3.2: Brainstorming Techniques

- Page ID

- 69731

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Article links:

“Idea Mapping” provided by University of Minnesota

“Journalistic Questions” provided by Writing Commons

“Clustering: Spider Maps” provided by Writing Commons

Chapter Preview

- List the benefits of brainstorming.

- Describe the idea mapping method of brainstorming.

Idea Mapping

provided by University of Minnesota

Idea mapping allows you to visualize your ideas on paper using circles, lines, and arrows. This technique is also known as clustering because ideas are broken down and clustered, or grouped together. Many writers like this method because the shapes show how the ideas relate or connect, and writers can find a focused topic from the connections mapped. Using idea mapping, you might discover interesting connections between topics that you had not thought of before.

To create an idea map, start with your general topic in a circle in the center of a blank sheet of paper. Then write specific ideas around it and use lines or arrows to connect them together. Add and cluster as many ideas as you can think of.

Notice Mariah’s largest circle contains her general topic, mass media. Then, the general topic branches into two subtopics written in two smaller circles: television and radio. The subtopic television branches into even more specific topics: cable and DVDs. From there, Mariah drew more circles and wrote more specific ideas: high definition and digital recording from cable and Blu-ray from DVDs. The radio topic led Mariah to draw connections between music, downloads versus CDs, and, finally, piracy.

From this idea map, Mariah saw she could consider narrowing the focus of her mass media topic to the more specific topic of music piracy.

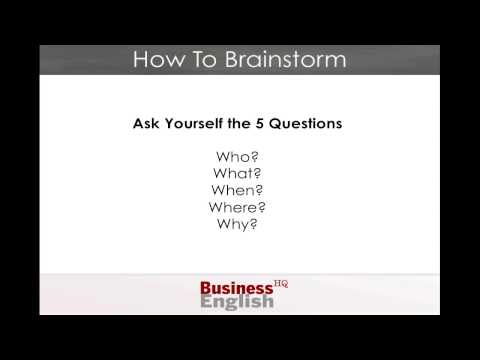

Journalistic Questions

provided by Writing Commons

Question | ||

| 1. Who? | Who is doing this? | Who will do this? |

| 2. What? | What did they do? | What was it for? |

| 3. Where? | Where did they do it? | Where is it going to happen? |

| 4. Why? | Why are they doing this? | Why are they doing it? |

| 5. When? | When is it happening? | When is it going to happen? |

| 6. How? | How did they do it? | How do they hope to do it? |

Clustering: Spider Maps

provided by Writing Commons

Use visual brainstorming to develop and organize your ideas.

Cluster diagrams, spider maps, mind maps–these terms are used interchangeably to describe the practice of visually brainstorming about a topic. Modern readers love cluster diagrams and spider maps because they enable readers to discern your purpose and organization in a moment.

When Is Clustering/Spider Mapping Useful?

As depicted below, writers use clustering to help sketch out ideas and suggest logical connections. In this way, writers use cluster diagrams and spider maps as an invention tool. When clustering, they do not impose an order on their thinking. Instead, after placing the idea in the center of the page, they then free-associate.

Remembering that the goal is to generate ideas, make the drawing visually attractive, perhaps using color or a variety of geometric shapes and layout formats. Typical cluster and spider maps resemble the following:- Branches: If ideas seem closely related to you, consider using small branches, like tree limbs, to represent their similarities.

- Arrows: Use arrows to represent processes or cause and effect relationships.

- Groupings: If a number of ideas are connected, go ahead and put a circle around them.

- Bullets: List ideas that seem related.

Online Cluster/Spider Maps

- Visual thesaurus: This online software application draws cluster diagrams around words. Plug in a word and watch similar terms spin around it. Give it time and you’ll see many interesting associations.

- Forest management: View an example of a hand-drawn cluster map.

- Sociograms: Two well-functioning teams: Social network analysis encourages visual depictions of people’s collaborative networks.

- Social networks: Examples of how maps of social networks can be drawn. Evaluating the alcohol environment: Here cluster maps are drawn to show correlations between bars and violent crime.

- Crime patterns made clear for Portland, Oregon, citizens via Internet mapping: This essay provides examples of how crime maps show patterns in criminal be

When Are Clustering/Spider Maps Useful?

- Clustering is a particularly effective strategy during the early part of a writing project when you’re working to define the scope and parameters of a project.

- Congue Clustering can help you identify what you do know and what you need to research about a topic.

Important Concepts

idea mapping

visually brainstorming

Licenses and Attributions

CC LICENSED CONTENT, ORIGINAL

Composing Ourselves and Our World, Provided by: the authors. License: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

This chapter contains an adaptation from 8.1 Apply Prewriting Models by University of Minnesota and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This chapter contains an adaptation of Ten Ways To Think About Writing: Metaphoric Musings for College Writing Students by E. Shelley Reid This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 license.

- Video 1: Brainstorming Techniques License: Standard YouTube License Attribution: Business English.