6.1: The Economic Transformation of California and the West

- Page ID

- 126969

Railroad construction was important to economic development throughout the United States after the Civil War. In California and the West, railroads were even more crucial because of the great distances and the dearth of navigable waterways. Mining continued to be a major element in the western economy. At the same time, agriculture emerged as California’s leading industry. And, increasingly, water stood out as indispensable for mining, agriculture, and urban growth.

Railroad Expansion

For a quarter of a century after Leland Stanford placed the golden spike, the Central Pacific Railroad and its successor corporation, the Southern Pacific, dominated rail transportation in California and other parts of the West. Even before 1869, the railroad’s “Big Four”—Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker—had begun to buy out potential rivals and block possible competitors.

San Francisco entrepreneurs organized the Southern Pacific Railroad to build a line from San Francisco to San Diego, and in 1866 Congress gave the Southern Pacific a generous land grant. The Big Four gained control of the Southern Pacific (SP) and plotted a route through the Santa Clara and San Joaquin Valleys—giving them not only a transportation monopoly there

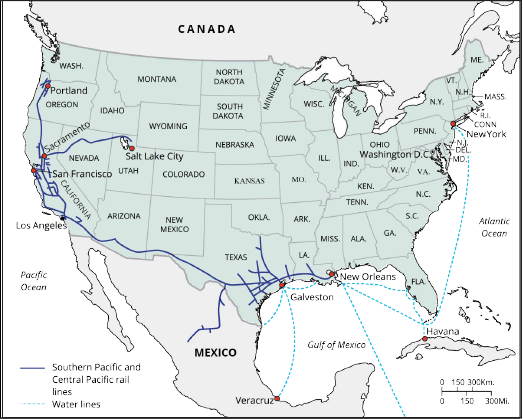

Map \(6.1\) This map shows the extent of the Southern Pacific's transportation system as of 1894. The Southern Pacific dominated railroad service in California and nearby areas and connected California to New Orleans, the Pacific Northwest, and the Midwest (via the connection in Utah with the Union Pacific). Southern Pacific water routes connected New York and other major eastern cities to New Orleans, making it possible to travel cross-country entirely on Southern Pacific facilities. Does this map help you to understand why the Southern Pacific was sometimes called "the octopus"?

but also a great deal of potentially valuable agricultural land as part of their land grant. In 1870, the SP reached Los Angeles, then a country town with fewer than 6000 people.

By the mid-1870s, the Big Four controlled 85 percent of all railroad mileage in California and had ambitious plans for expansion. Eventually, they operated a line across Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas to New Orleans. Another line ran north, through the Sacramento Valley, then to Portland, Oregon (See Map \(6.1\)). They acquired fleets of ships that carried passengers and freight along the Pacific coast, between California and Japan, and between New Orleans and New York. In 1884, they merged all these operations into the Southern Pacific Company, a holding company for which Huntington secured a corporate charter in Kentucky after the California legislature balked at approving such a powerful corporation. By 1884, the Big Four claimed that the SP was the largest transportation system in the nation, with more than 9000 miles of rails, 16,000 miles of water lines, and a virtual monopoly within California and other parts of the West.

The SP was also the largest landowner in California. While other landgrant railroads sold much of their lands, the SP held most of its land, arousing opposition from would-be farmers. On occasion, conflict over land erupted into violence. The most famous conflict was the “battle of Mussel Slough,” a struggle between the SP and farmers near Hanford, in what is now Kings County. Residents of the area had filed lawsuits over the SP’s land grant, and many farmers hoped to purchase land from the federal government for $2.50 per acre, rather than from the SP. The SP prevailed in court, however, and enforced prices of $10 to $25 per acre. In 1880, a federal marshal set out to evict a farm family, but a group of armed farmers blocked his way. Seven men died in the shootout that followed.

Leland Stanford served as president of the Central Pacific and then the SP. A founder of the Republican Party in California and the state’s first Republican governor (1863–1865), Stanford won election to the United States Senate in 1885. He and his wife, Jane Lathrop Stanford, had one child, Leland Jr., who died of typhoid at the age of 16. They created a magnificent memorial to their son: Stanford University.

Collis P. Huntington was the shrewdest, coldest, and perhaps most ambitious of the Big Four. He represented them in the East and soon considered New York City his home. Huntington invested in other railroads, and by 1884 he could ride in his personal rail car over his own companies’ tracks from the Atlantic to the Pacific! He also invested in railroads in Latin America and Africa, urban transit in Brooklyn, land in southern California, shipbuilding in Virginia, and a host of other companies. True to his opposition to slavery in the 1850s, he insisted that his companies pay African Americans the same as white workers and that African Americans be hired on an equal basis with whites. His few charitable contributions included funds for schools for African Americans.

No other railroad challenged the SP’s dominance until the 1890s, and the company acquired a reputation for charging “all the traffic will bear,” that is, charging for freight and passengers at the very highest possible rate. Such behavior was typical of most railroad companies at the time. More than one entrepreneur reported that, upon his complaining about high freight rates, SP officials asked him to produce his account ledgers so that they could determine the highest level of freight rates he could pay without going bankrupt.

Most Californians understood the SP to be the most powerful force in state and local politics. All of the Big Four had taken part in Republican politics in the 1850s, before their investment in the railroad. Stanford served as governor and U.S. senator. Huntington was the SP’s lobbyist in Washington, dedicated to preventing political restrictions on the SP and to gaining whatever advantages could be realized through the political process. In the early 1880s, the widow of David Colton, a high-ranking official of the SP, released letters that Huntington had written to her husband in the 1870s. In one of the most notorious, Huntington wrote about one California congressman: “He is a wild hog; don’t let him come back to Washington.” Another letter dealt with the U.S. Congress: “It costs money to fix things . . . with $200,000 I can pass our bill.”

Competition for the SP arrived in 1885 in the form of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad, known as the Santa Fe, which completed its line into Los Angeles in 1885. By 1888, passengers could take the Santa Fe from Chicago to San Diego, and a fare war broke out between the Santa Fe and the SP as each tried to undercut the other’s fares. In the meantime, several San Francisco merchants formed the Traffic Association to consider alternatives to the SP and to encourage the legislature to regulate freight rates. Eventually, these efforts produced a new railroad company to build a line through the San Joaquin Valley to compete with the SP. Construction began in 1895, and by 1898 a line ran between Stockton and Bakersfield. The Santa Fe then bought the new line, linked it to the Santa Fe in southern California, and, in 1900, completed an extension to San Francisco Bay. The SP’s monopoly had finally been broken.

Despite complaints about railroad rates and political influence, rail lines were enormously important to the economic development of the West. Without the railroad, most goods moved by water—up and down the coast and along the few navigable rivers of central California. The railroad permitted mining in remote regions and the shipping of heavy, technologically advanced mining equipment. Additionally, the railroad encouraged the development of specialized agriculture, especially fruit growing, that required fast trains and refrigeration equipment to carry produce from California to markets on the other side of the nation. By making travel from the eastern United States to California both easy and cheap, railroads also contributed significantly to the growth of the tourist industry and the state’s population boom.

Mining and Finance

Mining continued to be centrally important to the state’s economy, not only within California, but also for the activities of California companies in developing mines throughout the West. Many aspects of mining required a high degree of expertise, technologically advanced equipment, and large amounts of capital. By the 1870s, California, and San Francisco in particular, were providing all three of these elements for mining throughout the West. In the process, the initiative in mining shifted from prospectors and mining engineers toward well-capitalized mining companies and investment bankers.

Nevada’s Comstock Lode (see p. 149) made some Californians wealthy. Between 1859 and 1880, a third of a billion dollars in silver (equivalent to about 6 billion dollars in 2010) was taken out of the Comstock Lode. Comstock mining required digging deep shafts and installing complex machinery to move men and equipment thousands of feet into the earth and to keep the tunnels cool and dry. By the mid-1870s, the Comstock mines used some of the most advanced mining equipment in the world.

The career of George Hearst illustrates the role of Californians in western mining. Born in Missouri in 1820, Hearst came overland to California in 1850 and acquired extensive mining experience. In 1859, he bought a one-sixth interest in the Ophir mine in the Comstock. The Ophir proved extraordinarily profitable. Hearst invested his profits in mining and in agricultural and timber lands throughout the West and Mexico. A Democrat, he served in the United States Senate from 1886 until his death in 1891. Though Hearst became wealthy from his mining investments, his fortune did not place him in the top ranks of San Francisco’s financial elite. Those positions were held securely by the Big Four and others who were even more successful than Hearst in coaxing profits from the Comstock.

The first Californians to rake in extraordinary profits from the Comstock were William Ralston and William Sharon. Ralston had organized the Bank of California in 1864 and soon set up agencies in the Comstock region. Sharon, Ralston’s representative there, established control over many mines in the region, and he also centralized decision making, financed deeper operations, and discovered new ore bodies. He vertically integrated the industry, combining ownership of mines with ownership of a crushing mill, a timber company for shoring up the deep tunnels, water for the mills and for cooling the mines, fuel, and, after 1872, a railroad connection between the Comstock and the Central Pacific. In 1873, he was elected to the United States Senate from Nevada.

Nevada silver earned large profits for Ralston’s Bank of California. He invested some of this capital in manufacturing, mostly in San Francisco, including foundries and iron works, a refinery for Hawaiian sugar, and woolen mills to make cloth from the wool of California sheep. Other investments included shipping, hydraulic gold mining, insurance, irrigation canals, and the Palace Hotel, modeled on the great luxury hotels of Europe. He also loaned funds to the Central Pacific. In 1875, however, Ralston faced a financial crisis. Some investments had been hit hard by the nationwide economic depression that began in 1873, and some factories were suffering from competition with the products of eastern factories, now shipped to California over the railroad that Ralston had helped to finance. His back to the wall, Ralston sold his half of the Palace Hotel to Sharon, disposed of other stock as best he could, and resigned from the bank. He died the same day. Sharon took his place as head of a reorganized Bank of California.

By the time Sharon took over the Bank of California, he and the bank had already been displaced as the dominant factors in Nevada silver mining. They lost out to four partners, James G. Fair and John W. Mackay, both experienced mine operators, and James C. Flood and William F. O’Brien, San Francisco saloon keepers turned stockbrokers. These four—all Irish—wrested control of one large mine from Sharon in 1868, and the mine almost immediately began to produce large profits. They soon struck the richest vein of silver ore in American history. Like Sharon before them, they vertically organized operations, investing in a reducing mill and in timber and water companies, all of which profited so long as the mines remained productive. Like others of the era, they invested their profits widely. Flood took the lead in creating the Nevada Bank of San Francisco in 1875 and served as its president. For a brief time, the Nevada Bank claimed the largest capitalization of any bank in the world.

San Francisco was the financial center of the Nevada silver boom and of mining throughout the West. The city’s merchants sold supplies to the miners, and most stocks in mining companies were bought and sold at San Francisco’s Mining Exchange, scene of quick profits and devastating losses. Initially, some San Francisco bankers, like Ralston, relied for capital on California merchants who had prospered during the Gold Rush. San Francisco bankers used their access to capital not just to invest in the Comstock but to centralize economic decision making there and to introduce more productive technologies. San Francisco bankers financed much of the West’s mining operations, and the profits helped to develop California industries, as well as to build lavish mansions for the fortunate few. The process not only confirmed San Francisco as the financial capital of a self-financing frontier, but also reinforced the speculative mentality of the Gold Rush.

Agriculture

The 1870 census recorded that wheat had surpassed gold as California’s most valuable product. Wheat remained one of California’s most valuable products for the next 30 years, a period historians call the Bonanza Wheat Era. This massive increase in production occurred largely because of the expanding industrial work force of Britain, which required the importation of food. California’s weather in the central valleys was conducive to the production of hard, dry wheat suitable for the long sea voyage and highly prized by British and Irish milling companies.

The high demand for California wheat and the relatively flat and dry California terrain led to mass production. Agricultural entrepreneurs carved out huge wheat farms—the largest extending over 103 square miles—and came to rely on machines to a greater extent than wheat farmers anywhere else, particularly on larger and more complex machines. Relatively flat terrain and large fields encouraged California wheat growers to use huge steampowered tractors and steam-powered combines, which cut the standing wheat and separated the grain from the stalk in one operation. Not for another 20 years or so was such equipment widely used elsewhere.

Other agricultural entrepreneurs also operated on a large scale. Henry Miller and Charles Lux were German immigrants, both butchers. They formed a partnership and quickly moved to meatpacking (selling meat wholesale) and to cattle raising. Their company became the largest meat-packing firm in the West and the largest landowner in the San Joaquin Valley, where the company undertook massive drainage and irrigation projects to transform the landscape into fields and pastures. Eventually, Miller and Lux owned or leased thousands of square miles of land in three states. By 1900, the firm was the nation’s largest vertically integrated cattle-raising and meat-packing company, and the only agricultural corporation ranked among the 200 largest industrial corporations nationwide.

The bonanza wheat farms required a large force of laborers, especially at planting and harvesting times, as did the mammoth cattle ranches of Miller and Lux. Such operations gave a unique character to California agriculture— the farms and ranches were on a scale virtually unknown elsewhere in the country, and they relied on both technologically up-to-date equipment and an army of wage laborers, many of whom could only count on seasonal employment. By 1900 or so, the Bonanza Wheat Era had passed, partly because expansion of wheat growing elsewhere in the world drove down prices, and the Miller and Lux empire also dissolved after Miller’s death in 1916.

Viticulture—the growing of grapes—had been well established in southern California by the Spanish missions. In the 1860s and after, grape growing for wine shifted northward, and the valleys around San Francisco Bay—Sonoma, Napa, Livermore, and Santa Clara—became the center of the California wine industry. There the climate, terrain, and soil produced grapes that could be made into high-quality wines. By 1900, California was making more than 80 percent of the nation’s wine. Grape growers, especially in the San Joaquin Valley, discovered another market for their products in the form of raisins, and by 1900 almost half of the California grape harvest was used for raisins.

During the 1880s and 1890s, fruit growers began to expand and diversify, especially around San Francisco Bay and in parts of the San Joaquin Valley. Climate and soil conditions gave California fruit growers a great advantage over other parts of the country, and new techniques in preserving fruit meant that dried and canned fruit from California could easily be shipped to the eastern states and elsewhere in the world. The development of refrigerated railroad cars greatly increased the ability of California growers to sell fresh fruit. The first refrigerated shipment of California fruit arrived in New York in 1888, leading to a major increase in demand. Refrigeration technology was soon applied to ships, and by 1892 fresh fruit from California was available in Great Britain. By 1900, Santa Clara County led the state in fruit production by a wide margin, followed by Fresno, Sonoma, and Solano Counties. In the 1870s, the U.S. Department of Agriculture introduced California growers to a navel orange from Brazil that was superior to previous varieties. Orange growing expanded rapidly in southern California once refrigerated railroad cars opened markets in the eastern states. In the 1880s and 1890s, California also became an important producer of vegetables and nuts.

The transition to fruit, nut, and vegetable crops brought important changes in many other aspects of California agriculture. The enormous wheat ranches and the vast cattle ranches yielded to smaller farms that relied more on human labor than on machinery. Raisin, peach, plum, and pear growers averaged between 10 and 75 acres per farm, as opposed to the thousands of acres that had composed some wheat or cattle ranches. In many cases, a single family ran these small operations, although harvesting usually required additional labor.

The agricultural work force in central California in the 1880s and 1890s was ethnically diverse, including immigrants from Europe and whites whose families had been in the United States for generations. Cattle raising often employed Latinos, including both descendants of Californios and more recent immigrants from Mexico. Chinese farm workers contributed to the development of specialty crop agriculture out of proportion to their numbers. By the 1890s, there were also increasing numbers of agricultural workers from Japan and India.

Water

Water was key for the success of fruit, nut, and vegetable growing. Miners had developed elaborate water systems almost immediately and continued to require large amounts. Burgeoning urban areas required more and more water. Demands for water came up against legal systems that had been devised for different conditions. As a result, conflict over water often led to protracted legal battles and produced, in the end, new legal definitions of water rights and one of the first court orders protecting the environment.

Hydraulic mining had been used since the early 1850s (see p. 116). By 1880, some hydraulic mining operations operated around the clock, lit by giant electrical floodlights and drawing water from large reservoirs constructed by damming rivers. Unfortunately, hydraulic mining was highly destructive not only to the terrain where the water cannons were directed, but also to the environment downstream. The water from the blasting drained into rivers, carrying with it debris that killed fish and made the water unsuitable for drinking. Mining debris filled river channels and created serious flooding. Those floods scattered mining debris over a wide area and damaged agricultural land. Urban residents far downstream from hydraulic mining had to build elaborate dikes to keep rivers from flooding their cities. The mining debris in the river channels also threatened the use of rivers for shipping.

Finally, in 1884, Federal Circuit Judge Lorenzo Sawyer issued an order in the case of Woodruff v. North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company prohibiting the dumping of debris in the rivers on the grounds that it was “a public and private nuisance,” and inevitably damaged the property and livelihood of farmers. It was, perhaps, the first federal court order restricting a business in order to protect the environment. The SP backed those challenging hydraulic mining because debris caused problems for the railroad too, by fouling its tracks and damaging its land. The Sawyer decision, which ended nearly all hydraulic mining, symbolized the transition from mineral extraction to crop production.

The legal system that Californians adapted from the eastern states was ill suited to the West. Eastern water law emphasized riparian rights, that is, the right of all those whose land bordered a stream to have access to the full flow of water from the stream, less small amounts for drinking. Irrigation removed water from the stream permanently, violating the riparian rights of those downstream from the irrigator. A different practice had emerged in the gold country, where the principle of appropriation was used to argue that the first person to take water from a stream gained the rights to that water. Both systems received some legal sanction by the California legislature.

This confusing state of affairs came under increasing challenge as more and more farmers began to use streams for irrigation. Eventually, in 1887, the legislature approved a law that permitted residents in a particular area to form an irrigation district with legal authority to take water for irrigation regardless of downstream claims. By then, California led the nation in the amount of irrigated farmland. By 1889, 14,000 California farmers (a quarter of the total), most of them in the San Joaquin Valley, practiced irrigation on more than a million acres, about eight percent of all improved farmland in the state.

As irrigation was transforming parts of the Central Valley previously too dry for many crops, wetlands were being drained to make them, too, available for farming. In the middle of the 19th century, the southern end of the San Joaquin Valley held the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River. Tulare Lake was broad—covering as much as 790 square miles—but shallow, and ringed by wetlands thick with tules and a wide diversity of wildlife. But as irrigators began to divert the rivers that fed Tulare Lake, the lake dried up. By 1900, the lake bed was being used for agriculture. Throughout the Central Valley, other wetlands were also drained for use as farmland. Draining wetlands together with massive irrigation projects produced unprecedented alterations in the landscape, to the point that the Central Valley now has deservedly been called “one of the most transformed landscapes in the world.”

In the 1870s, some companies that had initially been formed to supply water for gold mining began to sell water to cities and for irrigation. To meet the demand for electricity in the late 1880s and after, entrepreneurs in most California cities were building generating plants that burned coal. Some, however, began to adapt the miners’ waterways and high-pressure technologies to generate electricity more cheaply and with less pollution. By the early 1890s, there were several hydroelectric generating plants operating in the gold country. Mining towns like Grass Valley were among the first to have lights from hydroelectric power. By 1900, there were 25 hydroelectric generating plants in California, most in northern California, and that area was well on its way to becoming the region of the nation with the most intense use of water power to generate electricity.

Rise of Organized Labor

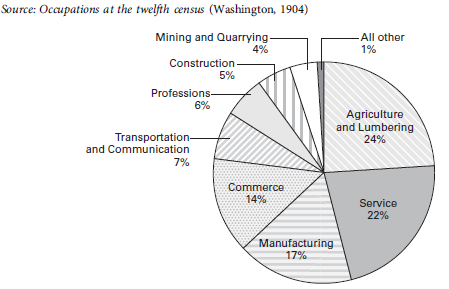

During the Gilded Age, changes in the state’s economy resulted in a more complex work force. Figure \(6.1\) indicates components of the work force, based on the 1900 census. The census data understate the number of women who worked in agriculture, so that proportion could be as high as a third. Also, women who ran boarding houses and prostitutes were often undercounted, which would increase the service sector somewhat. Increasing the agriculture and service sectors would, of course, proportionately decrease the others. Otherwise, Figure 6.1 provides a reasonable approximation of the California work force.

As the scale of operations grew in mining, transportation, and some parts of agriculture and manufacturing, and as reliance on technologically

Figure \(6.1\) Major Components of the Wage-Earning Work Force, 1900

This graph suggests how complex the California economy had become by 1900. It also points to the continuing importance of agriculture and lumbering, as well as to the major role of manufacturing

sophisticated machinery increased in those areas, fewer people had the necessary capital to enter such fields. Instead, those who worked in these fields were increasingly likely to be wage-earning employees. Some of them helped to organize unions. In 1910, Lucile Eaves published one of the first scholarly histories of California labor. In it, she wrote that trade union activity appeared so early “that one is tempted to believe that the craftsmen met each other on the way to California and agreed to unite.” And, indeed, many immigrants to California brought a concept of trade unionism in their mental baggage.

The first recorded union activity in California came in San Francisco in 1849, when carpenters went on strike for higher wages. Local unions were common in San Francisco and other cities from the Gold Rush onward, though most were short-lived until the 1880s. The history of early California unions is much like that of their counterparts to the east—workers with a particular skill formed local unions to seek better wages or working conditions, and those organizations often fell apart if they lost a strike.

As in other parts of the country in the 1880s, many local unions in California affiliated with newly formed national trade union organizations and sometimes with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), organized in 1886. Such trade unions typically limited their membership to skilled workers in one particular field, such as carpentry or printing, and many excluded women and people of color. The 1880s also saw the rapid rise of the Knights of Labor, who admitted both skilled and unskilled workers, including women and African Americans, but the Knights were short-lived. All California unions excluded Chinese workers. In fact, most California unions in the 1880s presented themselves as defending white workers against competition with Chinese workers, arguing that employers

used Chinese workers to drive down wage levels and working conditions. Most historians agree that opposition to Chinese labor gave California unions what historian Alexander Saxton called “the indispensable enemy.” This common “enemy” proved useful in efforts to organize white workers.

Unions also thrived in the prosperous 1880s because many employers found it to their financial advantage to give in to employee demands for better wages, rather than to face a strike. In 1891, employers formed the Board of Manufacturers and Employers of California, centered in San Francisco and devoted to opposing unions. A major depression that began in 1893 caused many unions to collapse when they lost members due to unemployment or were unable to maintain wage levels. Only with the revival of prosperity in the late 1890s did trade unions revive.

San Francisco: Metropolis of the West

The Southern Pacific, Hearst, Sharon, Flood and Fair, cattle barons, lumber companies, and other entrepreneurs located their corporate headquarters in San Francisco, which was, by any criterion of that day, a major city. In 1880, San Francisco’s population reached nearly 300,000, ranking it seventh among the nation’s cities—the only large city west of St. Louis. James Bryce, an English visitor, noted in the 1880s that San Francisco “dwarfs” other western cities and “is a commercial and intellectual centre, and source of influence for the surrounding regions, more powerful over them than is any Eastern city over its neighborhood.”

Beyond being a commercial and literary center, San Francisco had about it an air of excitement. Rudyard Kipling, the British author, visited in 1891 and likened the cable cars to a miracle for their ability to climb and descend hills smoothly. The expanding population alone provided opportunities that couldn’t exist elsewhere. For example, aspiring women artists formed a sketching club to encourage and critique each other’s work, amateur photographers (including Mary Tape) formed the California Camera Club, and German immigrants formed German gymnastics societies and singing groups. Seamen the world over knew of the city’s storied Barbary Coast, reputed to contain every conceivable form of pleasure and vice. San Francisco’s Chinatown was the largest in the United States and already attracted curious tourists—Oscar Wilde, in 1881, thought it was “the most artistic town I have ever come across.”

This photograph of San Francisco, the metropolis of the West, was taken looking southwestward along Market Street. Jack London called the area to the left of Market Street "South of the Slot" (south of the cable-car slot), and described it as home to the city's working class. The area closest to the Ferry Building on both sides of Market Street included many saloons, cheap eating places, and union offices, all catering to the men who worked on the waterfront. Why might newcomers from small towns and rural areas, arriving in San Francisco through the Ferry Building, feel uncomfortable in such surroundings?

San Francisco was the metropolis of the West because of its economic prowess. It was a center for finance and held the headquarters of corporations that dominated much of the Pacific coast and intermountainWest. Its dominance also stemmed from its port: In 1880, 99 percent of all imports to the Pacific coast arrived on its docks, and 83 percent of all Pacific coast exports were loaded there. Western mining, transportation, and agriculture stimulated San Francisco’s manufacturing sector. By 1880, San Francisco’s foundries produced advanced mining equipment, large-scale agricultural implements, locomotives, and ships. San Francisco also became a major center for food processing.

San Francisco’s entrepreneurs extended their reach throughout the West and into the Pacific. Claus Spreckels, an immigrant from Germany, established a sugar refinery in the city in 1863. In the 1870s, he developed a huge sugar plantation on the Hawaiian island of Maui and soon controlled nearly all the Hawaiian sugar crop. By the 1890s, Spreckels was one of the three largest sugar producers in the nation, drawing not only upon Hawai‘i but also on sugar beet fields in several western states. In the late 1890s, Hawaiian-born sugar planters wrested control from Spreckels, then replicated the chain of vertical integration that Spreckels had pioneered, investing in a steamship company to carry raw sugar to the new C&H (California and Hawaiian) refinery they built at Crockett, northeast of San Francisco.

As the population of California’s cities burgeoned, lumberjacks cut the coastal redwoods for use in construction. When timberlands near San Francisco Bay were exhausted, lumbering moved to northern California, Oregon, and Washington. Some lumber companies became vertically integrated, owning lumber mills, schooners that carried rough-cut lumber down the coast, and lumberyards and planing mills in the San Francisco Bay area. Born in Scotland, Robert Dollar grew up in lumber camps and worked his way up to sawmill owner. He purchased a ship in 1895 to carry his lumber to San Francisco and then added more ships. His Dollar Line eventually became a major oceanic shipping company and the predecessor of today’s American President Lines.

Some of California’s Gold Rush fortunes were extended and expanded by a second generation. By 1900, George Hearst’s former newspaper, the San Francisco Examiner, was one of several papers owned by his son, William Randolph Hearst, who created a nationwide publishing empire in the early 20th century. William H. Crocker, son of Charles Crocker of the Big Four, formed Crocker Bank in the 1880s and invested widely throughout the West, including electrical power companies, hydroelectric generating plants, mining, agriculture, shipping, and southern California oil. Claus Spreckels’s son John invested heavily in San Diego in commercial properties, banks, newspapers, and the Hotel del Coronado, the city’s leading tourist attraction. His investments helped San Diego grow to almost 18,000 people by 1900. Henry Huntington—the nephew and heir of Collis Huntington of the SP—created an extensive streetcar system in the Los Angeles basin that both fed upon and contributed to the growth of Los Angeles.