1.9: Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834)

- Page ID

- 41765

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Although brought up in a fairly conventional Anglican family—Coleridge’s father was vicar of his parish and master of a grammar school—and expected to enter the clergy, Samuel Taylor Coleridge explored radical religious and social thought from his days at Jesus College, University of Cambridge onward. He sympathized with Unitarian beliefs and utopian democratic societies. He and his friend Robert Southey (1774-1843) conceived of a government based on pantisocracy, that is, equal government by all, and planned to set up a commune on the shores of the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania. To forward this goal, Southey married Edith Fricker (1774-1837), and Coleridge married her sister Sara Fricker (1802-1852). Although he never realized his pantisocratic society, Coleridge’s marriage to Sara endured, unhappily.

Another friendship that crucially shaped Coleridge’s career was that with Wordsworth, whom he met in 1795. They collaborated on Lyrical Ballads, to which Coleridge contributed “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” Coleridge traveled with Wordsworth to Germany where Coleridge learned the German language and read and translated important philosophical texts by Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), Friedrich von Schelling (1775-1854), Jakob Boehme (1575-1624), and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781). Their thought informed his subsequent prose and poetic works, and Coleridge is known for introducing the new German critical philosophy to England.

His most esteemed prose work is Biographia Literaria (1817), written as counterpoint to Wordsworth’s Preface to The Lyrical Ballads. In it, he famously defined imagination as a unifying power, as the means by which finite individuals commune with the infinite. In Biographia Literaria, Coleridge also explained the approach he and Wordsworth took to their respective contributions. He and Wordsworth decided on two types of poems for Lyrical Ballads, both of which would effectively reveal the imagination in action.

Wordsworth would take natural (or real) incidents and situations and make them seem supernatural (or unreal), while Coleridge would take supernatural incidents and situations and make them seem natural. Wordsworth desired a reciprocal relationship with nature. Coleridge, on the other hand, desired what might be described as circularity. From Kant, Coleridge learned that objectivity is subjectivity, that is, based on relativity. Kant led to Sartre’s Existentialism. Coleridge feared some sense of separation due to his own, possibly extreme, subjectivity/relativity, self-absorption, or what came to be termed solipsism. In most of his poetry, he seeks to recover unity, to unify what has been separated. For him, a break with unity leads to death-in-life.

Wordsworth would take natural (or real) incidents and situations and make them seem supernatural (or unreal), while Coleridge would take supernatural incidents and situations and make them seem natural. Wordsworth desired a reciprocal relationship with nature. Coleridge, on the other hand, desired what might be described as circularity. From Kant, Coleridge learned that objectivity is subjectivity, that is, based on relativity. Kant led to Sartre’s Existentialism. Coleridge feared some sense of separation due to his own, possibly extreme, subjectivity/relativity, self-absorption, or what came to be termed solipsism. In most of his poetry, he seeks to recover unity, to unify what has been separated. For him, a break with unity leads to death-in-life.

His poems express radical views on the mutuality of humans and nature, of divinity, of imagination, and of poetry itself. In “The Eolian Harp,” he makes what conservative contemporaries, including Coleridge’s wife, would consider an irreligious claim that all animated beings in nature and the world have the ability to give voice to God. The Rime of the Ancient Mariner explores a psychological landscape of separation and solitude, sin and redemption in natural—rather than institutional—terms. In “Kubla Khan” the poetic vision synthesizes opposites of the sunny and the dark, the inner and the outer life (caves and dome) into a powerful, paradisiacal harmony.

This latter poem is famous, or infamous, for having apparently been written while Coleridge was under the influence of opium. Opium was then commonly used as a pain-killer; it was prescribed to Coleridge to relieve his chronic back pain. He became addicted to the drug, an addiction from which he was never free, though later in his life it was controlled with the help of Dr. James Gilman. It’s impossible to say to what extent, if any, Coleridge’s addiction affected his productivity. Coleridge claims that “Kubla Khan” is an unfinished poem. Yet, it is remarkably complete, with its last stanza referring back to the first. Coleridge may have had a self-protective desire for his radical views not to be taken too seriously. His views are indeed radical; and he takes his readers to the threshold of a new world that seems to be meant for others, but not himself.

1.9.1: “The Eolian Harp”

Composed at Clevedon, Somersetshire

My pensive Sara! thy soft cheek reclined

Thus on mine arm, most soothing sweet it is

To sit beside our cot, our cot o’ergrown

With white-flower’d Jasmin, and the broad-leav’d Myrtle,

(Meet emblems they of Innocence and Love!)

And watch the clouds, that late were rich with light,

Slow saddening round, and mark the star of eve

Serenely brilliant (such should Wisdom be)

Shine opposite! How exquisite the scents

Snatch’d from yon bean-field! and the world so hushed!

The stilly murmur of the distant

Sea Tells us of silence.

And that simplest Lute,

Plac’d length-ways in the clasping casement, hark!

How by the desultory breeze caressed,

Like some coy maid half yielding to her lover,

It pours such sweet upbraiding, as must needs

Tempt to repeat the wrong! And now, its strings

Boldlier swept, the long sequacious notes

Over delicious surges sink and rise,

Such a soft floating witchery of sound

As twilight Elfins make, when they at eve

Voyage on gentle gales from Fairy-Land,

Where Melodies round honey-dropping flowers,

Footless and wild, like birds of Paradise,

Nor pause, nor perch, hovering on untamed wing!

O the one Life within us and abroad,

Which meets all motion and becomes its soul,

A light in sound, a sound-like power in light,

Rhythm in all thought, and joyance every where—

Methinks, it should have been impossible

Not to love all things in a world so filled;

Where the breeze warbles, and the mute still air

Is Music slumbering on her instrument.

And thus, my love! as on the midway slope

Of yonder hill I stretch my limbs at noon,

Whilst through my half-closed eye-lids I behold

The sunbeams dance, like diamonds, on the main,

And tranquil muse upon tranquillity;

Full many a thought uncalled and undetained,

And many idle flitting phantasies,

Traverse my indolent and passive brain,

As wild and various as the random gales

That swell and flutter on this subject lute!

And what if all of animated nature

Be but organic Harps diversely framed,

That tremble into thought, as o’er them sweeps

Plastic and vast, one intellectual breeze,

At once the Soul of each, and God of all?

But thy more serious eye a mild reproof

Darts, O belovéd woman! nor such thoughts

Dim and unhallowed dost thou not reject,

And biddest me walk humbly with my God.

Meek Daughter in the family of Christ!

Well hast thou said and holily dispraised

These shapings of the unregenerate mind;

Bubbles that glitter as they rise and break

On vain Philosophy’s aye-babbling spring.

For never guiltless may I speak of him,

The Incomprehensible! save when with awe

I praise him, and with Faith that inly feels;

Who with his saving mercies healéd me,

A sinful and most miserable man,

Wildered and dark, and gave me to possess

Peace, and this cot, and thee, heart-honour’d Maid!

1.9.2: “Frost at Midnight”

The Frost performs its secret ministry,

Unhelped by any wind. The owlet’s cry

Came loud–and hark, again! loud as before.

The inmates of my cottage, all at rest,

Have left me to that solitude, which suits

Abstruser musings: save that at my side

My cradled infant slumbers peacefully.

‘Tis calm indeed! so calm, that it disturbs

And vexes meditation with its strange

And extreme silentness. Sea, hill, and wood,

This populous village! Sea, and hill, and wood,

With all the numberless goings-on of life,

Inaudible as dreams! the thin blue flame

Lies on my low-burnt fire, and quivers not;

Only that film, which fluttered on the grate,

Still flutters there, the sole unquiet thing.

Methinks, its motion in this hush of nature

Gives it dim sympathies with me who live,

Making it a companionable form,

Whose puny flaps and freaks the idling Spirit

By its own moods interprets, every where

Echo or mirror seeking of itself,

And makes a toy of Thought.

But O! how oft,

How oft, at school, with most believing mind,

Presageful, have I gazed upon the bars,

To watch that fluttering stranger! and as oft

With unclosed lids, already had I dreamt

Of my sweet birth-place, and the old church-tower,

Whose bells, the poor man’s only music, rang

From morn to evening, all the hot Fair-day,

So sweetly, that they stirred and haunted me

With a wild pleasure, falling on mine ear

Most like articulate sounds of things to come!

So gazed I, till the soothing things, I dreamt,

Lulled me to sleep, and sleep prolonged my dreams!

And so I brooded all the following morn,

Awed by the stern preceptor’s face, mine eye

Fixed with mock study on my swimming book:

Save if the door half opened, and I snatched

A hasty glance, and still my heart leaped up,

For still I hoped to see the stranger’s face,

Townsman, or aunt, or sister more beloved,

My play-mate when we both were clothed alike!

Dear Babe, that sleepest cradled by my side,

Whose gentle breathings, heard in this deep calm,

Fill up the intersperséd vacancies

And momentary pauses of the thought!

My babe so beautiful! it thrills my heart

With tender gladness, thus to look at thee,

And think that thou shalt learn far other lore,

And in far other scenes! For I was reared

In the great city, pent ‘mid cloisters dim,

And saw nought lovely but the sky and stars.

But thou, my babe! shalt wander like a breeze

By lakes and sandy shores, beneath the crags

Of ancient mountain, and beneath the clouds,

Which image in their bulk both lakes and shores

And mountain crags: so shalt thou see and hear

The lovely shapes and sounds intelligible

Of that eternal language, which thy God

Utters, who from eternity doth teach

Himself in all, and all things in himself.

Great universal Teacher! he shall mould

Thy spirit, and by giving make it ask.

Therefore all seasons shall be sweet to thee,

Whether the summer clothe the general earth

With greenness, or the redbreast sit and sing

Betwixt the tufts of snow on the bare branch

Of mossy apple-tree, while the nigh thatch

Smokes in the sun-thaw; whether the eave-drops fall

Heard only in the trances of the blast,

Or if the secret ministry of frost

Shall hang them up in silent icicles,

Quietly shining to the quiet Moon.

1.9.3: “Kubla Khan; or A Vision in a Dream”

A fragment.

In the summer of the year 1797, the Author, then in ill health, had retired to a lonely farm-house between Porlock and Linton, on the Exmoor confines of Somerset and Devonshire. In consequence of a slight indisposition, an anodyne had been prescribed, from the effect of which he fell asleep in his chair at the moment he was reading the following sentence, or words of the same substance, in “Purchas’s Pilgrimage:”—”Here the Khan Kubla commanded a palace to be built, and a stately garden thereunto: and thus ten miles of fertile ground were inclosed with a wall.” The author continued for about three hours in a profound sleep, at least of the external senses, during which time he has the most vivid confidence that he could not have composed less than from two to three hundred lines; if that indeed can be called composition in which all the images rose up before him as things, with a parallel production of the correspondent expressions, without any sensation or consciousness of effort. On awaking he appeared to himself to have a distinct recollection of the whole, and taking his pen, ink, and paper, instantly and eagerly wrote down the lines that are here preserved. At this moment he was unfortunately called out by a person on business from Porlock, and detained by him above an hour, and on his return to his room, found, to his no small surprise and mortification, that though he still retained some vague and dim recollection of the general purport of the vision, yet, with the exception of some eight or ten scattered lines and images, all the rest had passed away like the images on the surface of a stream into which a stone had been cast, but, alas! without the after restoration of the latter.

Then all the charm

Is broken—all that phantom-world so fair

Vanishes, and a thousand circlets spread,

And each mis-shape the other.

Stay awhile, Poor youth

I who scarcely dar’st lift up thine eyes—

The stream will soon renew its smoothness, soon

The visions will return! And lo! he stays,

And soon the fragments dim of lovely forms

Come trembling back, unite, and now once more

The pool becomes a mirror.

Yet from the still surviving recollections in his mind, the Author has frequently purposed to finish for himself what had been originally, as it were, given to him. [I shall sing a sweeter song today]: but the to-morrow is yet to come.

1816.

IN Xanadu did Kubla Khan A stately pleasure-dome decree: Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

So twice five miles of fertile ground

With walls and towers were girdled round

And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills

Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree;

And here were forests ancient as the hills,

Enfolding sunny spots of greenery.

But oh! that deep romantic chasm which slanted

Down the green hill athwart a cedarn cover!

A savage place! as holy and enchanted

As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted

By woman wailing for her demon-lover!

And from this chasm, with ceaseless turmoil seething,

As if this earth in fast thick pants were breathing,

A mighty fountain momently was forced;

Amid whose swift half-intermitted burst

Huge fragments vaulted like rebounding hail,

Or chaffy grain beneath the thresher’s flail:

And ‘mid these dancing rocks at once and ever

It flung up momently the sacred river.

Five miles meandering with a mazy motion

Through wood and dale the sacred river ran,

Then reached the caverns measureless to man,

And sank in tumult to a lifeless ocean:

And ‘mid this tumult Kubla heard from far

Ancestral voices prophesying war!

The shadow of the dome of pleasure

Floated midway on the waves;

Where was heard the mingled measure

From the fountain and the caves.

It was a miracle of rare device,

A sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice!

A damsel with a dulcimer

In a vision once I saw:

It was an Abyssinian maid,

And on her dulcimer she played,

Singing of Mount Abora.

Could I revive within me Her symphony and song,

To such a deep delight ‘twould win me

That with music loud and long,

I would build that dome in air,

That sunny dome! those caves of ice!

And all who heard should see them there,

And all should cry, Beware! Beware!

His flashing eyes, his floating hair!

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread,

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise.

1.9.4: “Dejection: An Ode”

Late, late yestreen I saw the new Moon,

With the old Moon in her arms;

And I fear, I fear, my Master dear!

We shall have a deadly storm.

“Ballad of Sir Patrick Spence”

I

Well! If the Bard was weather-wise, who made

The grand old ballad of Sir Patrick Spence,

This night, so tranquil now, will not go hence

Unroused by winds, that ply a busier trade

Than those which mould yon cloud in lazy flakes,

Or the dull sobbing draft, that moans and rakes

Upon the strings of this Æolian lute,

Which better far were mute.

For lo! the New-moon winter-bright!

And overspread with phantom light,

(With swimming phantom light o’erspread

But rimmed and circled by a silver thread)

I see the old Moon in her lap, foretelling

The coming-on of rain and squally blast.

And oh ! that even now the gust were swelling,

And the slant night-shower driving loud and fast!

Those sounds which oft have raised me, whilst they awed,

And sent my soul abroad,

Might now perhaps their wonted impulse give,

Might startle this dull pain, and make it move and live!

II

A grief without a pang, void, dark, and drear,

A stifled, drowsy, unimpassioned grief,

Which finds no natural outlet, no relief,

In word, or sigh, or tear—

O Lady! in this wan and heartless mood,

To other thoughts by yonder throstle woo’d,

All this long eve, so balmy and serene,

Have I been gazing on the western sky,

And its peculiar tint of yellow green :

And still I gaze—and with how blank an eye!

And those thin clouds above, in flakes and bars,

That give away their motion to the stars;

Those stars, that glide behind them or between,

Now sparkling, now bedimmed, but always seen:

Yon crescent Moon, as fixed as if it grew

In its own cloudless, starless lake of blue;

I see them all so excellently fair,

I see, not feel how beautiful they are!

III

My genial spirits fail;

And what can these avail

To lift the smothering weight from off my breast?

It were a vain endeavour,

Though I should gaze for ever

On that green light that lingers in the west:

I may not hope from outward forms to win

The passion and the life, whose fountains are within.

IV

O Lady! we receive but what we give,

And in our life alone does nature live:

Ours is her wedding-garment, ours her shroud!

And would we aught behold, of higher worth,

Than that inanimate cold world allowed

To the poor loveless ever-anxious crowd,

Ah! from the soul itself must issue forth,

A light, a glory, a fair luminous cloud

Enveloping the Earth—

And from the soul itself must there be sent

A sweet and potent voice, of its own birth,

Of all sweet sounds the life and element!

V

O pure of heart! thou need’st not ask of me

What this strong music in the soul may be!

What, and wherein it doth exist,

This light, this glory, this fair luminous mist,

This beautiful and beauty-making power.

Joy, virtuous Lady! Joy that ne’er was given,

Save to the pure, and in their purest hour,

Life, and Life’s effluence, cloud at once and shower,

Joy, Lady! is the spirit and the power,

Which wedding Nature to us gives in dower

A new Earth and new Heaven,

Undreamt of by the sensual and the proud—

Joy is the sweet voice, Joy the luminous cloud—

We in ourselves rejoice!

And thence flows all that charms or ear or sight,

All melodies the echoes of that voice,

All colours a suffusion from that light.

VI

There was a time when, though my path was rough,

This joy within me dallied with distress,

And all misfortunes were but as the stuff

Whence Fancy made me dreams of happiness:

For hope grew round me, like the twining vine,

And fruits, and foliage, not my own, seemed mine.

But now afflictions bow me down to earth:

Nor care I that they rob me of my mirth;

But oh! each visitation

Suspends what nature gave me at my birth,

My shaping spirit of Imagination.

For not to think of what I needs must feel,

But to be still and patient, all I can;

And haply by abstruse research to steal

From my own nature all the natural man—

This was my sole resource, my only plan:

Till that which suits a part infects the whole,

And now is almost grown the habit of my soul.

VII

Hence, viper thoughts, that coil around my mind,

Reality’s dark dream!

I turn from you, and listen to the wind,

Which long has raved unnoticed. What a scream

Of agony by torture lengthened out

That lute sent forth! Thou Wind, that rav’st without,

Bare crag, or mountain-tairn(1), or blasted tree,

Or pine-grove whither woodman never clomb,

Or lonely house, long held the witches’ home,

Methinks were fitter instruments for thee,

Mad Lutanist! who in this month of showers,

Of dark-brown gardens, and of peeping flowers,

Mak’st Devils’ yule, with worse than wintry song,

The blossoms, buds, and timorous leaves among.

Thou Actor, perfect in all tragic sounds!

Thou mighty Poet, e’en to frenzy bold!

What tell’st thou now about?

‘Tis of the rushing of a host in rout,

With groans of trampled men, with smarting wounds—

At once they groan with pain, and shudder with the cold!

But hush! there is a pause of deepest silence!

And all that noise, as of a rushing crowd,

With groans, and tremulous shudderings—all is over—

It tells another tale, with sounds less deep and loud!

A tale of less affright,

And tempered with delight,

As Otway’s self had framed the tender lay,

‘Tis of a little child

Upon a lonesome wild,

Not far from home, but she hath lost her way:

And now moans low in bitter grief and fear,

And now screams loud, and hopes to make her mother hear.

VIII

‘Tis midnight, but small thoughts have I of sleep:

Full seldom may my friend such vigils keep!

Visit her, gentle Sleep! with wings of healing,

And may this storm be but a mountain-birth,

May all the stars hang bright above her dwelling,

Silent as though they watched the sleeping Earth!

With light heart may she rise,

Gay fancy, cheerful eyes,

Joy lift her spirit, joy attune her voice;

To her may all things live, from the pole to pole,

Their life the eddying of her living soul!

O simple spirit, guided from above,

Dear Lady! friend devoutest of my choice,

Thus may’st thou ever, evermore rejoice.

1.9.5: The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Part The First

It is an ancient Mariner,

And he stoppeth one of three.

“By thy long grey beard and glittering eye,

Now wherefore stopp’st thou me?

“The Bridegroom’s doors are opened wide,

And I am next of kin;

The guests are met, the feast is set:

May’st hear the merry din.”

He holds him with his skinny hand, “

There was a ship,” quoth he.

“Hold off! unhand me, grey-beard loon!”

Eftsoons his hand dropt he.

He holds him with his glittering eye—

The Wedding-Guest stood still,

And listens like a three years child:

The Mariner hath his will.

The Wedding-Guest sat on a stone:

He cannot choose but hear;

And thus spake on that ancient man,

The bright-eyed Mariner.

The ship was cheered, the harbour cleared,

Merrily did we drop

Below the kirk, below the hill,

Below the light-house top.

The Sun came up upon the left,

Out of the sea came he!

And he shone bright, and on the right

Went down into the sea.

Higher and higher every day,

Till over the mast at noon—

The Wedding-Guest here beat his breast,

For he heard the loud bassoon.

The bride hath paced into the hall,

Red as a rose is she;

Nodding their heads before her goes

The merry minstrelsy.

The Wedding-Guest he beat his breast,

Yet he cannot chuse but hear;

And thus spake on that ancient man,

The bright-eyed Mariner.

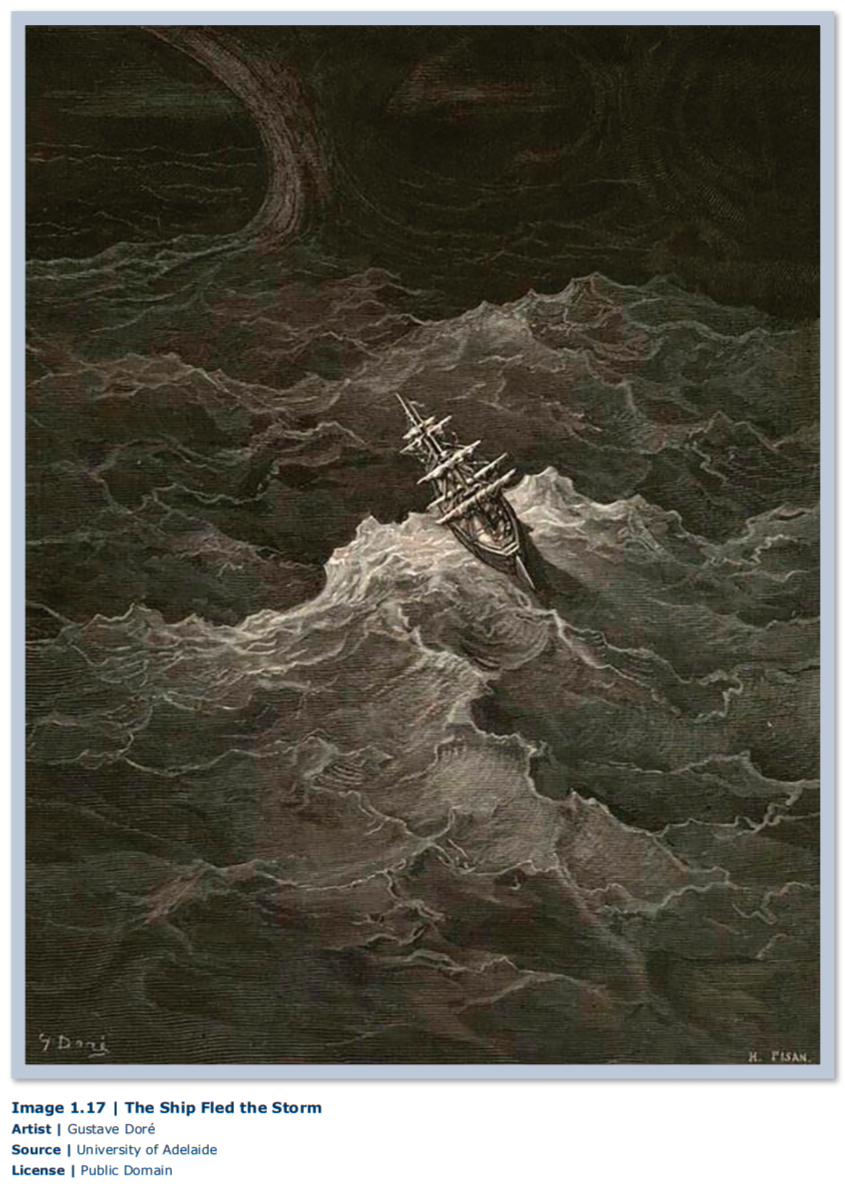

And now the STORM-BLAST came, and he

Was tyrannous and strong:

He struck with his o’ertaking wings,

And chased south along.

With sloping masts and dipping prow,

As who pursued with yell and blow

Still treads the shadow of his foe

And forward bends his head,

The ship drove fast, loud roared the blast,

And southward aye we fled.

And now there came both mist and snow,

And it grew wondrous cold:

And ice, mast-high, came floating by,

As green as emerald.

And through the drifts the snowy clifts

Did send a dismal sheen:

Nor shapes of men nor beasts we ken—

The ice was all between.

The ice was here, the ice was there,

The ice was all around:

It cracked and growled, and roared and howled,

Like noises in a swound!

At length did cross an Albatross:

Thorough the fog it came;

As if it had been a Christian soul,

We hailed it in God’s name.

It ate the food it ne’er had eat,

And round and round it flew.

The ice did split with a thunder-fit;

The helmsman steered us through!

And a good south wind sprung up behind;

The Albatross did follow,

And every day, for food or play,

Came to the mariners’ hollo!

In mist or cloud, on mast or shroud,

It perched for vespers nine;

Whiles all the night, through fog-smoke white,

Glimmered the white Moon-shine.

“God save thee, ancient Mariner!

From the fiends, that plague thee thus!—

Why look’st thou so?”—

With my cross-bow I shot the ALBATROSS.

Part The Second

The Sun now rose upon the right:

Out of the sea came he,

Still hid in mist, and on the left

Went down into the sea.

And the good south wind still blew behind

But no sweet bird did follow,

Nor any day for food or play

Came to the mariners’ hollo!

And I had done an hellish thing,

And it would work ‘em woe:

For all averred, I had killed the bird

That made the breeze to blow.

Ah wretch! said they, the bird to slay

That made the breeze to blow!

Nor dim nor red, like God’s own head,

The glorious Sun uprist:

Then all averred, I had killed the bird

That brought the fog and mist.

‘Twas right, said they, such birds to slay,

That bring the fog and mist.

The fair breeze blew, the white foam flew,

The furrow followed free:

We were the first that ever burst

Into that silent sea.

Down dropt the breeze, the sails dropt down,

‘Twas sad as sad could be;

And we did speak only to break

The silence of the sea!

All in a hot and copper sky,

The bloody Sun, at noon,

Right up above the mast did stand,

No bigger than the Moon.

Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, nor breath nor motion;

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean.

Water, water, every where,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, every where,

Nor any drop to drink.

The very deep did rot: O Christ!

That ever this should be!

Yea, slimy things did crawl with legs

Upon the slimy sea.

About, about, in reel and rout

The death-fires danced at night;

The water, like a witch’s oils,

Burnt green, and blue and white.

And some in dreams assured were

Of the spirit that plagued us so:

Nine fathom deep he had followed us

From the land of mist and snow.

And every tongue, through utter drought,

Was withered at the root;

We could not speak, no more than if

We had been choked with soot.

Ah! well a-day! what evil looks

Had I from old and young!

Instead of the cross, the Albatross

About my neck was hung.

Part The Third

There passed a weary time.

Each throat Was parched, and glazed each eye.

A weary time! a weary time!

How glazed each weary eye,

When looking westward, I beheld

A something in the sky.

At first it seemed a little speck,

And then it seemed a mist:

It moved and moved, and took at last

A certain shape, I wist.

A speck, a mist, a shape, I wist!

And still it neared and neared:

As if it dodged a water-sprite,

It plunged and tacked and veered.

With throats unslaked, with black lips baked,

We could not laugh nor wail;

Through utter drought all dumb we stood!

I bit my arm, I sucked the blood,

And cried, A sail! a sail!

With throats unslaked, with black lips baked,

Agape they heard me call:

Gramercy! they for joy did grin,

And all at once their breath drew in,

As they were drinking all.

See! see! (I cried) she tacks no more!

Hither to work us weal;

Without a breeze, without a tide,

She steadies with upright keel!

The western wave was all a-flame

The day was well nigh done!

Almost upon the western wave

Rested the broad bright Sun;

When that strange shape drove suddenly

Betwixt us and the Sun.

And straight the Sun was flecked with bars,

(Heaven’s Mother send us grace!)

As if through a dungeon-grate he peered,

With broad and burning face.

Alas! (thought I, and my heart beat loud)

How fast she nears and nears!

Are those her sails that glance in the Sun,

Like restless gossameres!

Are those her ribs through which the Sun

Did peer, as through a grate?

And is that Woman all her crew?

Is that a DEATH? and are there two?

Is DEATH that woman’s mate?

Her lips were red, her looks were free,

Her locks were yellow as gold:

Her skin was as white as leprosy,

The Night-Mare LIFE-IN-DEATH was she,

Who thicks man’s blood with cold.

The naked hulk alongside came,

And the twain were casting dice;

“The game is done! I’ve won! I’ve won!”

Quoth she, and whistles thrice.

The Sun’s rim dips; the stars rush out:

At one stride comes the dark;

With far-heard whisper, o’er the sea.

Off shot the spectre-bark.

We listened and looked sideways up!

Fear at my heart, as at a cup,

My life-blood seemed to sip!

The stars were dim, and thick the night,

The steersman’s face by his lamp gleamed white;

From the sails the dew did drip—

Till clombe above the eastern bar

The horned Moon, with one bright star

Within the nether tip.

One after one, by the star-dogged Moon

Too quick for groan or sigh,

Each turned his face with a ghastly pang,

And cursed me with his eye.

Four times fifty living men,

(And I heard nor sigh nor groan)

With heavy thump, a lifeless lump,

They dropped down one by one.

The souls did from their bodies fly,—

They fled to bliss or woe!

And every soul, it passed me by,

Like the whizz of my CROSS-BOW!

Part The Fourth

“I fear thee, ancient Mariner!

I fear thy skinny hand!

And thou art long, and lank, and brown,

As is the ribbed sea-sand.

“I fear thee and thy glittering eye,

And thy skinny hand, so brown.”—

Fear not, fear not, thou Wedding-Guest!

This body dropt not down.

Alone, alone, all, all alone,

Alone on a wide wide sea!

And never a saint took pity on

My soul in agony.

The many men, so beautiful!

And they all dead did lie:

And a thousand thousand slimy things

Lived on; and so did I

I looked upon the rotting sea,

And drew my eyes away;

I looked upon the rotting deck,

And there the dead men lay.

I looked to Heaven, and tried to pray:

But or ever a prayer had gusht,

A wicked whisper came, and made

my heart as dry as dust.

I closed my lids, and kept them close,

And the balls like pulses beat;

For the sky and the sea, and the sea and the sky

Lay like a load on my weary eye,

And the dead were at my feet.

The cold sweat melted from their limbs,

Nor rot nor reek did they:

The look with which they looked on me

Had never passed away.

An orphan’s curse would drag to Hell

A spirit from on high;

But oh! more horrible than that

Is a curse in a dead man’s eye!

Seven days, seven nights, I saw that curse,

And yet I could not die.

The moving Moon went up the sky,

And no where did abide:

Softly she was going up,

And a star or two beside.

Her beams bemocked the sultry main,

Like April hoar-frost spread;

But where the ship’s huge shadow lay,

The charmed water burnt alway

A still and awful red.

Beyond the shadow of the ship,

I watched the water-snakes:

They moved in tracks of shining white,

And when they reared, the elfish light

Fell off in hoary flakes.

Within the shadow of the ship

I watched their rich attire:

Blue, glossy green, and velvet black,

They coiled and swam; and every track

Was a flash of golden fire.

O happy living things! no tongue

Their beauty might declare:

A spring of love gushed from my heart,

And I blessed them unaware:

Sure my kind saint took pity on me,

And I blessed them unaware.

The self same moment I could pray;

And from my neck so free

The Albatross fell off, and sank

Like lead into the sea.

Part The Fifth

Oh sleep! it is a gentle thing,

Beloved from pole to pole!

To Mary Queen the praise be given!

She sent the gentle sleep from Heaven,

That slid into my soul.

The silly buckets on the deck,

That had so long remained,

I dreamt that they were filled with dew;

And when I awoke, it rained.

My lips were wet, my throat was cold,

My garments all were dank;

Sure I had drunken in my dreams,

And still my body drank.

I moved, and could not feel my limbs:

I was so light—almost

I thought that I had died in sleep,

And was a blessed ghost.

And soon I heard a roaring wind:

It did not come anear;

But with its sound it shook the sails,

That were so thin and sere.

The upper air burst into life!

And a hundred fire-flags sheen,

To and fro they were hurried about!

And to and fro, and in and out,

The wan stars danced between.

And the coming wind did roar more loud,

And the sails did sigh like sedge;

And the rain poured down from one black cloud;

The Moon was at its edge.

The thick black cloud was cleft, and still

The Moon was at its side:

Like waters shot from some high crag,

The lightning fell with never a jag,

A river steep and wide.

The loud wind never reached the ship,

Yet now the ship moved on!

Beneath the lightning and the Moon

The dead men gave a groan.

They groaned, they stirred, they all uprose,

Nor spake, nor moved their eyes;

It had been strange, even in a dream,

To have seen those dead men rise.

The helmsman steered, the ship moved on;

Yet never a breeze up blew;

The mariners all ‘gan work the ropes,

Where they were wont to do:

They raised their limbs like lifeless tools—

We were a ghastly crew.

The body of my brother’s son,

Stood by me, knee to knee:

The body and I pulled at one rope,

But he said nought to me.

“I fear thee, ancient Mariner!”

Be calm, thou Wedding-Guest!

‘Twas not those souls that fled in pain,

Which to their corses came again,

But a troop of spirits blest:

For when it dawned—they dropped their arms,

And clustered round the mast;

Sweet sounds rose slowly through their mouths,

And from their bodies passed.

Around, around, flew each sweet sound,

Then darted to the Sun;

Slowly the sounds came back again,

Now mixed, now one by one.

Sometimes a-dropping from the sky

I heard the sky-lark sing;

Sometimes all little birds that are,

How they seemed to fill the sea and air

With their sweet jargoning!

And now ‘twas like all instruments,

Now like a lonely flute;

And now it is an angel’s song,

That makes the Heavens be mute.

It ceased; yet still the sails made on

A pleasant noise till noon,

A noise like of a hidden brook

In the leafy month of June,

That to the sleeping woods all night

Singeth a quiet tune.

Till noon we quietly sailed on,

Yet never a breeze did breathe:

Slowly and smoothly went the ship,

Moved onward from beneath.

Under the keel nine fathom deep,

From the land of mist and snow,

The spirit slid: and it was he

That made the ship to go.

The sails at noon left off their tune,

And the ship stood still also.

The Sun, right up above the mast,

Had fixed her to the ocean:

But in a minute she ‘gan stir,

With a short uneasy motion—

Backwards and forwards half her length

With a short uneasy motion.

Then like a pawing horse let go,

She made a sudden bound:

It flung the blood into my head,

And I fell down in a swound.

How long in that same fit I lay,

I have not to declare;

But ere my living life returned,

I heard and in my soul discerned

Two VOICES in the air.

“Is it he?” quoth one, “Is this the man?

By him who died on cross,

With his cruel bow he laid full low,

The harmless Albatross.

“The spirit who bideth by himself

In the land of mist and snow,

He loved the bird that loved the man

Who shot him with his bow.”

The other was a softer voice,

As soft as honey-dew:

Quoth he, “The man hath penance done,

And penance more will do.”

Part The Sixth

First Voice.

But tell me, tell me! speak again,

Thy soft response renewing—

What makes that ship drive on so fast?

What is the OCEAN doing?

Second Voice.

Still as a slave before his lord,

The OCEAN hath no blast;

His great bright eye most silently

Up to the Moon is cast—

If he may know which way to go;

For she guides him smooth or grim

See, brother, see! how graciously

She looketh down on him.

First Voice.

But why drives on that ship so fast,

Without or wave or wind?

Second Voice.

The air is cut away before,

And closes from behind.

Fly, brother, fly! more high, more high

Or we shall be belated:

For slow and slow that ship will go,

When the Mariner’s trance is abated.

I woke, and we were sailing on

As in a gentle weather:

‘Twas night, calm night, the Moon was high;

The dead men stood together.

All stood together on the deck,

For a charnel-dungeon fitter:

All fixed on me their stony eyes,

That in the Moon did glitter.

The pang, the curse, with which they died,

Had never passed away:

I could not draw my eyes from theirs,

Nor turn them up to pray.

And now this spell was snapt: once more

I viewed the ocean green.

And looked far forth, yet little saw

Of what had else been seen—

Like one that on a lonesome road

Doth walk in fear and dread,

And having once turned round walks on,

And turns no more his head;

Because he knows, a frightful fiend

Doth close behind him tread.

But soon there breathed a wind on me,

Nor sound nor motion made:

Its path was not upon the sea,

In ripple or in shade.

It raised my hair, it fanned my cheek

Like a meadow-gale of spring—

It mingled strangely with my fears,

Yet it felt like a welcoming.

Swiftly, swiftly flew the ship,

Yet she sailed softly too:

Sweetly, sweetly blew the breeze—

On me alone it blew.

Oh! dream of joy! is this indeed

The light-house top I see?

Is this the hill? is this the kirk?

Is this mine own countree!

We drifted o’er the harbour-bar,

And I with sobs did pray—

O let me be awake, my God!

Or let me sleep alway.

The harbour-bay was clear as glass,

So smoothly it was strewn!

And on the bay the moonlight lay,

And the shadow of the moon.

The rock shone bright, the kirk no less,

That stands above the rock:

The moonlight steeped in silentness

The steady weathercock.

And the bay was white with silent light,

Till rising from the same,

Full many shapes, that shadows were,

In crimson colours came.

A little distance from the prow

Those crimson shadows were:

I turned my eyes upon the deck—

Oh, Christ! what saw I there!

Each corse lay flat, lifeless and flat,

And, by the holy rood!

A man all light, a seraph-man,

On every corse there stood.

This seraph band, each waved his hand:

It was a heavenly sight!

They stood as signals to the land,

Each one a lovely light:

This seraph-band, each waved his hand,

No voice did they impart—

No voice; but oh! the silence sank

Like music on my heart.

But soon I heard the dash of oars;

I heard the Pilot’s cheer;

My head was turned perforce away,

And I saw a boat appear.

The Pilot, and the Pilot’s boy,

I heard them coming fast:

Dear Lord in Heaven! it was a joy

The dead men could not blast.

I saw a third—I heard his voice:

It is the Hermit good!

He singeth loud his godly hymns

That he makes in the wood.

He’ll shrieve my soul, he’ll wash away

The Albatross’s blood.

Part The Seventh

This Hermit good lives in that wood

Which slopes down to the sea.

How loudly his sweet voice he rears!

He loves to talk with marineres

That come from a far countree.

He kneels at morn and noon and eve—

He hath a cushion plump:

It is the moss that wholly hides

The rotted old oak-stump.

The skiff-boat neared: I heard them talk,

“Why this is strange, I trow!

Where are those lights so many and fair,

That signal made but now?”

“Strange, by my faith!” the Hermit said—

“And they answered not our cheer!

The planks looked warped! and see those sails,

How thin they are and sere!

I never saw aught like to them,

Unless perchance it were

“Brown skeletons of leaves that lag

My forest-brook along;

When the ivy-tod is heavy with snow,

And the owlet whoops to the wolf below,

That eats the she-wolf’s young.”

“Dear Lord! it hath a fiendish look—

(The Pilot made reply)

I am a-feared”—”Push on, push on!”

Said the Hermit cheerily.

The boat came closer to the ship,

But I nor spake nor stirred;

The boat came close beneath the ship,

And straight a sound was heard.

Under the water it rumbled on,

Still louder and more dread:

It reached the ship, it split the bay;

The ship went down like lead.

Stunned by that loud and dreadful sound,

Which sky and ocean smote,

Like one that hath been seven days drowned

My body lay afloat;

But swift as dreams, myself I found

Within the Pilot’s boat.

Upon the whirl, where sank the ship,

The boat spun round and round;

And all was still, save that the hill

Was telling of the sound.

I moved my lips—the Pilot shrieked

And fell down in a fit;

The holy Hermit raised his eyes,

And prayed where he did sit.

I took the oars: the Pilot’s boy,

Who now doth crazy go,

Laughed loud and long, and all the while

His eyes went to and fro.

“Ha! ha!” quoth he, “full plain I see,

The Devil knows how to row.”

And now, all in my own countree,

I stood on the firm land!

The Hermit stepped forth from the boat,

And scarcely he could stand.

“O shrieve me, shrieve me, holy man!”

The Hermit crossed his brow.

“Say quick,” quoth he, “I bid thee say—

What manner of man art thou?”

Forthwith this frame of mine was wrenched

With a woeful agony,

Which forced me to begin my tale;

And then it left me free.

Since then, at an uncertain hour,

That agony returns;

And till my ghastly tale is told,

This heart within me burns.

I pass, like night, from land to land;

I have strange power of speech;

That moment that his face I see,

I know the man that must hear me:

To him my tale I teach.

What loud uproar bursts from that door!

The wedding-guests are there:

But in the garden-bower the bride

And bride-maids singing are:

And hark the little vesper bell,

Which biddeth me to prayer!

O Wedding-Guest! this soul hath been

Alone on a wide wide sea:

So lonely ‘twas, that God himself

Scarce seemed there to be.

O sweeter than the marriage-feast,

‘Tis sweeter far to me,

To walk together to the kirk

With a goodly company!—

To walk together to the kirk,

And all together pray,

While each to his great Father bends,

Old men, and babes, and loving friends,

And youths and maidens gay!

Farewell, farewell! but this I tell

To thee, thou Wedding-Guest!

He prayeth well, who loveth well

Both man and bird and beast.

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us

He made and loveth all.

The Mariner, whose eye is bright,

Whose beard with age is hoar,

Is gone: and now the Wedding-Guest

Turned from the bridegroom’s door.

He went like one that hath been stunned,

And is of sense forlorn:

A sadder and a wiser man,

He rose the morrow morn.

1.9.6: From Biographia Literaria

1.9.6.1 From Chapter 4

The Lyrical Ballads with the Preface—Mr. Wordsworth’s earlier poems—On fancy and imagination—The investigation of the distinction important to the Fine Arts.

This excellence, which in all Mr. Wordsworth’s writings is more or less predominant, and which constitutes the character of his mind, I no sooner felt, than I sought to understand. Repeated meditations led me first to suspect,—(and a more intimate analysis of the human faculties, their appropriate marks, functions, and effects matured my conjecture into full conviction,)—that Fancy and Imagination were two distinct and widely different faculties, instead of being, according to the general belief, either two names with one meaning, or, at furthest, the lower and higher degree of one and the same power. It is not, I own, easy to conceive a more apposite translation of the Greek phantasia than the Latin imaginatio; but it is equally true that in all societies there exists an instinct of growth, a certain collective, unconscious good sense working progressively to desynonymize (2) those words originally of the same meaning, which the conflux of dialects supplied to the more homogeneous languages, as the Greek and German: and which the same cause, joined with accidents of translation from original works of different countries, occasion in mixed languages like our own. The first and most important point to be proved is, that two conceptions perfectly distinct are confused under one and the same word, and—this done—to appropriate that word exclusively to the one meaning, and the synonyme, should there be one, to the other. But if,—(as will be often the case in the arts and sciences,)—no synonyme exists, we must either invent or borrow a word. In the present instance the appropriation has already begun, and been legitimated in the derivative adjective: Milton had a highly imaginative, Cowley a very fanciful mind. If therefore I should succeed in establishing the actual existence of two faculties generally different, the nomenclature would be at once determined. To the faculty by which I had characterized Milton, we should confine the term ‘imagination;’ while the other would be contra-distinguished as ‘fancy.’ Now were it once fully ascertained, that this division is no less grounded in nature than that of delirium from mania,

or Otway’s

Lutes, laurels, seas of milk, and ships of amber,

from Shakespeare’s

What! have his daughters brought him to this pass?

or from the preceding apostrophe to the elements; the theory of the fine arts, and of poetry in particular, could not but derive some additional and important light. It would in its immediate effects furnish a torch of guidance to the philosophical critic; and ultimately to the poet himself. In energetic minds, truth soon changes by domestication into power; and from directing in the discrimination and appraisal of the product, becomes influencive in the production. To admire on principle, is the only way to imitate without loss of originality.

It has been already hinted, that metaphysics and psychology have long been my hobby-horse. But to have a hobby-horse, and to be vain of it, are so commonly found together, that they pass almost for the same. I trust therefore, that there will be more good humour than contempt, in the smile with which the reader chastises my self-complacency, if I confess myself uncertain, whether the satisfaction from the perception of a truth new to myself may not have been rendered more poignant by the conceit, that it would be equally so to the public. There was a time, certainly, in which I took some little credit to myself, in the belief that I had been the first of my countrymen, who had pointed out the diverse meaning of which the two terms were capable, and analyzed the faculties to which they should be appropriated. Mr. W. Taylor’s recent volume of synonymes I have not yet seen; (3) but his specification of the terms in question has been clearly shown to be both insufficient and erroneous by Mr. Wordsworth in the Preface added to the late collection of his Poems. The explanation which Mr. Wordsworth has himself given, will be found to differ from mine, chiefly, perhaps as our objects are different. It could scarcely indeed happen otherwise, from the advantage I have enjoyed of frequent conversation with him on a subject to which a poem of his own first directed my attention, and my conclusions concerning which he had made more lucid to myself by many happy instances drawn from the operation of natural objects on the mind. But it was Mr. Wordsworth’s purpose to consider the influences of fancy and imagination as they are manifested in poetry, and from the different effects to conclude their diversity in kind; while it is my object to investigate the seminal principle, and then from the kind to deduce the degree. My friend has drawn a masterly sketch of the branches with their poetic fruitage. I wish to add the trunk, and even the roots as far as they lift themselves above ground, and are visible to the naked eye of our common consciousness.

Yet even in this attempt I am aware that I shall be obliged to draw more largely on the reader’s attention, than so immethodical a miscellany as this can authorize; when in such a work (the Ecclesiasical Polity) of such a mind as Hooker’s, the judicious author, though no less admirable for the perspicuity than for the port and dignity of his language,—and though he wrote for men of learning in a learned age,—saw nevertheless occasion to anticipate and guard against “complaints of obscurity,” as often as he was to trace his subject “to the highest well-spring and fountain.” Which, (continues he) “because men are not accustomed to, the pains we take are more needful a great deal, than acceptable; and the matters we handle, seem by reason of newness (till the mind grow better acquainted with them) dark and intricate.” I would gladly therefore spare both myself and others this labour, if I knew how without it to present an intelligible statement of my poetic creed,— not as my opinions, which weigh for nothing, but as deductions from established premises conveyed in such a form, as is calculated either to effect a fundamental conviction, or to receive a fundamental confutation. If I may dare once more adopt the words of Hooker, “they, unto whom we shall seem tedious, are in no wise injured by us, because it is in their own hands to spare that labour, which they are not willing to endure.” Those at least, let me be permitted to add, who have taken so much pains to render me ridiculous for a perversion of taste, and have supported the charge by attributing strange notions to me on no other authority than their own conjectures, owe it to themselves as well as to me not to refuse their attention to my own statement of the theory which I do acknowledge; or shrink from the trouble of examining the grounds on which I rest it, or the arguments which I offer in its justification.

1.9.6.2: From Chapter 13

On the imagination, or esemplastic power

The IMAGINATION, then, I consider either as primary, or secondary. The primary Imagination I hold to be the living power and prime agent of all human perception, and as a repetition in the finite mind of the eternal act of creation in the infinite I AM. The secondary Imagination I consider as an echo of the former, co-existing with the conscious will, yet still as identical with the primary in the kind of its agency, and differing only in degree, and in the mode of its operation. It dissolves, diffuses, dissipates, in order to recreate: or where this process is rendered impossible, yet still at all events it struggles to idealize and to unify. It is essentially vital, even as all objects (as objects) are essentially fixed and dead.

FANCY, on the contrary, has no other counters to play with, but fixities and definites. The fancy is indeed no other than a mode of memory emancipated from the order of time and space; while it is blended with, and modified by that empirical phaenomenon of the will, which we express by the word CHOICE. But equally with the ordinary memory the Fancy must receive all its materials ready made from the law of association.

1.9.6.3 Chapter 14

Occasion of the Lyrical Ballads, and the objects originally proposed—Preface to the second edition—The ensuing controversy, its causes and acrimony— Philosophic definitions of a Poem and Poetry with scholia.

During the first year that Mr. Wordsworth and I were neighbours, our conversations turned frequently on the two cardinal points of poetry, the power of exciting the sympathy of the reader by a faithful adherence to the truth of nature, and the power of giving the interest of novelty by the modifying colours of imagination. The sudden charm, which accidents of light and shade, which moonlight or sunset diffused over a known and familiar landscape, appeared to represent the practicability of combining both. These are the poetry of nature. The thought suggested itself—(to which of us I do not recollect)—that a series of poems might be composed of two sorts. In the one, the incidents and agents were to be, in part at least, supernatural; and the excellence aimed at was to consist in the interesting of the affections by the dramatic truth of such emotions, as would naturally accompany such situations, supposing them real. And real in this sense they have been to every human being who, from whatever source of delusion, has at any time believed himself under supernatural agency. For the second class, subjects were to be chosen from ordinary life; the characters and incidents were to be such as will be found in every village and its vicinity, where there is a meditative and feeling mind to seek after them, or to notice them, when they present themselves.

In this idea originated the plan of the Lyrical Ballads; in which it was agreed, that my endeavours should be directed to persons and characters supernatural, or at least romantic; yet so as to transfer from our inward nature a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith. Mr. Wordsworth, on the other hand, was to propose to himself as his object, to give the charm of novelty to things of every day, and to excite a feeling analogous to the supernatural, by awakening the mind’s attention to the lethargy of custom, and directing it to the loveliness and the wonders of the world before us; an inexhaustible treasure, but for which, in consequence of the film of familiarity and selfish solicitude, we have eyes, yet see not, ears that hear not, and hearts that neither feel nor understand.

With this view I wrote The Ancient Mariner, and was preparing among other poems, The Dark Ladie, and the Christabel, in which I should have more nearly realized my ideal, than I had done in my first attempt. But Mr. Wordsworth’s industry had proved so much more successful, and the number of his poems so much greater, that my compositions, instead of forming a balance, appeared rather an interpolation of heterogeneous matter. Mr. Wordsworth added two or three poems written in his own character, in the impassioned, lofty, and sustained diction, which is characteristic of his genius. In this form the Lyrical Ballads were published; and were presented by him, as an experiment, whether subjects, which from their nature rejected the usual ornaments and extra-colloquial style of poems in general, might not be so managed in the language of ordinary life as to produce the pleasurable interest, which it is the peculiar business of poetry to impart. To the second edition he added a preface of considerable length; in which, notwithstanding some passages of apparently a contrary import, he was understood to contend for the extension of this style to poetry of all kinds, and to reject as vicious and indefensible all phrases and forms of speech that were not included in what he (unfortunately, I think, adopting an equivocal expression) called the language of real life. From this preface, prefixed to poems in which it was impossible to deny the presence of original genius, however mistaken its direction might be deemed, arose the whole long-continued controversy. For from the conjunction of perceived power with supposed heresy I explain the inveteracy and in some instances, I grieve to say, the acrimonious passions, with which the controversy has been conducted by the assailants.

Had Mr. Wordsworth’s poems been the silly, the childish things, which they were for a long time described as being had they been really distinguished from the compositions of other poets merely by meanness of language and inanity of thought; had they indeed contained nothing more than what is found in the parodies and pretended imitations of them; they must have sunk at once, a dead weight, into the slough of oblivion, and have dragged the preface along with them. But year after year increased the number of Mr. Wordsworth’s admirers. They were found too not in the lower classes of the reading public, but chiefly among young men of strong sensibility and meditative minds; and their admiration (inflamed perhaps in some degree by opposition) was distinguished by its intensity, I might almost say, by its religious fervour. These facts, and the intellectual energy of the author, which was more or less consciously felt, where it was outwardly and even boisterously denied, meeting with sentiments of aversion to his opinions, and of alarm at their consequences, produced an eddy of criticism, which would of itself have borne up the poems by the violence with which it whirled them round and round. With many parts of this preface in the sense attributed to them and which the words undoubtedly seem to authorize, I never concurred; but on the contrary objected to them as erroneous in principle, and as contradictory (in appearance at least) both to other parts of the same preface, and to the author’s own practice in the greater part of the poems themselves. Mr. Wordsworth in his recent collection has, I find, degraded this prefatory disquisition to the end of his second volume, to be read or not at the reader’s choice. But he has not, as far as I can discover, announced any change in his poetic creed. At all events, considering it as the source of a controversy, in which I have been honoured more than I deserve by the frequent conjunction of my name with his, I think it expedient to declare once for all, in what points I coincide with the opinions supported in that preface, and in what points I altogether differ. But in order to render myself intelligible I must previously, in as few words as possible, explain my views, first, of a Poem; and secondly, of Poetry itself, in kind, and in essence.

The office of philosophical disquisition consists in just distinction; while it is the privilege of the philosopher to preserve himself constantly aware, that distinction is not division. In order to obtain adequate notions of any truth, we must intellectually separate its distinguishable parts; and this is the technical process of philosophy. But having so done, we must then restore them in our conceptions to the unity, in which they actually co-exist; and this is the result of philosophy. A poem contains the same elements as a prose composition; the difference therefore must consist in a different combination of them, in consequence of a different object being proposed. According to the difference of the object will be the difference of the combination. It is possible, that the object may be merely to facilitate the recollection of any given facts or observations by artificial arrangement; and the composition will be a poem, merely because it is distinguished from prose by metre, or by rhyme, or by both conjointly. In this, the lowest sense, a man might attribute the name of a poem to the well-known enumeration of the days in the several months:

Thirty days hath September,

April, June, and November, etc.

and others of the same class and purpose. And as a particular pleasure is found in anticipating the recurrence of sounds and quantities, all compositions that have this charm super-added, whatever be their contents, may be entitled poems.

So much for the superficial form. A difference of object and contents supplies an additional ground of distinction. The immediate purpose may be the communication of truths; either of truth absolute and demonstrable, as in works of science; or of facts experienced and recorded, as in history. Pleasure, and that of the highest and most permanent kind, may result from the attainment of the end; but it is not itself the immediate end. In other works the communication of pleasure may be the immediate purpose; and though truth, either moral or intellectual, ought to be the ultimate end, yet this will distinguish the character of the author, not the class to which the work belongs. Blest indeed is that state of society, in which the immediate purpose would be baffled by the perversion of the proper ultimate end; in which no charm of diction or imagery could exempt the Bathyllus even of an Anacreon, or the Alexis of Virgil, from disgust and aversion!

But the communication of pleasure may be the immediate object of a work not metrically composed; and that object may have been in a high degree attained, as in novels and romances. Would then the mere superaddition of metre, with or without rhyme, entitle these to the name of poems? The answer is, that nothing can permanently please, which does not contain in itself the reason why it is so, and not otherwise. If metre be superadded, all other parts must be made consonant with it. They must be such, as to justify the perpetual and distinct attention to each part, which an exact correspondent recurrence of accent and sound are calculated to excite. The final definition then, so deduced, may be thus worded. A poem is that species of composition, which is opposed to works of science, by proposing for its immediate object pleasure, not truth; and from all other species—(having this object in common with it)—it is discriminated by proposing to itself such delight from the whole, as is compatible with a distinct gratification from each component part.

Controversy is not seldom excited in consequence of the disputants attaching each a different meaning to the same word; and in few instances has this been more striking, than in disputes concerning the present subject. If a man chooses to call every composition a poem, which is rhyme, or measure, or both, I must leave his opinion uncontroverted. The distinction is at least competent to characterize the writer’s intention. If it were subjoined, that the whole is likewise entertaining or affecting, as a tale, or as a series of interesting reflections; I of course admit this as another fit ingredient of a poem, and an additional merit. But if the definition sought for be that of a legitimate poem, I answer, it must be one, the parts of which mutually support and explain each other; all in their proportion harmonizing with, and supporting the purpose and known influences of metrical arrangement. The philosophic critics of all ages coincide with the ultimate judgment of all countries, in equally denying the praises of a just poem, on the one hand, to a series of striking lines or distiches, each of which, absorbing the whole attention of the reader to itself, becomes disjoined from its context, and forms a separate whole, instead of a harmonizing part; and on the other hand, to an unsustained composition, from which the reader collects rapidly the general result unattracted by the component parts. The reader should be carried forward, not merely or chiefly by the mechanical impulse of curiosity, or by a restless desire to arrive at the final solution; but by the pleasureable activity of mind excited by the attractions of the journey itself. Like the motion of a serpent, which the Egyptians made the emblem of intellectual power; or like the path of sound through the air;—at every step he pauses and half recedes; and from the retrogressive movement collects the force which again carries him onward. Praecipitandus est liber spiritus, says Petronius most happily. The epithet, liber, here balances the preceding verb; and it is not easy to conceive more meaning condensed in fewer words.

But if this should be admitted as a satisfactory character of a poem, we have still to seek for a definition of poetry. The writings of Plato, and Bishop Taylor, and Burnet’s Theoria Sacra of Burnet, furnish undeniable proofs that poetry of the highest kind may exist without metre, and even without the contradistringuishing objects of a poem. The first chapter of Isaiah—(indeed a very large portion of the whole book)—is poetry in the most emphatic sense; yet it would be not less irrational than strange to assert, that pleasure, and not truth was the immediate object of the prophet. In short, whatever specific import we attach to the word poetry, there will be found involved in it, as a necessary consequence, that a poem of any length neither can be, nor ought to be, all poetry. Yet if an harmonious whole is to be produced, the remaining parts must be preserved in keeping with the poetry; and this can be no otherwise effected than by such a studied selection and artificial arrangement, as will partake of one, though not a peculiar property of poetry. And this again can be no other than the property of exciting a more continuous and equal attention than the language of prose aims at, whether colloquial or written.

My own conclusions on the nature of poetry, in the strictest use of the word, have been in part anticipated in some of the remarks on the Fancy and Imagination in the early part of this work. What is poetry?—is so nearly the same question with, what is a poet?—that the answer to the one is involved in the solution of the other. For it is a distinction resulting from the poetic genius itself, which sustains and modifies the images, thoughts, and emotions of the poet’s own mind.

The poet, described in ideal perfection, brings the whole soul of man into activity, with the subordination of its faculties to each other according to their relative worth and dignity. He diffuses a tone and spirit of unity, that blends, and (as it were) fuses, each into each, by that synthetic and magical power, to which I would exclusively appropriate the name of Imagination. This power, first put in action by the will and understanding, and retained under their irremissive, though gentle and unnoticed, control, laxis effertur habenis, reveals “itself in the balance or reconcilement of opposite or discordant” qualities: of sameness, with difference; of the general with the concrete; the idea with the image; the individual with the representative; the sense of novelty and freshness with old and familiar objects; a more than usual state of emotion with more than usual order; judgment ever awake and steady self-possession with enthusiasm and feeling profound or vehement; and while it blends and harmonizes the natural and the artificial, still subordinates art to nature; the manner to the matter; and our admiration of the poet to our sympathy with the poetry. Doubtless, as Sir John Davies observes of the soul—(and his words may with slight alteration be applied, and even more appropriately, to the poetic IMAGINATION)—

Doubtless this could not be, but that she turns

Bodies to spirit by sublimation strange,

As fire converts to fire the things it burns,

As we our food into our nature change.

From their gross matter she abstracts their forms,

And draws a kind of quintessence from things;

Which to her proper nature she transforms

To bear them light on her celestial wings.

Thus does she, when from individual states

She doth abstract the universal kinds;

Which then re-clothed in divers names and fates

Steal access through the senses to our minds.

Finally, GOOD SENSE is the BODY of poetic genius, FANC its DRAPERY, MOTION its LIFE, and IMAGINATION the SOUL that is everywhere, and in each; and forms all into one graceful and intelligent whole.

Notes

1.9.7: Reading and Review Questions

- To what degree, if any, is Coleridge’s poetry artless? What significance, if any, does his poetry give to artlessness, and why?

- How, if at all, do Christian practices of sin, recognition of sin, confession, penance, and redemption undergird Rime of the Ancient Mariner, and why? What does the Ancient Mariner need to recognize as his crime, or sin, and why?

- How does Coleridge’s state of imagination in Dejection: An Ode compare to that of Wordsworth’s in Intimations of Immortality? What concerns both men about the imagination? What power(s) of the imagination, if any, do they recover by the end of their respective poems, and how?

- What, if anything, is radical or revolutionary about Coleridge’s vision of unity among man, nature, and God? Why, for example, does he warn readers at the end of “Kubla Khan” to beware the poet?