12.1: The Legacy of the ’60s

- Page ID

- 127025

During the 1970s and 1980s, women, people with disabilities, and gays and lesbians launched new movements for social change. Their quest for equal rights and recognition, inspired by the activists of the ’60s, bolstered the state’s reputation for diversity and tolerance and ensured that California remained in the forefront of social and cultural change for decades to come. Simultaneously, the state’s minority population edged closer to attaining majority status and reaped concrete benefits from their earlier struggles. Affirmative hiring and admissions policies, which increased employment and educational opportunities, led to the expansion of the middle class. Most significantly, fair housing and employment legislation afforded some protection against more overt forms of racial discrimination. During the 1970s and 1980s, ethnic minorities sought to consolidate these gains through political action, while simultaneously grappling with a new set of challenges.

Feminism

California’s feminist movement, mirroring national trends, took two directions during the “era of limits.” Liberal feminists, primarily white, middle-class professionals, worked through existing political channels to address issues like wage equity, reproductive rights, child care, and sex discrimination in government, higher education, and the professions. Radical feminists, younger members of the “protest generation,” used more militant tactics to challenge discrimination and alter the cultural values and practices that reinforced women’s inequality.

Liberal feminists responded to the lack of political support for gender equity by founding local National Organization for Women (NOW) chapters and joining national efforts to secure passage of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). In 1972, California became one of the first states to ratify the amendment, but the battle was far from over. By the 1982 congressional deadline, only 35 of the 38 states needed to ensure passage had ratified the ERA.

During the long and ultimately unsuccessful struggle for the ERA, NOW chapters pursued a broader feminist agenda. In 1972, its activists created a statewide organization in California to coordinate the activities of individual chapters and lobby for legislative action. Over the next several years, the neworganization, located in Sacramento, sponsored assembly and senate bills that addressed inequities in the insurance industry, guaranteed stiffer penalties for repeat sex offenders, and protected the privacy of rape victims. NOW, joined by the California Abortion and Reproductive Rights League (1978), also lobbied for access to abortion and birth control.

During the 1980s, NOW and other liberal feminist organizations supported comparable-worth legislation. The number of women in California’s labor force had steadily increased during the 20th century, and by 1970, a majority of women worked for wages; however, most were forced into gender-specific jobs that paid, on the average, only 60 cents for every dollar earned by male workers.Comparable worth, a concept that promoted equal pay for comparable—but not

necessarily identical—jobs, was viewed as a solution to these wage disparities. The legislature approved the use of comparable-worth criteria in setting salaries for state employees in 1981; however, Governor George Deukmejian, who opposed government regulation of private industry, vetoed several other bills that would have extended the practice beyond state employment. As late as 1985, a government task force reported that the state’s labor market was still segregated by sex, with little change in wage differentials between men and women.

California’s women also lagged behind men in holding elected and appointed office. In response, organizations like the California Women’s Political Caucus (1973) and the California Elected Women’s Association for Education and Research (1974) encouraged women to run for office, lobbied for greater representation in appointed positions, and promoted public education and research on women and the political process. By the mid-1970s, their efforts had produced modest results. Jerry Brown, elected governor in 1974, appointed more than 1,500 women to various boards and commissions— more than any previous administration. Women also made gains in the legislature, increasing their representation from six in 1976 to 17 in 1986. All but four, however, served in the assembly, while the state senate and the congressional delegation remained almost entirely male dominated.

Political gains were even more impressive on the local level. In 1978, following Mayor George Moscone’s assassination, Dianne Feinstein was chosen by fellow members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors to finish his term. In 1979, she won the mayoral contest in her own right, becoming the first woman elected to that post. Subsequently, women were elected as mayors of San Diego, Berkeley, Sacramento, and San José, and to a host of city council and county supervisor offices.

In the meantime, younger, radical feminists argued that “mainstreaming” was not enough. The entire society—its religious and moral beliefs, language, literature, art, media, economy, educational system, and political institutions— undervalued and denigrated women. Throughout the state, radical women established small discussion or consciousness-raising groups to share common concerns and come up with strategies for change. Having used direct action to protest racial inequality and the war in Vietnam, many decided to use the same tactics against institutions that they felt degraded women: beauty pageants, the advertising and fashion industries, male-only clubs and professional associations, and the mainstream media.

Similarly, radical feminists followed the countercultural strategy of building alternative institutions: battered women’s shelters, rape crisis centers, health clinics, child care cooperatives, bookstores, cultural centers, art galleries, print and publishing collectives, recording and film studios, theater troupes, and urban and rural communes. Within professional associations, women created caucuses to promote feminist research and the hiring and promotion of women. At colleges and universities, feminist students and faculty launched women’s studies programs. For example, the women’s studies program at San Diego State University, the first in the nation, was established in 1970 by women who had earlier participated in a campus-based consciousness-raising group.

The joint efforts of liberal and radical feminists moved California closer to gender equity, but serious problems remained. Occupational segregation and wage disparities contributed to the “feminization” of poverty in California and the nation as a whole. The women’s movement, attracting mostly white, educated, middle-class feminists, was often slow to address such concerns. Women of color also felt isolated by a movement that emphasized sexism and tended to ignore the impact of racism. In response, African American, Asian American, and Latina feminists often broke away and formed their own organizations, such as Black Women Organized for Action, Asian American Women United, and Mujeres en Marcha.

Disability Rights

The disability rights movement, patterned after the civil rights and ethnic power struggles of the ’60s, was founded by a small group of students on the U.C. Berkeley campus. Between 1962 and 1969, the university housed severely disabled students in Cowell Hospital, the campus health center. For the first time, these young people experienced a sense of community, but also faced barriers to full participation in campus and community life—barriers that limited their access to public places, employment, social services, and recreation opportunities. According to one of the students, Phil Draper, “we wanted to be able to control our own destinies— like the philosophies that propelled the civil rights and women’s movements.”

In 1970, the Berkeley activists, who called themselves the Rolling Quads, formed the Disabled Students’ Program on the U.C. campus. A year later, they established the Center for Independent Living (CIL) in the city of Berkeley “to give people with disabilities the will and determination to move out of hospitals and institutions,” and fully participate in the life of their communities. Over the next several years, Berkeley’s CIL coordinated independent living arrangements for its clients and lobbied for increased community access for the disabled. After extensive pressure from the CIL, for example, the Berkeley City Council allocated funds for curb ramps. Activists then lobbied for improved access to buildings, workplaces, recreation facilities, and public transportation.

By the mid-1970s, the disability rights and CIL movements had spread across the nation, and activists focused their efforts on lobbying for federal legislationthat advanced their access agenda. In 1973, the Rehabilitation Act was signed into law over President Nixon’s veto. Section 504 of the act prohibitedany program or agency receiving federal funds from discriminating againsthandicapped individuals solely on the basis of their disabilities. This was the first time in history that the federal government acknowledged that the exclusion of people with disabilities was a form of discrimination.

The Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) was given the task of drafting guidelines for Section 504’s enforcement; however, by 1977, HEW still had not drafted regulations that addressed architectural and communications barriers to access, and reasonable accommodations for people with disabilities. In response, disability rights activists staged sit-ins at HEW offices across the nation. The San Francisco sit-in, lasting 28 days, marked the longest occupation of a federal building in U.S. history. The demonstrations, combined with a lawsuit, letter-writing campaign, and congressional hearings, prompted HEW to act. On May 4, 1977, Section 504 regulations were issued, creating a precedent for the much broader anti-discriminatory protections later provided by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

During the 1980s, California activists joined the national effort to defend and broaden HEW regulations. Working primarily through the legal system, activists convinced the Supreme Court that Section 504 prohibited employment discrimination and covered people with AIDS and other communicable illnesses. They also obtained federal legislation that allowed the disabled to sue states for violations of Section 504. By 1988, the federal government was ready to introduce a more comprehensive version of the Rehabilitation Act—one that would prohibit all forms of discrimination against people with disabilities, even within organizations and businesses that operated without federal funds. In 1990, the ADA became law, extending to people with disabilities the same protections that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 gave to women and minorities. From its beginnings at Cowell Hospital at U.C. Berkeley, the disability rights movement had become a political force on the local, state, and national levels.

Gay Pride

Inspired by the militancy of the ’60s, gay and lesbian activists created a host of new organizations to combat discrimination and foster “gay pride.” Like radical feminists and disability rights activists, many used direct action to attack homophobic attitudes and institutions. In 1970, for example, gay liberation groups stormed the American Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting in San Francisco to protest the profession’s characterization of homosexuality as a mental disorder. This and similar protests across the nation prompted the APA in 1973 to delete homosexuality from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Like radical feminists, gay liberationists also created alternative institutions and celebrations. Annual gay pride marches in Los Angeles and San Francisco, beginning in 1970, drew ever larger crowds, as did the Gay Games and film festivals. Gay and lesbian community centers, clinics, youth shelters, coffeehouses, restaurants, theaters, sororities, fraternities, choral groups, athletic leagues, and theater companies flourished alongside older gay institutions, adding greater variation and richness to community life.

As these institutions took root, the state became a mecca for those seeking a less-closeted lifestyle. Existing gay and lesbian enclaves, like Venice and West Hollywood, expanded. New communities, like San Diego’s Hillcrest neighborhood, sprang to life. And in San Francisco, older gay enclaves in the Tenderloin, the South of Market area, and North Beach shifted uptown to the Castro District. In San Francisco alone, the gay population almost doubled between 1972 and 1978, growing from 90,000 to more than 150,000.

Growth translated into political power. In 1977, Harvey Milk, a Castro District camera shop owner and community activist, became the first openly gay member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Others soon followed, culminating in the “Lavender Sweep” that brought 11 gays and two lesbians into city office in 1990. Change was even more dramatic in West Hollywood, where, in 1984, voters elected a lesbian mayor and a gay and lesbian majority to the city council. Moreover, by the mid-1980s, several cities had included sexual orientation in their nondiscrimination ordinances, banned discrimination against people with AIDS, and acknowledged the validity of domestic partnerships. Such gains, however, were accompanied by a strong, conservative backlash.

The first challenge came in 1977, when state congressman John Briggs sponsored a ballot initiative that would have required school districts “to fire or refuse to hire … any teacher, counselor, or aide, or administrator in the public school system … who advocates, solicits, imposes, encourages, or promotes private or public homosexual activity … that is likely to come to the attention of studentsor parents.” Gay and lesbian activists, working through organizations like the Bay Area Committee Against the Briggs Initiative and the Committee Against the Briggs Initiative, Los Angeles, convinced voters to reject the measure. Gay rights advocates soon faced another challenge, however.

On November 27, 1978, Dan White, a former police officer and member of the Board of Supervisors, murdered San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone. White, who had recently resigned from the board over a series of disagreements with more liberal members, had a change of heart about leaving his post. Moscone, however, was unwilling to reinstate him. Feeling betrayed and defeated by his liberal opponents, White marched into city hall and took his revenge with a gun. Although subject to the death penalty for assassinating public officials, White was only convicted of manslaughter, a charge that carried a sentence of seven years and eight months. The jury, from which gay and lesbian panelists had been excluded, agreed with psychiatrists who testified that White suffered “diminished capacity” from consuming too much junk food—the so-called Twinkie defense.

Following the verdict on May 21, 1979, thousands of protestors converged on city hall, smashing windows and setting police cars on fire. Later that night, violence spread to the Castro as angry residents engaged in street battles with what they perceived to be an invading army of police officers. At the end of the “White Night” riots, property damage exceeded $1 million, and hundreds had been injured. Just a few months later, another tragedy unfolded.

In 1980, a new disease came to the attention of the Centers for Disease Control. Soon identified as Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), it spread rapidly through California’s gay male communities and eventually to the general population through blood transfusions, intravenous drug use, and unprotected sex. As the death toll mounted, gay and lesbian activists reacted by creating hospices, food banks, counseling and testing services, shelters, and home care networks. They also rallied to demand increased funding for research, testing, treatment, and prevention. At the same time, the AIDS epidemic gave anti-gay conservatives new ammunition in their moral crusade against homosexuality. Proposition 64, placed on the California ballot in 1986, called for the quarantine of people with AIDS. Another ballot measure, sponsored by Southern California U.S. Representative William Dannemyer in 1988, would have required doctors and clinics to report HIV-positive clients to state authorities. Voters, rejecting attempts to label AIDS a highly contagious “gay disease,” defeated both measures. In the meantime, gay and lesbian activists became even more militant. New organizations, like the AIDS Action Coalition (1987) and ACT-UP (1988), used civil disobedience to counter their conservative critics, demand more funding for treatment and research, and attack the pharmaceutical industry for withholding promising drugs and overcharging consumers.

As older activistsmet the challenges of the AIDS crisis, a new generation began to broaden the scope of the gay liberation movement. Moving beyond the heterosexual/ homosexual paradigm, they created organizations that embraced a wide range of marginalized sexual groups that had often been ignored or excluded bygay and lesbian organizations, including bisexual, transgender, and questioning individuals. Queer Nation, representing this new spirit, identified itself as “an informal, multicultural, direct action group committed to the recognition, preservation, expansion, and celebration of queer culture in all its diversity.”

Multiethnic Political Gains

For California’s African American population, the 1970s and 1980s brought a higher level of political representation. In 1970, Wilson Riles was elected as the first black superintendent of public instruction. The same year, Marcus Foster became superintendent of the Oakland public schools, the first African American to head a district of that size. Ronald Dellums, elected to the Berkeley City Council in 1967, took a seat in the U.S. Congress in 1970, joining Augustus Hawkins, who had served his Los Angeles district since 1962. Two years later, Yvonne Braithwaite Burke, a former state assemblywoman, also won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, raising to three the number of black Californians in Congress. In 1973, Los Angeles City Councilman Thomas Bradley became the city’s first African American mayor. Bradley not only served an unprecedented five terms in this office, but also won the Democratic nomination for governor in 1982 and 1986. In 1974, state senator Mervyn Dymally took office as lieutenant governor and later joined the U.S. Congress. By 1980, black Californians were also well represented in the state legislature, with two senators and six assembly members. Assembly speaker Willie Brown would later become mayor of San Francisco, and assemblywoman Maxine Waters, representing Los Angeles, would join the U.S. Congress.

The state’s Hispanic population grew dramatically during the 1970s and 1980s, exceeding 5.7 million by 1985. Constituting nearly 22 percent of the total population by the mid-1980s, Hispanics were California’s largest and fastest-growing minority group. Worsening economic conditions in Mexico, combined with an increase in high-tech manufacturing and service sector employment, contributed to some of this growth; however, large numbers of Central Americans and Chileans, fleeing U.S.-sanctioned political repression and violence, also sought refuge in California. As a consequence, the Hispanic population, concentrated primarily in Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay area, became more diverse. Rapid growth and diversity, in turn, presented challenges to organizations that had long struggled to foster political unity.

In urban areas, middle-class-oriented organizations like LULAC and the GI Forum, which lost membership to more militant groups during the ’60s, recovered in the 1970s as strong advocates of political unity, civil rights legislation, and electoral participation. New organizations, such as United Neighborhood Organization (1975) and Communities Organized for Public Services (1974), followed in the footsteps of the Community Service Organization (CSO) by organizing poor and working-class residents to demand political power and better services for their communities. For these and other organizations, the primary challenge was how to unify and awaken the “sleeping giant”—the Latino electorate.

During the 1970s, the most striking gains came in the form of political appointments. Governor Jerry Brown, assuming office in 1975, appointed a record number of Hispanics to state agencies and the judiciary, including

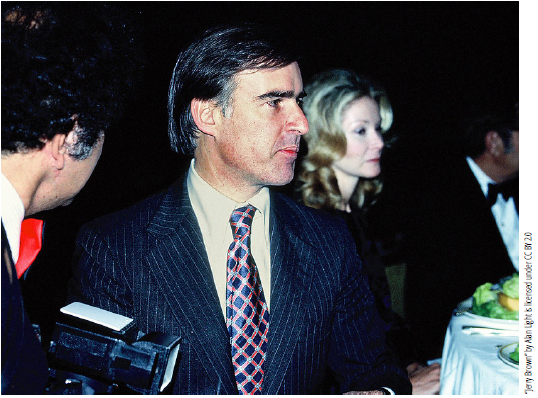

How does this image of Governor Jerry Brown contrast with that of Ronald Reagan? Does Brown project the same level of authority, or is his persona more apt to appeal to the increasingly powerful baby boom constituency of the mid-1970s and early 1980s?

Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare Mario Obledo. Only a small number of Hispanics held elected office on the local and state levels, despite the fact that the number of eligible voters had dramatically increased. But this was about to change. By the 1980s, the growing influx of undocumented workers, coupled with economic recession, precipitated an anti-immigrant backlash. The Simpson-Mazzolli Immigration Reform and Control Act, passed by Congress in 1986, increased penalties for hiring undocumented workers and heightened security at the U.S.-Mexico border. The same year, voters approved an amendment to the state constitution establishing that “English is the official language of the State of California,” and directing legislators and government officials to “take all steps necessary to ensure that the role of English as the common language of the state is preserved and enhanced.” These measures galvanized the Hispanic electorate and led to increased representation in local, state, and national office. The Democratic Party, which took the strongest position in defense of immigrant rights, was the primary beneficiary of this political “awakening.”

Within the state’s Asian population, Japanese and Chinese Americans made the most striking progress in the political arena. Japanese American activists won a major moral victory in 1980, when Congress agreed to establish the U.S. Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. In 1988, the federal government adopted the commission’s recommendation to awardreparation payments of $20,000 to each surviving internee, and to issue a formal apology for wartime exclusion and detention. Although Congress failed to appropriate the necessary funds until 1989, and the first payments were not made until 1991, most Japanese Americans felt at least partially vindicated. Significantly, Norman Mineta, one of the state’s first Japanese Americans elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, announced the government’s decision. In 1976, the year Mineta was initially elected to his post, California voters sent a second Japanese American, Robert Matsui, to Congress, and S. I. Hayakawa to the U.S. Senate. Hayakawa began his controversial political career during the ’60s when, as president of San Francisco State University, he took a hard line against student protestors. After his single term in the Senate, he returned to California and spearheaded the campaign for the 1986 “English Only” ballot initiative.

The state’s Chinese American residents also made some political progress during the 1970s and 1980s. In 1974, March Fong Eu, elected as secretary of state, became the first Asian American to hold statewide office in California. In 1994, soon after she finished her fourth and final term, her son, Matthew Fong, was elected state treasurer. Chinese Americans also gained representation on the municipal level, holding five elected offices in San Francisco by 1980, and one in Los Angeles by 1985. Reflecting the growing Chinese presence in Monterey Park by the 1980s, voters elected Lily Lee as that city’s mayor. In 1974, the state’s Chinese Americans won a major legal victory for public school children with limited English language skills. In Lau v. Nichols, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the failure of schools to meet the linguistic needs of children constituted unequal treatment. Two years later, the state legislature mandated bilingual education in California’s schools.

The activism of the ’60s, including the occupation of Alcatraz Island, reinvigorated the Native American struggle for political visibility and power. In 1983, 17 terminated tribes were restored to their previous status after winning a class action suit, Hardwick v. United States. Others were restoredthrough action initiated by California Indian Legal Services; however, the federal government was slow to help these tribes regain their land base and reestablish their tribal governments. During the 1970s, the Yuroks fought to protect their fishing rights along the Klamath River, and the Achumawis took legal action against Pacific Gas & Electric to reclaim land in northeastern California. In Santa Barbara, Indians occupied a spiritually significant site to prevent construction of an oil tanker terminal. Others, having lost their land and tribal identity, reunified and sought formal recognition from the federal government. For example, the Tolowas of Del Norte County, driven to the brink of extinction in the 19th century by disease and white violence, gradually recovered. In the mid-1980s, they applied for tribal status—a status that promised federal funds for education and health care, and the legal standing to assert their land rights. Other groups, however, could ill afford the long and costly process of establishing common ancestral ties among surviving tribal members.

Ethnicity and Economics

In the economic arena, the state’s African American population experienced both gains and persistent barriers to advancement during the 1970s and 1980s. Affirmative hiring policies and fair employment legislation led to the growth of the black middle class. Entrepreneurship also increased, aided in part by minority contract programs. By the 1980s, California had more blackowned businesses than any other state in the nation, supporting thousands of workers with a payroll of $217 million. At the same time, stronger enforcement of fair housing legislation allowed more prosperous African Americans to move out of the inner city. As a consequence, the older black enclaves of Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Oakland lost some of their economic diversity. In some cases, middle-class flight also altered the ethnic composition of neighborhoods. Watts, for example, went from being a predominantly black enclave to one that is now mostly Asian and Hispanic.

Economic mobility, however, was offset by an increase in black poverty. During the postwar period, inner cities had steadily lost jobs to the suburbs. In the 1970s and 1980s, heavy industry, whether in the urban core or in outlying areas, began to leave the state altogether. Without blue-collar jobs, traditionally a source of upward mobility for those with less education and training, thousands slipped into poverty. State and national cuts in social spending, including Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), compounded the plight of California’s most disadvantaged families. By 1980, nearly three-fourths of all black families lived in poverty. Black workers were twice as likely as whites to be unemployed, and the jobless rate for black youths stood at 40 percent—where it had been just before the Watts riot. Even with the expansion of the black middle class, the average annual income of African American families was only 60 percent of the white average.

Barriers to equal education were part of the problem. Inner-city schools much larger population of disadvantaged youngsters. Recognizing that housing discrimination and income disparities between blacks and whites had contributed to de facto school segregation, many municipalities adopted school integration plans as early as the 1960s; however, Los Angeles, containing the state’s largest school district, had long ignored the fact that 90 percent of its black children attended predominantly black schools. In 1970, after the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed a lawsuit against the district, the state’s supreme court judge, Alfred Gitelson, ordered its officials to initiate an integration plan. In 1978, after losing several appeals, the district finally implemented a mandatory busing plan for its students; however, in 1979 California voters approved a constitutional amendment that limited mandatory busing to cases of legal or intentional segregation. As a consequence of this decision, Los Angeles and other cities abandoned mandatory busing. By this time, many affluent parents—most of them white—had simply removed their children from public schools, or relocated to suburban districts. With or without busing, California’s public schools would remain highly segregated by race and class.

Affirmative college admission programs, another attempt to ensure educational equity, also came under attack shortly after they were implemented. Beginning in 1969, the U.C. Davis medical school reserved 16 out of 100 annual admission slots for minority students. In 1973 and again in 1974, Allan Bakke was turned down for admission. He concluded that Davis rejected him because he was white, and that affirmative action constituted a form of reverse discrimination. After the state supreme court upheld his position, the university appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1978, the justices ruled five to four in favor of Bakke; however, their decision fell short of a blanket condemnation of affirmative action. Such programs, they maintained, were constitutional as long as race was not the only consideration in evaluating an application. For the time being, racial criteria could still be used to increase the diversity of the student population and ensure equal access to higher education.

For Latinos, economic progress was also mixed with challenges. Throughout the 1970s, agricultural workers continued to benefit from the protections offered by the United Farm Workers. After its successful table grape boycott in the late ’60s, the union moved on to organize the state’s lettuce workers. This brought renewed conflict with the Teamsters’ Union. Claiming to represent field workers in the Salinas Valley, the Teamsters signed contracts with several large lettuce growers that provided few benefits for farm labor. Resenting the UFW’s challenge to what they perceived as their jurisdiction, the Teamsters, with growers’ support, mounted a campaign of violence and intimidation against their rival union. The UFW responded by launching a lettuce boycott and lobbying for state legislation that would create an Agricultural Labor Relations Board to supervise union elections and recognize only “one industrial bargaining unit per farm.” The bill, also allowing legalized strikes and secondary boycotts, passed in 1975. The state gave farm workers the legal right to choose a bargaining agent and made a commitment to guaranteeing that elections were noncoerced and fair. Moreover, the law mandated that only the union receiving the majority of votes be allowed to represent the workers on any given farm.

A weakness of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act was that it failed to grant organizers the right to enter farms to speak with workers. Growers could legally block the entry of UFW members while allowing free access to the Teamsters. The Labor Relations Board also lacked the funding necessary to follow up on the many violations of the act, particularly election fraud. Cesar Chavez decided to appeal directly to California voters by launching an initiative campaign. Proposition 14, which appeared on the November 1976 ballot, would have given union organizers free access to the state’s farms and provided adequate funding for the Labor Relations Board. Growers, using deceptive scare tactics similar to those used to overturn the Rumford Fair Housing Act, convinced voters that the initiative threatened

the property rights of all citizens. The measure failed, and the UFW was forced to devote scarce resources to more labor-intensive efforts to recruit new members.

The Agricultural Labor Relations Act was also weakened when Governor George Deukmejian, who took office in 1983, undermined the regulatory function of its board by stacking it with anti-labor members and staff. The growing number of undocumented workers, jurisdictional disputes with rival unions, and a costly new grape boycott further diluted the strength of the organization and undercut its efforts to recruit new members.

Over the next two decades, the UFW took on new battles: the abolition of the short-handled hoe, protecting workers from excessive exposure to pesticides, preventing growers from using undocumented labor to break strikes, and supporting the rights of immigrant workers. The union’s campaign against the short-handled hoe—a tool that crippled thousands of workers—was successful. The other issues, along with the loss of contracts to competing unions and the impact of mechanization on the agricultural labor force, remain on the UFW agenda. With Chavez’s death on April 23, 1993, the union suffered a tremendous loss—a loss compounded by financial problems stemming from a series of lawsuits filed by growers against the union.

In the meantime, a majority of Hispanic workers were employed in nonagricultural sectors of the economy, particularly in low-wage service and high-tech assembly occupations. These sectors, although expanding during the 1970s and 1980s, were largely nonunion. Organized labor, focusing its resources on preserving jobs and membership in heavy industry, was only beginning to reassess its role in the new economy. It would be another decade before service workers, like some janitors and home care providers, organized and enjoyed the benefits of union representation.

California’s Asian American population continued to grow throughout the 1970s and 1980s as immigrants from Hong Kong, Taiwan, Korea, and the Philippines benefited from the 1965 abolition of the national-origins quota system. After the fall of Saigon in 1975, the state also received increasing numbers of Southeast Asian refugees. By 1985, about 750,000 Vietnamese, Laotians, Hmong, and Cambodians had resettled in the United States, with roughly 40 percent choosing California as their final destination. Southeast Asians, admitted under a refugee provision in the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, arrived with special needs. A majority came with few resources, poor English language skills, little understanding of American culture, and a history of emotional and physical trauma.

By 1985, an estimated 350,000 refugees had resettled in California. Under the Refugee Act of 1980, the federal government agreed to provide 36 months of financial support to help newcomers achieve economic selfsufficiency. A year later, the Reagan administration reduced support to 18 months, and decreased funding for refugee assistance programs. As a consequence, state agencies and a growing number of refugee self-help organizations were forced to bear an increasing share of the resettlement burden. The outcome, however, was not entirely negative. Mutual aid organizations, which were given priority in obtaining the remaining federal resettlement funds, were operated by members of the refugee community. Understanding the barriers to assimilation and economic independence, they were able to provide services in a more culturally sensitive manner than state and federal agencies. Moreover, mutual aid societies provided a nucleus for emerging refugee communities and helped foster the development of internal leadership.

While Southeast Asians put down roots, Chinese and Japanese Americans made strides in education and income. The state’s Japanese American residents achieved the most unambiguous measure of success, surpassing the white population in education, representation in professional occupations, life expectancy, family income, and individual earnings. Although Chinese Americans also surpassed whites in high school graduation rates, college attendance, and median family income, their community remained bifurcated. A high proportion had obtained advanced degrees and professional employment, but many lacked the language skills, education, and occupational training to move beyond low-wage service and manufacturing jobs. The experience of Filipino and Korean immigrants also challenged the model minority stereotype. By 1980, Korean Americans were 50 percent more likely than whites to be self-employed or working for a family-owned business. A majority of their businesses, however, were small, requiring the unpaid labor of more than one family member to survive. In addition, Korean entrepreneurship was often the only acceptable substitute for well-educated professionals who faced language and accreditation barriers, and discrimination in their chosen fields.

Filipinos, who displaced Chinese residents as California’s largest Asian group in 1980, also found that their education and training did not guarantee professional employment. Consequently, the number entering the United States on professional visas declined from 27 percent of all Filipino immigrants in the early 1970s to two percent in 1981. Nor was educational success an Asian American universal. In 1980 through 1981, one-quarter of the state’s Filipino high school students, mostly second-generation, failed to graduate. This percentage, far in excess of the 11 percent dropout rate for all Asian Americans, more closely corresponded to the 31 percent average for blacks, and the 35 percent average for Latinos. Finally, while Koreans and Filipinos enjoyed higher median family incomes than whites, they averaged more wage earners per family. When earnings were calculated on a per-person rather than family basis, both groups earned less than whites, even given their higher levels of educational attainment.

Economically, California Indians remained the most disadvantaged of the state’s ethnic groups. During the 1980s, several tribes introduced bingo on their reservations, raising much-needed revenue from outside patrons. These enterprises, exempt from legal prohibitions against gaming, paved the way for the casino gambling initiatives of the late 1990s, which, while controversial, hold the promise of greater economic autonomy for California’s Indian tribes.

Cultural Advances

Throughout the state, each of these groups made striking contributions in the cultural arena. California’s African American population enjoyed greater cultural visibility during the ’70s and ’80s. Hollywood, responding to criticism from black actors, audiences, filmmakers, and civil rights groups, began to offer more diverse, dramatic portrayals of African American life. Independent filmmakers, benefiting from the cultural awareness that grew out of the social movements of the ’60s, reached a wider audience. Marlon Riggs, for example, produced award-winning documentaries on racial stereotypes and black gay identity that aired on public television stations across the nation. Newly established ethnic studies programs and academic associations promoted scholarship on African American history, psychology, politics, health, education, and culture. A new generation of black writers, including poet June Jordan, novelist Ishmael Reed, and social critic Angela Davis, increasingly captured the attention of a multicultural readership. Black dance and theater companies provided new venues for performing artists. And the music world embraced talent as diverse as Tower of Power and the innovative conductor of the Oakland Symphony, Calvin Simmons.

For Latinos, the cultural renaissance launched during the ’60s continued into the 1980s. Luis Valdez, founder of El Teatro Campesino, produced a number of plays that reached audiences beyond the farm worker movement. Zoot Suit, Bandido, Los Corridos, and I Don’t Have to Show You No Stinkin’ Badges, for example, highlighted Chicano history, folk culture, and political resistance. Muralists continued to decorate public spaces with colorful depictions of historical figures and events, and to commemorate contemporary struggles against immigration restrictions, freeway construction, and urban “renewal” projects. Cultural centers and museums housed and promoted the arts. Mexican American studies programs produced a new generation of scholars, writers, and artists. And barrios, housing a growing number of businesses and cultural institutions, Hispanicized surrounding communities. San Francisco’s Mission District, for example, attracted a growing number of outside visitors to its cultural events, restaurants, and markets by the late 1980s. Finally, despite “English Only” legislation, the state maintained and strengthened its commitment to bilingual education and issued an increasing number of publications, including election materials, in the Spanish language.

In the cultural arena, Asian American scholars, writers, and artists continued to explore their cultural heritage and challenge negative ethnic stereotypes. Maxine Hong Kingston, Jeanne Wakatsuki, Janice Mirikatni, and Yoshiko Uchida enriched and enlivened the state’s literary canon. Judy Narita’s one-woman show, exploring stereotypes of Asian American women, won the Los Angeles Drama Critics’ Circle Award, Drama-Logue Award, and the Association of Asian/Pacific Artists’ “Jimmie” Award. Films, including Farewell to Manzanar, “Gam Saan Haak” (Guests of Gold Mountain), Sewing Woman, The Fall of the I Hotel, Bean Sprouts, and China, Land of My Father, depicted the diversity, strength, and resourcefulness of Asian Americans to broader audiences.

A new generation of Indian activists focused on preserving and reclaiming tribal culture and history. Scholar/writers like Paula Gunn Allen, Greg Sarris, and Gerald Vizenor have devoted their careers to chronicling, interpreting, and establishing the contemporary relevance of traditional myths and cultural practices. Individual tribes, like the Cupeno and Cahuilla, alarmed over the disappearance of their cultural traditions, established cultural centers and museums to preserve their language, history, and tribal artifacts. In 1976, the California Native Heritage Commission was established to help Indians preserve culturally significant sites and artifacts. The Indian Repatriation Act, passed by Congress in 1990, gave tribes across the nation the right to recover cultural artifacts and ancestral remains that had long been held in public museums and institutions. It also prohibited individuals from desecrating or appropriating Indian remains and cultural property.