2.4: Gender Relations in Spanish California

- Page ID

- 126948

The first expeditions of explorers and settlers to San Diego in 1769 did not include women, but it was evident to Spanish authorities that women would be essential for the long-term success of the colonization effort. Antonia I. Castañeda, Gloria Miranda, Rosaura Sánchez, and others have written about the important role women played in this period of California’s history. In general, they have reported that Spanish and Mexican women were severely limited by the patriarchal values of their society, but they also retained a degree of protection and autonomy. Indian women, however, were more likely to be victims of

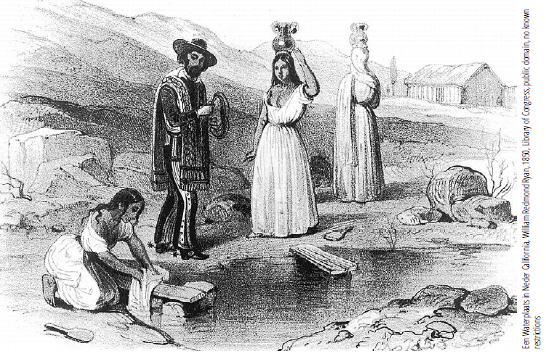

Mestizo women washing clothes and carrying water jars on their heads as a well-dressed male stands by watching them. What does this image suggest about the intersection of class/caste and gender roles in Alta California?

the early male-oriented exploration and conquest of California than Spanish and Mexican women were.

Following their experience in central Mexico, the mission padres sought to eliminate Indian customs and attitudes toward sexuality that conflicted with Catholic doctrine and morals. Accordingly, the priests severely punished women for sexual misconduct. For example, at Mission San Diego, one native woman miscarried, and then was charged with infanticide and forced to endure humiliating punishments. The priests encouraged neophyte women’s fertility, since all children were to be born into the Christian faith. At the same time, however, the priests outlawed Indian dances, ceremonies, and songs that were part of their fertility ritual. Women who refused to comply were sometimes accused of being witches.

Males in the secular population, especially the soldiers, often raped Indian women. This became a source of conflict between the Spanish and the native Californians. Rape, as analyzed by historian Antonia Castañeda, was more than a personal act of lust. It also was a means of subjugating the native population and expressing the power of the male colonizer over the colonized, both male and female. It served to humiliate and subjugate the Indian men and families.

A few Spanish colonists settled down and established families with Indian women. Initially, a small number of soldiers married native women at the encouragement of the priests. Castañeda found that, in the 1770s, 37 percent of the Monterey presidio soldiers married local Indian women, but, for the entire period, the intermarriage rate was just 15 percent. In order to reproduce the culture of the mother country, women from Mexico were necessary, and it therefore became a priority to import female colonists.

Non-California Indian women either came with their husbands from Mexico in the various expeditions or alone, as was the case with María Feliciana Arballo, who traveled to California with her two children in the Anza expedition of 1775. Additionally, in 1800 the government sent a group of 10 girls and nine boys who were orphans to California, where they were distributed among families already there. The girls, with one exception, were married within a few years. Gloria Miranda has studied women in Spanish Los Angeles. She found that almost all the marriages were arranged, and at a tender age—13 was the youngest age at marriage, while the average age in the pueblo was 20. Very few adult women remained single due to the overall scarcity of women. The more affluent families tended to have lots of children as befitting their means. Ignacio Vicente Ferrer Vallejo, an early settler in Monterey, had 13 children. His son, Mariano Vallejo, fathered 16 children, and José María Pico, a soldier in San Diego, fathered 10 children.

Spanish colonial society was patriarchal, with the ethic of honor deeply ingrained. A man’s honor depended on his ability to control others, in particular the women within the family. The church’s doctrines and hierarchy supported notions of male domination and superiority. Yet women were able to carve out niches of respect, in part because, under colonial laws, they had property rights within marriage. The notion of community property for women was part of the Spanish codes. The idea was to protect the honor of a woman and her family of origin within a marriage.

Rosaura Sánchez has studied the narratives of Mexican California women collected by Hubert Howe Bancroft in the 1870s. Several illustrate the ways in which mestiza women in Spanish California related to male authority. One narrative is the story of Apolinaria Lorenzana, a woman who came to California as one of the orphans in 1800. She grew up in San Diego but refused to marry, working instead as a schoolteacher and then as a nurse and teacher at the mission. She earned the nickname “La Beata” (the Pious One) because of her devotion to helping Indians. During the Mexican period, she received two rancho land grants from the governor as a reward for her services. She bought a third rancho and lived an independent life from the revenues. Lorenzana’s life reveals her independence, strength of character, and dedication to her work.

Another account is that of Eulalia Pérez, who worked as a llavera, or keeper of the keys, at mission San Gabriel. Among other things, Eulalia was in charge of making sure that the girls were locked in at night in their dormitory. She also supervised and directed many of the routines of mission life: the rationing of food, the training of women as weavers, and the catechizing of the neophytes. Eulalia’s story shows a complete acceptance of the mission as a humane institution whose primary mission was to teach. Neither Pérez nor Lorenzana was critical of the treatment given to mission Indians, but rather they saw themselves as humanizing the process of acculturation.

We also have the story of Eulalia Callis, who was the wife of California governor Pedro Fages. She desperately wanted to leave the desolate California frontier and return to Mexico City. In 1785, she publicly accused her husband of infidelity and filed a petition for legal separation. She refused to accept a compromise mediated by the priests and continued slandering the governor. The authorities arrested her and, because she was a woman, kept her locked up inside Mission San Carlos Borromeo for two months. During that time she began proceedings for a divorce, but before they were completed the couple reconciled. A year later, she persuaded Fages to resign and the family returned to Mexico. Contemporary historians see Eulalia’s story as evidence of female independence and outrage in the face of patriarchy, but it also reveals that women had the right to divorce, even in colonial New Spain.

Spanish Californian Culture

During the Spanish administration of California, the military and the church were the dominant powers enforcing discipline according to the law. Civil culture existed primarily in the towns, where people were freer from authoritarian rules. Because Spain granted very few private ranchos in this period, the hacienda lifestyle had not yet developed. Spanish society was decidedly male, primarily governed by the military and the church.

The culture that the Spanish settlers brought with them from central Mexico and the adjacent northern frontier settlement was one that made family the core of society—a family that was, in theory, strictly governed by the father. Many of the families were related by marriage or by compadrazgo, godparentage. Thus the idea of family was not limited to the nuclear one—but to an extensive network of individuals scattered throughout the province. In Hispanic cultures, godparents frequently acted as surrogate parents and they expected the same respect and obligations from their godchildren as they did from their children. Hospitality was also an important value and fact of life, given the scarcity of the population and the common religion, Catholicism.

Despite the many rules governing behavior, challenges to authority were inevitable. Sexual misconduct by both men and women was punished. In the 1790s, Sebastián Alvitre of Los Angeles and Francisco Ávila of San José were punished with sentences of forced work, prison, and exile for fornicating with Indian and married women. The provincial records are full of warnings from officials about the evils and punishments of adultery and sexual impropriety. Likewise, the authorities tried, with mixed success, to regulate gambling and the consumption of alcohol.

There were no formal schools in Alta California before 1800, when Governor Borica established the first school. The school was in a public granary in San José and was taught by retired sergeant Manuel Vargas. Funding for the school came from a compulsory tax of 31 cents per pupil. Eventually Vargas was lured to teach in San Diego, where the citizens raised 250 dollars for his pay. Several other schools sprang up in San José and Santa Barbara. The primary subject was La Doctrina Cristiana—the catechism and doctrine—followed by reading and writing.

By 1820, there were approximately 3270 Spanish and mestizo settlers in California, many of them children from large families. Most of the population growth until this time had been through natural increase rather than immigration. The kind of culture that evolved was one that was deeply influenced by the native Indians. The missionized Indians did almost all the work in constructing the presidios, missions, and public works. Most of the Spanish male adult population consisted of soldiers, priests, or administrators. Intermarriage with native women and with women who came north from Mexico produced many children. The spirit of the culture remained that of a frontier outpost whose survival still depended on the authoritarian institutions of the military and the church.