yet he must not; I will try once more,

For such are worth redemption; and my duty

Is to dare all things for a righteous end. 170

I’ll follow him—but cautiously, though surely. [Exit ABBOT.]

SCENE II

Another Chamber.

MANFRED and HERMAN.

HERMAN. My Lord, you bade me wait on you at sunset:

He sinks beyond the mountain.

MANFRED. Doth he so?

I will look on him.

[MANFRED advances to the Window of the Hall.]

Glorious Orb! the idol

Of early nature, and the vigorous race

Of undiseased mankind the giant sons

Of the embrace of angels, with a sex

More beautiful than they, which did draw down

The erring spirits who can ne’er return;

Most glorious orb! that wert a worship, ere 180

The mystery of thy making was reveal’d!

Thou earliest minister of the Almighty,

Which gladden’d, on their mountain tops, the hearts

Of the Chaldean shepherds, till they pour’d

Themselves in orisons! Thou material God!

And representative of the Unknown,

Who chose thee for his shadow! Thou chief star!

Centre of many stars! which mak’st our earth

Endurable, and temperest the hues

And hearts of all who walk within thy rays! 190

Sire of the seasons! Monarch of the climes

And those who dwell in them! for near or far

Our inborn spirits have a tint of thee,

Even as our outward aspects;—thou dost rise,

And shine, and set in glory.

Fare thee well! I ne’er shall see thee more.

As my first glance Of love and wonder was for thee, then take

My latest look: thou wilt not beam on one

To whom the gifts of life and warmth have been

Of a more fatal nature. He is gone; 200

I follow. [Exit MANFRED.]

SCENE III

The Mountains.—The Castle of MANFRED at some distance.—A Terrace before a Tower.—Time, Twilight.

HERMAN, MANUEL, and other Dependants of MANFRED.

HERMAN. ‘T is strange enough; night after night, for years,

He hath pursued long vigils in this tower,

Without a witness. I have been within it,—

So have we all been oft-times; but from it

Or its contents, it were impossible

To draw conclusions absolute of aught

His studies tend to. To be sure, there is

One chamber where none enter: I would give

The fee of what I have to come these three years 210

To pore upon its mysteries.

MANUEL. ‘T were dangerous;

Content thyself with what thou know’st already.

HERMAN. Ah! Manuel! thou art elderly and wise,

And could’st say much; thou hast dwelt within the castle—

How many years is’t?

MANUEL. Ere Count Manfred’s birth,

I served his father, whom he nought resembles.

HERMAN. There be more sons in like predicament.

But wherein do they differ?

MANUEL. I speak not

Of features or of form, but mind and habits;

Count Sigismund was proud, but gay and free— 220

A warrior and a reveller; he dwelt not

With books and solitude, nor made the night

A gloomy vigil, but a festal time,

Merrier than day; he did not walk the rocks

And forests like a wolf, nor turn aside

From men and their delights.

HERMAN. Beshrew the hour,

But those were jocund times! I would that such

Would visit the old walls again; they look

As if they had forgotten them.

MANUEL. These walls

Must change their chieftain first. Oh! I have seen 230

Some strange things in them, Herman.

HERMAN. Come, be friendly; Relate me some to while away our watch: I’ve heard thee darkly speak of an event Which happen’d hereabouts, by this same tower.

MANUEL. That was a night indeed! I do remember

‘T was twilight, as it may be now, and such

Another evening; yon red cloud, which rests

On Eigher’s pinnacle, so rested then,—

So like that it might be the same; the wind

Was faint and gusty, and the mountain snows 240

Began to glitter with the climbing moon.

Count Manfred was, as now, within his tower,—

How occupied, we knew not, but with him

The sole companion of his wanderings

And watchings—her, whom of all earthly things

That lived, the only thing he seem’d to love,—

As he, indeed, by blood was bound to do,

The Lady Astarte, his—

Hush! who comes here?

Enter the ABBOT.

ABBOT. Where is your master?

HERMAN. Yonder in the tower.

ABBOT. I must speak with him.

MANUEL. ‘T is impossible; 250

He is most private, and must not be thus

Intruded on.

ABBOT. Upon myself I take

The forfeit of my fault, if fault there be—

But I must see him.

HERMAN. Thou hast seen him once This eve already.

ABBOT. Herman! I command thee,

Knock, and apprize the Count of my approach.

HERMAN. We dare not.

ABBOT. Then it seems I must be herald

Of my own purpose.

MANUEL. Reverend father, stop—

I pray you pause.

ABBOT. Why so?

MANUEL. But step this way,

And I will tell you further. [Exeunt.] 260

SCENE IV

Interior of the Tower.

MANFRED alone.

The stars are forth, the moon above the tops

Of the snow-shining mountains.—Beautiful!

I linger yet with Nature, for the night

Hath been to me a more familiar face

Than that of man; and in her starry shade

Of dim, and solitary loveliness,

I learn’d the language of another world.

I do remember me, that in my youth,

When I was wandering,—upon such a night

I stood within the Coloseum’s wall, 270

Midst the chief relics of almighty Rome.

The trees which grew along the broken arches

Waved dark in the blue midnight, and the stars

Shone through the rents of ruin; from afar

The watchdog bay’d beyond the Tiber; and

More near from out the Caesars’ palace came

The owl’s long cry, and, interruptedly,

Of distant sentinels the fitful song

Begun and died upon the gentle wind.

Some cypresses beyond the time—worn breach 280

Appear’d to skirt the horizon, yet they stood

Within a bowshot. Where the Caesars dwelt,

And dwell the tuneless birds of night, amidst

A grove which springs through levell’d battlements,

And twines its roots with the imperial hearths,

Ivy usurps the laurel’s place of growth;—

But the gladiators’ bloody Circus stands,

A noble wreck in ruinous perfection!

While Caesar’s chambers, and the Augustan halls

Grovel on earth in indistinct decay.— 290

And thou didst shine, thou rolling moon, upon

All this, and cast a wide and tender light,

Which soften’d down the hoar austerity

Of rugged desolation, and fill’d up,

As ‘twere anew, the gaps of centuries;

Leaving that beautiful which still was so,

And making that which was not, till the place

Became religion, and the heart ran o’er

With silent worship of the great of old,—

The dead, but sceptred sovereigns, who still rule 300

Our spirits from their urns.—

‘T was such a night!

‘T is strange that I recall it at this time;

But I have found our thoughts take wildest flight

Even at the moment when they should array

Themselves in pensive order.

Enter the ABBOT.

ABBOT. My good Lord!

I crave a second grace for this approach;

But yet let not my humble zeal offend

By its abruptness—all it hath of ill

Recoils on me; its good in the effect

May light upon your head—could I say heart— 310

Could I touch that, with words or prayers, I should

Recall a noble spirit which hath wander’d

But is not yet all lost.

MANFRED. Thou know’st me not;

My days are number’d, and my deeds recorded:

Retire, or ‘t will be dangerous—Away!

ABBOT. Thou dost not mean to menace me?

MANFRED. Not I;

I simply tell thee peril is at hand,

And would preserve thee.

ABBOT. What dost thou mean?

MANFRED. Look there! What dost thou see?

ABBOT. Nothing.

MANFRED. Look there, I say,

And steadfastly;—now tell me what thou seest? 320

ABBOT. That which should shake me—but I fear it not;

I see a dusk and awful figure rise,

Like an infernal god from out the earth;

His face wrapt in a mantle, and his form

Robed as with angry clouds: he stands between

Thyself and me—but I do fear him not.

MANFRED. Thou hast no cause; he shall not harm thee, but

His sight may shock thine old limbs into palsy.

I say to thee—Retire!

ABBOT. And, I reply,

Never—till I have battled with this fiend:— 330

What doth he here?

MANFRED. Why—ay—what doth he here?

I did not send for him,—he is unbidden.

ABBOT. Alas! lost mortal! what with guests like these

Hast thou to do? I tremble for thy sake:

Why doth he gaze on thee, and thou on him?

Ah! he unveils his aspect; on his brow

The thunder-scars are graven; from his eye

Glares forth the immortality of hell— Avaunt!—

MANFRED. Pronounce—what is thy mission?

SPIRIT. Come!

ABBOT. What art thou, unknown being? answer!—speak! 340

SPIRIT. The genius of this mortal.—Come! ‘t is time.

MANFRED. I am prepared for all things, but deny

The power which summons me. Who sent thee here?

SPIRIT. Thou’lt know anon—Come! Come!

MANFRED. I have commanded

Things of an essence greater far than thine,

And striven with thy masters. Get thee hence!

SPIRIT. Mortal! thine hour is come—Away! I say.

MANFRED. I knew, and know my hour is come, but not

To render up my soul to such as thee:

Away! I’ll die as I have lived—alone. 350

SPIRIT. Then I must summon up my brethren.—Rise

[Other spirits rise up.]

ABBOT. Avaunt! ye evil ones!—Avaunt! I say,—

Ye have no power where piety hath power,

And I do charge ye in the name—

SPIRIT. Old man!

We know ourselves, our mission, and thine order;

Waste not thy holy words on idle uses,

It were in vain; this man is forfeited.

Once more I summon him—Away! away!

MANFRED. I do defy ye,—though I feel my soul

Is ebbing from me, yet I do defy ye; 360

Nor will I hence, while I have earthly breath

To breathe my scorn upon ye—earthly strength

To wrestle, though with spirits; what ye take

Shall be ta’en limb by limb.

SPIRIT. Reluctant mortal!

Is this the Magian who would so pervade

The world invisible, and make himself

Almost our equal?—Can it be that thou

Art thus in love with life? the very life

Which made thee wretched!

MANFRED. Thou false fiend, thou liest!

My life is in its last hour,—that I know, 370

Nor would redeem a moment of that hour.

I do not combat against death, but thee

And thy surrounding angels; my past power

Was purchased by no compact with thy crew,

But by superior science—penance—daring,

And length of watching—strength of mind—and skill

In knowledge of our fathers when the earth

Saw men and spirits walking side by side

And gave ye no supremacy: I stand

Upon my strength—I do defy—deny— 380

Spurn back, and scorn ye!—

SPIRIT. But thy many crimes

Have made thee—

MANFRED. What are they to such as thee?

Must crimes be punish’d but by other crimes,

And greater criminals?—Back to thy hell!

Thou hast no power upon me, that I feel;

Thou never shalt possess me, that I know:

What I have done is done; I bear within

A torture which could nothing gain from thine.

The mind which is immortal makes itself

Requital for its good or evil thoughts, 390

Is its own origin of ill and end,

And its own place and time; its innate sense,

When stripp’d of this mortality, derives

No colour from the fleeting things without,

But is absorb’d in sufferance or in joy,

Born from the knowledge of its own desert.

Thou didst not tempt me, and thou couldst not tempt me;

I have not been thy dupe nor am thy prey,

But was my own destroyer, and will be

My own hereafter.—Back, ye baffled fiends! 400

The hand of death is on me—but not yours!

[The Demons disappear.]

ABBOT. Alas! how pale thou art—thy lips are white—

And thy breast heaves—and in thy gasping throat

The accents rattle. Give thy prayers to Heaven—

Pray—albeit but in thought,—but die not thus.

MANFRED. ‘T is over—my dull eyes can fix thee not;

But all things swim around me, and the earth

Heaves as it were beneath me. Fare thee well—

Give me thy hand.

ABBOT. Cold—cold—even to the heart—

But yet one prayer—Alas! how fares it with thee? 410

MANFRED. Old man! ‘t is not so difficult to die. [MANFRED expires.]