2.2: Demographic and Ethnic Growth of California

- Page ID

- 126946

The demographic and ethnic growth of the new Spanish outpost shows a society composed mainly of unmarried males of diverse ethnicity. Historians have had difficulty determining with certainty who these individuals were. For a decade San Diego was a transient presidio with very few of the soldiers remaining very long—a foreshadowing, perhaps, of the military future for San Diego. The leaders of the founding expedition, Fathers Serra and Crespi and Captain Portolá, were Spaniards. This has led some to suppose that the whole expedition was composed of fair-skinned Spanish conquistadors. Notwithstanding the practical impossibility of determining the ethnicity of the surviving soldiers, there is evidence to suggest that the majority of them were probably of mixed blood—mestizos and mulattos.

The Spanish developed a complex system of classifying various mixtures of European, African, and Indian parentage. A caste system was used to exclude non-Iberians from higher political and economic posts and to create a stratified society along racial and economic lines. On the far northern frontier, however, ethnic distinctions blurred and became more fluid. In California there was a great division between the gente de razón (literally, people of reason), meaning those who were Catholic Christians and European in culture, and those sin razón (without reason), the nonconverted native people. A great premium was given to those Spaniards who could prove their limpieza de sangre, or “purity of blood,” meaning there was no intermarriage with Jews, Moors, or other non-Christians in their ancestry. Often, people with wealth were able to purchase papers certifying that their bloodlines were pure and European, thus elevating them within the caste system.

Hubert Howe Bancroft, a historian of California’s pioneers, thought that most of the settlers in California were “half-breeds.” Nevertheless, in the late 19th century, Americans came to think of the first Spanish-speaking settlers as Spaniards. Los Angeles’s founding families, however, are an example of the importance of the non-Spanish-born settlers. Of the 11 male heads of households who were among the founders of Los Angeles in 1781, only two were Iberians; the others were a multiethnic group that was predominantly Indian, mulatto, and mestizo. Historians have found that a large number of Spanish speaking colonists throughout the Southwest were not Iberian Spaniards at all but rather of mixed blood, castas, and Hispanicized Indians, most of whom had migrated from adjacent Mexican frontier provinces. The first evidence we have of the ethnicity of the surviving colonists in the presidio of San Diego, for example, is the Spanish census taken in 1790, which counted 190 persons. Of the 96 adults, 49 were españoles, but only three of those had been born in Europe. The rest had probably been “whitened” (on the frontier, people could “pass,” depending on their wealth and occupation) to meet Mexico City’s requirements that most of the soldiers be español. The census listed the balance of the soldiers as mulattos and colores quebrados (some African ancestry), mestizos and coyotes (degrees of Indian–Spanish mixture), and indios.

Whatever the ethnicity of the settlers and colonists who came to Alta California from Mexico, their numbers grew slowly. Mestizaje, or the mixture of races and cultures, began in Mexico with the conquest and continued on the far northern frontier. Soldiers married local Indian women, and female immigrants who came to California were mostly mestizo or mulatto. By 1800, some 31 years after the initial settlement in San Diego, the total Spanish-speaking population in California, excluding the mission Indians, priests, and soldiers, was probably about 550 people in about 100 families. This small group lived in three pueblos surrounded by perhaps as many as 30,000 mission Indians. Meanwhile, the vast majority of native peoples remained free of the mission system and never accepted Spanish domination.

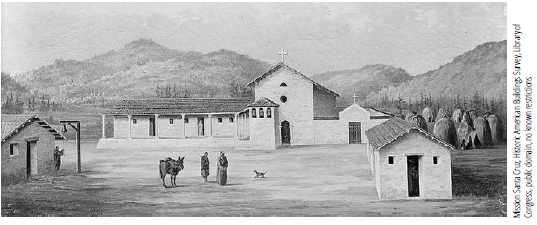

The Missions

Without a doubt, the most important Spanish institutions in Alta California were the missions, for they changed the way of life for thousands of native people and formed the economic backbone of the province. The object of the missions was to convert the natives to Christianity as well as to Hispanicize them, instructing them in the rudiments of the Spanish language and culture. After a period of time, specified in the Law of the Indies as 10 years, the missions were to be secularized or disbanded and the mission Indians were to form new towns and be converted into loyal farmers and ranchers. In this way, the Spanish hoped to extend their control over all of California. This was the ideal, but in fact, after the 10 years, the mission fathers concluded that the Indians were not able to make the transition and they postponed freedom for their charges again and again. The final objective was to turn the Indian people into Christian laborers, who would be loyal to the Spanish crown and capable of defending themselves against intrusions by hostile Indians and foreigners.

Beginning with the first mission at San Diego, Father Junípero Serra labored to found as many missions as possible. Serra was one of a generation

of frontier priests who combined extremes of asceticism and self-denial with practical political sense and a fighting spirit. He was born on the Spanish island of Mallorca to poor parents who sent him away to a Franciscan school where, because of his intelligence, he was encouraged to become a priest. When he was only 24, he was appointed professor of theology and for five years he taught at distinguished Spanish universities. In 1749, he gave up his prestigious career to travel to Mexico. Arriving in Vera Cruz, he insisted on walking the hundreds of miles to Mexico City, an act of willpower and commitment that he repeated many times in his life. Serra worked among the Indians in Mexico as a missionary and an administrator of the College of San Fernando. In 1767, the Jesuits were expelled from the New World and Serra was chosen to administer the missions they had built in Baja California. A few years later, despite being an asthmatic and suffering a chronic leg injury, Serra traveled north to lead the founding of new missions in Alta California. For the rest of his life he suffered from scurvy and from exhaustion due to walking hundreds of miles. He also practiced many mortifications of the flesh, such as wearing shirts with barbs, self-flagellation, and self-burning, in order to purify his spirit.

Father Serra established San Carlos Borromeo, the mission at Monterey, which was later moved to the Carmel River. He also founded the missions of San Antonio de Padua, San Gabriel Arcángel, San Luís Obispo de Tolosa, San Francisco de Asís, San Juan Capistrano, San Buenaventura, and Santa Clara de Asís. After Serra’s death in 1784, Father Fermín Francisco de Lasuén labored from 1785 to 1803 to complete the construction of nine more missions. The last one to be established in the Mexican era was founded in 1823, after his death. Together, the missions totaled 21, each one about a day’s ride apart and strategically located near the coast. Father Lasuén was a gentle and refined man who was wholly devoted to the memory of Father Serra. Besides building

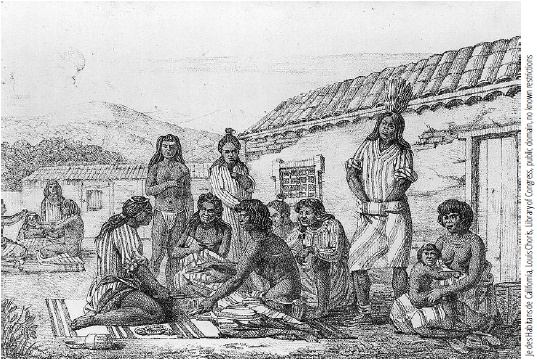

A group of Indians, possibly Ohlone, playing a game at a mission near San Francisco

new missions, Lasuén expanded and rebuilt older mission buildings, and under his diplomatic guidance the missions system prospered, experiencing less conflict with the military and government than had been true under Serra.

The conversion of the Indians was not easy. From the beginning, the natives who were to be missionized were not willing participants in this project. At first, the harvest of souls was alarmingly meager. After its founding, a year passed at Mission San Diego before the first convert was made. This was followed by several revolts against the mission padres (fathers, or priests). At the missions located near a presidio or a pueblo, there were frequent problems between the native people and the soldiers or civilians. The priests often complained of the corrupting influence of Spanish ways. Rapes of Indian women were a frequent source of conflict, causing many of them to flee into the backcountry to get away from the Spaniards. As a result, Serra moved two missions, San Diego and Monterey, farther away from their nearby presidios.

Conversions occurred nevertheless, because the Spanish priests offered food and goods that the native people found valuable. Ethnohistorians have argued to what degree environmental factors influenced their conversions; periodic droughts, along with the destruction of native plants due to grazing of cattle, pigs, and other livestock, pressured some Indian communities to seek the relative security of mission food stores. There were other complex reasons for their baptism. Often, the natives came to the missions out of curiosity and were converted without fully understanding the import of their actions. Once baptized, they were called neophytes and were subject to the authority of the padre, who began to regulate their lives to lead them toward becoming a full member of the Christian community. If they ran away, soldiers were sent to hunt them down, bring them back, and to help in their punishment. Sometimes the soldiers seized any Indians they could find—whether they were runaways or not. Once the mission reached a critical mass, having enough neophytes to farm surpluses and raise cattle, the mission became a magnet for those who needed food, and conversion to Christianity was a way to ensure survival.

In this way, the 21 missions slowly grew in size and economic importance. During the 65 years of their existence, the fathers baptized 79,000 California Indians. The most populous and prosperous of the missions were those in southern California, including San Gabriel and Mission San Luis Rey. The missions produced the bulk of the province’s food used to feed the colonists and soldiers. The natives were taught to grow wheat, corn, barley, and other grain crops, to cultivate grapevines and olive orchards, and to raise cattle and other livestock. The mission fathers trained some neophytes as artisans—shoemakers, gunsmiths, carpenters, blacksmiths, and masons. Others learned to weave textiles, make candles, and tan hides. The fathers taught their charges European instruments and music, and Indian choirs and orchestras performed religious music for special masses and fiestas. The mission Indians were responsible for tending the vineyards, fruit orchards, and wheat fields, and for raising thousands of cattle and horses.

The work regime at the California missions followed a strict timetable, including morning and evening prayers and the segregation of workers by sex. Workers were overseen by Indian mayordomos (overseers) and alcaldes (leaders). Neophytes worked six days a week for five to eight hours a day. Roll call was taken at every meal and those shirking their duties were punished by imprisonment or whippings. As Pablo Tac recalled, the Indian mayordomos were there “to hurry them if they are lazy … and to punish the guilty or lazy one who leaves his plow and quits the field.…” At night, the unmarried women and sometimes the men were locked in dormitories. At some missions, neophytes were allowed to return to their villages for short durations to gather supplemental foods, but they were expected to return for mass and for work when needed.

The padres controlled the allocation of food, rationing it according to their judgment of the economic needs of the mission and those of their charges. An interrogatorio, or questionnaire, sent from Mexico City in the early 1800s asked the mission fathers a series of questions, one about the diet of the mission Indians. The answers—while allowing for the padres’ desire to make conditions appear favorable—reveal the diversity of the missions. Father Martinez at Mission San Luis Obispo stated that he gave his workers three meals a day: atole (a corn gruel) in the morning, pozole (a soup of wheat, grains, and meat) at noon, and at night another serving of atole. At Mission San Buenaventura, Father José Señán stated that he gave the Indians one meal a day, “inasmuch as when they work they also eat.…” Other missionaries testified that the Indians continued gathering their traditional foods, which supplemented the mission food supply.

Neophyte Resistance

For many native Californians, the missions were not a positive experience. They were coerced into working and staying against their will, fearing punishment if they ran away. The most dreadful consequence of their stay was their exposure to European diseases, which often proved fatal. They had no resistance to chickenpox, measles, smallpox, and influenza, and deaths mounted with each passing year, even in areas far from Spanish settlements. Venereal disease was especially deadly; thousands of mission neophytes died from syphilis and gonorrhea, and the epidemic spread to non-mission Indians as well. The strict regulations, humiliation, punishments for minor offenses, and rapes of women by soldiers engendered a smoldering resentment of the Spaniards. Often, a chief grievance was the lack of food. The strict discipline of the mission fathers and the destruction of the indigenous food sources by cattle, sheep, and horses created levels of starvation at some missions. Conditions were such that the numbers of runaways increased and in some cases there were rebellions.

The first uprising was at Mission San Diego only six years after its founding. On November 4, 1775, around midnight, an estimated 1000 Kumeyaay Indians attacked the mission and burned most of it to the ground, killing Fathers Luis Jayme and Vicente Fuster, who became California’s first martyrs. The survivors of the first attack took refuge in an adobe storehouse, where they held off the Indians until dawn. They were finally rescued by a group of loyal neophytes and Baja California Indians. The uprising apparently came at the instigation of two brothers, Carlos and Francisco, both newly baptized neophytes who had been punished for stealing a fish from an old woman. Carlos was the chief of the local ranchería. Resenting their treatment by the padres, they ran away from the mission and began to organize an uprising of the surrounding rancherías. When they learned that about half the presidio garrison had been sent north to San Juan Capistrano, they saw this as their chance to wipe out the Spaniards once and for all. In the Spanish investigation that followed, some accused the resident neophytes of helping the attackers, but they denied it, insisting that they had been forced to go along with the uprising.

In the years that followed, there were other rebellions. In 1781, Quechan (Yuman) Indians attacked the two missions that had been built on the California side of the Colorado River. The attack occurred when Captain Fernando de Rivera y Moncada and a party of colonists bound for California were passing

through. Rivera’s troops had abused some of the Quechan peoples, and the

distribution of gifts was considered inadequate. The natives attacked, destroying

both missions and killing four friars, 30 soldiers, and Rivera himself. The

massacre ended all further land travel between Mexico and California during

the Spanish period.

In 1785, at Mission San Gabriel, a woman named Toypurina, along with three other native men, planned to lead a group of indios bárbaros (nonmission Indians) from six surrounding villages and join with neophytes to overthrow the Spanish authorities. The soldiers learned of the planned rebellion, however, and arrested the leaders. Put on trial, Toypurina explained her motivations saying, “… I am angry with the padres, and all of those of the mission, for living here on my native soil, for trespassing upon the land of my forefathers and despoiling our tribal domains.” Toypurina was banished to Monterey, where she eventually was baptized and married a presidio soldier.

During the Mexican period, a major rebellion took place among the Chumash peoples on the eve of the secularization of the missions, in 1824. The cause of this rebellion was the mistreatment of the neophytes by the soldiers and the strict work regime. Thousands of neophytes allied with gentiles (unbaptized Indians) from the interior and took over La Purísima and Santa Ynez missions for more than a month, and briefly occupied Mission Santa Bárbara. After a battle in which the padres tried to prevent needless slaughter, the rebels fled to the interior. Later, Father Vicente Sarría, accompanied by troops led by Pablo de la Portilla, convinced remnants of the Santa Bárbara rebels to return.

In October of 1828, with the permission of the priest, Padre Duran, an Indian alcalde named Estanislao led scores of his fellow kinsmen away from Mission San José to the interior to help his community harvest acorns, nuts, and other foods. Once there, Estanislao notified the Spanish authorities that they were in rebellion. He was soon joined by hundreds of other runaways from the northern missions. Estanislao’s success in resisting the Spanish government was undoubtedly due partly to the fact that natives from many different groups could now communicate with each other using a lingua franca—Spanish. For a time, Estanislao defeated the expeditions that were sent to subjugate him, until he finally succumbed to Lt. Mariano G. Vallejo’s expedition. Eventually Estanislao escaped, returned to Mission San José, and received a pardon for his rebellion. He died a few years later, working as an auxiliary soldier who hunted runaway neophytes. The Estanislao rebellion created tremendous fear among the Spanish settlers in Alta California. As a result of his movement, a network to assist runaway mission Indians grew up and Indian raids on settlements from San Gabriel to San José increased.

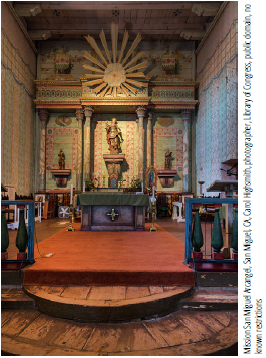

Historian James Sandos has noted that there were a variety of other forms of resistance to the mission system, ranging from graffiti secretly scrawled on mission walls, to reports of sacred visions urging natives to renounce their

Indian artisans produced the wall and decorative art at Mission San Miguel and other ALta California missions, incorporating their own cultural aesthetic into their creations. Can you find evidence of this in the photograph?

Christian baptism. George Harwood Phillips, an expert on California Indian resistance, has noted that the stations of the cross painted by neophytes at Mission San Fernando depicted Indian alcaldes as the tormentors of Christ—a subtle message of protest. Other methods of resistance included running away, abortion, and secret retention of traditional customs, such as the use of the temescal. In a few cases, the mission Indians were moved to kill the mission priests, as in the assassination of Father Andrés Quintana at Mission Santa Cruz in 1812.

Evaluation of the California Missions

In the 1980s, devoted Catholics intensified a campaign to canonize Father Junípero Serra as a saint. Immediately, a debate ensued over the record of the treatment of the natives in the missions. Native American activists, in particular, felt outrage that people wanted to honor the man who, they argued, led in the enslavement, mistreatment, and death of their people. They assembled evidence of mistreatment in the form of oral testimony by native peoples. Tribal councils passed resolutions opposing canonization, and academics wrote position papers buttressed by historical quotes and evidence arguing that Serra should not be honored. The issue of the California Indians’ encounter with the Spanish is heated, provoking spirited and emotional defense of Serra by non-Indian scholars and Catholic leaders. Beatification is a long process, and Serra has advanced through the preliminary steps. The uproar over this issue demonstrates that the mission period is still very controversial in the lives of people today.

The treatment of native peoples is a major point of debate about the Spanish colonization of the Americas. A wide range of historians and anthropologists as well as Indian activists agree that the mission system throughout the Southwest, whatever its rationale at the time, resulted in the deaths—nearly all unintentional—of thousands of native Americans. The mission system in California was perhaps the most extensive, long-lived, and destructive of all those established in the Spanish and Mexican frontier. The missions in Texas were abandoned after a short period. The ones in New Mexico provoked a violent, successful rebellion in 1680 that curtailed missionary activities until the Spanish reconquest in 1692. In Arizona, the missions were few and scattered. But in California, the 21 missions and their asistencias (branch missions) significantly changed the economy and lifestyle of those who were mission laborers as well as the way of life of those who lived far from the missions.

The Indian population declined. The natives were concentrated in missions, exposed to new and fatal diseases, and deprived of their traditional foods. The extent of the decimation can only be estimated. In California, the missions grew to include about 20,000 neophytes at their peak. The mission annals from 1769 to 1834 recorded 62,600 deaths but only 29,100 births. Anthropologist Sherburne Cook and historian Albert Hurtado have estimated that the Indian population of California decreased by more than 150,000 during the mission period. In the region where missions were established, the decline of the population was more noticeable; almost 75 percent of the native peoples died.

Defenders of the missions point out that the mission fathers did not intend to expose their wards to fatal diseases and that their attitudes toward crime and punishment were a product of the age, not especially cruel for that time. Some martyred friars willingly sacrificed themselves rather than kill natives who attacked them. Father Serra and other priests advocated forgiveness and pardons for those who ran away, although the military frequently exacted their own punishments for this offense. The priests, however, were not saints and even Father Serra was willing to admit that “in the infliction of the punishment … there may have been inequalities and excesses on the part of some Fathers.” Yet the mission priests’ religious devotion to the task of conversion and the spiritual welfare of their flock was beyond question. Their attitudes and beliefs were a product of their historical culture, in which the soul was considered more important than the body and severe punishments were the norm. Taken as a group, the mission fathers were not vicious for the times in which they lived. The tragedy was that they were helpless to prevent the deaths of the very Indians they sought to save.

The missions accomplished a great deal in developing the first agricultural economy in California. The first citrus trees, grapevines, corn, beans, wheat, barley, and oats came with the mission fathers. They promoted the raising of horses, cattle, pigs, goats, and sheep. The mission economy became the backbone for the development of large ranchos in the Mexican era and farms in the American era. The mission fathers trained the Indians to be vaqueros—farmers and skilled workers. As a result, the Indian work force became crucial to the development of California’s economy through much of the 19th century.

Nevertheless, we must also consider the missions from the point of view of the native Californians. The mission records themselves help us appreciate their grievances. Large numbers of neophytes ran away from the restrictive controls of the padres—an obvious indication of their dissatisfaction with the mission. By 1817, Mission San Diego had 316 runaways, the second largest number in the system, topped only by Mission San Gabriel, with 595. Running away was often provoked by hunger and by the corporal punishments that were administered by the mayordomos under the direction of the padres. Despite glowing reports of mission prosperity chronicled by the mission padres, death, disease, and hunger were daily realities of mission life. Deaths from disease were often hastened by malnutrition. Despite the abundance, the neophytes who worked to make it possible were badly fed. The hunger of the Indians was not limited to the missions. The introduction of European livestock and plants soon took over key hunting and gathering grounds and there were severe punishments for poaching. Hunger drove non-mission Indians to seek employment and food by working for the pueblo dwellers and for the presidio garrisons.