3.2: Dialogue 2

- Page ID

- 26958

Michael finds an interesting apartment listing.

Michael: Juu-go-ban wa ikura desu ka. How much is number 15?

15番 ばん は、いくらですか。

Honda : Rokuman-nanasen-en desu. It’s ¥67,000.

六万七千円 ろくまんななせんえん です。

Warukunai desu yo. That’s not bad, you know.

悪 わる くないですよ。

Michael: Motto yasui no wa arimasen nee. There isn’t one that’s cheaper, is there.

もっと安 やす いのはありませんかねえ。

Honda : Chotto muzukashii desu nee. That would be a little difficult, wouldn’t it.

ちょっとむずかしいですねえ。

Vocabulary

juugo じゅうご 十五 fifteen

ban ばん 番 (ordinal) number

juugo-ban じゅうごばん 十五番 number fifteen

ikura いくら how much?

rokuman ろくまん 六万 60,000

nanasen ななせん 七千 7000 en えん 円 yen (currency of Japan)

rokuman-nanasen-en ろくまんななせんえん 六万七千円 ¥67,000

warui わるい 悪い bad

waruku nai わるくない 悪くない not bad

motto もっと more

motto yasui もっとやすい もっと安い cheaper

no の one(s)

muzukashii むずかしい 難しい difficult, hard

+doru どる ドル dollar

+yasashii やさしい easy, kind

Grammar Notes

Numbers and Classifiers (~en, ~doru, ~ban)

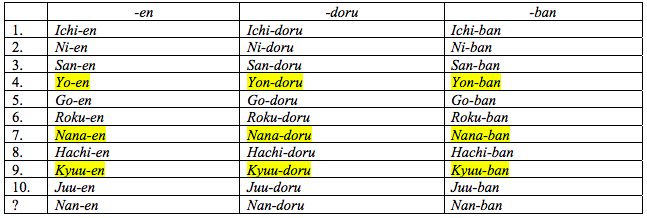

Japanese numbers are listed at the end of this lesson. Note that numbers 4, 7 and 9 have alternating forms: yon, yo and shi for 4, nana and shichi for 7 and kyuu and ku for 9. The form depends on what classifier is combined with the number (See below for classifiers).

In Japanese, numbers with five or more places are counted in groups of four places ( ~man, ~oku, ~chou). On the other hand, in English these numbers are counted by groups of threes places (thousands, millions, billions). So, ten thousand in Japanese has a special name man, and succeeding groups of four places have the names ~oku, and ~chou. Traditionally a comma was inserted every four places (10,000 was written 1,0000).

Note that 10, 100 and 1000 do not require ichi, but 10,000 does. In another words, you need to say ichi only for the last place in each four-place group.

1 ichi 10000 ichi-man

10 juu 100000 juu-man

100 hyaku 1000000 hyaku-man

1000 sen 10000000 sen-man

So, ¥11111111 is sen hyaku juu ichi man sen hyaku juu ichi en. Also note the following sound changes.

For 100’s (hyaku):

h-> b 300 sanbyaku; ?00 nanbyaku (how many hundreds?)

h-> pp 600 roppyaku; 800 happyaku

For 1000’s (sen):

s-> z 3000 sanzen; ?000 nanzen (how many thousands?)

s->ss 8000 hassen

Japanese numbers are usually followed by a classifier, which indicates what is counted or numbered. Use of ‘bare’ numbers is rather limited (counting the number of push-ups, etc.) When counting things in Japanese, numbers are combined with classifiers that are conventionally used for the particular nouns being counted. This is similar to English expressions like “ten sheets of paper” (not ten papers), or “ a loaf of bread” (not a bread.)

Recall that the classifier for clock time is –ji, and grade in school is –nensei. We add three more in this lesson: –en for the Japanese currency, –doru for US currency, and –ban for numbers in order (first, second, etc.) Before –ji, 4, 7, and 9 are respectively yo, shichi, and ku. As shown in the chart below, before –en the number 4 is yo, and the numbers 7 and 9 before –en, doru and –ban are nana, and kyuu.

The classifier -ban is also used for ranking (first place, second place, etc.) Ichi-ban is also used as an adverb to mean ‘most’ or ‘best.’ The pitch accent changes for the adverbial use ( iCHIban -> iCHIBAN)

Ichi-ban jouzu most skillful

Ichi-ban atarashii newest

Ichiban ii daigaku the best college

Pronoun No

Recall that we have the following three noun phrase structures.

1. Adjective + Noun yasui apaato cheap apartment

2. Kono + Noun kono apaato this apartment

3. Noun no Noun watashi no apaato my apartment

It sounds too wordy and unsophisticated if the same noun is repeated unnecessarily. How can we avoid repeating the main noun in these structures when it is already known from the context?

For Structure 1, replace the noun with the pronoun no. -> yasui no inexpensive one

For Structure 2, use kore-sore-are-dore, instead. -> kore this For

Structure 3, just drop it. -> watashi no mine

The pronoun no can replace the noun directly after an adjective, but is usually not used to refer to people. These rules hold when the three structures are combined.

kono atarashii apaato this new apartment -> kono atarashii no

watashi no kono kaban this bag of mine -> watashi no kore

atarashii Amerika no kaisha new American company -> atarashii Amerika no

ka nee 'I wonder'

Some sentence particles can occur in combination. One common combination is ka nee ‘I wonder.’ Ka indicates doubt and nee indicates that the speaker assumes the hearer has the same doubt. In the dialogue above, Michael asks if there are cheaper apartments, assuming Ms. Honda understands his situation. Compare the following:

Motto yasui no wa arimasen ka. Aren't there cheaper ones?

Motto yasui no wa arimasen ka nee. I wonder if there are cheaper ones.

While the first asks for an answer, the second does not demand a response because the speaker assumes that the other person shares the same question. The result is softer. Ka nee is also used as a polite response to a question when the speaker does not know the answer.

Ano hito dare desu ka? Who is that person?

-Dare desu ka nee. I wonder, too.

Dare no kasa desu ka? Whose umbrella is it?

-Dare no desu ka nee. I wonder whose it is, too.