8.6: Poetry in Aristocratic Society

- Page ID

- 135193

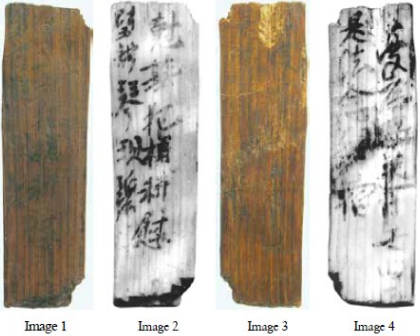

Tang and Hei’an (Chapter 9) aristocrats all learned to write poetry proper to any social occasion from birthdays to journeys to funerals to imperial sacrifices. (This is called “occasional poetry.”) Silla aristocrats may have done the same. A few wooden tablets with poems have survived from Silla. Figure 8.11 shows the two sides of one of the tablets: it is about six inches long, and based on dates given on other tablets excavated from the same pond, it must have been written around 750-800. Scholar Lee SeungJae points out that these tablets were not sharpened so as to be stuck into something; nor did they have v-shaped grooves around the top for tying them onto something; nor did they have holes punched in the tops so that they could be strung together.27 What would you conclude from that?

Lee concludes that the tablet was not meant to last, but was written during a social occasion.

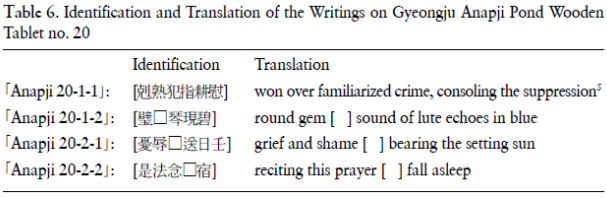

Scholars had to figure out which was side 1, and are still debating exactly which Chinese characters the graphs correspond to, for they are irregular and take years of work to see and read. Lee spends pages going through every character and arguing for his reading of each, giving the images so that the reader can see for herself (134-48). The words represented by □ are now totally illegible. Try turning this into an English poem before you read Lee’s comments.

How did your poem come out?

All across East Asia, elite celebrations include writing what is called “occasional poetry.” Verses had to follow strict rules. They honored the host or person being celebrated, and enabled everyone to show off their literary talent and make catty comments about others. It was a central form of entertainment and social bonding.

Lee points out that the four lines fit with no known verse-form in terms of the line length and rhyme. But there were many forms of verse, and the 5-7-5-7-7 syllable count of Japanese waka may have developed in Silla. Lee speculates that the literary narrator of the poem (whether or not s/he was the actual author) was a Silla general sent to suppress a revolt: Samguk sagi records six revolts between 768 and 780. The tablet was found in an artificial pond that was built inside the palace in the Silla capital, where banquets were often held, so Lee speculates that the occasion of the poem was a banquet held to celebrate this general’s victory.28

Lee writes that lines 1 and 2 lay out the time and place, while lines 3 and 4 show how the speaker is feeling (140). Lee also explains, in terms of grammar, that lines 1 and 2 are in Classical Chinese word order Subject-Verb-Object, while lines 3 and 4 are in Korean-language word order SOV.† With that in mind, try again to make the lines into a sensible English poem. Could the different grammars used relate to content?29

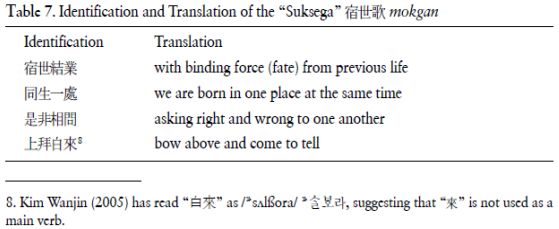

Lee also translated an even earlier wooden tablet, called “Suksega,” from a cemetery of Paekche royalty buried between 538 and 660. Written down around 575-600, it too has mixed word order. Can you turn this into a meaningful poem or piece of prose in English?

These tablets hint at how much we have lost of what people were writing. They have survived only by the merest chance, slipping out of someone’s hand and into a pond, to be covered over with mud for centuries.

By contrast, reams and reams of Tang poetry have survived. An indispensable part of elite life, it was used to make social connections and celebrate public and private events, as well as recording emotions and observations, and serving as a medium of creativity. Elite men also shared poetry and music with courtesans: educated entertainers at the high end of a large prostitution industry centered in Chang’an and Loyang. Out of a culture in which poems were an everyday event, a few great poets emerged: Li Bai, Du Fu, Bai Juyi, Li Shangyin, and others. Many of the great poets also served in office – Du Fu did so during and after the An Lushan rebellion of 755, for instance, so he left many poems about being separated from his family, seeing the country torn apart, and the sufferings of others in a time of civil war. (Song men sometimes dreamed of Du Fu giving them the first two lines of a poem.)30

† This is a fundamental way linguists classify languages. English and Chinese are SVO, Japanese is SOV.