2.2: Prewriting

- Page ID

- 20292

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Prewriting is an essential activity for most writers. Through robust prewriting, writers generate ideas, explore directions, and find their way into their writing. When students attempt to write an essay without developing their ideas, strategizing their desired structure, and focusing on precision with words and phrases, they can end up with a “premature draft”—one that is more writer-based than reader-based and, thus, might not be received by readers in the way the writer intended.

In addition, a lack of prewriting can cause students to experience writer’s block. Writer’s block is the feeling of being stuck when faced with a writing task. It is often caused by fear, anxiety, or a tendency toward perfectionism, but it can be overcome through prewriting activities that allow writers to relax, catch their breath, gather ideas, and gain momentum.

The following exist as the goals of prewriting:

- Contemplating the many possible ideas worth writing about.

- Developing ideas through brainstorming, freewriting, and focused writing.

- Planning the structure of the essay overall so as to have a solid introduction, meaningful body paragraphs, and a purposeful conclusion.

Discovering and Developing Ideas

Quick Prewriting Activities

Quick strategies for developing ideas include brainstorming, freewriting, and focused writing. These activities are done quickly, with a sense of freedom, while writers silence their inner critic. In her book Wild Mind, teacher and writer Natalie Goldberg describes this freedom as the “creator hand” freely allowing thoughts to flow onto the page while the “editor hand” remains silent. Sometimes, these techniques are done in a timed situation (usually two to ten minutes), which allows writers to get through the shallow thoughts and dive deeper to access the depths of the mind.

Brainstorming begins with writing down or typing a few words and then filling the page with words and ideas that are related or that seem important without allowing the inner critic to tell the writer if these ideas are acceptable or not. Writers do this quickly and without too much contemplation. Students will know when they are succeeding because the lists are made without stopping.

Freewriting is the “most effective way” to improve one’s writing, according to Peter Elbow, the educator and writer who first coined the term “freewriting” in pivotal book Writing Without Teachers, published in 1973. Freewriting is a great technique for loosening up the writing muscle. To freewrite, writers must silence the inner critic and the “editor hand” and allow the “creator hand” a specified amount of time (usually from 10 to 20 minutes) to write nonstop about whatever comes to mind. The goal is to keep the hand moving, the mind contemplating, and the individual writing. If writers feel stuck, they just keep writing “I don’t know what to write” until new ideas form and develop in the mind and flow onto the page.

Focused freewriting entails writing freely—and without stopping, during a limited time—about a specific topic. Once writers are relaxed and exploring freely, they may be surprised about the ideas that emerge.

Researching

Unlike quick prewriting activities, researching is best done slowly and methodically and, depending on the project, can take a considerable amount of time. Researching is exciting, as students activate their curiosity and learn about the topic, developing ideas about the direction of their writing. The goal of researching is to gain background understanding on a topic and to check one’s original ideas against those of experts. However, it is important for the writer to be aware that the process of conducting research can become a trap for procrastinators. Students often feel like researching a topic is the same as doing the assignment, but it’s not.

The two aspects of researching that are often misunderstood are as follows:

- Writers start the research process too late so the information they find never really becomes their own setting themselves up for way more quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing the words of others than is appropriate for the 70% one’s own words and 30% the words of others ratio necessary for college-level research-based writing.

- Writers become so involved in the research process that they don’t start the actual writing process soon enough so as to meet a due date with a well written, edited, and revised finished composition.

Being thoughtful about limiting one’s research time—and using a planner of some sort to organize one’s schedule—is a way to keep oneself from starting the research process too late to

See Part V of this book for more information about researching.

Audience and Purpose

It’s important that writers identify the audience and the purpose of a piece of writing. To whom is the writer communicating? Why is the writer writing? Students often say they are writing for whomever is grading their work at the end. However, most students will be sharing their writing with peers and reviewers (e.g., writing tutors, peer mentors). The audience of any piece of college writing is, at the very minimum, the class as a whole. As such, it’s important for the writer to consider the expertise of the readers, which includes their peers and professors). There are even broader applications. For example, students could even send their college writing to a newspaper or a legislator, or share it online for the purpose of informing or persuading decision-makers to make changes to improve the community. Good writers know their audience and maintain a purpose to mindfully help and intentionally shape their essays for meaning and impact. Students should think beyond their classroom and about how their writing could have an impact on their campus community, their neighborhood, and the wider world.

Planning the Structure of an Essay

Planning Based on Audience and Purpose

Identifying the target audience and purpose of an essay is a critical part of planning the structure and techniques that are best to use. It’s important to consider the following:

- Is the the purpose of the essay to educate, announce, entertain, or persuade?

- Who might be interested in the topic of the essay?

- Who would be impacted by the essay or the information within it?

- What does the reader know about this topic?

- What does the reader need to know in order to understand the essay’s points?

- What kind of hook is necessary to engage the readers and their interest?

- What level of language is required? Words that are too subject-specific may make the writing difficult to grasp for readers unfamiliar with the topic.

- What is an appropriate tone for the topic? A humorous tone that is suitable for an autobiographical, narrative essay may not work for a more serious, persuasive essay.

Hint: Answers to these questions help the writer to make clear decisions about diction (i.e., the choice of words and phrases), form and organization, and the content of the essay.

Use Audience and Purpose to Plan Language

In many classrooms, students may encounter the concept of language in terms of correct versus incorrect. However, this text approaches language from the perspective of appropriateness. Writers should consider that there are different types of communities, each of which may have different perspectives about what is “appropriate language” and each of which may follow different rules, as John Swales discussed in “The Concept of Discourse Community.” Essentially, Swales defines discourse communities as “groups that have goals or purposes, and use communication to achieve these goals.”

Writers (and readers) may be more familiar with a home community that uses a different language than the language valued by the academic community. For example, many people in Hawai‘i speak Hawai‘i Creole English (HCE colloquially regarded as “Pidgin”), which is different from academic English. This does not mean that one language is better than another or that one community is homogeneous in terms of language use; most people “code-switch” from one “code” (i.e., language or way of speaking) to another. It helps writers to be aware and to use an intersectional lens to understand that while a community may value certain language practices, there are several types of language practices within our community.

What language practices does the academic discourse community value? The goal of first-year-writing courses is to prepare students to write according to the conventions of academia and Standard American English (SAE). Understanding and adhering to the rules of a different discourse community does not mean that students need to replace or drop their own discourse. They may add to their language repertoire as education continues to transform their experiences with language, both spoken and written. In addition to the linguistic abilities they already possess, they should enhance their academic writing skills for personal growth in order to meet the demands of the working world and to enrich the various communities they belong to.

Use Techniques to Plan Structure

Before writing a first draft, writers find it helpful to begin organizing their ideas into chunks so that they (and readers) can efficiently follow the points as organized in an essay.

First, it’s important to decide whether to organize an essay (or even just a paragraph) according to one of the following:

- Chronological order (organized by time)

- Spatial order (organized by physical space from one end to the other)

- Prioritized order (organized by order of importance)

There are many ways to plan an essay’s overall structure, including mapping and outlining.

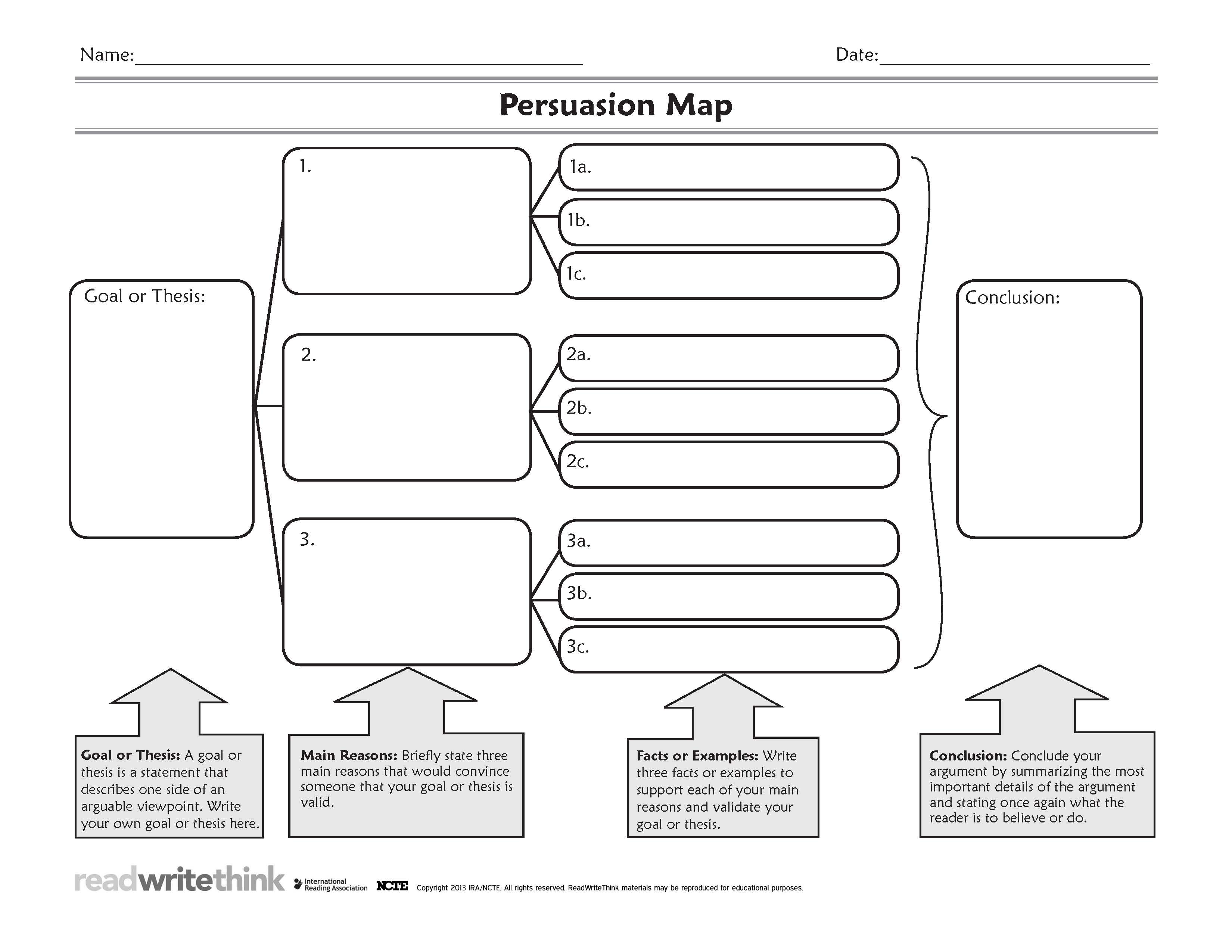

Mapping (which sometimes includes using a graphic organizer) involves organizing the relationships between the topic and other ideas. The following is example (from ReadWriteThink.org, 2013) of a graphic organizer that could be used to write a basic, persuasive essay:

Persuasion Map. Copyright 2013 IRA/NCTE. All rights reserved. ReadWriteThink materials may be reproduced for educational purposes.

Outlining is also an excellent way to plan how to organize an essay. Formal outlines use levels of notes, with Roman numerals for the top level, followed by capital letters, Arabic numerals, and lowercase letters. Here’s an example:

- Introduction

- Hook/Lead/Opener: According to the Leilani was shocked when a letter from Chicago said her “Aloha Poke” restaurant was infringing on a non-Hawaiian Midwest restaurant that had trademarked the words “aloha” (the Hawaiian word for love, compassion, mercy, and other things besides serving as a greeting) and “poke” (a Hawaiian dish of raw fish and seasonings).

- Background information about trademarks, the idea of language as property, the idea of cultural identity, and the question about who owns language and whether it can be owned.

- Thesis Statement (with the main point and previewing key or supporting points that become the topic sentences of the body paragraphs): While some business people use language and trademarks to turn a profit, the nation should consider that language cannot be owned by any one group or individual and that former (or current) imperialist and colonialist nations must consider the impact of their actions on culture and people groups, and legislators should bar the trademarking of non-English words for the good of internal peace of the country.

- Body Paragraphs

- Main Point (Topic Sentence): Some business practices involve co-opting languages for the purpose of profit.

- Supporting Detail 1: Information from Book 1—Supporting Sentences

- Subpoint

- Supporting Detail 2: Information from Article 1—Supporting Sentences

- Subpoint

- Subpoint

- Supporting Detail 1: Information from Book 1—Supporting Sentences

- Main Point (Topic Sentence): Language cannot be owned by any one group or individual.

- Supporting Detail 1: Information from Book 1—Supporting Sentences

- Subpoint

- Supporting Detail 2: Information from Article 1—Supporting Sentences

- Subpoint

- Subpoint

- Supporting Detail 1: Information from Book 1—Supporting Sentences

- Main Point (Topic Sentence): Once (or currently) imperialist and colonialist nations must consider the impact of their actions on culture and people groups.

- Supporting Detail

- Subpoint

- Supporting Detail

- Legislators should bar the trademarking of non-English words for the good and internal peace of the country.

- Main Point (Topic Sentence): Some business practices involve co-opting languages for the purpose of profit.

- Conclusion (Revisit the Hook/Lead/Opener, Restate the Thesis, End with a Twist—a strong more globalized statement about why this topic was important to write about)

Note about outlines: Informal outlines can be created using lists with or without bullets. What is important is that main and subpoint ideas are linked and identified.

- Use 10 minutes to freewrite with the goal to “empty your cup”—writing about whatever is on your mind or blocking your attention on your classes, job, or family. This can be a great way to help you become centered, calm, or focused, especially when dealing with emotional challenges in your life.

- For each writing assignment in class, spend three 10-minute sessions either listing (brainstorming) or focused-writing about the topic before starting to organize and outline key ideas.

- Before each draft or revision of assignments, spend 10 minutes focused-writing an introduction and a thesis statement that lists all the key points that supports the thesis statement.

- Have a discussion in your class about the various language communities that you and your classmates experience in your town or on your island.

- Create a graphic organizer that will help you write various types of essays.

- Create a metacognitive, self-reflective journal: Freewrite continuously (e.g., 5 times a week, for at least 10 minutes, at least half a page) about what you learned in class or during study time. Document how your used your study hours this week, how it felt to write in class and out of class, what you learned about writing and about yourself as a writer, how you saw yourself learning and evolving as a writer, what you learned about specific topics. What goals do you have for the next week?

During the second half of the semester, as you begin to tackle deeper and lengthier assignments, the journal should grow to at least one page per day, at least 20 minutes per day, as you use journal writing to reflect on writing strategies (e.g., structure, organization, rhetorical modes, research, incorporating different sources without plagiarizing, giving and receiving feedback, planning and securing time in your schedule for each task involved in a writing assignment) and your ideas about topics, answering research questions, and reflecting on what you found during research and during discussions with peers, mentors, tutors, and instructors. The journal then becomes a record of your journey as a writer, as well as a source of freewriting on content that you can shape into paragraphs for your various assignments.

Works Cited

Elbow, Peter. Writing Without Teachers. 2nd edition, 1973, Oxford UP, 1998.

Goldberg, Natalie. Wild Mind : Living the Writer’s Life. Bantam Books, 1990.

Swales, John. “The Concept of Discourse Community.” Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings, 1990, pp. 21-32.

For more about discourse communities, see the online class by Robert Mohrenne “What is a Discourse Community?” ENC 1102 13 Fall 0027. University of Central Florida, 2013.