3.2: Charioteers

- Page ID

- 109078

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

In this chapter you will learn about

- Chariot racing, the most popular (by far) sport in Rome and the status of its stars

- How chariot racing operated with a star system far more than gladiatorial combat

- Elite responses to and attacks on chariot racing and charioteers as worthless

FAME AND FANDOM

Chariot racing, unlike gladiatorial combat, was split into four factions, which were the same all over the empire: blue, green, red, and white.. Fans were incredibly devoted to their factions, which were run as private enterprises owned by those of equestrian status until quite late, only being taken over the emperors in the 300s CE. Most races involved all four factions racing against each other either in two or four horse chariots (there could be chariot teams that had up to 10 horses, but those were not used regularly). Sometimes the factions raced pairs of chariots or teamed up against each other, racing two against two. In addition to horses there were more exotic forms of chariot racing, with animals like elephants and camels. Once, when the charioteers refused to race until they were paid more money, one aedile threatened to race dogs; two crumbled but the Blues and Greens held out. Charioteers were the superstars of the ancient sporting world – far more so than gladiators – and some earned immense sums (see, for example, Diocles’ inscription below), although they risked life and limb to do so. We are not sure when the factions started, but our first mention of them is from the 70s BCE when one of the supporters of the Reds threw himself in the funeral pyre of the charioteer Felix:

We find it stated in the Annals, that when Felix, a charioteer of the Reds, was placed on the funeral pile, one of his admirers threw himself upon the pile; a very stupid way to behave. In case, however, that this event might not be attributed to the great excellence of the dead man in his art, and so add to his glory, the other parties all declared that he had been overpowered by the strength of the perfumes.

Pliny the Elder, Encyclopaedia 7.54

Pliny’s words show us how uncomfortable the Romans were with the importance given to men that they considered worthless and of low status, and how unwilling they were to give them even more importance.

LIVE FAST, DIE YOUNG

Charioteers could gain wide celebrity and have long careers, moving from faction to faction over the course of their time racing. However, they started their careers as slaves and could be sold to another faction by their masters, rather than picking and choosing between offers like a modern athlete (we cannot be sure what happened once they obtained freedom). Given the incredibly dangerous nature of chariot racing many of them could also die as slaves, never managing to buy their freedom. One short lived but extremely successful charioteer of the 1st century CE was Scorpus, about whom Martial wrote several poems; the two on his death show the extent of Scorpus’ celebrity.

Poor Gaurus begged Praetor,[1]a man he knew well from a long-standing friendship, for a hundred thousand sesterces, and told him that he only needed that sum to add to his three hundred thousand and qualify him to applaud the emperor as a full equestrian.[2] Praetor replies, “You know, I shall have to give some money to Scorpus and Thallus;[3] and would that I had only a hundred thousand sesterces to give them!” Ah! shame, shame on your ungrateful chests, filled to no good purpose! That which you refuse to an equestrian, Praetor, will you give to a horse?

Martial, Epigrams 5.67

Tragic Victory:[4] shatter your Idumaean palms. Favour, strike your bare chest with wild blows. Honour, change your clothing. Sad Glory, cast your crowned locks as a gift for the unjust funeral pyre. Alas for the shame of it! Scorpus, cheated and cut down in your youth and so quickly yoking the horses of death. Your wheels always hastened the race – but why was the finishing line of your life so close?

Martial, Epigrams 10.50

O Rome, I am Scorpus, the glory of your noisy circus, the object of your applause, your short-lived favourite. The envious Lachesis,[5] when she cut me off in my twenty-seventh year, considered me, judging by the number of my victories, to be an old man.

Martial, Epigrams 10.53

SPECTATORS

Roman moralists worried about the influence of chariot racing on the people of Rome, as it was seen to take them away from important matters. Despite such warnings, many emperors were enthusiastic spectators of the races; some even went so far as to train as charioteers, building their own private racetracks in the city for the purpose; Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, better known as Caligula, built his own on the Vatican Hill, which stood roughly where St Peters now stands.

Caligula also gave many games in the Circus which lasted from early morning until evening; at one time he’d introduce between the races a baiting of panthers and now the manoeuvres of the game called Troy;[6] some, too, of special splendour, in which the Circus race floor was strewn with red and green,[7] while the charioteers were all senators. He also started some games at random, when a few people called for them from the neighbouring balconies,[8] as he was inspecting the outfit of the Circus from the Gelotian house.[9]

Suetonius, Caligula 18.3

The historian Cassius Dio fills out the picture of Caligula’s enthusiasm for the games, which could turn dark for those he did not support:

This was the kind of emperor into whose hands the Romans then fell into. Hence the deeds of Tiberius,[10] though they were felt to have been very harsh, were nevertheless as far superior to those of Gaius [Caligula] as the deeds of Augustus were to those of Tiberius. 2 For Tiberius always kept power in his own hands and used others as agents for carrying out his wishes; whereas Gaius was ruled by the charioteers and gladiators, and was the slave of the actors and others connected with the stage. Indeed, he always kept Apelles, the most famous of the tragic actors of that day, with him even in public.[11] 3 So he by himself and they by themselves did without any restraints all that people like that naturally dare to do when given power. He organized and arranged everything relevant to their art in the most lavish manner at the slightest excuse, and he forced the praetors and the consuls to do the same, so that almost every day some performance of the kind was sure to be given. 4 At first he was but a spectator and listener at these and would take sides for or against various performers like one of the crowd; and one time, when he was vexed with those of opposing tastes, he did not go to the spectacle. But as time went on, he came to imitate, and to contend in many events, 5 driving chariots, fighting as a gladiator, giving exhibitions of pantomimic dancing, and acting in tragedy. So much for how he normally behaved. Once he sent an urgent summons at night to the leading men of the Senate, as if for some important discussion, and then danced before them.[12]

Yet after doing all this he later killed the best and the most famous of these slaves by poisoning. He did the same also with the horses and charioteers of the rival factions; for he was strongly attached to the Greens, which from this colour was called also the Faction of the Leek. Even to‑day the place where he used to practise driving the chariots is called the Gaianum after him.[13] 7 He used to invite one of the horses, which he named Incitatus, to dinner, where he would offer him golden barley and drink his health in wine from golden goblets; he swore by the animal’s life and fortune and even promised to appoint him consul, a promise that he would certainly have carried out if he had lived longer.

Cassius Dio, Roman History 59

Romans who wanted to present themselves as serious and committed to important matters, often prided themselves on being immune to such unRoman activities (though chariot racing was a very old sport in Rome). Pliny the Younger, who was not the most exciting of men, wrote, rather smugly, to his friend Calvisius about how superior he was to the regular, faction man members of the Circus Maximus’ audience:

I have spent the past few days among my papers with the most pleasing serenity you could dream of. You will ask how that can be possible in the middle of Rome? Why, the Ludi Circenses were taking place, a form of entertainment which does not appeal to me at all. The games have no novelty, no variety, nothing, in short, anyone would want to see again. This makes me even more astonished that so many thousands of grown men should be repeatedly possessed with a childish passion to look at galloping horses and men standing upright in their chariots. If, indeed, they were attracted by the swiftness of the horses or the skill of the men, we could account for such passions. But it is actually a scrap of cloth they favour, a scrap of cloth that captivates them. And if during the running the racers were to exchange colours, their supporters would change sides, and instantly abandon the very drivers and horses whom they were just before recognizing from afar, and loudly cheering by name. And that is the level of favour, of weighty influence, that one cheap tunic has with not only the common crowd who are more worthless than the tunics they wear, but with certain important people! When I observe such men so insatiably fond of so silly, so low, so uninteresting, so common an entertainment, I congratulate myself that I am insensible to these pleasures and am glad to devote the leisure of this season, which others throw away upon the most idle employment, to literature. Farewell.

Pliny the Younger, Letters 9.6

FAME AND FORTUNE

Because charioteers could earn a considerable amount of money over their careers, as well as fame, they could afford to set up records of their lives and victories in the same way elites and other wealthy Romans did. This inscription, which commemorates the charioteer Scirtis and his wife, Carisia Nessis, a freedwoman, dates from 13-25 CE and shows the fondness for listing all victories in exhaustive detail that the more detailed honorific inscriptions for charioteers have; however, the sum total of wins is not great and reflects that this was not a good period for spectacles, especially expensive ones like chariot racing.

Scirtis, freedman, charioteer for the Whites.

In the consulship of Lucius Munatius and Gaius Silius,[14] in the four horse chariot 1 victory, 2nd 1 time, 3rd 1 …

In the consulship of Sextus Pomepius and Sextus Appuleius, 1 victory, 2nd 1 time, 3rd 2 times

In the consulship of Drusus Caesar and Gaius Norbanus, 2 victories, was recalled once, 2nd 5 times, 3rd 3 times

In the consulship of Gaius Caelius and Lucius Pomponius, 2 victories, was recalled once, 2nd 8 times, 3rd 6 times

In the 3rd consulship of Titus Caesar and the 2nd of Germanicus Caesar,2nd 7 times, 3rd 12 times

In the consulship of Marcus Silanus and Lucius Norbanus, was recalled once, 2nd 5 times, 3rd 5 times in the consulship of Marcus Valerius and Marcus Marcus Aurelius, 2nd 3 times, 3rd 4 times in the 4th consulship of Titus Caesar and the 2nd of Drusus Caesar, 2nd 2 times, 3rd 5 times

In the consulship of Decimus Haterius Agrippa and Sulpicius 2nd 3, 3rd 4

In the consulship of Gaius Asinius and Gaius Antistius Vetus, was recalled once, 2nd 1 time, 3rd 5 times

In the consulship ofServilius Cornelius Cethegus and Lucius Visellenius 2nd 1 time, 3rd 4 times

In the consulship of Cossus Cornelius Lentulus and Marcus Asinius 3rd 2 times

… Grand total: 7 victories in a four horse chariot, was recalled 4 times, second 39, third 60. He once raced during an official suspension of public business, and twice raced in a six horse chariot. CIL 6.10051

A vastly more successful charioteer was Diocles, who raced from the age of 18 and achieved immense success over the 24 years his career spanned. A monument erected in 146 CE details all of his victories at length:

Gaius Appuleius Diocles, charioteer for the Reds, born in Lusitania, Spain, aged 42 years, 7 months, 23 days. He first drove for the Whites during the consulship of Acilius Aviola and Corellius Pansa [122 CE]. He first won for the same faction during the consulship of Manlius Acilius Glabrio and Gaius Bellicius Torquatus [124 CE]. He first drove for the Greens during the second consulship of Torquatus Asprenatis and the first of Annius Libo [128 CE]. He first won for the Reds during the consulship of Laenatis Pontianus and Antonius Rufino [131 CE]. His wins: drove a four-horse chariot for 24 years. He started 4,257 races, won 1,462, he won the first race of the day 110 times.[15] In races for single four horse chariots he won 1,064 times, and in this he took the largest purse 92 times; he won the 30,000 sesterces prize 32 times (3 of them in a 6 horse chariot), the 40,000 sesterces prize 28 times (twice in a 6 horse chariot), the 50,000 prize 28 times (one in a 6 horse chariot), the 60,000 sesterces prize three times. In races for pairs of four horse chariots he won 347 times; and won 15,000 4 times in a three horse chariot. In races for three chariots he won 51 times. He gained honours 1,000 times He was second 861 times, third 576, fourth with 1,000 sesterces once, and took no prize 1,351 times. He won jointly with a charioteer for the Blues ten times; with one from the White 91, and shared the 20,000 purse twice. His total winnings were 35,863,120 sesterces. He also won 1,000 sesterces in a two-horse chariot, jointly with a White charioteer once and with a Green twice. He won while leading from the gate 815 times, coming from behind 67, after being passed 36, in different ways 42, and at the finishing line 502. He won against the Greens 216 times, against the Blues 205, and against the Whites 81 times. Nine horses had 100 wins with him and one had 200. His notable achievements: In the year when he first won twice driving a four horse chariot, he won at the finishing line twice. The acta say that Avilius Teres was the first in his faction to win 1,011, and he won most often in one year for single chariots, but in that year Diocles won over 100 victories, winning 103 races, 83 of them for single chariots. Increasing his fame he passed Tallus of his faction, who was the first in the Reds to…But Diocles is the most distinguished of the charioteers, since in one year he won 134 races with another charioteer’s lead horse, 118 races for single chariot, which puts him ahead of all the charioteers who compete in the games. It is noted by all, with well-deserved admiration, that in one year with unfamiliar lead horses, with Cotynes and Pompeianus as the inside pair, he won 99 times, winning the 60,000 purse once, the 50,000 four times, 40,000 once, and 30,000 twice. …for the Greens winner 1025 times, Flavius Scorpus, winner 2048 times, and Pompeius Musclosus, winner 3550 times. Those three charioteers won 6,652 times and won the 50,000 purse 28 times, but Diocles, the greatest charioteer ever, won the 50,000 purse 29 times in 1,462 wins. CIL 6.10048

Such monuments testify to the desire of charioteers to post their life histories and successes in the way that the elite did, to appear Roman, even if their status was infamis.

Bibliography and further reading:

Bell, S., 2013. Roman Chariot Racing: Charioteers, Factions, Spectators. In: P. Christesen and D. G. Kyle, ed., A Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity. Oxford: 491-502.

A nice introduction to the topic that doesn’t presuppose that the reader already is familiar with ancient spectacles or chariot racing. Good place to start.

Cameron, Alan. 1976. Circus factions: Blues and greens at Rome and Byzantium. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

Deals mainly with a later period than this anthology, but an amazing read if you want to know hoq the devotion to the factions kept developing until it ruled many aspects of peoples’ lives.

Humphrey, John H. 1986. Roman circuses: Arenas for chariot racing. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

Nelis-Clément, Jocelyne, and Jean-Michel Roddaz. 2008. Le cirque romain et son image. Bordeaux, France: Ausonius.

Even if you can’t read French, the images are amazing.

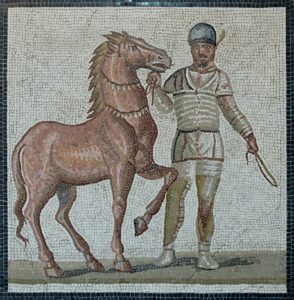

Media Attributions

- Mosaic_white_charioteer_Massimo

- This is not the name of any particular Roman, but is a (high) ranking office in Rome, so stands in for any very wealthy Roman. ↵

- Equestrians had to have 400,000 sesterces in property to qualify for that rank. ↵

- Thallus is not mentioned elsewhere by Martial, although there is an inscription from 90 CE to a charioteer Thallus (ILS 3532). ↵

- Victory, Favour, Honour, and Glory were all Roman gods. Palms were often called Idumaean, because although they could be found in Southern Italy, they were said to be from Idumaea, a region in Judea. ↵

- One of the three Fates and the one responsible for allotting people the years that they would live. ↵

- This, the lusus Troaia, was a complicated set of equestrian manouvers by aristocratic youths. It usually took place on the Campus Martius and sometimes resulted in major injuries. ↵

- To match the colours of the Reds and Greens respectively. ↵

- Of the houses surrounding the Circus Maximus. ↵

- Located on the Palatine Hill. It was originally a private house owned by a wealthy freedman of Augustus, called Gelos, but was incorporated into the imperial palace at some point. ↵

- The previous emperor, who was not well liked. ↵

- The modern cult of celebrity makes this seem innocuous, but in Rome actors were infamis, that is they were not at all respectable company for a senator, let alone an emperor. Not that that really stopped most people. ↵

- Whenever I try and visualize this words fail me. ↵

- Originally, an open racetrack it became a circus and was known as the Circus of Gaius or the Vatican Circus. ↵

- 13 CE; each consulship after that represents a year. ↵

- The Latin says he won from the pompa, that is right after the parade that opened the races. ↵