3.1: Actors and stage performers

- Page ID

- 109077

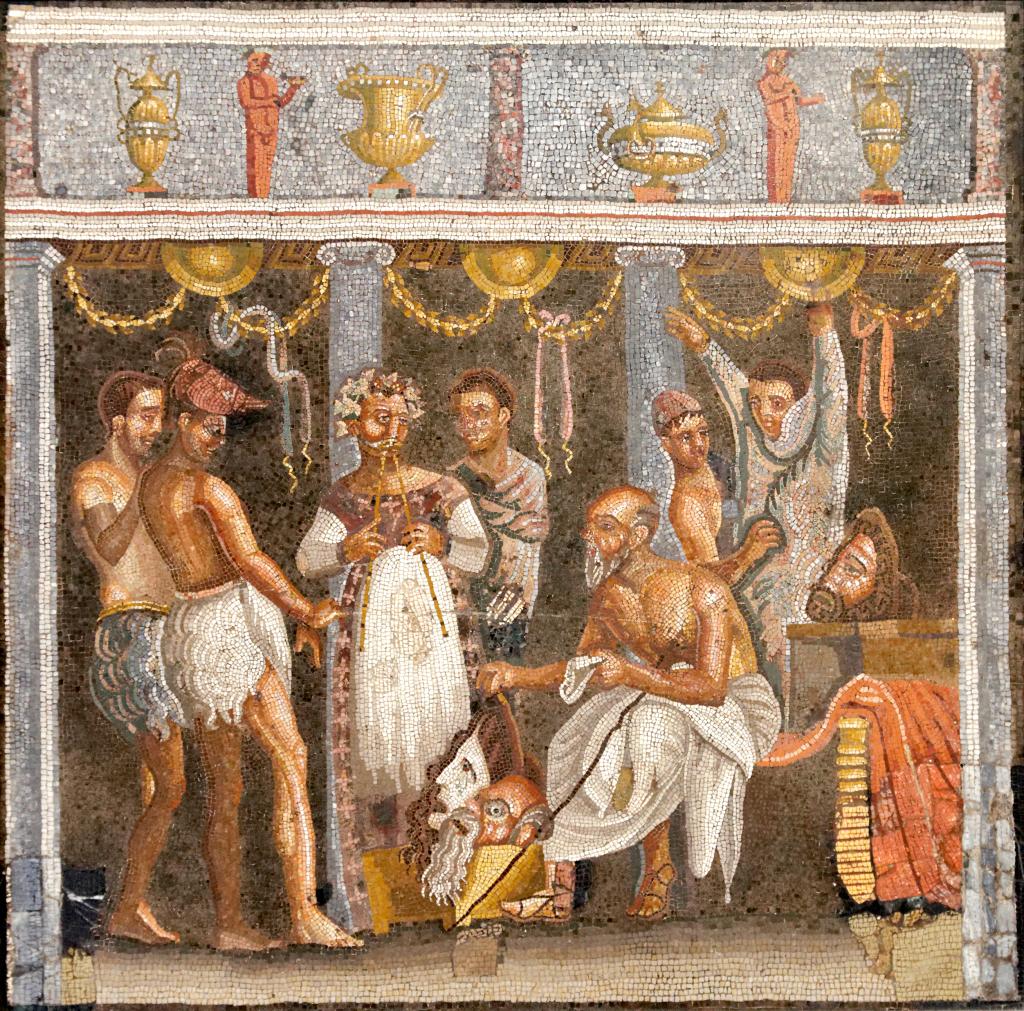

Actors and Stage Performers

Learning Objectives

This section tells you about

- the social and legal situations of most actors

- the types of actors in Rome

- elite perspectives on actors getting ‘beyond their station’ and acting in ways that they did not approve ofpraetor

Like gladiators and charioteers – and all those who were perceived as selling their bodies – actors were infamis (except for those who acted in Atellan farce) and while they might acquire great fame and wealth, had a very low status in the Roman hierarchy. The Emperor Augustus took action against some actors who it was felt were getting above their status.

Augustus was so very strict about curbing the shocking behavoiur of actors, that when he learned that Stephanio, an actor in the fabula togata,[1] was waited on by a matrona with hair cut short to look like a boy, he had him whipped with rods through the three theatres and then banished him. Hylas, a pantomimic actor, was publicly lashed in the atrium of his own house, at the complaint of a praetor, and Pylades[2] was expelled from the city and from Italy as well, because by pointing at a spectator who was hissing at him with his finger he turned all eyes upon him.

Suetonius, Augustus 14

Mime was one of the few areas of drama where women could appear on stage as something other than extras or background (most women’s roles were played by men) and mime actresses had at least one association in Rome, the Sociae Mimae, as we know from an undated inscription from Rome (CIL 6.10109; the same volume has other inscriptions relating to various mime actresses). They also performed across the empire, as can be seen in the following extract from a 2nd century CE novel, the Golden Ass:[3]

The fateful day finally came and I was led to the amphitheatre’s outer wall by an enthusiastic and crowded procession. The entertainment began with actor’s comic mimes, while I enjoyed myself by the gate browsing the rich and juicy grass growing at the entrance, and now and then refreshing my eyes with a glance at the show through the open gate. There were boys and girls in the prime of youth, exceptional for their fresh beauty, splendid costumes, and graceful movements, ready to perform the Pyrrhic[4] dance. They moved in decorous unwavering order, now weaving in and out in a whirling circle, now linking hands in a slanting chain, now in wedges forming a hollow square, now separating into distinct troops. When the trumpet’s final note unwove the knotted complexities of their intricate motion, the curtain was raised, the screens folded back, and the stage setting appeared.

There stood a mountain of wood, built with noble skill to resemble that illustrious Mount Ida that Homer sang of.[5] It was planted with living trees and bushes, and from its summit a stream of water flowed from a fountain made by the designer’s own hand. A handful of goats were cropping the grass and a youth, beautifully dressed in the manner of Paris, as Phrygian shepherd, an Asiatic robe flowing over his shoulders, a gold tiara on his brow, pretended to be tending the flock. Then a shining lad appeared, naked except for a cloak worn on his left shoulder, attracting all gazes with his blond hair, with little gold wings on either side projecting from his curls and a wand, proclaiming him as Mercury. He danced forward bearing in his right hand an apple covered in gold leaf, and offered it to the actor playing Paris. Then, relaying Jupiter’s instructions for the action to follow, he nodded, swiftly and gracefully retraced his steps, and vanished. Next arrived a respectable looking girl dressed as the goddess Juno, a pure white diadem on her brow and a sceptre in her hand.[6] Then on came another you’d have recognised as Minerva, a shining helm crowned with an olive wreath on her head, holding a shield and brandishing a spear as if off to battle.[7] Then another girl made her entrance, a real beauty with an ambrosial complexion, playing Venus, as Venus looked before marriage. Her exquisite naked form was bare except for a piece of silken gauze with which she veiled her sweet charms. An inquisitive little breeze kept blowing this veil aside in wanton playfulness so that it lifted now to show her ripening bud, or now pressed madly against her, clinging tightly, smoothly delineating her voluptuous limbs. The goddess’ very colouring offered interest to the eye, her body the white of heaven from which she came, her veil the cerulean blue of the sea from which she rose.

Each of the girls who played a goddess was accompanied by attendants; Juno by two lads from the acting troop, depicting Castor and Pollux, heads capped with helmets shaped like halves of the egg they came from, topped by stars to signify the Twins, their constellation. To the sound of an Ionian flute piping melodies, the goddess advanced with calm unpretentious steps, and with graceful gestures promised Paris rule over all Asia if he granted her the prize for beauty. The girl whose weapons denoted Minerva was guarded by two boys, depicting Terror and Fear, armour-bearers to the war-goddess, leaping forward with drawn swords. Behind them a piper played a battle tune in the Dorian[8] mode, a deep droning intermingled with shrill screeches, stirring them to energetic dance. Minerva tossed her head, glared threateningly, and informed Paris in swift and abrupt gestures that should he grant her victory in the beauty contest then with her assistance he would be renowned for his bravery and his triumphs in war.

Then came Venus, to the audience’s loud applause, taking her place gracefully at centre-stage, sweetly smiling and ringed by a host of happy little boys, so chubby and milky-white you’d have thought them real cupids flown down from heaven or in from the sea. With little wings and archery sets and all the rest they truly fitted the part, lighting their mistress’ way with glowing torches as if they were off to a wedding feast. Next a crowd of beautiful girls streamed in, the most graceful of Graces, the loveliest of Hours, scattering garlands and loose flowers in tribute to their goddess, paying honour to the queen of all pleasure with the blossoms of spring.

Now flutes of many notes played Lydian tunes in sweet harmony, and as their soft melodies charmed the hearts of the audience, Venus began a gentle dance, with slow hesitant steps and sinuously swaying body and head, advancing with delicate movements to the sweet sound of the flutes. Letting fly passionate or sharp and menacing glances, she often seemed to be dancing by means of her eyelids alone. As soon as she reached the judge, Paris, she promised with transparent gestures, that if he preferred her above the other two goddesses she would grant him a bride of marvellous beauty, the very image of herself. At this the Phrygian youth, gladly handed her the golden apple, in token of yielding her the victory.

Apuleius, The Golden Ass Book 10, (Adapted translation from A.S. Kline)

There were other female performers including dancers (the Romans were extremely fond of dance and it was a far more important theatrical genre to them than to many modern societies). The poet Martial wrote the following on an unnamed dancer from Cadiz:

She quivers so sexily, she makes her so charmingly available, that she would make a masturbator even out of Hippolytus.[9]

Martial, Epigrams 14.203

He also wrote the following, possibly about the same dancer:

Telethusa, skilled in displaying attractive gestures to the sound of her Spanish castanets, and in dancing the beats of Cadiz; Telethusa, capable of exciting the decrepit Pelias, and of moving the husband of Hecuba at the tomb of Hector;[10] Telethusa inflames and tortures her former master. He sold her a slave, he now buys her back a mistress.

Martial, Epigrams 14.204

This link takes you to an inscription for a female performer who died at 14; it gives you some idea of their training and skill. However, like all performers they were frequently slaves (as you can see from above) and had no choice in their performing, and were always vulnerable to assaults and abuse.

Mime: pantomime

Pantomime, however, was focused on star male performers. It was introduced to Rome by the Emperor Augustus’ freedman Pylades in 22 BCE and became immediately popular:

Augustus allowed the praetors who wanted to do so to spend three times as much on the public festivals as the amount granted them from the treasury. Thus, even if some people were annoyed at the strictness of his other regulations,[11] this action and his restoration of one Pylades, a mime, who had been exiled on account of sedition, ensured they remembered them no longer. This is why Pylades is said to have replied very cleverly, when the emperor rebuked him for having quarrelled with Bathyllus, a fellow-artist, and a favourite of Maecenas: “It is to your advantage, Caesar, that the people should devote their spare time to us.”

Cassius Dio, Roman History 54.17

The popularity of mimes gave them the ability to also voice attacks on the emperor and go unscathed at times:

How grossly Tiberius was in the habit of abusing women even of high birth is very clearly shown by the death of a certain Mallonia. When she was brought to his bed and refused most vigorously to submit to his lust, he turned her over to the informers, and even when she was on trial he did not cease to call out and ask her “whether she was sorry”; so that finally she left the court and went home, where she stabbed herself, openly upbraiding the ugly old man for his obscenity. Hence a stigma put upon him at the next plays in an Atellan farce was received with great applause and became a saying, that “the old goat[12] was licking the does.”

Suetonius, Tiberius 45.4

Elite Romans were fans of mime, as much as the ordinary people. However, other Romans were deeply offended at mime and the effect that such performers had on their audience.

Can you find any woman that’s worthy of you under our porticoes? Does any seat at the theatre hold one you could take from there and love with confidence? When sinuous Bathyllus[13] dances his pantomime Leda,[14] Tucia wets herself and Apula cries out as if she were making love with sharp tedious cries. Thymele watches carefullt: naive Thymele learns something.

Juvena,l Satire 6[15] (Translated by A. S. Kline)

However, such criticism was ignored by most, including wealthy Romans who owned mimes and hired them out for huge profits. Some of these also used them in their house for private entertainment – one such was Numidia Quadratilla, a very wealthy lady of the late 1st century CE:

Numidia Quadratilla has died, having almost reached the age of eighty. Up until her last illness she enjoyed uninterrupted good health, and was unusually strong and robust for a woman. She has left a very sensible will, having left two-thirds of her estate to her grandson, and the rest to her grand-daughter. The young lady I know very slightly, but the grandson is one of my closest friends. He is a remarkable young man, and his merit entitles him to the affection of a relation, even where his blood does not. Notwithstanding his remarkable attractiveness he escaped all malicious gossip both as a boy and a youth: he was a husband at twenty-four, and would have been a father if fate had not disappointed his hopes. He lived in close quarters with his luxury-loving grandmother, but was very scrupulous about his own behaviour, although he respected her. She kept a company of pantomimes and was an encourager of this class of people to a degree not appropriate for one of her gender and social status. But Quadratus was never at these entertainments whether she gave them in the theatre or in her own house; nor, indeed, did she require him to be present. I once heard her say, when she was recommending to me the supervision of her grandson’s studies, that it was her custom, in order to pass away some of those unemployed hours with which female life abounds to amuse herself with playing at draughts or watching her pantomimes, but that whenever she engaged in either of those amusements she always sent away her grandson to his studies: she appeared to me to act in this way as much out of reverence for the youth as from affection. I was a good deal surprised, as I am sure you will be too, at what he told me the last time the priestly games were on.[16] As we were coming out of the theatre together, where we had been entertained with a show of these pantomimes, “Do you know,” said he, “to-day is the first time I ever saw my grandmother’s freedman dance?” Such was the grandson’s speech! While a set of men of a far different stamp, in order to do honour to Quadratilla (I am ashamed to call it honour), were running up and down the theatre, pretending to be struck with the utmost admiration and rapture at the performances of those pantomimes and then imitating in musical chant the expression and manner of their lady patroness. But now all the reward they have got, in return for their theatrical performances, is just a few small legacies, which they have the mortification to receive from an heir who was never so much as present at these shows.

Pliny the Younger, Letters 7.24

The popularity of mime and its star system did give immense power to the actors, and although you might be able to expel them for a while no emperor would risk cutting the Romans (who were prone to rioting) off from one of their most loved forms of enterainment. Attempts to curb their power and income often went badly as in the great mime riots of 14/15 and 23 CE, when Tiberius tried to cut their payments.

That year [14 CE] saw a new form of religious ritual with the addition of a new college of Priests of Augustus, which was patterned on the ancient Titian brotherhood founded by Titus Tatius[17] to safeguard the Sabine rites. Twenty-one members were drawn by lot from the leading Roman houses and Tiberius, Drusus, Claudius, and Germanicus were added.[18] The LudiAugustales, celebrated for the first time, were marred by a disturbance caused by the rivalry of the mime actors. Augustus had allowed these theatrical shows to please Maecenas, who was deeply in love with Bathyllus. He himself also had no personal dislike for amusements of this type,[19] and considered it a graceful act to take part in the pleasures of the crowd. Tiberius had other tendencies, but as yet he lacked the courage to force into the ways of austerity a nation which had been indulged for so many years.[20]

Tacitus, Annales 1.54

Another historian, a Greek, adds some more details, which lets us know that this was about pay:

Meanwhile the people rioted, because at the Ludi Augustales one of the actors would not enter the theatre for the regular pay and they did not stop rioting until the tribunes of the plebs convened the senate that very day and begged it to permit them to spend more than the legal amount.

Cassius Dio, Roman History 56.47.2

Then next year saw more riots on a larger scale; it appears Tiberius this time cut the fee for mimes (Suetonius, Tiberius 34.1), while his son Drusus (then around 30) was extremely friendly with them:

While Tiberius was carrying out these measures, Drusus performed the duties pertaining to the consulship equally with his colleague [Tiberius], just as any ordinary citizen might have done; and when he was left heir to someone’s estate, he assisted in carrying out the body.[21] Yet he was so given to violent anger that he hit a distinguished equestrian and for this exploit received the nickname of Castor. 10 And he was becoming so heavy a drinker, that one night, when he was forced to lend aid with the Praetorian Guard to some people whose property was on fire and they called for water, he gave the order: “Serve it to them hot.” He was so friendly with the actors, that this class created a riot and could not be brought to order even by the laws that Tiberius had introduced for regulating them.

Cassius Dio, Roman History 57.14.9-10

These are the laws that are being referred to above:

The disorderliness of the stage, which had become apparent the year before, now broke out on a more serious scale. In addition to casualties among the people, several soldiers and a centurion were killed, and an officer of the Praetorian Guards wounded, in the attempt to repress the insults levelled at the magistracy and the dissension of the crowd. The riot was discussed in the Senate and it was suggested that the praetors should be given the authority to punish actors. Haterius Agrippa, a tribune of the plebs, vetoed this proposal and was attacked in a speech by Asinius Gallus. Tiberius said nothing, allowing the Senate to have this simulacrum of liberty. Still the veto held good, for the deified Augustus had once answered a question by saying that actors were immune from the whip,[22] and it would be blasphemy for Tiberius to now do the opposite of what he had said. They passed a great number of laws to limit the expenditure on entertainments and to curb the extravagance of the fans. The most striking were: that no senator was to enter the houses of pantomime actors; that, if they came out into public, Roman equestrians were not to gather around them, nor were their performances to be followed except in the theatre; while the praetors were to be authorized to punish any disorder among the spectators with exile.

Tacitus, Annales 1.77

As you can see from the above, despite their low legal status is was clear that mimes were being treated like elite Romans in the Senate, who were also gathered around as they went to the Senate, and that Senators were going to their houses instead of – as was the norm – them coming to their houses and showing respect to them.

These laws did not work and in 23 CE (the same year Drusus died) the riots broke out once more:

Next, after various and generally ineffective complaints from the praetors, Tiberius at last brought up the question of the effrontery of the histriones:[23] “They were frequently the instigators of sedition against the state and of depravity in private houses; the old Oscan farce, the trivial delight of the crowd, had come to such a pitch of indecency and power that it needed the authority of the Senate to check it.” The histriones were then expelled from Italy.[24]

Tacitus, Annales 4.14

It was not just the actors who were expelled, but the leaders of their factions, that is their fan clubs, which were very dedicated and willing to take to violence in support of their stars:

He took great pains to prevent disturbances by the people and punished those that occurred very, very severely. When a quarrel in the theatre ended in bloodshed, he banished the leaders of the factions, as well as the actors who were the cause of the trouble – and no entreaties of the people could ever induce him to recall them.

Suetonius, Tiberius 37.2

Bibliography and Further Reading:

The ancient author Lucian is one of the few ancient authors to write about the dance, and his work in it can be found here.

Fernández, Zoa Alonso. 2015. “Docta saltatrix: Body Knowledge, Culture, and Corporeal Discourse in Female Roman Dance.” Phoenix,69: 304-333.

Slater, W. 1994. Pantomime Riots. Classical Antiquity,13: 120-144.

Webb, Ruth. 2008. Demons and Dancers: Performance in Late Antiquity. Cambridge, UK.

- A type of drama where the actors wore Roman, rather than Greek, dress. ↵

- He was a freedman of Augustus and one of those who introduced pantomime to the Romans; he focused on tragic pantomime. He attacked the audience on other occasions: one when he was acting out the madness of Hercules the audience hissed at him for not dancing properly; he threw off his mask and screamed “idiots! I am acting the role of a madman!” His exile was in 18 BCE – he was back within a year. ↵

- The speaker is the hero of the novel who has been turned into a donkey due to an unfortunate incident with magic. ↵

- A type of war dance. ↵

- The reference and the following are to mythical events that preceeded the Trojan War and which are now being staged as a dance. Paris, one of the sons of the King of Troy, was a shepherd on the mountain and was picked to adjudicate a competition between three goddesses: Juno, Minerva, and Venus. He picked Venus because she offered him Helen of Troy.. ↵

- Because she symbolized power and queenship. ↵

- Minerva was a Roman goddess often assimilated to the Greek war goddess, Athena. ↵

- Dorian here is an allusion to the war like people of Sparta, an ancient Greek power that was now run as a bit of tourist destination for Romans and others. ↵

- Hippolytus is a mythical Greek hero who had an almost fanatical commitment to chastity. ↵

- Priam, the elderly king of Troy. ↵

- Augustus pushed through a great deal of moral legislation as emperor. ↵

- Tiberius had retired to the island of Capri,; the Latin for goat is caper, hence the double meaning. ↵

- One of Augustan artists who introduced pantomime to Rome; he appears to have focused on comic pantomime and rather sexy version of myths. ↵

- A pantomime based on the myth of Leda and the swan. ↵

- This is a satire against women in which Juvenal basically accuses them of all the evils that a Roman could imagine. And that was quite a few. ↵

- Games run and put on by members of the priestly colleges, rather than the magistrates. ↵

- A legendary king of the Sabines, who eventually co-ruled that people and the Romans along with Romulus. ↵

- All were members of the imperial family. ↵

- Augustus seems to have been extremely fond of mime, in fact. ↵

- Tacitus really hates Tiberius, so take such comments with a pinch of salt. ↵

- null ↵

- This is not consistent with the story about the mime Stefanio that opens this section. ↵

- This can refer to a wide range of actors, though probably mime actors are intended here. ↵

- Normally they would only be expelled from the city of Rome. ↵