6.3: Politics

- Page ID

- 126971

During the Gilded Age, politics meant political parties. The large majority of Americans expected that only men would be involved, and that men would be steadfastly loyal to their party. Political parties nominated candidates for office at party conventions (at local, state, and national levels), and the conventions were followed by circus-like campaigns. The parties distributed ballots on Election Day—a voter had to get the “ticket” with the candidates of his party in order to vote. In most of the country, ethnicity and loyalty to a party were closely linked. California differed from these national patterns in several ways: some California males seem to have been less strongly committed to their parties, and ethnicity seems less significantly related to party affiliation in California than elsewhere.

Political Discontent in the 1870s

In the 1871 election, the Republicans of Solano County demonstrated the potential for manipulation that was inherent in having political parties print ballots. Normally, parties printed their candidates’ names on a sheet of paper and distributed those “tickets” to voters. If a voter wanted to vote for someone else, he had to scratch out the name printed on the ticket and write in the other name. Some candidates distributed “pasters,” small strips of paper with the candidate’s name on one side and glue on the other, to make “scratching a ticket” easier. Republicans in Solano County devised a ticket only five-eighths of an inch wide and printed in a tiny font, making it impossible to write in a name or use a paster. Its long and narrow shape, with dense, tiny printing all over it, was soon labeled the “tapeworm ticket” and was imitated across the state. In 1874, the legislature required that ballots be “uniform in size, color, weight, texture, and appearance”—one of the earliest efforts by any state to regulate political parties. Another law in 1878 regulated the symbols used by parties to distinguish their tickets.

Newton Booth, who won the 1871 election for governor by running as a critic of the Southern Pacific, took office just as the Granger movement began to affect state politics. The Patrons of Husbandry—called the Grange— promoted educational programs and cooperatives among farmers. In several states, farmers formed independent political parties, known by various names but usually called Granger parties. Several states passed “granger laws,” creating state railway commissions to investigate, and sometimes regulate, railroad charges. In California in 1873, Grangers combined with opponents of the SP to create a new political party, the People’s Independent Party. Governor Booth favored the new party. The People’s Independents won a large bloc of legislative seats in 1873 and elected their candidate to the state supreme court (judges were then elected on party tickets). In 1875, the state legislature was faced with filling both U.S. Senate seats, due to the death of one incumbent and the expiration of the other’s term. People’s Independents combined with Booth’s followers and a few Democrats to elect Booth to one Senate seat and a Democrat to the other. When Booth resigned the governorship, Lieutenant Governor Romualdo Pacheco, scion of a prominent Californio family, became governor for the remainder of Booth’s term. By 1875, the Granger movement had passed its peak, and the People’s Independent Party soon disappeared.

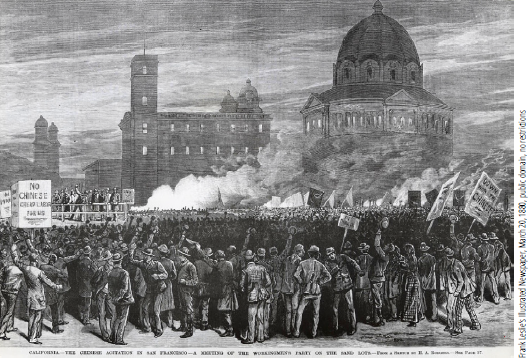

Illustration of a meeting of the San Francisco Workingmen's Party. What does this image suggest about the ability of popular figures like Kearney to deflect white working class grievances onto even more economically marginalized Chinese workers?

Another third party emerged in San Francisco in 1877, during a time of economic depression and high unemployment. In July 1877, a strike by eastern railroad workers, protesting wage cuts, mushroomed into violence in several midwestern and eastern cities. In San Francisco, a meeting to support the railway strikers erupted into a riot aimed at Chinese workers. That fall, Denis Kearney, a drayman whose business had suffered from the depression, attracted a wide following when he condemned the monopoly power of the SP and, at the same time, argued that monopolists were using Chinese workers to drive down wages. He formed the Workingmen’s Party of California (WPC) and gave it the slogan, “The Chinese Must Go.” For a time in the late 1870s, the WPC dominated political life in San Francisco, sweeping elections in 1878 and 1879. WPC candidates also won elections for mayor in Oakland and Sacramento.

Kearney and the WPC were not the first to attack the Chinese. From the start of Chinese immigration to California, some viewed them as a threat. Beginning with Leland Stanford in 1861, most governors bemoaned the presence of Chinese in California. “Anti-coolie” clubs (“coolie” was a derogatory term for a Chinese laborer) in working-class districts of San Francisco attracted many members. Opponents of the Chinese claimed that they drove down white workers’ wages and standard of living. Others portrayed the Chinese as unclean, immoral, clannish, and heathen. State and city laws discriminated against the Chinese from the 1850s onward.

The Second Constitutional Convention, 1878

The WPC’s greatest statewide success came in 1878, in elections for a second constitutional convention. In many places, anxious Republicans and Democrats compromised their differences and put up nonpartisan slates to oppose the WPC. In the end, the convention consisted of 80 nonpartisans, 52 Workingmen (mostly from San Francisco), 10 Republicans, nine Democrats, and one Independent. Of those elected from rural areas, many had been involved with the Granger movement. Together, WPC delegates and Granger delegates comprised a majority.

The convention delegates met in Sacramento in September 1878. The constitution they drafted—much amended—remains the state constitution today. The new constitution set the size of the state senate at 40 and the assembly at 80 (both still in force) and specified that the legislature should meet for 60 days in alternate years (a provision changed in 1966). Statewide officers were to serve four-year terms and be elected in even-numbered years halfway between presidential elections (provisions still in force). The 1849 constitution required publication of all significant public documents in both English and Spanish; the new constitution specified that all public documents be in English. The University of California was given autonomy from legislative or executive oversight (still in force). The WPC and the Grangers combined to create an elected railroad commission (now called the Public Utilities Commission) that was empowered to regulate rates. Water was declared to be under state regulation.

Clara Shortridge Foltz and Laura de Force Gordon (see p. 182) set up a well-organized lobbying operation at the convention. Though unable to get woman suffrage, they secured two important constitutional guarantees: equal access for women to any legitimate occupation and to public higher educational institutions.

The convention teemed with proposals for constitutional restrictions on Chinese and other Asian immigrants. Only one member of the body opposed discriminatory legislation. In the end, the constitution authorized the legislature to provide for removal from the state of “dangerous or detrimental” aliens, prohibited any corporation or governmental body from employing any “Chinese or Mongolian,” directed the legislature to discourage immigration by those not eligible for citizenship (federal law limited naturalization to “white persons” and those of African descent), and specified that white foreigners and foreigners of African descent had the same property rights as native-born citizens.

The new constitution was highly controversial, mostly because of its restrictions on corporations. Californians voted on it in May 1879. Despite strong opposition, it was approved by a healthy margin. The provisions restricting Asians were invalidated by the courts.

Politics in the 1880s

Anti-Chinese agitation soon reached national politics. In 1880, President Rutherford B. Hayes sent a representative to China to negotiate a treaty permitting the United States to “regulate, limit, or suspend” the immigration of Chinese laborers, and the treaty was approved in November. That summer, both Republicans and Democrats promised, in their national platforms, to cut off Chinese immigration.

In 1882, U.S. Senator John Miller, a Republican from California, introduced a bill to exclude Chinese immigration for 20 years and to prohibit Chinese from becoming naturalized citizens. Miller’s bill drew strong support from westerners and from Democrats. It passed both houses of Congress by large margins, prohibiting entry to all Chinese except teachers, students, merchants, tourists, and officials. Most opposition came from northeastern Republicans, especially veterans of the abolition movement. President Chester A. Arthur vetoed Miller’s bill, arguing that it violated the 1880 treaty, that 20 years was too long, and that the bill might “drive [Chinese] trade and commerce into more friendly hands.” In response, Congress cut exclusion to 10 years and stated that the act did not violate the treaty. It now drew even more votes, and Arthur signed the bill into law.

The WPC had risen to prominence on the Chinese issue; however, by 1882, the party had broken into factional disarray and disappeared. State politics in the relatively prosperous 1880s involved Republicans and Democrats, with no significant third parties. The Southern Pacific continued to play a prominent part in state politics—symbolized in 1885 when Leland Stanford was elected to the U.S. Senate amid allegations of vote-buying. In 1886, voters elected a Democrat as governor and a Republican as lieutenant governor, and gave a narrow majority in the legislature to the Democrats. This permitted the Democrats, in 1887, to elect George Hearst to a full term in the U.S. Senate; he had been appointed by the Democratic governor to fill a vacancy the year before.

The 1880s marked the peak of power for Christopher A. Buckley, a blind saloon keeper who, around 1880, emerged as the most powerful Democratic leader in San Francisco. Born in Ireland and raised in New York City, Buckley acquired the reputation of being a “boss,” a party leader whose organization dominated all access to political office by controlling nominating conventions. As “boss,” Buckley used appointive governmental positions to reward his loyal followers. To keep voter support, he kept taxes so low that city government could do little. Buckley apparently extracted a price from many companies that did business with the burgeoning city—when he died, his estate included bonds issued by companies that did business with the city during the 1880s. Buckley also extended his power to state politics, picking the Democrats who won the governorship in 1882 (George Stoneman) and 1886 (Washington Bartlett).

As of 1890, only one candidate for governor of California had ever been elected to a second term, and the governorship and control of the state legislature (and therefore the U.S. senatorships filled by the state legislature) changed parties at almost every election. Throughout the 1870s, third parties—first the People’s Independents and then the WPC—had attracted large numbers of California voters. Yet during much of the Gilded Age, American voters outside California showed extraordinary loyalty to their political parties. By contrast, enough California voters split their tickets between the two parties or changed party commitments between elections that they produced constant partisan turnover. Theodore Hittell, who published an extensive history of the state in 1897, emphasized that this pattern was virtually without parallel in other states, and he attributed it to the “‘thinking-for-itself ’ character of the people.”

Political Realignment in the 1890s

This “thinking-for-itself character” of California voters became even more pronounced in the 1890s. The elections of 1890 provided a catalyst for change. In San Francisco, the usual large Democratic majorities failed to materialize, giving the governorship and control of the legislature to the Republicans. Control of the legislature was important, because Stanford’s term in the U.S. Senate was ending, and the legislature was to choose his successor in 1891. Claiming that Buckley had sold out to Stanford, reform-oriented Democrats campaigned to oust the boss. A grand jury investigated Buckley on charges of bribery. Beleaguered, the boss debarked on an extended foreign tour, and his organization fell into disarray.

The legislative session of 1891 that reelected Stanford to the Senate exhibited such shameful behavior that it became known as the “legislature of a thousand scandals.” For example, when Senator Hearst died and the legislature had to elect someone to complete his term, a wastebasket was found filled with empty currency wrappers and a list of assembly members. Nonetheless, the legislature approved the Australian ballot, a change that drew support from reformers, organized labor, and the WCTU. Henceforth, the government printed and distributed ballots that included all candidates, and voters marked their ballots in secret.

During the early 1890s, many Americans questioned existing political and economic systems. In Looking Backward: 2000–1887, a novel by Edward Bellamy, a young Bostonian is hypnotized in 1887 and awakens in 2000 to find that all people are equal, poverty and individual wealth have been eliminated, and everyone shares in a cooperative commonwealth. Bellamy’s admirers formed Nationalist Clubs to promote a cooperative commonwealth—an economic system based on producers’ and consumers’ cooperatives rather than on wage labor and profits. As the San Francisco Examiner noted in 1890, “California seems to have an especially prolific soil for that sort of product.” California claimed 62 Nationalist Clubs in 1890, about a third of all those in the entire country, with some 3,500 members. Within a year, however, the movement had virtually disappeared, with many of its adherents swept up in the emergence of the new Populist Party.

Between 1890 and 1892, a new political party emerged, taking the name People’s Party, or Populists. Growing out of the Farmers’ Alliance (an organization similar to the Grange), the new party appealed to hard-pressed farmers in the West and South. In their 1892 national convention, they declared that the old regional lines of division between North and South were healed. The new division, they proclaimed, was between “producers” (farmers and workers) and “capitalists, corporations, national banks, rings [corrupt political organizations], trusts.” Among other changes, they called for government ownership of railroads.

Californians organized a state Farmers’ Alliance in 1890, later than in the Midwest or South. Nonetheless, by late 1891, the California Alliance claimed 30,000 members and launched a state party. California Populists attacked railroads, especially the SP, and railroad influence over politics. In 1892, Populists took nine percent of the vote in California for president and won one congressional seat and eight seats in the state legislature. They did especially well in rural areas, where farmers were suffering from low crop prices. In the 1893 legislative session, one Populist voted with the Democrats to elect Stephen White to the U.S. Senate. White, a Democrat from Los Angeles, built a political following by his relentless attacks on the SP and on corporate control of politics. Now led by White, California Democrats took the governorship in the election of 1894, but lost nearly everything else. In 1894, the Populist candidate won the office of mayor in San Francisco with his strongest support in working-class parts of the city, and the next year a Populist was elected mayor of Oakland.

The 1896 presidential election took place amidst a serious economic depression. Republicans nominated William McKinley of Ohio, a staunch supporter of the protective tariff, as the means of bringing economic recovery. The Democratic candidate, William Jennings Bryan, argued for bringing recovery by counteracting the prevalent deflation (falling prices) through an expanded currency supply. The Populists also endorsed Bryan. Bryan carried nearly all of the West and South, leaving McKinley with the urban, industrial Northeast and the more urban and industrial parts of the Midwest. McKinley also won California, though by the narrowest of margins. Thus, California behaved politically more like the Northeast than like the rest of the West.

In 1896, California and the nation stood at the beginning of a long period of Republican dominance of politics. Between 1895 and 1938, no Democrat won the California governorship, and Republicans typically controlled the state legislature by large margins. In 1896, California was on the verge of becoming one of the most Republican states in the nation.

California and the World: War With Spain and Acquisition of the Philippines

In April 1898, the United States went to war with Spain. Most Americans—and most Californians—responded enthusiastically to what they understood to be a war undertaken to bring independence and aid to the long-suffering inhabitants of Cuba, the last remaining Spanish colony in the western hemisphere. When President William McKinley called for troops, nearly 5000 Californians responded, forming four regiments of California Volunteer Infantry and a battalion of heavy artillery.

Many people were surprised when the first engagement in the war occurred in the Philippine Islands–nearly halfway around the world from Cuba. On May 1, Commodore George Dewey’s naval squadron steamed into Manila Bay and quickly destroyed or captured the entire Spanish fleet there. (Dewey’s flagship, the U.S.S. Olympia¸ had been built in San Francisco’s Union Iron Works.) Dewey’s victory focused attention on the Philippines and on the Pacific more generally. One regiment of the California Volunteer Infantry and part of the California heavy artillery were dispatched to the Philippines. They encountered not Spanish resistance, but opposition from Filipinos, who preferred independence to American control. Several Californians died in action against the Filipino insurgents.

Many Americans now looked to the Hawaiian Islands as a crucial base halfway to the Philippines. Congress approved the annexation of Hawai‘i on July 7, 1898. At the war’s end, among other settlements, Spain ceded Guam and sold the Philippines to the United States. Soon after, the United States signed the Treaty of Berlin, acquiring part of the Samoan Islands. Some Californians opposed acquisition of the Philippines out of principled opposition to imperialism, and others, especially labor leaders, opposed it out of fear of an influx of Asian labor. Other Californians, however, embraced the new acquisitions and eagerly anticipated extending their entrepreneurial activities to the new Pacific empire.