6.2: New Social Patterns

- Page ID

- 126970

California was becoming ever more urban—by 1900, more than 40 percent of Californians lived in its 10 largest cities. Urban growth was just one of the social and cultural changes that were also occurring elsewhere in the United States, including the emergence of new educational institutions, changes in the status of women, and large-scale immigration.

Education

During the Gilded Age, great changes occurred in education, including the expansion of higher education. Religious organizations created California’s earliest colleges. Methodists received the state’s first college charter, in 1851, for California Wesleyan College, later the University of the Pacific. In 1851, Joseph Alemany, first Catholic bishop of California, gave the Santa Clara mission to Jesuit priests for a college, and Santa Clara College (later Santa Clara University) obtained its charter in 1855. Southern California lagged in creating colleges. Los Angeles Methodists planned the University of Southern California in the 1870s, but the university opened in 1880 only because of a gift of land by three donors—one Protestant, one Catholic, and one Jewish. Presbyterians founded Occidental College in 1887.

Compared with eastern colleges, more of the early California colleges admitted women. Even so, as was the case in the East, separate women’s colleges began to appear, notably Mills College, chartered in 1885 as a private, nondenominational women’s college.

Denominational colleges were older than the nation itself. Public universities—nondenominational, tax-supported—appeared in a few places after the American Revolution, but most public universities were created only after 1862, when Congress approved the Morrill Act, giving land to states for use in funding a university. The University of California derived from both traditions. The College of California, founded in 1853 as a private academy, drew upon the traditions of Harvard and Yale. In 1867, the trustees donated their institution to the state. The legislature added to that gift the state’s land grant under the Morrill Act and created the University of California. In 1873, the university acquired a medical college in San Francisco. As was occurring elsewhere, the university moved away from its original classical curriculum and created majors, including engineering, agriculture, and commerce. The university also increased its emphasis on research and service to the state.

The need for better-trained teachers led the legislature to create statefunded, two-year schools called “normal schools.” These institutions bore little resemblance to the colleges of the day. Instead of the classical curriculum or the new system of majors, they concentrated on training teachers for grades one through eight. By 1900, state normal schools operated at Chico, Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, San José, and Santa Barbara.

Leland and Jane Stanford spent years planning a university to memorialize their son. They envisioned Stanford University as a nondenominational, “practical” university whose graduates would be both broadly educated and prepared for a profession. Women were admitted on a basis of equality with men. The first president, David Starr Jordan, sought to mold a modern university, stressing research as well as teaching, providing graduate as well as undergraduate instruction, and permitting students to choose a major.

Throughout the nation at the time, public schooling usually ended after the eighth grade. This sufficed for those who worked in agriculture or industry but not for college admission. Those who attended college often prepared at private academies. During the Gilded Age, urban school districts began to create high schools. High schools prepared students for college, and by 1900 some high schools also offered vocational courses such as bookkeeping or woodworking. By 1900, 32 percent of California men and 39 percent of California women of high school age were in school.

Changing Gender Roles

Increasing participation by women in education was just one indication of the changes in women’s status. Another highly visible change was an increase in women throughout the work force—as wage earners, professionals, and self-employed entrepreneurs. These patterns were most pronounced in urban areas.

Many California women worked outside the home, including in 1880 onequarter of San Francisco’s females over the age of 10. African American women and daughters of immigrants were most likely to work for wages. The largest number who worked outside their own homes were servants and waitresses; the next largest number worked in clothing making, either as factory workers or self-employed dressmakers or milliners. By 1900, women outnumbered men by four to one among stenographers and typists and by three to one among teachers. California women were also working in printing (one in eight were women), medicine (also one in eight), and business (one in four among bookkeepers and accountants). By the late 19th century, changes in retailing— especially the appearance of department stores—also brought new employment opportunities for women. In 1874, Kate Kennedy, a San Francisco school principal and political activist, persuaded the legislature to require that women teachers be paid the same as male teachers for the same work, but the large majority of women still earned less than their male counterparts.

Still, the majority of California women did not work outside the home, and the social values of domesticity and separate spheres prevailed in most places, especially among the urban, white middle class. Women continued to be active in church organizations and benevolent societies. By 1894, the 204 charitable organizations in San Francisco dispensed more than $1.3 million, nearly all from private sources. Middle- and upper-class women ran most of those charities. They also organized women’s clubs devoted to self-education, socializing, and often charitable or reform activities. Throughout the nation, and in much of California, the largest women’s organization of the Gilded Age was the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). Founded in 1874, the WCTU advocated the prohibition of alcoholic beverages and condemned the abuse of wives and children by drunken husbands.

Phoebe Apperson Hearst stands out among the California women involved in philanthropy. Born into modest circumstances, her life changed dramatically when she married George Hearst in 1862. Like other wealthy women, she participated in a wide range of civic and philanthropic activities, especially those that focused on women and children. She helped to support an orphanage, a school for female physicians, the first kindergartens in San Francisco (which provided child care for working-class mothers), and a settlement house (which provided social services for the poor). When George died in 1891, Phoebe inherited everything, allowing her to increase her philanthropic endeavors. She helped organize the Parent Teacher Association and gave generously to the Young Women’s Christian Association. Her desire to help young women get an education led her to contribute generously to the University of California, funding buildings, archeological expeditions, an anthropological museum (named in her honor in 1991), and other programs. In 1897, Governor James Budd appointed her to the university Board of Regents, and she was reappointed until her death in 1919. Thus, Hearst reflected many of the expectations of her day about women’s social roles even as she challenged many constraints on women’s involvement in the wider sphere of life, beyond the home and the family.

Other California women also challenged restrictions on women. Two pioneer female lawyers, Clara Shortridge Foltz of San José and Laura de Force Gordon from San Francisco, promoted an array of women’s issues, from admission to law school to changes in laws governing property ownership. (See p. 191 for their accomplishments during the state’s second constitutional convention.) Both, at different times, led the California State Woman Suffrage Association. In 1878, California Senator Aaron A. Sargent introduced in the U.S. Congress, for the first time, a proposed constitutional amendment for woman suffrage. A group of California women steadily promoted the cause of woman suffrage, but they could not persuade the state legislature to put the question before the voters until 1896. Susan B. Anthony and other national suffrage leaders then hurried to California to organize the most thorough campaign up to that time. Ellen Clark Sargent, widow of the senator who first introduced the suffrage amendment, led the effort. The cause won support from Jane Lathrop Stanford, the first time that suffrage secured public support from a woman of such high status. Liquor industry leaders became alarmed that a suffrage victory might lead to a WCTU victory, and they mounted a strong anti-suffrage campaign. Outside San Francisco and Alameda County (Oakland) the suffrage amendment won a small majority, but large majorities against it in those two counties defeated it.

Urban areas also became the sites for a new type of challenge to accepted gender roles. A few men and somewhat more women changed their dress and behavior, passing for a member of the other sex either briefly or permanently. Lillie Hitchcock Coit was a wealthy San Franciscan who occasionally wore men’s clothing to attend saloons or nightspots that barred women. Elvira Mugarrieta claimed that she wore men’s clothing so she could “travel freely, feel protected and find work,” and spent much of her life passing as a man, serving as a lieutenant in the Spanish-American War and a male nurse during the San Francisco earthquake.

Though some people passed for the other gender, homosexual behavior was illegal everywhere. Same-sex relationships that involved genital contact violated state laws and social expectations. In the late 19th century, however, burgeoning cities provided anonymity for gays and lesbians, who gravitated toward cities and developed distinctive subcultures. By the 1890s, reports of regular meeting places for homosexuals—particular clubs, restaurants, steam baths, parks, and streets—came from most large American cities, including San Francisco.

California Indians

The legal situation of California Indians continued to evolve in unusual ways. Throughout the West during the 1870s and 1880s, federal policy and the army combined to locate Indian people on reservations. Efforts to move the native peoples of California onto reservations in California had been short-circuited before the Civil War (see p. 138), though a few small reservations were established and Indian peoples from several tribes were relocated to them. Most remained outside those reservations, however, living in small villages, called rancherías, and working for wages on nearby farms and ranches. Some rancherías existed because local landowners needed the labor of their residents. Sometimes Indian people pooled their resources and bought small plots of land for their rancherías. For most California Indians not living on reservations, however, their legal status remained ambiguous.

The last armed conflict between the U.S. Army and Indian peoples within California was the so-called Modoc War of 1872–1873. The Modocs had traditionally lived in northern California along the Lost River. In 1864, they were assigned to a reservation in southern Oregon with the Klamath people, traditional adversaries of the Modocs. A group of Modocs led by Kientpoos (also spelled Keintpoos or Kintpuash)—often called Captain Jack—returned to the Lost River region and asked for a reservation there. Sporadic negotiations produced no agreement. U.S. troops arrived in 1872 and ordered the Modocs to return to Oregon. Shooting broke out when one Modoc refused to surrender his gun, and the Modocs fled. Several Modocs then killed 17 white settlers. Ordered to negotiate rather than attack, General Edward Canby opened discussions. Among the Modocs, one faction persuaded the rest that they could improve their bargaining position if they could demonstrate their power by killing the negotiators.

Rumors were rampant about the planned killings. The negotiators knew of the danger but came to the meeting place unarmed on April 11, 1873. Two, including Canby, were killed and another seriously injured. (Canby was the highest-ranking army officer ever killed by Indians.) The Modocs fled into what is now the Lava Beds National Monument. The army ordered the new commander to capture the Modocs. Though they first eluded the troops, eventually all were captured. Those who had murdered the peace negotiators were tried and found guilty. Four were hanged, and two sentenced to prison. Meanwhile, Oregon settlers killed several Modocs. Arguing that white settlers were likely to kill the others if they returned to Oregon, federal authorities sent them to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) and permitted them to return to Oregon only 30 years later.

Changing Patterns of Ethnicity

For the United States, the years between the Civil War and World War I (1865–1917) were a time of large-scale immigration, mostly from Europe. California received large numbers of European immigrants, but also had its own unique immigration patterns. Streams of immigrants from Europe and Asia significantly affected Californians’ understanding of ethnicity.

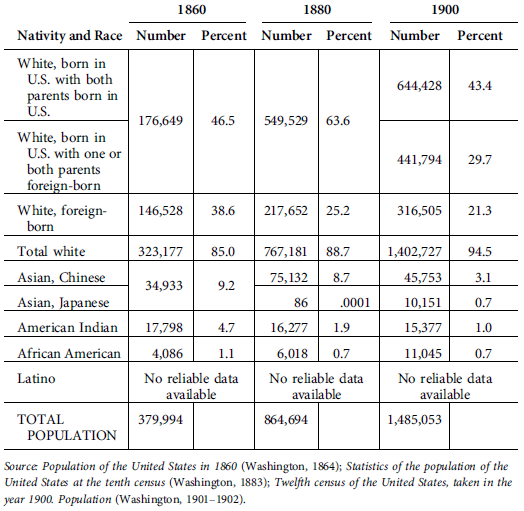

Table \(6.1\) summarizes data on immigration, nativity, and race from the U.S. censuses of 1860, 1880, and 1900. The data for 1860 show the influence of the Gold Rush, when people from around the world descended on California to strike it rich. Immigration continued afterward, but there also developed a large population born in the United States and, especially, in California.

Table \(6.1\) shows that half the population of California, as of 1900, consisted of first- or second-generation white immigrants, the vast majority from Europe. As of 1900, the largest numbers of California’s immigrants were from Germany and Ireland, each with 19 percent of white immigrants, followed by Britain and English-speaking Canada, with 15 percent. Italy and Scandinavia (Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Iceland) each provided 6 percent.

In California, some European ethnic groups showed patterns of settlement and occupation significantly different from those groups elsewhere in the country. In the Midwest, Scandinavians were among those most likely to be farmers. While some Scandinavians farmed in California, many Scandinavians worked as merchant seamen. A survey by the Sailors Union of the Pacific (SUP) found that 40 percent of its members were born in Scandinavia. Andrew Furuseth, a Norwegian-born seaman, helped to create the SUP and led it for more than 40 years. In the northeastern United States, Italians tended to be urban and

Table \(6.1\) Nativity and Race, 1860, 1880, and 1900

to work in manufacturing. There were Italians in California who did the same, but there were also many who lived in agricultural areas, especially around San Francisco Bay. Italian farmers around the bay and in the Santa Clara and Sacramento Valleys sent much of their produce to San Francisco, and Italian produce merchants in San Francisco developed long-term relations with Italian farmers. Such contacts helped Amadeo P. Giannini when he made the transition from produce merchant to banker and created the Bank of Italy in 1904. Other Italians moved from selling produce to processing it, including winemaking, pasta making, and the canning of fruits and vegetables.

In many places in California, European immigrants settled into communities defined by language and religion. Most Italians and most Irish were Catholic, so, for both groups, language, religion, and national origin coincided to help create ethnically self-conscious communities. Germans, however, often formed separate ethnic communities by religion—Catholic, Lutheran, Calvinist, and Jewish—although some German ethnic organizations and newspapers crossed religious dividing lines. Though most Scandinavians were Lutheran, their churches in America often differed significantly from those by German Lutherans. Many Norwegian Lutherans, for example, opposed the consumption of alcohol but few Germans saw any sin attached to a glass of beer.

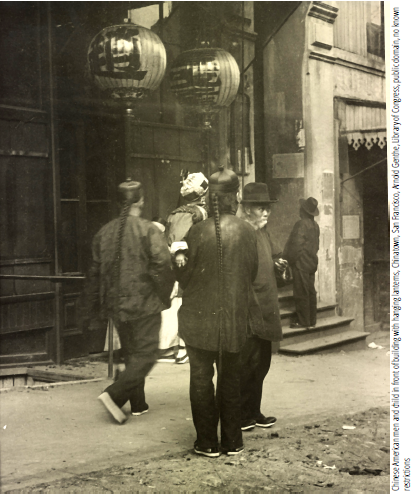

In San Francisco and throughout the West, Chinese immigrants established Chinatowns—relatively autonomous and largely self-contained Chinese communities. Chinese Californians formed kinship organizations and district associations, whose members came from the same part of China, in order to assist and protect each other. A confederation of such associations with headquarters in San Francisco, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association— the “Six Companies”—eventually exercised great power over the social and economic life of Chinese communities throughout the West. Chinese communities were largely male, partly because of a federal law, the Page Act of 1875,

Taken in the late 1890s, this photograph depicts San Francisco's Chinatown before it became a tourist destination. Note the hanging lanterns, traditional clothing of the men and child, and how carefully the man is holding the child.

which prohibited “the importation into the United States of women for the purposes of prostitution.” This law was often used by immigration officials to exclude Chinese women, thus limiting the possibilities for the creation of families. As in other largely male communities, gambling and prostitution flourished, giving Chinatowns a reputation as vice districts.

Many Chinese immigrants initially came to California for the Gold Rush and railroad construction. During the 1850s and 1860s, four-fifths of Chinese Californians lived in mining regions, and nearly that large a proportion worked in mining. By 1900, however, nearly half of all Chinese Californians lived in the San Francisco Bay area and another quarter in the Central Valley. By then, about one-fifth of Chinese Californians worked in agriculture or fishing, another one-fifth as barbers, cooks, household servants, and the like, and another fifth as laborers. By 1900, the total number of Chinese Californians had declined significantly, from a high point of some 136,000 in 1883 to fewer than 46,000 by 1900.

These changes in the number and in the regional and occupational distribution of Chinese Californians reflect, in part, general economic changes. As mining declined, agriculture rose. But those changes also reflect the response by Chinese Californians to white mobs who tried to drive the Chinese out of particular occupations and particular communities. A wave of riots took place in the 1870s, accompanying the economic downturn of those years. Some white workers blamed the Chinese for driving down wages and causing unemployment. In 1871, an anti-Chinese riot in Los Angeles erupted when city police, breaking up a fight in the city’s Chinatown, were fired upon, wounding two policemen and killing a civilian. A white mob surged into Chinatown, burned buildings, looted stores, and attacked Chinese, killing 18. San Francisco experienced anti-Chinese rioting in 1877. A second wave of anti-Chinese riots sweptcommunities in the West in 1885. Anti-Chinese violence led many Chinese to retreat to the agricultural areas of central California and to the larger Chinatowns, especially San Francisco. Declining numbers of Chinese Californians also reflect a return to China by some, the exclusion of new immigrants after 1882, and the limited prospects for forming families.

In parts of California, the Chinese encountered segregation similar to that imposed on blacks in the South, including residential and occupational segregation resulting from local custom rather than law. In 1871, the San Francisco school board barred Chinese students from the public schools, and the ban lasted until 1885, when, in response to the lawsuit brought by the parents of Mamie Tape, the city opened a segregated Chinese school. Segregated schools for Chinese American children were also established in Sacramento and a few other places.

In places with many Chinese immigrants, merchants often took the lead in establishing a strong economic base. Chinese organizations sometimes succeeded in fighting anti-Chinese legislation. For example, when the San Francisco Board of Supervisors restricted Chinese laundry owners, they went to court. In the case of Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886), the U.S. Supreme Court for the first time declared a licensing law unconstitutional because local authorities used it to discriminate on the basis of race.

There was relatively little immigration from Latin America to California between the Gold Rush and about 1900. Many immigrants who came from Latin America to California during the Gold Rush assimilated into Mexican communities that predated the Gold Rush. By 1900, people born in Mexico made up only three percent of foreign-born Californians. Most California Latinos, by 1900, had been born in California, and often their parents had been as well. In Los Angeles, only 11 percent of the Latino population had been born in Mexico as of 1880. Research on several southern California communities indicates very little change between 1860 and 1880 in the number of Latinos.

Historians have described a process that Albert Camarillo calls “barrioization”—the creation of barrios, separate Spanish-speaking neighborhoods within the cities, often near an old mission church. Such barrios, like neighborhoods of European immigrants, provided their residents with opportunities and institutions to preserve their own cultural heritages even as they adapted to the expectations and opportunities in the larger community. Large barrios often had a newspaper, stores run by members of the group where one might buy culturally familiar products, and voluntary organizations including church-related groups, beneficial societies, and political clubs. There was, of course, one glaring difference between immigrant neighborhoods and barrios—European immigrants chose to migrate, seeking improved opportunities and a better life, but Mexican Californians went from being the dominant group to a disadvantaged and largely landless minority, with well over half of the males employed as unskilled laborers.

In the late 19th century, ethnicity played a prominent role in the way many Californians identified themselves. Foreign immigrants to California began to think of themselves as having much in common with others who spoke their language, worshiped as they did, and shared many of their values and expectations, whether or not they came from the same village. They thought of themselves as members of an ethnic group, different from the groups around them. Not surprisingly, for many Californians of the late 19th century, ethnic identities proved to be an important part of their self-identity and affected the way that they related to others.