12.2: Economic Changes and Environmental Constraints

- Page ID

- 127026

In the early 1970s, the long era of uninterrupted postwar prosperity came to an abrupt halt. From that point forward, California’s economy faced a series of challenges rooted in overseas competition, deindustrialization and capital flight, and shifts in federal spending priorities. As residents entered this new era of economic uncertainty, they also confronted the environmental costs associated with decades of uncontrolled growth. Air and water pollution, diminishing open space, toxic wastes, and resource shortages eroded the quality of life and generated an unprecedented level of public support for regulatory legislation. In the long run, however, it would prove extremely difficult to reconcile ecological constraints with private economic interests and consumer habits. By the mid-1980s, environmental degradation, while slowed by protective measures, was still proceeding with alarming rapidity.

The Economy

Despite periodic downturns, California’s economy, by conventional measures of growth, expanded during the 1970s and 1980s. In contrast to its industrial competitors in the East and the Midwest, the state benefited from its competitive edge in the high-tech industry and growing trade with the Pacific Rim, Mexico, and Latin America. As a consequence, the California economy enjoyed an overall increase in corporate profits, gross domestic product, per capita income, and job creation. By the late 1980s, the state’s economy outperformed that of most nations, ranking sixth in gross domestic product, seventh in the amount of goods and services produced, and 12th in the value of its international trade.

For large segments of the ever-expanding labor force, however, economic growth did not translate into a higher standard of living. Inflation outpaced wage increases, leading to a decline in real income. Blue-collar jobs in heavy industry increasingly moved overseas or to lower-wage regions of the United States. Many of the newly created jobs were in the service sector, paying lower wages, and affording fewer benefits and opportunities for upward mobility than the industrial jobs that they had replaced. The economic costs of “deindustrialization” were staggering. East Los Angeles, for example, lost 10 of its 12 largest manufacturing industries between 1978 and 1982, at a cost of 50,000 jobs. Fontana, 50 miles to the east, was built around the state’s largest steel mill. In 1983, the plant closed, depriving 6,000 workers of their jobs and completely destroying the city’s industrial base. Oakland and southern Alameda County also felt the impact of deindustrialization and capital flight as businesses closed or relocated where labor and operating costs were lower.

California’s geographic position on the Pacific Rim, however, and higher levels of economic diversification helped cushion the transition to a servicebased economy. By the 1970s, global industrial production shifted from the United States and Europe to developing nations, especially Asian countries. California, situated at the edge of this emerging industrial center, eagerly exploited the economic advantages of foreign trade. By 1984, Pacific Rim nations were buying 78 percent of the state’s exports, including agricultural commodities, aircraft, electronics, and military hardware. In turn, they supplied 85 percent of the state’s imports, usually at a lower cost to consumers than domestic producers. At the same time, Asian financiers invested in California real estate, financial institutions, hotel and convention facilities, and industry. By 1985, one out of every five jobs in the state was linked directly to trade, with countless others dependent on the influx of investment capital.

Like the rest of the nation, however, California was plagued by a growing trade deficit, spending more on imports than it obtained from its exports. In addition, more jobs moved overseas than were created by new partnershipswith Asian investors. Even California’s seemingly invincible electronicsindustry was in constant danger of losing its competitive edge to overseas manufacturers. Nevertheless, the state’s political and business leaders remained convinced that the benefits of Pacific Rim trade would outweigh its short-term disadvantages.

California also had the advantage of a more diverse economic base. Long before most states faced the sudden and traumatic transition to a postindustrial economic order, California had shifted from heavy manufacturing to services. Before World War II, more than half of the state’s work force was employed in the service sector—jobs including social services, government, education, transportation, retail and wholesale trade, real estate, finance, insurance, and utilities. By 1970, almost 70 percent of the work force held service sector jobs, with only 27 percent employed in manufacturing and construction. During the 1970s and 1980s, the service sector continued to expand, accounting for more than three-fourths of all new jobs created in California.

The growth of service sector employment created new job opportunities for many of the state’s residents; however, workers who lost their jobs in heavy industry often lacked the education and skills to obtain higher-level service employment. Instead, they settled for jobs on its lowest rungs: data processing, telemarketing, retail, food service, custodial, customer service, and institutional, home, and child care. Thus, fewer Californians were able to maintain a middle-class lifestyle, and many entered the ranks of the working poor.

Another growth sector of the economy was the high-tech industry. By the late 1950s, Stanford’s research park had attracted a growing number of firms that developed transistor-based components for radios, televisions, calculators, missile guidance systems, and other electronic devices. Stanford professor William Shockley, a pioneer of transistor technology, soon pushed the industry in a new direction. Experiments at Shockley Transistor Company and its spin off, Fairchild Semiconductor, led to the development of the integrated circuit, a silicon-based microprocessor that could transmit electrical signals with greater efficiency and speed, and store huge volumes of information in “memory.” The

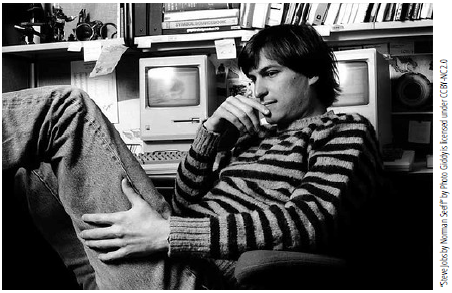

Steve Jobs, chairman of Apple Computer and so-called Computer Kid who launched the personal computing revolution, radiates youthful charm and confidence in this photograph. How did images like this one boost the state's reputation as a place of experimentation, innovation, and openness to alternative work and lifestyles?

silicon chip, introduced in 1959, led to the development of thousands of new products, including mainframe computers.

Relatively large in size and expensive, most early computers were used by government and private industry; however, by the mid-1970s entrepreneurs were developing computers for personal use. From there the industry boomed. The once pastoral Santa Clara Valley became Silicon Valley, home to high-tech millionaires and 20 percent of the nation’s high-tech workers. But while entrepreneurs, engineers, and managers prospered, those who worked on the electronics assembly lines often earned little more than minimum wage. Production workers, mostly immigrant women, were almost exclusively nonunionized, despite their notoriously low wages and dangerous working conditions. Moreover, as housing prices soared, few could afford to live close to their jobs. The industry’s golden image was also tarnished by its growing economic vulnerability. By the mid-1980s, foreign competition eroded sales and profits, and produced a wave of layoffs, salary cuts, plant closings, and “downsizings.” Although the high-tech industry eventually recovered, Californians came to realize that overreliance on a single industry came with a price.

The state’s defense industry, one of its economic mainstays, also had its ups and downs. Dependent on federal contracts, the industry prospered and declined according to Washington’s budget priorities. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, as national defense outlays slumped, California’s aerospace industry was forced to cut employment by 40 percent. From the mid-1970s to 1980, defense expenditures gradually increased, leading to a modest recovery. When Ronald Reagan assumed the presidency in 1981, federal military spending skyrocketed, bringing unprecedented prosperity to private defense contractors, weapons labs, and military bases. In 1985, for example, Lawrence Livermore Lab received about 35 percent of the Department of Energy’s research and development funds, while private industry claimed one-fifth of the nation’s total defense budget. This expansion continued until 1989, when the collapse of the Soviet Union ended the Cold War. By the early 1990s, California’s defense industries, facing massive reductions in federal funding, were forced to lay off hundreds of thousands of workers.

Environmental Activism and Constraints

Along with these new economic challenges, Californians faced environmental limits to growth. Like other Americans, they had long assumed that natural resources were inexhaustible, or that technological innovation would outpace environmental constraints. By the early 1970s, however, a new generation of activists, emerging out of the counterculture and the new Left, sought to redefine America’s relationship to the natural environment by creating a host of eco-friendly institutions: organic farms, food co-ops, natural food stores and restaurants, recycling and ecology centers, and sustainable living demonstration projects like the Berkeley Integral Urban House and the San Diego Center for Appropriate Technology. An alternative press, disseminating publications like the Whole Earth Catalog, provided practical advice on living within environmental limits.

Just as significantly, baby boom activists brought new vigor and militancy to the state’s environmental movement. Traditional preservationist organizations such as the Sierra Club, National Wildlife Federation, Audubon Society, and Wilderness Society attracted thousands of new members and adopted a less compromising, more militant posture toward their opponents. This included aggressive political lobbying and the use of lawsuits and injunctions to advance their agendas.

Preservationists were only one beneficiary of this new ecological consciousness. Friends of the Earth (1969), League of Conservation Voters (1970), and the Earth Island Institute (1981) attracted young activists by emphasizing a full range of environmental concerns along with more traditional preservationist issues. These three organizations, founded in California but national in scope, addressed resource depletion, overflowing landfills, air and water pollution, species extinction, nuclear contamination, despoliation of wetlands and fisheries, the development of open space and agricultural land, waste dumps, and international environmental issues. Like the older organizations, however, they relied on public education, political lobbying, policy analyses and development, and endorsing or criticizing elected officials.

As environmental concern deepened in the late 1970s and early 1980s, many activists adopted the more militant tactics of the ’60s to advance their agenda. In California, organizations like the Abalone Alliance (1977) and Earth First! (1980) engaged in civil disobedience to block the construction of nuclear power plants and the logging of old-growth forests. They also adopted a new philosophical orientation toward nature. Two elements of this philosophy—bioregionalism and ecofeminism—first emerged in California. Bioregionalists argued that humans should think globally, but act locally to protect the integrity of natural ecological communities. As a result of their efforts, wetland and creek restoration projects, greenbelt alliances, agricultural and open space land trusts, and school and community gardens all proliferated during the late 1970s and 1980s. In some cases, bioregionalism even had an impact on local government, leading cities like Berkeley and Santa Monica to adopt eco-friendly policies like comprehensive recycling programs, municipal greenbelts and organic gardens, and bicycle routes.

Inspired by the work of Berkeley scholars Susan Griffin and Carolyn Merchant, ecofeminism charged that patriarchal values and institutions, deeply rooted in Western tradition, denigrated women as well as nature. Like bioregionalists, ecofeminists called for a shift from anthropocentrism to ecological equality—to a society based on cooperation, diversity, conservation, and stability rather than competition, uniformity, exploitation, and progress. Ecofeminism, blending feminism with ecology, gave women the moral authority to claim a leadership role within the contemporary environmental movement.

Although the state’s environmental movement broadened its base and adopted new, more militant strategies and tactics during the ’70s and ’80s, it largely ignored the needs and concerns of economically disadvantaged communities. A majority of organizations attracted a mostly white, middle-class membership and focused on preservation, resource management, and pollution control. In the meantime, impoverished inner cities and rural communities lacked the economic and political clout to demand protection from polluting industries and toxic waste dumping. Even more troubling, many were forced to choose between jobs and environmental quality. By the mid- 1980s, however, poor communities of color began a movement to tackle “environmental racism.” In 1985, Concerned Citizens of South Central Los Angeles, and Mothers of East Los Angeles, representing the city’s largest Latino and African American communities, inspired a broader national movement against illegal dumping, lax enforcement of environmental regulations, and selective siting of toxic waste incinerators and other polluting industries in poor neighborhoods.

Environmental activists only partially succeeded in altering patterns of consumption and resource management—despite their creativity and political clout. Petroleum dependence was a particularly vexing problem. In the early 1970s, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) reduced oil exports to the United States and instituted a series of price increases. The resulting “energy crisis,” which fueled inflation and contributed to a nationwide

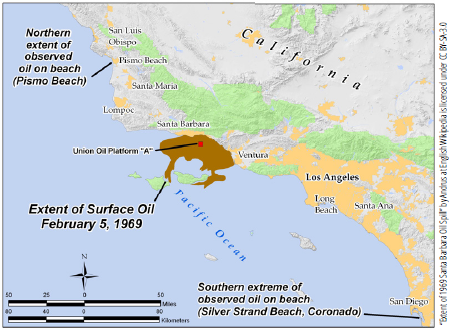

Santa Barbara oil spill. The 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill contaminated hundreds of square miles of ocean and 30 miles of coastline with oil. How might this and other images of the spill have threatened the state's golden reputation as a place where economic growth and great natural beauty coexisted in perfect harmony?

economic recession, was particularly painful for auto-dependent Californians. Several critical industries, including chemicals, plastics, fertilizers, power generation, agriculture, and tourism, also depended on fossil fuels. Offshore oil reserves held some promise of alleviating the crisis, but the disastrous Santa Barbara oil spill of 1969 had produced strong public opposition to coastal drilling. Similarly, the nuclear power industry, which used the crisis to promote atomic energy as a clean, inexhaustible alternative, faced mounting public criticism over safety issues and cost effectiveness. Indeed, by the mid-1980s, antinuclear groups like the Abalone Alliance brought a halt to the industry’s expansion through a combination of lawsuits, civil disobedience protests, and a massive publicity campaign that emphasized the potentially catastrophic impact of accidents, design and siting flaws, and the hazards associated with waste disposal and storage. In Sacramento, the new governor, Jerry Brown, promoted conservation and the development of renewable energy sources as partial solutions to the crisis. Jimmy Carter’s administration in Washington followed suit, calling on Americans to fight inflation and unemployment by reducing their consumption of imported oil.

From the 1970s to the early 1980s, Californians reduced their energy consumption by purchasing fuel-efficient vehicles and appliances, insulating their homes and water heaters, and more carefully monitoring their use of gas and electricity. The California Energy Commission, created in 1975, promoted such measures by setting energy efficiency standards for new household appliances and commercial and residential construction. The government also promoted the development of energy alternatives. In 1977, the state legislature enacted a tax credit program for consumers who purchased solar energy systems. The following year, legislators approved tax incentives for the commercial development of wind energy, giving rise to a series of “wind farms” across the state. Finally, the Public Utilities Commission provided incentives for industries to produce their own electricity through cogeneration.

These measures helped Californians reduce their oil consumption by an astonishing 17 percent between 1979 and 1983; however, this progress was only temporary. When oil prices tumbled in the early 1980s, consumption— particularly in personal transportation—zoomed upward. By 1985, the state was more dependent than ever on imported oil as residents shrugged off their concern and took to the road in a new generation of gas-guzzling vehicles.

At the height of the energy crisis, Californians entered a two-year period of severe drought that necessitated strict water conservation measures and heightened competition over the state’s water resources. Agricultural lobbyists and southern residents revived their campaign for a Peripheral Canal that would increase their annual water supply by 700,000 acre-feet by diverting water directly from the Sacramento River into the existing California Aqueduct. Northern Californians and environmentalists countered that the health of the San Francisco Bay and Delta, dependent on regular infusions of fresh water, would be compromised by the proposed project. The California Water Project, they argued, already diverted too much water, endangering fragile delta, bay, and offshore ecosystems. And agribusiness, the largest water consumer of all, had not done its share to conserve resources or safely dispose of salt-, pesticide-, and fertilizer-laden runoff. Instead of diverting more water from the north, the opposition called for conservation, wastewater reclamation, and curbs on suburban growth.

During the late 1970s, the Brown administration worked to forge a compromise between these competing interests. The result, Senate Bill 200, was passed by the legislature in June of 1980. The bill, while appropriating funds for the canal, also called for constitutional amendments that would strengthen protections for the delta and northcoast rivers. Northern Californians and environmentalists quickly mounted a referendum campaign to overturn the legislation. In June of 1982, state voters approved Proposition 9, defeating the proposed canal by a 62 to 38 percent margin. Growers scored a victory the same year when Congress passed the Reclamation Act, dramatically increasing (from 160 to 960) the number of acres that could be irrigated with federally subsidized water. Moreover, the state’s water wars were far from over. In 1984, Governor George Deukmejian proposed the construction of a scaledback version of the Peripheral Canal. When opponents threatened to force “Duke’s Ditch” onto the 1986 ballot, the year he would be up for reelection, Deukmejian withdrew the proposal. Meanwhile, new battles erupted over existing water resources. In the early 1980s, San Joaquin Valley farmers drained thousands of acre-feet of agricultural wastewater into the Kesterson National Wildlife Refuge. The discharge, contaminated with selenium, created frightening abnormalities in the refuge’s wildlife population. Growers, facing mounting criticism from environmentalists, argued that the practice protected their land from salt buildup. In 1985, the Interior Department settled the dispute when it ordered farmers to halt discharge into Kesterson; however, the growing problem of agricultural soil contamination still defies solution.

In the north, the wildlife at Mono Lake faced a different threat. The City of Los Angeles had diverted water from the area since the 1940s, but in 1970 began to tap the entire flow of the lake’s tributaries. Lake levels dropped precipitously, joining what had once been an island to the shoreline. The California seagull population, which used the island as a breeding ground, was now exposed to predators. Moreover, the increasing salt content of the lake threatened brine shrimp, the major food source of nesting gulls. In 1983, the state supreme court ruled that water rights could be modified or suspended if diversion caused environmental harm. After years of subsequent litigation, Los Angeles was forced to relinquish its water rights, allow the lake to return to a minimally sustainable level, and regulate all future diversions to maintain that level.

Yet other conflicts erupted over California’s scenic and wild rivers. In 1983, environmentalists lost the long battle to prevent impoundment of the free-flowing Stanislaus River behind the New Melones Dam; however, they succeeded in blocking projects along the Tuolumne, Klamath, Eel, Trinity, Smith, and Lower American Rivers. The Sacramento River Delta also received added protection in 1986, when Congress authorized the release of federal water to preserve the region’s fisheries and wildlife habitats.

California’s resources, stretched to the limit by population growth, were also threatened by pollution and poor management. State and federal water quality standards, established in the 1960s and 1970s, and enforced by the Water Resources Control Board and nine regional agencies, reduced the amount of organic contaminants flowing into the state’s waterways. The threat from inorganic substances, however, including heavy metals, PCBs, dioxin, solvents, fuel, pesticides, and fuel additives, increased during the 1970s and 1980s. Illegal dumping and routine violation of bans on certain chemicals prompted voters to pass an anti-toxics initiative in 1986. This law prohibited the discharge of substances that caused cancer and birth defects into water supplies, held the government more accountable for enforcement, and allowed citizens to file lawsuits against violators. The Deukmejian administration held up implementation of the law until the late 1980s by failing to compile a list of regulated toxics.

The problem continued to grow. By the mid-1980s, industry produced more than 26.5 million truckloads of toxic substances annually. In Silicon Valley alone, toxic solvents leaking from storage tanks at more than 120 different sites had contaminated surrounding soil and water. Defense plants, gas stations, oil refineries, and military bases were also common sources of toxic pollution. Cleanup, even with federal support, could take years and cost billions of dollars. And some contaminated sites, including sediment deposits in the San Francisco Bay, can never be restored to health. Bay fish are so heavily contaminated that the public has been cautioned against consuming them.

Federal and state air quality legislation, requiring automobile and oil companies to produce cleaner vehicles and fuel, led to modest improvements in air quality in the state’s older urban centers in the 1970s; however, population growth, concentrated in outlying suburbs, created new smog belts. The San Joaquin and Sacramento Valleys, San Bernardino, Orange, East Contra Costa, and San Diego Counties, and the Los Angeles suburbs regularly exceeded federal air quality standards. As smog blew east, it damaged vegetation in Sequoia National Park and the San Bernardino Mountains. Even the Tahoe Basin, suffering from overdevelopment and traffic congestion, faced a growing air pollution problem.

In 1977, the federal government amended the Clean Air Act to require smog inspection programs for states that routinely violated federal air quality standards. After the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) threatened to withhold funds for highway and sewage treatment projects, California finally adopted a sufficiently rigorous vehicle inspection program. The law, adopted in 1982, required that automobiles pass a smog test every two years. If owners refused to comply, the vehicle’s registration would lapse.

Public transportation, the state’s long-term solution to its air quality problems, took a step forward in the 1970s. The Bay Area Rapid Transit System, which carried its first passengers in 1972, provided a clean, efficient transportation alternative for East Bay and San Francisco residents. The system, expanded during the 1980s and 1990s, also provided a model for other communities, including San Diego, San José, Sacramento, and most recently, Los Angeles. Still, most Californians preferred private transportation and increasingly rejected smaller, more fuel-efficient cars in favor of sport-utility vehicles that are not held to the same emissions standards as automobiles.

Growth control measures sponsored by citizens and municipal governments have also met with mixed results. By the mid-1980s, at least 25 cities and counties passed measures that limited or attached conditions to new construction. But rural areas, eager for the benefits of an expanding tax base, were less willing to limit development. As housing costs increased in established communities, home buyers sought more affordable alternatives in rural areas. To the north, burgeoning suburbs gobbled up fertile farmland in Tracy, Gilroy, Pleasant Hill, Fairfield, Vacaville, Napa, and Santa Rosa. To the south, development pressed into the far reaches of San Diego, Riverside, Los Angeles, and Ventura Counties.

The loss of agricultural land was particularly troubling. In 1965, the state legislature passed the California Agricultural Land Conservation Act to preserve this vital resource. As suburbs spread into rural areas, land values and property taxes increased. Farmers who resisted the temptation to sell to developers faced increasing tax assessments. If farmers signed a 10-year contract agreeing to keep their land in agricultural production, the Land Conservation Act guaranteed that local governments would assess their property at the lower, agricultural level, rather than at subdivided value. Local governments, however, wishing to encourage development, frequently allowed farm owners to sell before their contracts had expired. When the courts demanded stricter compliance, developers successfully lobbied for new escape clauses to the Land Conservation Act. Still, as of 2007, more than 16 million acres of agricultural land were protected from suburban development under the bill.

Environmentalists’ efforts to preserve open space and wilderness areas were also mixed. In 1972, state voters approved Proposition 20, a ballot measure that created a temporary Coastal Commission to regulate development and preserve public access to the shoreline. After vigorous lobbying from conservationists, the legislature voted to create a permanent commission in 1976. With the authority to grant or deny development permits, the commission had jurisdiction over the state’s coastline from 1000 yards inland to three miles offshore. During the Brown administration, the commission rejected or called for modification of thousands of development proposals. Deukmejian, more sympathetic to developers, cut the agency’s budget and staff and appointed like-minded commissioners who approved several large hotel and residential projects. The power of the commission was further eroded by a series of budgetary and jurisdictional limits pushed through by pro-development lobbyists.

The Tahoe Regional Planning Agency (TRPA), established by the U.S. Congress in 1969 and jointly managed by California and Nevada, represented another governmental effort to regulate growth and halt environmental degradation. Throughout the 1970s, the agency, heavily influenced by developers, did little to advance its own mandate. Construction of casinos, resorts, and housing continued, placing severe strain on the basin’s sewage system,roads, air quality, and already limited water supply. Under growing pressure from the federal government and various conservation groups, the TRPA finally adopted more stringent environmental protection standards and a new regional plan.

The TRPA’s 1984 plan, a compromise between Nevada’s pro-development forces and more conservation-minded Californians, allowed for construction of 600 housing units annually over the next three years, with a case-by-case assessment of environmentally sensitive lots. The League to Save Lake Tahoe and California’s attorney general immediately filed legal suits against the agency, charging that the plan violated earlier regional protection compacts. In 1985, the federal court of appeals agreed, suspending the plan and halting all new development in the region. Forced back to the drawing board, the TRPA issued a new plan in 1987 that limited construction to 300 homes annually, and commercial development to 400,000 square feet over the next decade. Amendments also established an environmental ranking system for residential lots and restricted construction in ecologically sensitive areas such as stream zones. Federal and state legislation, authorizing the use of public funds to purchase environmentally sensitive sites, complemented the TRPA’s efforts to restore Tahoe’s water quality and wildlife habitat. Critics, however, argued that these measures were too little, too late. Sadly, the basin’s continuing decline appears to support their contention.

Preservationists’ efforts to extend California’s park and wilderness areas were more successful. Created in 1972, the Golden Gate National Recreation Area and the San Francisco Bay Wildlife Refuge placed thousands of acres of fragile shoreline, marshland, and tidal areas under protection. In 1978, Congress created the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, but the Reagan administration held up federal funds to purchase open space from private owners until the mid-1980s. In 1984, Congress designated 1.8 million acres of federally owned land in the state as wilderness or scenic preserves. Two years later, U.S. Senator Allan Cranston introduced the California Desert Protection Act. Passed by Congress in 1994, the act classified 7.5 million acres of public desert land as protected wilderness and set aside an additional 1.4 million acres as the East Mojave Preserve. Local and state parkland also increased during the 1970s and 1980s, but Proposition 13 forced reductions in maintenance and necessitated increases in user fees.