12: Era of Limits and New Opportunities- 1970–1990

- Page ID

- 127024

Main Topics

- The Legacy of the ’60s

- Economic Changes and Environmental Constraints

- Politics in the Era of Limits

- Summary

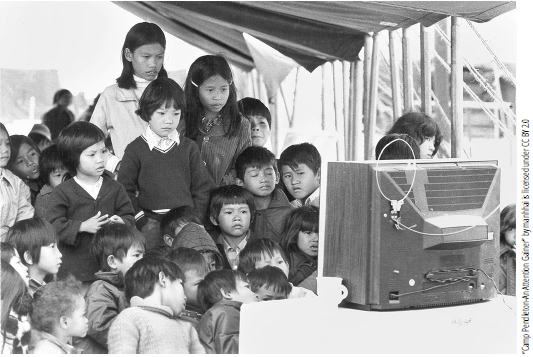

Jacqueline Nguyen, the daughter of a South Vietnamese army major, was born in 1965 just as the U.S. was escalating its involvement in the war. Ten years later, as the South Vietnamese Government fell to Ho Chi Minh’s forces, her father drew on his connections to U.S. military officials to spirit Jacqueline and her siblings to safety on one of the last evacuation planes to leave South Vietnam. Had they remained they would have paid dearly for their father’s loyalty to the losing side. The Nguyens, including five children all under the age of eleven, spent their first several months of “freedom” living in an army tent alongside hundreds of other refugees at Camp Pendleton.

After settling in the La Crescenta-Montrose area of Los Angeles, the family faced new challenges. Major and Mrs. Nguyen worked two to three menial jobs at a time, often with the help of their children, to amass the savings to start their own business. By the time Jacqueline started high school, her parents had purchased a North Hollywood doughnut shop which, like many other immigrant-run businesses, depended upon family labor. Even while attending Occidental College, where she earned a degree in English and comparative literature in 1987, Jacqueline continued to help out between classes and on weekends.

Inspired by her family’s struggle to negotiate the complexities of immigration and small business law, Jacqueline then went on to obtain a doctorate in jurisprudence from UCLA in 1991. Following four years at a private firm, she was appointed Assistant U.S. Attorney in the Central District of California where she supervised fraud prosecutions and rose to the position of Deputy Chief of the General Crimes section. In 2002 Governor Gray Davis, taking note of her work ethic and integrity, appointed her to a Los Angeles County Superior Court judgeship. Becoming the first Vietnamese American woman ever appointed to that position, she quickly built a reputation for fairness and restraint. Impressed with her record, President Obama nominated her in 2009 to a seat on the U.S. District Court for the Central Division—a nomination confirmed by the Senate. Then, in 2012, Jacqueline was nominated and confirmed for a seat on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, becoming the first Asian American to serve as a federal appellate judge.

The Nguyens’ journey was followed by a much larger exodus from Southeast Asia. Although religious and charitable organizations across the U.S. assisted the federal government in resettling wave after wave of destitute boat people, California—with its warm climate, plentiful jobs, and established Asian communities—was the destination of choice. By 1995 an estimated 335,000 refugees had moved to the state, giving California the highest refugee density in the world, and increasing the size and diversity of its Asian population. Although Jacqueline’s meteoric ascent from a refugee child at Camp Pendleton to a federal judge was exceptional, her parents’ story was more typical. The Nguyens, like other immigrants to the state, worked hard to establish a small measure of economic security, and to maintain cultural and family ties. Indeed, following her appointment as Assistant U.S. attorney, Jacqueline continued helping out at the family doughnut shop on weekends—a contribution that signified her unflagging loyalty and gratitude toward her parents.

Whether or not Jacqueline realized it, her family’s experience was an outgrowth of American foreign policy during the

This photograph shows Vietnamese refugee children at Camp Pendleton. What does this image suggest about their ability to adjust to a new life in California? What barriers might they face in their effort to assimilarte?

’60s—a foreign policy that gave rise to a contentious anti-war movement and reshaped national and state politics. But Vietnamese immigration was only one legacy of the ’60s. New forms of activism, growing out of earlier social movements, flourished during the 1970s and early 1980s, and bolstered California’s reputation as a center of experiment and change. As the Nguyens adapted to their new surroundings, they, like other Californians, entered a shifting economic environment. Throughout the ’70s and ’80s, the state’s economy became increasingly tied to the booming trans-Pacific, or Pacific Rim, trade. Although Asian countries provided new markets for California’s products, their cheaper exports damaged other industries and contributed to a growing trade deficit.

Even more significantly, the state’s economy shifted away from heavy industry to service sector employment. Manufacturing jobs, the most heavily unionized in the

state, moved overseas or to lower-wage regions of the United States, while service sector employment accounted for more than three-fourths of all new job growth during the same period. Many Californians, with the education and training to move into higher-wage service employment, benefited from this shift. Others, including new immigrants, were forced into low-paying, largely nonunion service jobs that afforded less in terms of security, benefits, and opportunities for advancement than those in heavy industry.

As these economic shifts unfolded, Californians facedunprecedented limits to growth. The state’s resource base,undermined by decades of economic and demographic expansion, appeared more fragile than ever. Muted by the upheavals of the ’60s, concern resurfaced in often contentious efforts to protect air and water quality, open space, and wilderness areas. During this period of economic change and environmental constraints, a Democratic governor, the son of the great liberal reformer, Pat Brown, entered office. Thirtyseven- year-old Edmund “Jerry” Brown Jr., promising to bring a “new spirit” to Sacramento, defied categorization as a liberal or conservative. He supported the rights of farm workers, opposed the death penalty, and appointed more women and minorities to state office than any of his predecessors. He was also a staunch advocate of environmental protection, resource conservation, and the development of renewable energy sources and sustainable technology. But in fiscal matters, Brown was conservative, asserting that “we are going to cut, squeeze, and trim until we reduce the cost of government.” His refusal to live in the governor’s mansion or use the state limousine and airplane underscored his personal commitment to the “era of limits” philosophy.

By 1982, Brown’s popularity had plummeted. A national economic recession and Proposition 13, a property-tax reduction initiative passed by voters in the late 1970s, plunged local and state governments into fiscal crisis. Economic woes prompted worried residents to elect a Republican governor, George Deukmejian. By the mid-1980s, the national and state economy recovered, quelling any lingering concerns that Jerry Brown’s cautionary message about learning to live within limits might actually have had substance.

Questions to Consider

- How were the social and political movements described in this chapter connected to those of the ’60s? Provide specific examples of the connections.

- To what extent did California’s minority groups make significant progress during the ’70s and ’80s?

- How did the economy change during the “era of limits,” and what were the costs associated with its transformation?

- What were the similarities and differences between the Brown and Deukmejian administrations? Can either be easily categorized as liberal or conservative?