7.3: Modes

- Page ID

- 25408

A mode, or type, or form, is the kind of writing you are choosing to do. A mode, in writing studies, is also sometimes called a genre.

What are some modes? To take an example, you can choose to do the kind of writing that informs. This is often called expository writing, but in this book, we refer to it as informative writing. Informative writings include reports, manuals, annotated bibliographies, narratives, news reports, and descriptions.

You may also choose to do persuasive writing, which means the text you produce seeks to argue a point to convince an audience. Under persuasive writing we can include rhetorical analyses and literary analyses, which are persuasive assignments often assigned in college. You might also be asked to write a thesis-driven essay that makes a strong point and is then defended in the rest of the essay. Persuasive writing can use experience or research to support the thesis.

There are also a variety of important professional types of writing which include emails, résumés, postings on social media, cover letters, and proposals.

Other modes include proclamations, law codes, policies, deeds, manifestos, declarations, treaties, speeches, and anthologies.

Informative writing

Informative writing is not generally said to be written in order to influence an audience’s opinion. A person writes informative texts simply to provide data, or statistics, or information. Organization is very important in informative writing because often the person reading an informative text is does not need to read the entire text. They only want to find and read the information they are looking for. Examples of this would be a manual for a new iPhone, a dictionary, or an employee’s report to their boss about a new product release.

Another example of informative writing is a news report. For the most part, it lets the reader know what happened, and when, and where, and how. For example, “The college budget projections were announced Tuesday by the President in the commons room of the university.” Sometimes the reason, or cause, of what happened is mentioned, but this is not the only focus, nor is it a point of debate, in a news report. A news report, like all informative writing, is fact-centered.

In general, for informative writing, one has a very clear topic, such as “fluid mechanics” or “how a supernova operates” or “how to play tag” or “what happened at the Constitutional Convention in 1787.” Informative writing has clear definitions and is often accompanied by straightforward organization. Informative writing also sometimes includes an outline or big and bold topical headings that go before each section and subsection. This is so that the reader can very easily find the piece of information they are looking for. Detailed informative writing must be well-researched.

Informative writing: Reports

A report is a piece of writing that gives information or tells what happened. A report must be well-researched, or utilize first-hand experience. When writing a report, you can use your experience or the experience of others. A report must have a clear topic and outline. The definitions must be obvious or well-explained. Any quotations contained in a report must be accurate.

A report begins with a clear explanation of what will be contained in it. Then it moves to supporting detail. Then it concludes, often summing up the main things to be learned in the report.

Often a longer report has a “brief” or “summary” before the main report, containing all the major points that are in the main report. You can find short summary documents like this often in law, where one must have the full, detailed report available, but one must also have a summary document to give to anyone who just wants the “talking points” from the main report. This is often also called a “fact sheet”, printable as a one-page pdf or brochure that tells the main ideas of the larger document or text.

Examples of reports include data from a survey or poll, a report from a zoologist on the conditions in a certain facility, and a news report. See, the example below and notice that this example shows a writing that could also be called an essay.

Example of a report - informative writing

What I Did on My Summer Vacation

“Boom! Crack-a-lacka!” A thundercloud burst outside my window and woke up me and my teddy bear. It was the first day of summer vacation. My father’s list on the fridge was the only thing between me and freedom. I went downstairs and entered the eggy-smelling kitchen. But there was no list on the fridge!

This is how my summer vacation began, and it got better from there. My cousins and I rode horses on their farm all through the first weeks of the summer, and then we all jumped into the pickup and went to the rodeo. Have you ever seen a five-year-old boy ride a mad hog? We did. And my uncle bought us pink ice cream and pink cotton candy. We looked like hogs ourselves when we were done. But, in case you’re wondering, we didn’t throw up on the rides.

You know that feeling when August comes closer, how you can’t figure out how to pack the most amount of fun into one day? Well that feeling would not go away for me last summer, because I got a free load of books from one of my aunts, left on the porch one morning in mid-July. Well, this killed my outdoor play for three weeks, unless you count reading “Catcher in the Rye” and “The Outsiders” and “Old Yeller” in the treehouse for hours on end in the shady breezes by the brook as “playing outside.”

In August, though, my dog got sick, so we spent most of our time at the vet, or making cards to tack on the fence near his doghouse so he could see them and maybe get well faster. My sister planted a “hope garden” next to the doghouse with one sad plot of grass and two bean plants. She said that some Native American tradition she read about promised that the “hope garden” would make the dog get better faster. I didn’t believe her, but the grass looked fresh and pretty next to the fading doghouse.

Summer vacation ends, as you know, on Labor Day. I had swam, jumped, kicked, raced, and read all summer. I had two skinned knees and one skinned elbow to prove it, and six fish bone skeletons hanging on the walls in my room to prove I had fished. I won a fourth place ribbon at the local fair for my chili, and there was a green ribbon above the kitchen table to prove that. But I had no ribbon to prove our team had beat the team of the neighboring town in our baseball tournament this summer. You’ll have to just believe me on that.

In the writing process, when you are revising informative writing, you will probably focus especially on revising for accuracy of data, clarity of presentation, and organization.

Informative writing: Example of a book report

Jamal Student

English 101

Book report on Beyond Good and Evil, by Friedrich Nietzsche

Wicked Moods and Tones

In Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche adds to the philosophical conversations of the late 1800s. He discusses nature, what is natural, and the importance of psychology. But his main focus is on what he says is “morality.” In his discussion of this topic, he seeks to unchain people from old ideas of right and wrong ways to behave, and to have them be more free.

He goes through history, and mentions many movements of philosophy from Plato to the present. He seems to be arguing against quite a few of the people he mentions, holding them to be somewhat antiquated and stifling. His way of writing is so playful, however, that one can’t be entirely sure of what Nietzsche really thinks. For example, he writes, “All this goes to prove that from our fundamental nature and from remote ages we have been—accustomed to lying” (61). When he says this, does he mean “lying” in a moral sense? It is hard to know.

I enjoyed this book. I thought it was difficult to comprehend, what with all the Latin phrases, but I got enough out of it to form the judgment that it is worth reading, has some interesting ways of using language and some fascinating thoughts, and that it makes me understand modernity and the history of thought a little better.

Work cited

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Beyond Good and Evil [1886]. Dover 1997

Informative writing: Compare and contrast

A compare and contrast writing is often done as a short paper on its own, or as smaller part of a research or persuasive essay. It describes two things carefully and clearly, and then compares them, often ending by concluding which of the two is better.

A compare and contrast essay is well-organized, factual, and detailed. The style is often direct and vivid. The point is to document similarities and differences, to make people see things in a fresh way, or to gain insight. It focuses the audience’s attention in a way that makes them think.

Examples include comparing two products and concluding which is better or outlining two solutions to a contemporary or personal problem and concluding which is better. Often, when preparing to write a compare and contrast piece, the writer makes lists of similarities and differences between the two things that are being compared. The subject-by-subject, or block method of organization can be used—one describes one thing completely, and then the other, and then concludes. Or, one can go point-by-point.

Example of compare and contrast – informative writing

Mow, Wow, the Best Way to Mow

I have to buy a lawnmower. I live in the suburbs, and one must have a lawnmower when one has a lawn. But which lawnmower, that is the question. A riding lawnmower or a push mower? My lawn is only one acre, but the grass grows quickly in the summer, and I want to make the right choice.

quickly in the summer, and I want to make the right choice. A riding lawnmower is easier on the back. You don’t have to sweat as much when you ride. A riding lawnmower is big, too, and gets the job done quicker, because the wide blade is cutting so much grass per second. A riding lawnmower can also be used by all members of the household—my elderly father can even cut the grass with a riding lawnmower if he wishes to. But on the other hand, a riding lawnmower is expensive. It is also bigger, so you have to have more space in the garage to store it. It is also an attraction to children, and they could get hurt on it.

A push mower helps you get much more exercise when you use it, because you are using your arm and leg muscles a great deal as you push that mower, especially through the taller grass. A push mower can also get into littler areas, so you don’t have to go over the lawn with a weed-whipper when you’re done mowing to get all the spaces under the deck and around trees. A push mower is also small and easily stored. A push mower also has less pollution, because the engine is so small. But a push mower is also slower, so will the grass get mowed as often if I get a push mower? And with a push mower, it takes longer to do the entire lawn, because the area the blade is cutting is not very large.

I think I’m going to go with a push mower. I like the idea of getting more exercise whenever I cut the lawn. I like the cheap price. I want to help the environment. And, let’s face it, I don’t want the neighbors in my uppity suburb to think I’m lazy.

Informative writing: Annotated bibliography

An annotated bibliography is a specific kind of informative writing that is often assigned in beginning college courses. There are three elements of an annotated bibliography: the citation of an article, the summary of the article, and the connection to the topic at hand. Sometimes this last element, the connection to the topic being researched, is not included. In an annotated bibliography there is always a citation of an article. For example, you may write an annotated bibliography about three books and articles that you found about why people become psychopaths. Often, an annotated bibliography is done in preparation for writing a longer paper in which you seek to persuade.

Each entry of an annotated bibliography begins with the citation of the book or article. Then there is a brief summary of the contents of the book or article. Sometimes, the last few sentences of an annotated bibliography include a reason why the book is going to be used in a research project, or why it is important, or an assessment (value-judgment) about the book or article. Annotated bibliographies can be very brief summaries, such as in the example of an annotated bibliography below. Or they can be longer, and each entry may include a key quote or two from the book or article.

Example of annotated bibliography: Informative writing

Jade Patel

English 101

Fall 2020

Psychopathic Personality Research

My topic is crime, specifically psychopathy. So far I have three articles that I have found, which I annotate below.

1. McCuish, E. C. and R. Corrado, P. Lussier, and S. D. Hart. “Psychopathic traits and offending trajectories from early adolescence to adulthood” Journal of Criminal Justice 42.1 (2014): 66-76

In this article, the authors go through trajectory studies of adolescence who have committed crime. They categorize different types of traits and research which traits are associated with offending behavior. They make conclusions that it is the chronic individuals who appear to be the most psychopathic.

2. Kiehl, Kent, and Morris Hoffman. “The criminal psychopath: History, neuroscience, treatment, and economics” Jurimetrics 51 (2011): 355-397

In this article, the authors go through the history of the psychopathic personality. They describe the problem that psychopaths present to society. They try to increase awareness of the condition, and give information about psychopaths that is informed by history and research.

3. Millon, Theodore, and Erik Simonsen, Roger Davis, and Morten Birket-Smith (eds). Psychopathy: Antisocial, Criminal, and Violent Behavior. The Guilford Press 2002.

In this book, the editors present articles on psychopathy. They try to bring the reader up to date on what the current research situation is like in psychopathy studies. They discuss definitions and the reasons people are psychopaths, as well as how to correct and fight against the bad effects that psychopaths have on society.

Informative writing: Descriptions / Explaining a process

In writing a description, you state the place, thing, time, process, action, or person you are describing. Then you proceed to give details about it. For example, when you write a short story, you often describe the main character towards the beginning of the story; she is an engineer, tall, white-haired, and likes fishing.

A description is often a small part of a larger piece of writing. For example, in a compare and contrast paper, you describe the two things you are comparing, first one, then the other, and then you compare and contrast them. Or in an experience-based persuasion writing, you describe a situation you were in. Careful word choice and position is key to a good description.

In writing a description, keep the five senses in mind. What did it look like? Start at the top and work your way down. What did it smell like? Compare the smell to something else if you can. What did it feel like, the different parts of it? What did it sound like and taste like? And in writing descriptions, as with all writing, look at other good descriptions and model your writing on them.

Graphic: Informative versus persuasive writing

Now we have reviewed informative modes of writing. Here is a graphic to illustrate as we move to a different kind of writing, a different mode: persuasive writing.

INFORMATIVE VERSUS PERSUASIVE WRITING

An example of informative writing about marshmallow:

Marshmallows are sweet. They are white. They are often roasted over a fire. They are very soft and melt easily. Most Americans have eaten marshmallows, especially at the lake during the summer.

An example of an argument about marshmallow:

Marshmallows should be sold with warning labels. They stick to your hands when they melt when it is hot. They are also horrible for your teeth. They are high in calories too. For these and many other reasons, bags of marshmallows should come with warning labels.

Persuasive writing

Persuasive writing includes narration, rhetorical and literary analyses, definition, and experience- or research-based argumentation.

All forms of writing contain some kind of persuasion, even informative writing. For an example, a grocery list is informative writing, but the audience, the person for whom it is written, also takes it as a bit persuasive; it has the implied argument: “You should go pick these things up from the store.” Even a report you deliver to your boss informs him of what the engineering department is up to, but it also has that implied persuasion: We’re doing our job here well; our department is worth the money, and so on.

But let’s look at persuasive writing now as writing that has as its very essence and core the desire to persuade, to change minds, to move people in one direction and not another.

Persuasive writing does contain factual information that is not arguable. But, in general, persuasive writing is not about just giving information. It is meant to shift hearts, to move souls, to change opinions, to deepen thought.

Often persuasive writing is called “argumentative writing.” However, it is unfortunate that when people hear the word “argument," they think of two people screaming at each other in the kitchen, and one of them is ready to knock the other one over the head. But an argument paper is not about bad feelings and destroying the other person, or at least, it shouldn’t be. There is a technical way we use the word “argument” in writing texts, it simply means offering a written text into an ongoing debate with the hope of securing agreement among people of good will who currently disagree with you or hold a different view. This is the nature of deliberative democracy, and it is the only ethical way to do argument.

In all argument writing, or persuasive writing, you give background information, and you make a claim (thesis) and you give evidence to support the thesis. You often appeal to the interests and emotions of your audience. You keep an ethical and respectful tone. You usually entertain counterarguments. You conclude, summing up your main points.

Remember, you don't argue about things that are self-evident (such as that the sun is in the sky), but about things that can reasonably be debated, such as who will win the Super Bowl this year, or what we should do about health care in our state. You should also choose topics that people care about deeply. It depends on the audience.

Often we make a distinction between persuading by working with your reader and persuading by leading your reader. Which method you choose will depend on your audience. If you think your audience will not mind feeling as if you are controlling them, you may choose to persuade them by leading them. If you think your audience would prefer to feel as if they are participating in their movement towards a new position, you may wish to persuade them by working with them—by acknowledging them often, by reminding them what they already know, etc.

As discussed in earlier chapters, we often say that there are three methods of persuasion: ethos (persuading by means of presenting good character, credentials, or reputable sources), pathos (persuading by means of moving the emotions), and logos (persuading by means of facts and reason).

The basic outline of an argument, or persuasive form of writing, is this

- Claim (thesis) (as part of the introduction)

- Supporting reasons

- Consideration reasons

- Consideration of counter-arguments (optional)

- Conclusion and resaying of claim (thesis)

Because persuasion is so dependent on a central claim (thesis), often in the writing process you'll find that if you change your thesis, even a little, you have to go through and rework a good deal of the rest of the writing.

Persuasive writing: Definition writing

Definition writing is often parts, or sections, of other writings. Definitions are important, because accuracy of definition, or naming, is one of the greatest problems in persuasion—often people mean different things by the same word. So, especially in using big, abstract words like “justice” and “democracy” and “fair,” you need to be clear on what you mean. For example, if you write a whole paper arguing that scholarships need to be awarded fairly but never define “fair,” then your argument is founded on shaky ground. Even if you provide great evidence and reasoning, your audience can say, “But that’s not what I think fair means.”

When defining, keep in mind that there are different kinds of definitions: denotations and connotations. A denotation is the official, accepted definition. It includes both the official dictionary information (including parts of speech, forms, and alternate meanings) and commonly held definitions. For example, take the word “apple.” An apple’s denotation would include its pronunciation, the fact it is a noun, and the idea that it refers to a fruit growing on a tree in a northern climate that can be red, green, or yellow.

The connotations of a word are meanings that go beyond the denotation, that often have feelings and symbolic meanings. Take the word “apple” again. We associate so many things with apples: health (an apple a day keeps the doctor away), education (an apple for a teacher), patriotism (American as apple pie). sin (Garden of Eden), New York City (The Big Apple). You could probably think of even more.

When you define a word, be aware of its denotation and connotations. And remember, you can use connotations to lead and persuade and move your reader. For example, knowing apples are a symbol of health, you can use that in your writing to symbolize healthy living. Apples are serious, too (unlike the funny banana).

Writing a dictionary definition is not enough. For example, the definition of a “rosebud” in the dictionary is “a bud of a rose.” This is not really helpful for really explaining the object to someone not familiar with it. There are many other ways to define:

- Define by category. Put the word or term in a larger organizational context. For example: patriotism can be put in term of military service or in another category like volunteering and giving back to one’s community.

- Define by example. For example, a good student is like Hermione Granger in the Harry Potter books; she is prepared, does not procrastinate, is not afraid to ask questions, but also is willing to help others without cheating.

- Define with a synonym. Use words that are similar. For example, a hipster is a bit like the beatniks of the 1950s, smart and stylish but also a source of ridicule by others.

- Define by operation. Break it down into parts/how it works. For example, a responsible parent has to be a mentor, role model, guidance counselor, therapist, and even a jailer on occasion.

- Define through historical process. Look at how word has evolved over time. For example, the word holocaust originally meant to be consumed by fire, but after World War II, the meaning changed. It now refers to the mass genocide of Jewish and other peoples by the Nazis.

- Define by negation. Define something by what it is not. You cannot do this extensively because eventually, you have to define it. For example, a Physician’s Assistant (PA) is not an MD (Medical Doctor). PAs can perform many of the same procedures as an MD and even prescribe medications but they can only assist in surgery and not perform it on their own. Also, PAs work under the supervision of an MD.

Persuasive writing: Narrative

Narrative is a special kind of persuasive writing. Examples of narrative include the personal narrative, the reflection paper, and the memoir. Often these are also called “essays.” Stories, long and short, are narratives. The idea in a narrative is for the audience to be moved a certain way, to have a sort of revelation, or to see something in a new light. This is why narrative writing is categorized under persuasive writing. You are trying to persuade an audience to behold a matter in a certain way—you are trying to stir their soul. One example of a narrative is a fairy tale that tells a moral.

Example of narrative: Fairy tale with moral – persuasive writing

The poor little sparrow was called Pride. Pride’s mother said, “Pride, leave the nest and make your way in the world.” So Pride tweeted farewell to her siblings and soared off towards the tallest tree.

At the top of the tallest pine tree in the forest, Pride made a nest. She could see for miles. She could see the weather vane on the roof of the barn in the valley over the hill. And every night she heard the wind in the pines just below her.

One day, as Pride was going about gathering worms on the ground far below, she heard a chipmunk squeaking at another chipmunk. “What are you quarreling over?” tweeted Pride. One chipmunk, whose name was Sam, said, “Joe here is not gathering quickly enough. And we have a party tonight. We have to be ready.” Pride nodded and said, “I believe I am invited to the party.” Sam looked and Joe, and Joe looked at Sam. “Why not?” they shrugged. “Seven o’clock.”

Pride fluttered back down to the plot of dirt happily. Just then she saw two worms wiggling in the dirt. She carefully picked them both up in her beak and began climbing through the air to her nest near the stars. But half-way up, she got so tired. And the worms were so heavy! So, regretfully, she dropped one of them. When she finally got to her nest, she was so tired, she put the worm on the table, sat in the armchair, and fell asleep.

When she woke, it was half past seven. She flew to the mirror, arranged her feathery hair, put on her best yellow bonnet, and began the trip to the chipmunks. She passed the tallest branches, then the middle branches, and then finally, she found the chipmunks by following the sound of the fiddle that filtered through the lowest branches.

“What are you doing here?” Sam asked her when he saw Pride entering the party room amid the broken balloons and empty cake pans. “Why, coming to the party,” she said. “It’s over,” he said. And he stretched out on a branch, fluffed his pillow, and snored off.

“Oh, no!” thought Pride. “Why, oh, why did I build my nest so high, and so far away from everybody else’s?”

The use of stories with interesting details are common in good narrative writing. For example, here is a line from Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men

This was Slim, the jerkline skinner. His hatchet face was ageless. He might have been thirty-five or fifty. His ear heard more than was said to him, and his slow speech had overtones not of thought, but of understanding beyond thought (33- 34).

You can see how exact and careful and clear this description is. Narrative writing often includes much figurative language. In other words, narrative writing focuses on the senses—how did it feel? How did it taste, and what did it smell like? There is also often a lot of dialogue in narrative writing. There is a clear beginning and a clear end. There is often a takeaway lesson, or memory. Sometimes, there is a plot with complexity and resolution. The topic is usually one of love, or envy, or death, or big choices, or something very interesting to humans.

In narrative writing, the thesis, or central claim, is often ambiguous or arguable— it cannot be pinpointed into one sentence, the way you can find a thesis sentence in an academic argument paper.

For example, what is the central argument of the superhero movies? It is not: "Monsters are pink." It is not "Everybody should go to college." It may be something like "Be strong" or "Believe in yourself" or "Work hard" or "Fight for what is right." And we perhaps can argue which of those is the main argument of each superhero movie. But we are all somewhere near each other in terms of what we think the argument, or claim, could be.

Persuasive writing: Rhetorical analysis

A rhetorical analysis seeks to convince an audience what is going on in a chosen text, in terms of the chosen text’s effect on its audience. The form of the thesis, or claim (or central argument) of a rhetorical analysis is the same in every rhetorical analysis. In other words, you don’t invent your own thesis statement when you write a rhetorical analysis; you simply fill in the blanks of the given form of the thesis of all rhetorical analyses, which is something like this:

In this rhetorical analysis, I am arguing that [Insert name of important text] is persuasive by means of _______.

Then, you give evidence to support your claim.

In rhetorical analyses, you very often give background about the text you are studying and telling your audience about. You also quote extensively from the text you are analyzing to provide the evidence to support your way of seeing how the text is persuasive. You also paraphrase your text and summarize it. As you can see, a rhetorical analysis is a very good exercise for getting really into the meat of what is going on in whatever text you choose to analyze.

For some examples:

- Maya Angelou’s poems are persuasive by means of her strong images and rhythms that feel so passionate.

- Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s speech “We have nothing to fear but fear itself” was persuasive because of ethos: the speaker had a great reputation as a leader.

- Martin Luther King Jr’s “I have a dream” speech was persuasive because of his displaying of the logic and common sense of our common humanity.

At the end of a rhetorical analysis, sometimes you, the writer, sum up why you think the text you studied is persuasive specifically to you—you being the audience.

The most common type of rhetorical analysis is the one that uses the Aristotelian categories of ethos, pathos, and logos to organize it. You put this formula into the first paragraph of your rhetorical analysis in some form and then just follow through on giving evidence to support your claim (thesis). Just as a reminder, ethos is the character or reputation of the writer of the text. Pathos is the emotional appeals or evoking of feelings that the text makes to occur in the audience, and logos is the logical elements in the text, the appeals to facts and reason and common sense (or, universal truths, in a sense).

Some tips for writing a good rhetorical analysis are:

- Choose a worthy text; do not choose a text that is irrelevant or that nobody cares about or will ever read.

- Read the text carefully and know it well; notate it and find good quotes in it.

- Summarize it.

- Feel if you have an emotional reaction. Document the emotion.

- Feel if you are moved by the logic and facts and common sense in the writing. Document it.

- Feel if you are respecting the author more and more as you read. Document that.

- Learn something about the writer of the text, if you can.

- Learn something about the historical situation of the text or the conversation that the text is involved with.

- Think about who else is interested in the text or the topic that the text discusses.

- Consider the audience of the text you are studying—how might they be moved or persuaded? What is the purpose?

- Make sure you entertain other points of view, or counter-arguments. This almost always strengthens your own argument because it displays that you know about and have carefully considered other stakeholders.

Example of rhetorical analysis – persuasive writing

I recently read “A Piece of Chalk” by G. K. Chesterton. The writer is persuasive by means of ethos, in that he creates a sense of trust in his reader by means of his facility with English and with his love for the things most humans love: Nature, philosophy, art. The writer is also persuasive by means of pathos, because he evokes an emotional response, even to things such as color, that is “red-hot” and “draws roses” and “black” which is “definite.” The writer is also persuasive by means of logos, or logic, but not data. For he gives all kinds of logical arguments, but to go along with them you have to agree with certain assumptions, which are almost always amazing and vast assumptions.

Chesterton persuades by ethos by presenting himself, the writer, as one who cares about humanity. For example, he says that others might draw a cow, but he draws “the soul of the cow,” so that it becomes something poetical and greater than it is in itself. He also describes himself in the first paragraph as a friendly person, as he interacts with the woman in the kitchen with humor. By mentioning things like “the pocketknife” and calling it “the infant of the sword,” Chesterton amuses with his fresh and touching uses of language.

Chesterton persuades by pathos because he is always mentioning emotion-laden topics and subjects, like “devils and seraphim” and “blind old gods” and “the live green figure of Robin Hood.” He does not call a path through a field a path through a field; he calls it “those colossal contours”, thus evoking a feeling of vastness and closeness and love for all of England. Everyone carries things in their pockets. But for Chesterton to call these items “primeval and poetical” is yet another example of his making a smiling feeling of the enormity of humanity’s cares out of something so small and inconsequential.

Chesterton persuades by logos not with providing an array of scientific facts, but by laying out statements that have amazing assumptions behind them. For example, he says that elements of the landscape being smooth “declares in the teeth of our timid and cruel theories that the mighty are merciful.” To assume that smoothness in nature is the same as smoothness of humankind is simply an amazing and amusing leap. In the end, he assumes that his audience is going to go along with his assumption that “white” is the color of “virtue.” This is easy to assume along with him, because he slips it into the narrative of his essay on virtue, which he says is “a vivid and separate thing.”

In my view, Chesterton is persuasive by means of ethos more than anything else. By presenting himself as a philosopher and one who cares deeply about man, the audience is easily persuaded to follow him wherever he leads them in his writing, and to agree with such a jolly, wise, and people-loving person, which is so refreshing in this, what Chesterton calls, this “pessimistic period” we live in.

Work cited

Chesterton, G. K. “A Piece of Chalk” [1905]. www.gkc.org.uk, http://www.gkc.org.uk/gkc/books/chalk.html. Accessed 14 Feb. 2018.

Persuasive writing: Literary analysis

To write a literary analysis, one picks an important text of literature. Then one makes a claim about it and supports that claim with evidence from the literature text itself, and sometimes also from sources that shed light on the literature text. The key to a good literary analysis is to deeply and closely read the literature text, come up with one clear claim that is reasonable, and support it by evidence, especially by quoting or paraphrasing or summarizing items from the text.

To use the example of D. H. Lawrence's short story “The Prussian Officer,” I could claim that the text is to be read as a commentary on the lostness of modern human life. I could support this by directly quoting from the end of the story, where we read:

He stared till his eyes went black, and the mountains, as they stood in their beauty, so clean and cool, seemed to have it, that which was lost in him (18).

I could find other portions of the text which also exhibit this sense of wandering and befuddlement. Notice that my interpretation can be argued against by others. Others may think the text is directed towards truths that are something somewhat different. But because my evidence is grounded in the literary text itself, my thesis, or claim, is most certainly at least a reasonable claim.

As with a rhetorical analysis, the thesis, or central claim, of every literary analysis essentially follows the same form. So somewhere you will see in every literary analysis this kind of claim: “The text, [Insert name of literary text], should be read as __________, because ____________.”

Tips for doing a literary analysis are:

- Grammar is important. Knowing what parts of speech are in the text and where and why, helps you make educated statements about them. For example, to know how to talk about a text as “written in the first person” versus “written in the third person” is necessary to writing a good literary analysis. For example, Moby Dick begins “Call me Ishmael.” This is the first person. It does not begin “There was a man named Ishmael,” which sends forth a very different feeling. Being able to notice this means knowing grammar.

- Things that are multicultural are nice to analyze, especially if you are trying to appeal to a wider audience.

- The more closely you read the literature text you are writing about, the better your analysis will be.

- Knowing the historical context and conversation of the text you are analyzing is also helpful.

- Showing that you know possible counter-claims to what you are claiming about the text will usually only strengthen your own case.

- Secondary sources--academic sources about the literature text you are examining--can sometimes be helpful.

Remember, when you write a literary analysis, you are writing to an audience of people who probably know and care about the text you are analyzing. So, already, you know that your audience is going to want you to care about and know about the text. For example, your audience could be the other members of your literature or composition course.

When reading the chosen literary text you are analyzing, look at themes, patterns, images, language, metaphors, interpretations, the plot line. As you read, think carefully about why the writer of the literary text chose one word and not another, why they put an image in where they put it, why they were silent in a certain place where you thought there would be something said—things like this.

Literary analyses are sometimes experience-based. In other words, you, the reader, simply write about how you responded to the text, how you reacted. This is experience-based persuasion, which is the next section. But even if you are writing an experience-based (often called a reader-response) literary analysis, you still must support your claims from the literary text and be prepared to defend them.

The following example is a simple version of a literary analysis because it does not involve citing anything other than the text under analysis. More advanced analyses often include references to the work of other scholars in the field who research the literary text.

Example of a literary analysis – persuasive writing

“Ode on a Grecian Urn,” and Depression

Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn” should be read as a confession of depression. The writer is clearly depressed. The maidens are “loth”—why can’t they be something more positive? There is a “mad pursuit” and a “struggle to escape.” To me that sounds kind of upsetting. And the entire poem is filled with references to that which the writer wants but cannot get, which makes the writer sound unfulfilled and sunken. For we read of “unheard” melodies and the bold lover in the poem is told he can “never, never” kiss the girl.

The author even admits that he, or someone, is left with “a heart high-sorrowful and cloy’d.” And we all know that cows often low because they are missing their mothers, or food, and here we have this poor “heifer lowing at the skies” in the poem. And who wouldn’t get depressed being reminded of “old age” and how this generation is being wasted by it?

Some might argue that at the end of the poem, the talk about truth being beauty and beauty being truth, is upbeat. But it sounds a little fraught to me, even there, for the unnamed narrator tells the audience “…—that is all / Ye know on earth.” If that’s it, and everything on earth is full of silent streets and we have just read about a place “desolate” and a person “for ever panting”, then, I ask you, where does this leave us? In a funk, that’s what I say.

Work Cited

Keats, John. “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” The Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44477/ode-on-a-grecian-urn. Accessed 14 Feb. 2018.

Persuasive writing: Experience-based persuasion

In college as well as in a job situation, most persuasive writing you do will have to do with persuading with logos, or facts and data. However, there is also experience-based writing that depends on style, passion (pathos), and experience (ethos). The following is an argument, or claim:

A man should never marry. I am charmed when I hear a man say, ‘I am still living alone.’ When I hear someone say, ‘He has married into so and so’s family’ or ‘He has taken such and such a wife and they are living together,’ I feel nothing but contempt for the man. He will be ridiculed by others too, who will say, ‘No doubt he thought that commonplace woman was quite a catch, and that’s why he took her off with him.’ Or, if the woman happens to be beautiful, they are sure to feel, ‘He dotes on her so much that he worships her as his private Buddha. Yes, that’s no doubt the case' (Kenko, Yoshida, “from Essays in Idleness” 2341)

The central thesis is the first line: “A man should not marry.” The writer then goes on to very feelingly support his view, his claim, his thesis. But he does not cite any data, or scientific research, to support his thesis. He is convincing by experience, by emotion, by character.

As the example above exhibits, any novel, poem, story, or similar writing can be also called an experience-based persuasion writing. Here, in this textbook, we focus on the more academic kind of experience-based persuasion text you are often asked to write in learning environments and job situations. The key in both kinds of persuasion writing, however, is that you must have a clear thesis or claim. You must stick to that same claim throughout your paper, and you must support it with evidence. You often do well to include the admission that there are valid possible counter-arguments to your claim, and you should refute them as best and reasonably as you can.

The difference between experience-based and research-based persuasion is only that experience-based persuasion is more subjective, non-scientific. It is more about how you, one person, feel about something.

Again, the form of an experience-based persuasion writing is:

- Claim (thesis) (as part of the introduction)

- Supporting reasons

- Consideration of counter-arguments (optional)

- Conclusion and resaying of claim (thesis).

You must have a clear, arguable thesis, and you must stick to that single claim throughout the entire text. You must give reasons to support your thesis. You do well to consider why your claim could be wrong—what good reasons there could be to oppose you. And then at the end you say your thesis again, in a fresh and memorable way. Feel free to look at models to get ideas.

Tip: To write experience-based persuasion, simply read news or postings on the internet on topics that you’re interested in. You will quickly find something to disagree with or argue against. Use that point of agreement or disagreement to start your paper.

Persuasive writing: Research-based persuasion

Research-based persuasion writing is similar to experience-based persuasion writing. The difference is that you, the writer, do not put so much of yourself into the argument. You come up with a working thesis, or claim, and then do research to find items to support your claim with facts and authorities.

Research-based persuasion writing is especially about trying to persuade an audience through their logic and reason.

It cannot be emphasized enough how careful you must be about phrasing and forming your thesis, or central claim, in research-based persuasion writing. If you say, “I argue that there are a lot of problems with crime in our country,” you cause your reader to become immediately lost. This is far too vague. If you claim, “Crime is bad,” then your reader shakes their head again—this is not an arguable argument, because who is going to plausibly argue against that claim? But if you say something like, “I argue that ______ has been proven to help improve the crime situation, based on data from ______, supported by researchers ________ and ______,” the reader knows that you know your data, you know your topic, you know your research, you know your issue, and you are acquainted with at least some of the other people involved in the issue.

Be very specific in your claim (thesis, argument)!

Secondly, you must be very careful about following through on your thesis. You must adhere to it throughout your writing, and you must finish the paper with essentially the same claim that you began it with.

As far as research for a research-based persuasion paper, the key here is to find important, relevant research. To do this, you must skim many texts and find what you need.

Also key here is to document your sources. Keep track of what you are reading, and document where you got everything. And finally, quote from your sources accurately and fairly. And if something is a quote, keep it in quotes.

Do not just lift someone else’s words and pass them off as your own!

Ethos, or having a tone of ethical responsibility, is important in a research-based persuasion writing as well. You do well to follow the general ways and forms of the people who are in the field you are writing in. You do well to present yourself as you actually are, with honesty. You can be as passionate about your topic as you like, but be fair and reasonable. Look at counter-arguments lucidly and considerately. Keep your tone professional, clear, and genuine, as much as possible.

Professional writing

In a professional email, you want to greet the recipient or recipients politely. You want to use proper grammar and have a calm and consistent style. Stay with the business matter at hand. You want to break up your writing into clear and separate topics—think organization and structure, so that any decision-makers above you or equal to you can quickly find what information they need, using short and to-the-point sentences.

Remember always that your email is a public document, no matter how private it may seem to you. And don’t phrase anything in an email differently than what you would say to the recipient face to face.

Example of professional writing: emails

4 February 2015

Dear Colleagues

cc: Jim Boss

Our method of reserving the main conference room in Room 412 used to be a sign-up sheet at my desk here in Room 12. We are moving to an online sign-up sheet for the use of the main conference room, beginning tomorrow at 8am.

To reserve the room now, one simply goes to the website, www.conferenceroom412.com, and clicks on the block of time (in ½ hour increments) that one wishes to reserve the room for. The system will automatically fill in your contact information and block out the time for you. You can fill in as much information as you would like about your use of the room.

In the event that there is a scheduling conflict, and two people wish to reserve the room at the same time, the procedure for resolving the conflict is the same as before: email me and I will resolve the conflict within two hours of receipt of your email.

If you have any questions about this new method, please contact me.

Regards,

Jane Secretary

Administrative Assistant

Business XYZ Jane.secretary@businessxyz.com

763-222-1763

Room 12

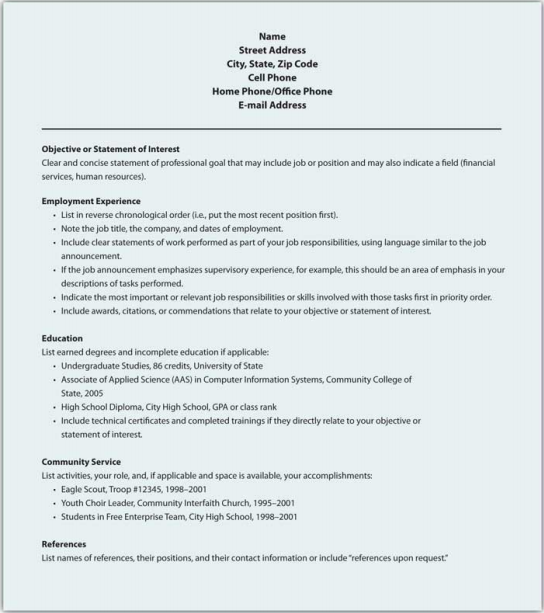

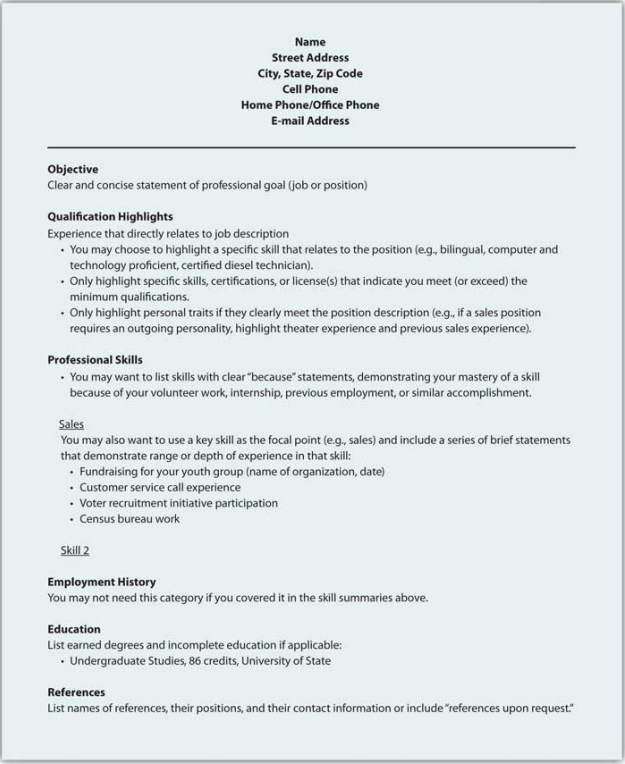

Professional writing: Résumés and cover letters

Résumés are important for working people. A résumé tells the reader who you are, what you have done, and why they should hire you. It does not use sentences so much as it uses bullet-points, white space, and brief data phrases. The goal is to accurately and quickly display oneself to a potential employer. In writing a résumé, do not have errors. Carefully proof-read what you have in your résumé before you send it. Simply list your name, your education, your qualifications, and your work history, but avoid all personal pronouns. Utilize active verbs to describe your experience.

The key to good résumé writing is accuracy, conciseness, and consistency.

Example of cover letter:

14 July 2017

Human Resources Director

Weatherford Public Schools

Weatherford, MN

Dear Human Resources Director,

As my résumé indicates, I have extensive experience managing the grounds and facilities of schools. I would appreciate it if you would carefully consider my application to be head janitor at the Weatherford Public Schools. I am honest, good with people, and very responsible. I believe this is why I was promoted from janitor to head janitor at Midland Public Schools, which job I presently hold.

When there is a problem in the school, I fix it immediately, or find out how to get the resources together to get it fixed as soon as possible. I document everything, and the safety of the students and staff is my highest priority. Along with this, I also keep a productive and happy team going every day.

I can provide references to you, of people familiar with me and my work, who will also inform you as to my excellent worth and qualifications for the position of head janitor.

My contact information is below and on my résumé. I very much look forward to hearing back from you soon, to discuss the possibility of me coming to work at Weatherford Public Schools to serve you, your students, your staff, and your community.

Regards,

Joe Schmo

763-763-7676

1234 Tree Street

Midland, MN 55555

Examples of résumés:

Chronological résumé from Business English for Success from Saylor Books.

Functional Résumé from Business English for Success from Saylor Books.

Professional writing: Social media postings

Why do we include a little note about social media postings under professional writing? Because your social media postings are part of your public ethos, or reputation, and they will remain with you. What conclusions will your peers draw from your postings on Twitter? What will a future potential employer think in reviewing your Facebook profile?

Appropriate social media posting:

Finished my last final exam today! Ready for the next steps, whatever they be!

Not appropriate:

Done with exams! Hello Jack Daniels. See you in a week!

Keep in mind that you can always create private Facebook or other social media groups for your friends and family—or have two separate accounts, one for professional use and another for more casual communications.

Always be aware that potential employers may still be able to see any public accounts.

That’s it. Now you can move on to drafting a paper. You know your mode, you have an idea of its form. Start typing!