2.3: Establishing Presidios and Pueblos

- Page ID

- 126947

Throughout the western hemisphere, the Spanish king and his advisers laid down the policies and directions that guided conquest and colonization. The underlying premise was that the unsettled lands were the property of the king and that the native peoples were his subjects. Individual Spaniards were not entirely free to explore or settle where they wanted. The settlement of towns and military outposts was subject to approval, planning, and regulation. Guidelines were articulated in a number of decrees and laws, the most influential being the Recopilación de Leyes de las Indias in 1680. Despite these regulations, the frontier settlers often did not follow the laws to the letter.

Captain Gaspar de Portolá, commander of one of the first expeditions sent to colonize California, had specific orders to found a presidio at Monterey Bay. In 1769, he marched north from San Diego into new territory with only 12 soldiers and a contingent of Baja California Indians. The ship San Antonio was to meet them in Monterey with Father Serra and others. As they passed through southern California, the natives were friendly and curious. In July, they experienced a violent earthquake near the Santa Ana River and noted the richness of the grasslands in the Los Angeles basin. Portolá’s land expedition stayed along the coast but had to cross the coastal range north of San Luis Obispo. They finally saw Monterey Bay, but Portolá did not recognize it from

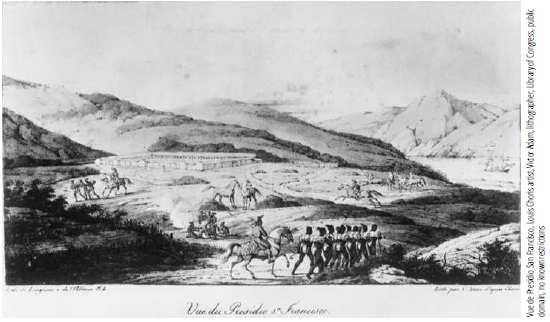

A lithograph of the San Francisco presidio, made from a water color drawing by Louis Choris, an artist who accompanied a Russian voyage around the world. The farthest northern presidio in California, San Francisco had yet to develop as a civilian settlement.

previous descriptions, so he pushed further north. Finally, a group led by Sergeant José Francisco de Ortega, Portolá’s scout, stumbled upon San Francisco Bay, viewing it for the first time from a hill. A few months later, in May, Portolá founded the presidio of Monterey, south of San Francisco, and built a wooden stockade and shelters for the troops. Father Serra, who had arrived in Monterey by ship, organized the construction of a mission called San Carlos Borromeo near the presidio and on June 3, 1770, they formally dedicated both structures.

As was true throughout Latin America, the mission and the presidio were the first undertakings in the Spanish colonization of new territories. These were soon followed by the founding of civil settlements or pueblos, forming a threepronged strategy for settlement policy. In California’s first settlement in San Diego, the most immediate need was for more provisions and for reinforcements. Due to diligent lobbying by Father Serra, who returned to Mexico City after the founding of the presidio at Monterey, the government sent other expeditions to California to strengthen the tiny settlements. The new viceroy, Antonio de Bucareli, was receptive to pleas for more support because he had evidence of Russian and British interest in California. In 1773, he issued a reglamento, a statement of how the new colony should be administered. This document was later slightly modified and reissued by Felipe de Neve, the newly appointed governor of California. Known as the Neve Reglamento, this document served as the guide for the administration of the colony until the end of the Spanish period (1821). It emphasized the importance of the conversion of the natives and the establishment of missions, of careful planning in laying out towns, of careful record keeping, and of regular supply ships from Mexico. Bucareli suggested the secularization of the missions and foresaw that they would become the center for towns.

The same year that he issued the Reglamento, Bucareli gave permission for Captain Juan Bautista de Anza, an important frontier soldier and explorer, to open a trail between Spanish settlements in southern Arizona and California and ordered him to establish a presidio on San Francisco Bay. The next year, Anza succeeded in leading an expedition of 20 soldiers and 200 livestock over the desert trails from Tucson to the mission at San Gabriel and then north to Monterey. In 1775, Anza led another expedition with more than 240 colonists making the 1500-mile journey, during which eight babies were born and there was only one death—a woman who died in childbirth. Most of the settlers went on to Monterey and a contingent helped establish a new presidio. Unfortunately, due to political conflicts with Lieutenant Governor Fernando Rivera y Moncada, Anza was not able to lead the final expedition to settle San Francisco himself. So, on September 17, 1776, Lieutenant José Moraga and Fathers Francisco Palou and Pedro Cambón founded the presidio and the mission of San Francisco.

The Spanish government decided to found civil towns in California primarily as agricultural centers to provide food for their presidios. The mission fathers had resisted having the presidio depend on the mission for supplies. Three official pueblos were eventually founded in California during the Spanish era: San José de Guadalupe (San José), El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Angeles del Río de Porciúncula (Los Angeles), and the Villa de Branciforte (Santa Cruz). Following long-established Spanish customs of town planning, the viceroy allowed the settlers certain rights, among them the right to elect a town government to regulate matters of daily life and the right to hold private property or town lots. Each pueblo was given a grant of land to be administered by the local government for the common good. Usually this grant approximated four square leagues, or nearly 20 square miles, a size that included not only a village but also surrounding agricultural lands.

The civil settlements in California were populated by settlers drawn from the local presidios as well as from special colonizing expeditions. In 1777, the California governor, Felipe Neve, authorized 14 men and their families to leave the presidios of Monterey and San Francisco to found the pueblo of San José. And in 1781, Neve authorized a colonizing expedition of 12 settlers and their families from Sinaloa to settle near Mission San Gabriel in southern California near Yangna, an Indian village. This was the pueblo of Los Angeles, founded on September 4, 1781, by a group composed mostly of mulatto and mestizo families. Branciforte was the last town founded in the Spanish period, and the least successful. In 1796, the government tried to recruit retired soldiers from Mexico to live in the new town, but no one wanted to go north to the forbidding lands of Alta California. Finally, the government recruited convicts and their families and forced them to settle the new town, but it did not flourish.

It may seem strange to us today that more Mexican colonists did not go north to California during the Spanish and Mexican periods. This lack of largescale movement was attributable to a number of factors. First, there was a cultural predisposition to prefer urban life to life in the hinterland. The vast majority of the Mexican population was not free to move about and live where they wanted. Spain and then Mexico tried to control and regulate the movement of people away from the metropolitan center. Second, most people in Mexico had developed deep ties to their extended families and regions and were reluctant to abandon their homes for the dangerous unknown territory to the north. There was widespread ignorance of the resources and climate of the north in addition to stories of Indian attacks, gruesome deaths, and massacres on the northern frontier. Finally, it was not easy to travel to California overland from Mexico. Settlers had to traverse the Sonora and Mojave Deserts, which were controlled by unfriendly Indians. The cost of travel for most Mexicans was prohibitive unless the government subsidized the expedition. Similar barriers worked to prevent a large-scale migration of settlers to other regions north of Mexico.

Spain gave fewer than 20 land grants to individuals during its rule of California—all to ex-soldiers, as a reward for their services. Most of the good land was reserved for the missions, and it was not until the Mexican period (after 1821) that private land grants became common.

The civilian settlers in the three Spanish towns relied primarily on agriculture and stockraising for their living. To assist them in their labors, they borrowed Indian neophytes from the nearby missions and also employed local gentiles, or unbaptized Indians. The government tried through regulation to limit exploitation and corruption, but this was largely ineffective. The employment of mission Indians in the towns was so popular that it seriously threatened the mission fathers’ conversion efforts. Without California Indians working in the fields of the town lands, the Spanish pueblos probably would have failed.