4.5: Writing Process- Making the Personal Public

- Page ID

- 134542

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Develop a writing project through multiple drafts.

- Apply correct genre conventions for structure, paragraphs, tone, and mechanics.

- Write with purposeful shifts in voice, diction, tone, formality, and structure appropriate to personal narratives.

- Proficiently employ cultural and language variations in composition.

- Experience the collaborative and social aspects of writing processes.

- Give and act on productive feedback to works in progress.

Now it’s your turn to put pen to paper and experience the genre through action. Once you choose a moment to write about and begin the narrative process, you may want to rearrange, rewrite, or even omit some parts entirely. The goal is to create a story that not only gets your message across but also creates an emotional connection with your readers.

Summary of Assingment: A Turning Point

Choose an event from your life that has stuck in your memory as a turning point of some sort. Certainly, you can write about major milestones—graduations, achievements, and the like—but consider small moments and events, too: something that someone said to you or that you overheard, a time you got or didn’t get what you wanted, a time you were disappointed, or a time you thought you knew better than a more experienced person. To get the most accurate perspective of the event, go back in time as far as you can so that you think about the event as objectively as possible and know it as a real and meaningful turning point. Write a story about the event, and use narrative techniques to show why the event has become meaningful. Here are some other ideas about possible turning points:

- A changed attitude toward a friend, sibling, or other family member

- A change of major, if that change is a big step away from what you planned to do

- Making or not making the cut for a team or some other group

- Your feelings when you learned something about yourself or someone close to you

- A move from another country to the United States or from another U.S. location to where you are now

- Becoming fluent in another language

- Realizing that a certain behavior either gets you what you want or doesn’t

- Realizing that someone you admire is not so admirable, or vice versa

- Becoming friends with someone you didn’t expect to be friends with

- Facing an illness or crisis and how it changed or didn’t change you

Another Lens. An alternative to writing a first-person narrative about a turning point is to consider writing about the event from the perspective of someone—or something—else. If the story involves another person in addition to yourself, consider making that person the narrator and having them tell the story as they might view it.

Also consider telling your story from an outside observer’s perspective, or even from the perspective of an inanimate object—for example, the pen used to sign a contract. This perspective may be beneficial for exploring your own emotions and may also offer a helpful alternative if including details about your personal life in your story makes you uncomfortable.

Quick Launch: Plot Diagram

Once you have chosen a topic, freewrite for 5 to 10 minutes, considering the following questions:

- Why is this event memorable?

- What conflict did you face?

- What images come to mind when you think of this event?

Then, begin to isolate details to create a plot diagram. Remember, following a plot diagram involves focusing on the building of tension surrounding the conflict in a story and then resolving it in a meaningful way.

Drafting: Conflict, Point of View, Organization, and Reflection

With the skeleton of a plot diagram in mind, freewrite again for 5 to 10 minutes, considering the following questions:

- Why is this event memorable?

- What conflict did you face?

- What images come to mind when you think of this event?

- What do you want to express to your readers about the event?

- What lessons did you learn from the event?

Purpose

Along with your freewrite, consider what message you want to leave with readers. The reason this moment is important to you should be made clear to readers through the development of the story, most often through the conflict and its resolution. Remember that the conflict is the primary problem or obstacle that the main character—most likely you in this personal narrative—faces and must overcome in order to reach a resolution. Conflict in a personal narrative, as in fiction, usually consists of one or more of five main conflict types:

- Character vs. character

- Character vs. self

- Character vs. environment or nature

- Character vs. society

- Character vs. fate or the supernatural

The purpose and theme are shaped by the conflict. Consider the conflict in the Mark Twain excerpt. Twain needs to run a crossing that, at the beginning of the passage, he feels confident to handle. But as the story progresses and Mr. Bixby sends more people to make him nervous, Twain begins to second-guess himself.

But that did the business for me. My imagination began to construct dangers out of nothing, and they multiplied faster than I could keep the run of them. All at once I imagined I saw shoal water ahead! The wave of coward agony that surged through me then came near dislocating every joint in me. All my confidence in that crossing vanished. I seized the bell-rope; dropped it, ashamed; seized it again; dropped it once more; clutched it tremblingly once again, and pulled it so feebly that I could hardly hear the stroke myself.

This conflict not only builds the reader’s interest in the main character’s problem but also helps Twain develop the theme, his message to the reader: you must rely on your knowledge and training rather than second-guess yourself. In this anecdote, the theme is explicitly stated, but more often than not, authors are more subtle, requiring readers to infer themes on the basis of details in the text. The ways in which you craft your conflict and theme will affect its significance to your readers.

To help you organize you work, complete a graphic organizer like Table \(4.1\) as you are able at this point. You may want to revise it later as you write your draft.

| Basic Story Elements | |

| Purpose | |

| Conflict | |

| Main Characters | |

| Theme | |

Plot Elements

Now that you have considered your overall message and have a general idea of what you will write about, think of how you will structure your story. You already have diagrammed some of the Mark Twain excerpt and know how plots move along. One idea for organizing the plot of your narrative is to write down individual moments or events on notecards and physically place them on a table to mimic a hands-on plot diagram. You should have a series of events leading to the climax and fewer events that make up the falling action. This method of plot diagramming also helps you identify where holes may turn up in your plan. For example: Is your exposition missing key background information that is necessary for readers to understand the story? Have you created sufficient tension in the lead-up to the climax of your story? Examine your plot diagram to identify where you need more (or perhaps less) detail in your outline. You might notice that the plot diagram is a bit lopsided, skewing left. If it does, then much of your story leads up to the climax, as it should, with fewer words between the climax and resolution.

Most, but not all, personal narratives are written in chronological order; that is, the storyteller follows the sequence of events according to the order in which they occur. However, there are other structures, such as anecdotes told according to theme, through flashbacks, or in reverse chronological order. The order in which you recount events is important in building tension in the story, thus stimulating readers’ curiosity. Seriously consider how each choice that you make will create readers’ engagement and emotional connection to your story as you plan toward the climax.

Exposition

Next, follow your plot diagram to begin writing your narrative. Start with a strong introduction. Try to think of this introductory section as the “hook,” engaging readers so that they want to continue reading. Create the introduction with vivid details or a relatable anecdote. Remember that this section will introduce the main characters, the setting, and the conflict. Here are some suggestions for an opening strategy, all of which should be brief, generally not more than two paragraphs:

- Anecdote related to your story

- Description of one of the characters involved

- Scenario in which you ask readers what they might do in that situation

- Description of a setting in which you found yourself

- Significant dialogue or action that you will explain later

- One or more open-ended questions that relate closely to the theme; avoid yes/no questions

Transitions

As you do in other writing, build your overall structure through transitions—words and phrases you use to move readers through events, ideas, and time. Transitions smooth connections between ideas, clarifying them and making reading easier. In narratives, transitions often indicate the passage of time. They may also introduce new characters or ideas, tie ideas together, or make connections to the larger theme or message.

Transitions may be concrete, as is the one Mark Twain uses: “Well, one matchless summer’s day. . .” This statement clearly establishes the passage of time. But transitions can also be abstract or subtle, helping the author organize ideas and information. More subtle transitions include changes in elements such as tone, voice, point of view, or even setting. Use the plot diagram as an outline, and move from event to event as you draft your narrative. You will have freedom with paragraph length and structure because you will use dialogue and description. Also, some events or characters may require more detail than others. As you write your narrative, use transitions to move readers along until you ultimately resolve the central conflict and tie its resolution to the theme.\

Point of View

Authors have options for narrating a literary work—that is, they can choose from whose point of view they tell the story. In your narrative, you most likely will use the first-person point of view. When a story is told from this point of view, the narrator is a character in the story and tells it as it happens—that is, as the narrator experiences the event. Mark Twain tells his story from the first-person point of view in the excerpt from Life on the Mississippi. The first sentence of that excerpt reads, “Mr. Bixby served me in this fashion once, and for years afterward I used to blush even in my sleep when I thought of it.” Not only do readers understand that the narrator is telling the story, using pronouns such as me and I, but the narrator also describes his feelings (“blush[ing] even in my sleep”) and thoughts. For more information about point of view, see Editing Focus: Characterization and Point of View and Point of View.

Charcters

Characters in a personal narrative are generally real people, at least in part. As the author, you can focus on certain character traits and ignore, minimize, or exaggerate others. In making the people in your narrative come to life, you will likely assign them different ways of behaving and speaking. For example, one character may use long words and speak condescendingly to another. Another character may find conversation difficult and say little, relying on gestures more than words. Still another character might be generous, sympathetic, arrogant, or sneaky. When creating characters, make sure the characters’ language and behavior reflect their characterizations. For more information about characterization, see Editing Focus: Characterization and Point of View.

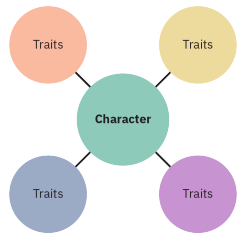

You can use a web diagram, similar to the one shown in Figure \(4.7\), to keep track of characters’ traits.

Figure \(4.7\) Character web (attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license

Setting

Where and when your narrative takes place is an important part of a narrative, as it is in the excerpt from Twain’s story. You may want to describe a setting in detail if it is important in the course of the story, or you may find it a less essential part of the narrative. In either case, the setting must be described to some extent to give the narrative a sense of time and place.

Verb Tense

Choose the tense in which you want to tell your story, and ensure that you stay consistent throughout the narrative. Typically, you will choose between past tense and present tense. Past tense provides a familiar sense of storytelling, as Twain develops in his anecdote: “I looked around, and there stood Mr. Bixby, smiling a bland, sweet smile.” Another option is to tell your story in the present tense, which provides a sense of urgency to the events and allows readers to feel closer to the action. If you are considering using the present tense, try substituting it in the excerpt from Life on the Mississippi. Consider how it sounds and the difficulties you might encounter in using it. Whichever tense you choose, however, the most important thing is to stick to it, changing it only to indicate a change in chronology. For example, if you are narrating in the present tense and want to indicate something that happened at a time before the events of your story, you would change tenses for clarity. Read more about verb tense consistency in Editing Focus: Verb Tense Consistency.

Active vs. Passive Voice

Verbs have two voices: active and passive. In an active-voice sentence structure, the subject performs the action of the verb. In a passive-voice sentence structure, the subject receives the action of the verb. Consider the examples in Table \(4.2\).

| Active Voice | Passive Voice |

| I devoured the silky pudding. | The silky pudding was devoured by me. |

| The teacher will give you directions. | Directions will be given to you by the teacher. |

| The barnacles scraped my skin. | My skin was scraped by the barnacles. |

| The sloth carried her baby on her back. | The baby sloth was carried by its mother on her back. |

| The two presidents are signing the agreement. | The agreement is being signed by the two presidents. |

| A tornado destroyed the neighborhood. | The neighborhood was destroyed by a tornado. |

The meanings in both passive and active voice remain the same, yet their effect is different. In active voice, the message will be clearer and often more convincing. While it is not wrong to write in the passive voice on occasion, you will usually strengthen your writing by focusing on how a subject performs an action rather removing it from the direct action. For more information about active and passive voice, see Clear and Effective Sentences.

Imagery

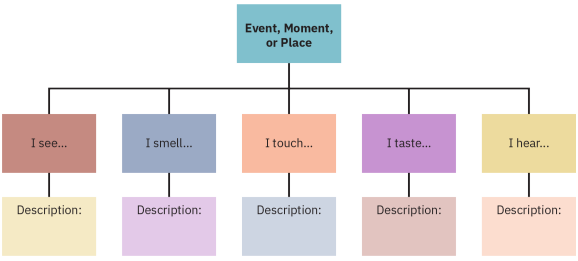

In personal narratives and memoirs, imagery not only brings the experience to life but also engages readers through their senses. For example, Twain appeals to the sense of hearing when he describes “the leadsman’s sepulchral cry:—‘D-e-e-p four!’” The use of figurative language, such as similes, metaphors, hyperbole, or personification, often enhances these descriptions. Think of images and figurative language as ways of showing versus telling. Consider Twain’s recounting of the moment he loses his nerve: “I began to climb the wheel like a squirrel.” Certainly, he could have said instead, “I spun the wheel back and forth.” But the use of figurative language, in this case a simile comparing his action to a squirrel’s, helps readers imagine and share Twain’s terror as if they are experiencing the event in the same way. Within a scene in your story, choose an event, moment, or place, and practice using imagery to describe it. Then use a graphic organizer like Figure \(4.8\) to imagine how you might use each sense to describe the same event or another event, moment, or place from your story.

Figure \(4.8\). Senses chart (CC BY 4.0; Rice University & OpenStax)

For your narrative, you do not have to use all the descriptions in the graphic organizer, and doing so would likely clutter your story. Choose the best, most powerful details to enhance your writing and help readers viscerally experience the event, moment, or place.

Sentence Structure

You can structure your text in various ways to achieve your intended mood, tone, and overall message. No matter what your form or style, sentences are your main units of composition, explaining the world in terms of subjects, actions, and objects: some force (a subject) does something (action) that causes something else to happen (an object). Narrative writing, like all prose, is built around complete and predictable sentences.

Sometimes, however, writers use sentences in less predictable and more playful ways. For example, fragmented sentences suggest fragmented stories. Fragmented sentences can be used judiciously in conventional writing, even academic writing, as long as their purpose is clear and your fragment is not mistaken for a grammatical error. Writers sometimes use fragments audaciously and sometimes with abandon to create the special effects they want: A flash of movement. A bit of a story. A frozen scene.

Fragments force quick reading, ask for impressionistic understanding, and suggest parts rather than wholes. Like snapshots, fragments invite strong reader participation to stitch information together and move toward clear meaning. Fragmented sentences suggest, too, that things are moving fast. Often used in dialogue as well to mimic real speech, purposeful fragments can be powerful: Deliberate. Intentional. Careful. Functional. Usually brief.

Consider British novelist Charles Dickens’s (1812–1870) use of fragments in this story told in The Pickwick Papers (1836). The impact of the sentence fragments here conveys a sensory experience and creates a mood for the reader.

“Heads, heads—take care of your heads!” cried the loquacious stranger, as they came out under the low archway, which in those days formed the entrance to the coach-yard. “Terrible place—dangerous work—other day—five children—mother—tall lady, eating sandwiches—forgot the arch—crash—knock—children look round—mother’s head off—sandwich in her hand—no mouth to put it in—head of a family off—shocking, shocking!”

On the opposite pole of sentence structure are labyrinthine sentences. A labyrinthine sentence seems never to end. Instead, it goes on and on and on, using all sorts of punctuational and grammatical tricks to create a compound sentence (two or more independent clauses joined by a comma and a conjunction such as and, or, or but) or a complex sentence (one independent clause with one or more dependent clauses). Such sentences are often written to suggest that events or time are running together and hard to separate. However, such writing may more often suggest error than experiment, so be careful.

Another type of sentence variation is achieved through repetition of words, phrases, or sentences for emphasis. Repeated words and ideas suggest continuity of idea and theme, help meld ideas and paragraphs, and sometimes create rhythms that are pleasing to the ear. While refrain is a term more often associated with music, poetry, and sermons, it is a form of repetition that is quite powerful in prose as well. A refrain is a phrase or group of words repeated throughout a text to remind readers (or listeners) of an important theme. For example, the words “I have a dream” are a refrain from American activist Martin Luther King Jr. ’s (1929–1968) speech by the same name. Look at how Mark Twain uses repetition to increase the tension.

I seized the bell-rope; dropped it, ashamed; seized it again; dropped it once more; clutched it tremblingly once again, and pulled it so feebly that I could hardly hear the stroke myself.

Variation in sentence structure, established through such techniques as fragments, labyrinthine sentences, and repetition, creates certain effects within the text because each technique conveys its information in an unmistakable way. These techniques are stylistic devices that add an emotional dimension to the typically factual material of narrative prose without announcing, labeling, or dictating what those emotions should be. The wordplay of alternate-style composing allows narrative prose to convey themes more often conveyed through more obviously poetic forms. These sentence variations are a large component of what constitutes voice. For more information about sentence structure, see Clear and Effective Sentences.

Voice

As you write, focus on developing your voice, which in writing is the identity or personality of the narrator or writer. A writer’s voice is sometimes equated with an individual’s personal style—the elements that contribute to the way that person looks and acts. Do you favor certain kinds of clothing? Do you walk in a certain way? Do you have certain characteristic gestures or speech patterns? In writing, your voice is the sum total of the words you choose, the way you use them, the attitude you project by your word choice, the mood you create, the way your words describe characters, the way characters speak and behave, and the way you relate events. In personal writing, voice comes through via narration, dialogue, and characterization and the way you project your personality through them.

Further, writers often speak with more than one voice, or maybe with a single voice that has a wide range, varied registers, multiple tones, and different pitches. In any given composition, a writer may try to say two things at the same time. Sometimes writers question their own assertions, sometimes they say one thing aloud and think another silently to themselves, sometimes they say one thing that means two things, and sometimes they express contradictions, paradoxes, or conundrums.

Double voices in a text may be indicated by parentheses—the equivalent of an actor speaking an aside on the stage or in a film. In a film, the internal monologue of a character may be revealed as a voice-over or through printed subtitles while another reaction is happening on-screen. With text, you can change the type size or font or switch to italic, boldface, or CAPITAL LETTERS to signal a switch in your voice as a writer. The double voice can also occur without distinguishing markers at all or with simple paragraph breaks or spaces.

Effective voice can be achieved through sentence structure and word choices. Try to balance descriptive language and dialogue. You likely have heard the expression “Show, don’t tell.” Use narration to describe events, actions, and even the narrator’s thoughts, but don’t fall into the trap of feeling as though you need to describe everything. Allow events to flow naturally through the narration, weaving in action and dialogue. Precisely placed dialogue can reinforce the narration.

Because voice infuses personality into the composition, the lack of voice or a weak voice may make your story read like a timeline rather than selected events leading to a meaningful turning point. You want your voice to be consistent, reliable, and relatable to your readers. Often this voice will sound like you, infusing your personality or identity into the text. If you recreate authentic (or a good imitation of authentic) dialogue, narration, and description, your voice will likely be strongest, as it suggests a real connection with you.

Mood

When expressing the narrator’s emotions and point of view about the events of the text, voice is a major factor in creating mood (atmosphere). For example, a mood may be gloomy, happy, or tense. The same event told by a narrator with a casual, lighthearted voice can be read completely differently if narrated with a formal, argumentative voice. Consider these two sentences and the effect created by the word choice:

- The rain danced on the pavement, sparkling droplets falling from cotton balls above.

- The rain pounded the pavement, pouring buckets from thundering gray clouds above.

The mood in the first sentence reflects a positive disposition toward the rain. The second sentence, though it says nearly the same thing, shows a negative attitude, expressing the violence of the rain. The two distinct moods, developed through imagery, details, and language, influence the reader’s perception of the rain.

Conclusion and Reflection

At the end of your story, you will have the opportunity to reflect on the turning-point event, its impact on you, and perhaps its application to a universal theme. In the Twain example, the reflection is relatively straightforward.

“Very well, then. You shouldn’t have allowed me or anybody else to shake your confidence in that knowledge. Try to remember that. And another thing: when you get into a dangerous place, don’t turn coward. That isn’t going to help matters any.”

It was a good enough lesson, but pretty hardly learned. Yet about the hardest part of it was that for months I so often had to hear a phrase which I had conceived a particular distaste for. It was, “Oh, Ben, if you love me, back her!”

Twain uses Mr. Bixby’s words to teach both himself and readers the lesson. Twain’s reflection also points to a universal lesson, creating a relatable thread from which readers can learn. As you compose your reflection, ask yourself these questions:

- What have you learned from your turning point?

- What can readers learn from your turning point?

- How will you express this lesson?

You may reflect by using literary elements such as imagery or figurative language that help develop the theme or message. You will want to leave room for your readers’ own interpretations so that they can apply the lesson to their own lives, as Twain does. Certainly, most people have doubted their knowledge and abilities at some point, and Mr. Bixby’s directive “Don’t turn coward” has universal meaning.

Peer Review: Focus on Big-Picture Elements

After your first draft is complete, begin the process of peer review. In this initial review, peer reviewers should focus on big-picture elements, such as plot, point of view, organization, and reflection. Peer reviewers can use the following sentence starters to assess these elements.

- My first impression of the story is _________. From it, I learned _________.

- The story begins with/by _________. It could be made more engaging by _________.

- The author uses dialogue to _________.

- The narrative is organized by _________. Doing _________ could strengthen the organization.

- The author’s main point is _________ and is developed by _________.

- The author wants to tell me _________.

- I think these details could be made stronger to better develop the main idea or theme of _________.

In addition, peer reviewers may choose to mark the manuscript in the following ways:

- Circle unnecessary details. Underline places where more vivid details would bring events or ideas to life.

- Mark places where transitions are needed.

- Place quotation marks in the margin to indicate places where dialogue might better develop the story.

Revising: Let the Small Stuff Go for Now

After reading through your peer review, you now have the opportunity to revise your story. When you revising, reimagine your manuscript until it reaches your audience in the way you want it to. Begin this process by identifying the physical changes you want to make. These might include moving, adding, or deleting content and rewriting ideas. There are also nonphysical ways to revise. Focus on the big picture; think about whether the way you have told your story has delivered your intended message effectively. Avoid getting caught up in minute details before you have shaped the narrative to relate your intended ideas.

Use the following checklist to work through the revision process.

- Introduction: Does the introduction hook the reader and establish the background knowledge needed, including plot and setting?

- Sequence of events: Is the story told in a logical and consistent order?

- Vivid details: Do you provide vivid details that engage your readers’ senses?

- Tone and mood: Are the tone and mood effective for your purpose?

- Characterization, narration, and voice: Have you developed consistent and specific characterization through your narration and voice?

- Dialogue: Does the dialogue help move the plot and reflect the characters?

- Transitions: Have you used clear transitions and time signals to establish chronology and connect important ideas?

- Structure: Have you developed a cohesive structure, including varying sentence lengths and structures? Can you improve sentences by restructuring, combining, or separating them?

- Conclusion: Does your conclusion clearly explain the significance of the turning-point event, including its relationship to the theme you want to develop?