3.12: Reports

- Page ID

- 73349

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)A report is a very technical document that presents information in an objective way – it’s like the polar opposite of an essay or memoir or story. No fluff. Low on creativity. Be precise.

Read the Guidelines Carefully46

If your teacher or boss gave you guidelines for your report, make sure you read them thoroughly. The prompt will give you information such as whether your report should be informative or persuasive, who your audience should be, and any issues your report should address.

- The guidelines will also typically tell you the requirements for the structure and format of your report.

- If you have any questions about the assignment, speak up as soon as possible. That way, you don’t start working on the report, only to find out you have to start over because you misunderstood the report prompt.

Report Writing Types:

Types of reports47 include memos, minutes from meetings, lab reports, book reports, progress reports, justification reports, compliance reports, annual reports, and policies and procedures. Other types of reports48 include: feasibility reports, credit reports, sales activity reports, personal evaluation reports, incident reports, financial reports, etc.

Long and Short Reports

From John M. Lannon, "Technical Communication"49:

"In the professional world, decision-makers rely on two broad types of reports: Some reports focus primarily on information ('what we're doing now,' 'what we did last month,' 'what our customer survey found,' 'what went on at the department meeting'). But beyond merely providing information, many reports also include analysis ('what this information means for us,' 'what courses of action should be considered,' 'what we recommend, and why').

"For every long (formal) report, countless short (informal) reports lead to informed decisions on matters as diverse as the most comfortable office chairs to buy to the best recruit to hire for management training. Unlike long reports, most short reports require no extended planning, are quickly prepared, contain little or no background information, and have no front or end matter (title page, table of contents, glossary, etc.). But despite their conciseness, short reports do provide the information and analysis that readers need."

How to Write a Report

To have an effective report, always follow the right procedure. You can either order a report from the experts or have a look at seven steps to excellent report writing to be an expert yourself.

- Choose the main objective – stay focused and engage the readers with clarity.

- Analyze your audience – change the data, vocabulary, and supporting materials depending on the target readers. If you understand your audience, you can add some personal touch and suit the preferences of particular people.

- Work on the report format – learn how to start off a report and how to finalize it effectively.

- Collect the data – add the facts, figures, and data to add credibility.

- Structure the report – use the lab write up format or read the tips of the memo and report writing to know how to arrange the elements of the report.

- Ensure good readability – make navigation easy by adding visuals, graphics, proper formatting with subtitles, and bullet points. Shorter paragraphs are better than long bulks of text.

- Do the editing – after you have prepared your draft report, revise the content twice. Keep it aside for a day or two and then work it over again to gain perfection.

Scan the report to make sure everything is included and makes sense. Read the report from beginning to end, trying to imagine that you’re a reader that has never heard this information before. A good question to ask yourself is, “If I were someone reading this report for the first time, would I feel like I understood the topic after I finished reading?

How to Write an Incident Report50

If you're a security guard or police officer deployed to the scene of an incident, writing up a detailed and accurate report is an important part of doing your job correctly. A good incident report gives a thorough account of what happened without glossing over unsavory information or leaving out important facts. It's crucial to follow the appropriate protocol, describe the incident clearly, and submit a polished report.

POSSIBLE SAMPLE INTRO:

On (date, time) reporting officer (name) was (dispatched, observing, contacted by) (to, who) (location), etc. For example, On June 21, 2016, at about 2100 hrs, reporting officer, Smith was on duty and received a dispatch call for a burglary in progress at 123 2nd St; in St. Cloud, Mn. Upon arrival, the officer observed an elephant smashing the front window glass of an electronics store, the elephant, later identified as Snout, Henry, placed a large television set in his trunk and attempted to flee the location on foot.

Steps:

- Start the report as soon as possible. Write it the same day as the incident if possible. If you wait a day or two your memory will start to get a little fuzzy.

- Provide the basic facts. Your form may have blanks for you to fill out with information about the incident. If not, start the report with a sentence clearly stating the following basic information:

- The time, date and location of the incident (be specific; write the exact street address, etc.).

- Your name and ID number.

- Names of other members of your organization who were present

- Include a line about the general nature of the incident. Describe what brought to you at the scene of the incident. If you received a call, describe the call and note what time you received it. Write an objective, factual sentence describing what occurred.

- For example, you could write that you were called to a certain address after a person was reported for being drunk and disorderly.

- Note that you should not write what you think might have happened. Stick to the facts and be objective.

- Write a first-person narrative telling what happened. Write a chronological narrative of exactly what happened when you reported to the scene.

- Use the full names of each person included in the report. Identify all persons the first time they are cited in your report by listing: first, middle, and last names; date of birth, race, gender, and reference a government issued identification number.

- For example, when the police officer mentioned above arrives at the residence where he got the call, he could say: "Upon arrival the officer observed a male white, now known as Doe, John Edwin; date of birth: 03/15/1998; California Driver's License 00789142536, screaming and yelling at a female white, known as, Doe, Jane, in the front lawn of the above location (the address given earlier). The officer separated both parties involved and conducted field interviews. The officer was told by Mr. John Doe that he had come home from work and discovered that dinner was not made for him. He then stated that he became upset at his wife Mrs. Jane Doe for not having the dinner ready for him."

- If possible, make sure to include direct quotes from witnesses and other people involved in the incident. For example, in the above scenario, the officer could write “Jane said to me ‘Johnny was mad because I didn’t have dinner ready right on time.'”

- Include an accurate description of your own role in the course of what occurred. If you had to use physical force to detain someone, don't gloss over it. Report how you handled the situation and its aftermath.

- Be thorough. Write as much as you can remember - the more details, the better. Don't leave room for people reading the report to interpret something the wrong way. Don't worry about your report being too long or wordy. The important thing is to report a complete picture of what occurred.

- For example, instead of saying “when I arrived, his face was red,” you could say, “when I arrived, he was yelling, out of breath, and his face was red with anger.” The second example is better than the first because there are multiple reasons for someone’s face to be red, not just that they are angry.

- Or, instead of saying “after I arrived at the scene, he charged towards me,” you should say “when I arrived at the scene, I demanded that both parties stop fighting. After taking a breath and looking at me, he began to run quickly towards me and held his hand up like he was about to strike me.”

- Be accurate. Do not write something in the report that you aren't sure actually happened. Report hearsay as hearsay, not as fact.

- Additionally, if you are reporting what the witness told you, you should write down anything that you remember about the witness's demeanor. If their statement's cause controversy later, your report can prove useful. For example, it would be helpful to know that a witness appeared excited while telling you what happened, or if they seemed very calm and evenhanded.

- Be clear. Don't use flowery, confusing language to describe what occurred. Your writing should be clear and concise. Use short, to-the-point, fact-oriented sentences that don't leave room for interpretation.

- Be honest. Even if you're not proud of how you handled the situation, it's imperative that you write an honest account.

Polishing Up a Good Report:

- Double check the basic facts. Check to make sure the basic information (spellings of names, the dates, times, and addresses, the license plate numbers, etc.) match those you listed in your report.

- Do not try to make sure that statements in your report match those of your colleagues. Individually filed reports guarantee that more than one account of an incident survives. Incident reports can appear later in a court of law. If you alter the facts of your report to match those of another, you can be penalized.

- Edit and proofread your report. Read through it to make sure it's coherent and easy to understand. Make sure you didn't leave out any information that should have been included. Look for obvious gaps in the narrative that you might need to fill in.

- Remove any words that could be seen as subjective or judgmental, like words describing feelings and emotions.

Submit your incident report. Find out the name of the person or department to whom your report must be sent.

EXAMPLE: REPORT ON STUDENTS

To: Wade King, Department Chair

From: Sybil Priebe, Associate Professor

Date: November 7, 2013

Subject: Report on My Students

INTRODUCTION:

This survey report shows the results of three years of my classroom grades and excuses from students.

DATES:

This survey was completed in November, during the years listed on the charts, on the campus of North Dakota State College of Science in Wahpeton, ND; this town is located 48 miles to the south of Fargo, ND.

DEFINITION OF THE POPULATION:

All of my students were used for this report. Some were in class all the time, some were not. Some might have been drunk, and some may have not been “all there,” but oh well. The approximate age surveyed was 21.5, while the span of ages ranged from 18 to 25. Forty percent of those surveyed were males; the rest were females. All students surveyed were full-time students; only 5 of the 50 surveyed were students who did not live on campus.

EXCLUSIONS FROM THE SAMPLE:

Older-than-average students and single-parents happen to not be a part of this survey’s sampling.

GOAL OF REPORT:

Through this survey, I hope to identify how students are doing in my classes.

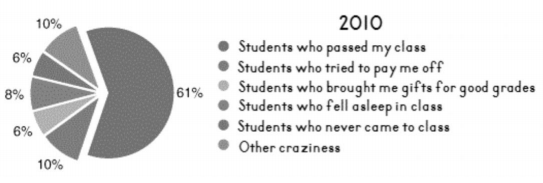

Let me first start off by explaining the options above before I compare the years. The options – ranging from “students who passed” to “students who never came to class” –were created after years of me journaling the various excused I’ve gotten from students about their efforts and attendance in class.

Let’s begin by analyzing the first option and the largest chunk of the pie chart.

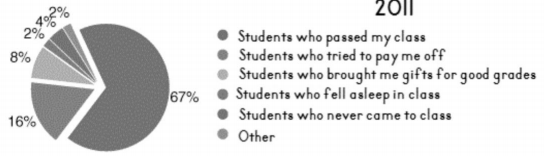

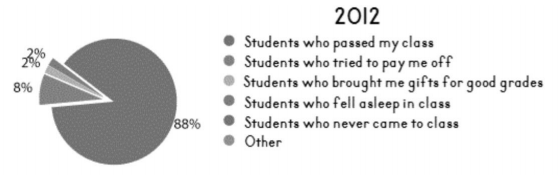

When I first started keep track of students, my pass rate was 61% which is barely passing (if one uses the 60-70-80-90 Grade Scale). One can see that in 2011, that rate bumped up a bit, and then in 2012, it dramatically increased. I can only contribute that large jump to the lack of “Other craziness” that year. “Other craziness” translates into: weather-related chaos, a rise in student illness, weird vibes in certain classes (maybe due to students being hangry), etc. In 2012, there were also a lot less students trying to pay me off for good grades, so that is obviously a side effect of students passing.

Speaking of the “pay off” option, it oddly jumped from 10 to 16% in 2011, but then chopped itself in half for 2012. I’m uncertain why there was such a jump between 2010 and 2011, but the cut from 2011 to 2012 seems to be due to the rise in passing students.

As for gifts, that percentage stayed relatively the same. Sleeping in class took a dive after 2010, and I’m unsure why (although I taught more in the late morning that year, so perhaps there’s a connection). Lastly, students who never came to class trailed off into nothing by 2012, so that’s reassuring.

OVERALL FINDINGS:

This report has shown me all sorts of variety in how my students approach the class and how our surroundings can affect student learning. When there was less “craziness” on campus, students came to class and passed. Teaching late morning classes has helped keep my students awake, and when there are fewer students falling asleep or being absent, they pass as well!

Assignments or Questions to Consider

Situation: You’re a security guard or police officer deployed to the scene of an incident. Write up a detailed and accurate incident report; make sure to follow the steps in the chapter to create the best report possible.

46 “How to Write a Report.” Co-authored by Emily Listmann, MA, Education; 12 Sept 2019. https://www.wikihow.com/Write-a-Report Under an CC-BY-NC-SA License.

47 Nordquist, Richard. "What Are Business and Technical Reports?" ThoughtCo, Jun. 8, 2019, thoughtco.com/report-writing-1692046.

48 “How to Write a Report.” Co-authored by Emily Listmann, MA, Education; 12 Sept 2019. https://www.wikihow.com/Write-a-Report Under an CC-BY-NC-SA License.

49 Lannon, John M. "Technical Communication." Laura J. Gurak, 14th Edition, Pearson, January 14, 2017.

50 “How to Write an Incident Report” was co-authored by Clinton M. Sandvick, JD, PhD. Updated: May 10, 2019; https://www.wikihow.com/Write-an-Incident-Report; licensed CC-BY-NC-SA.