4.3: Glance at Genre- Conflict, Detail, and Revelation

- Page ID

- 134149

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify common formats and design features used to develop a personal narrative or memoir.

- Show that genre conventions are shaped by purpose, culture, and expectation.

In personal writing genres, you share experiences of your life, centering them on a specific theme or memory. Unlike an autobiography, which typically extends across an entire lifetime or at least a number of years, memoirs and personal narratives are shaped by a narrower focus, with more specific storytelling surrounding a time period or an event. When writing in these personal genres, authors seek to make an emotional connection with their audience to relate an experience, emotion, or lesson learned.

Characteristics of Memoirs and Personal Narratives

One way to approach a memoir or personal narrative is to think of it as a written series of photographs—snapshots of a period of time, moment, or sequence of events connected by a theme. In fact, writing prose snapshots is analogous to constructing and arranging a photo album composed of separate images. Photo albums, when carefully assembled from informational snapshots, tell stories with clear beginnings, middles, and endings. However, they show a lot of white space between one picture and the next, with few transitions explaining how the photographer got from one scene to another

In other words, while photo albums tell stories, they do so piecemeal, requiring viewers to fill in or imagine what happens between shots. You also might think of snapshots as individual slides in a slideshow or pictures in an exhibition—each the work of the same maker, each a different view, all connected by some logic, the whole presenting a story.

Written snapshots function in the same way as visual snapshots, each connected to the next by white space. Sometimes written snapshots can function as a series of complete and independent paragraphs, each an entire thought, without obvious connections or transitions to the preceding or following paragraph. White space between one snapshot and another gives readers breathing space, allowing them time to digest one thought before continuing to the next. It also exercises readers’ imaginations; as they participate in constructing logic that offers textual meaning, the readers themselves make connections and construct meaning. At other times, snapshots flow more directly, one after another, through chronological, circular, parallel, or other structures to move from event to event.

The secret to using snapshots successfully in your writing is to place them carefully in an order that conveys a theme and creates an unbreakable thread. And as with visual snapshots, writers must carefully choose which moments to include—and which to omit. Because they tell stories, memoirs and personal narratives share aspects of the fictional narrative genre. In writing them, you will use crafting tools to tell a vivid and purposeful story that takes into consideration your personal experience and the needs of your reader.

The Story Teller's Dilemma: Clarity of Action

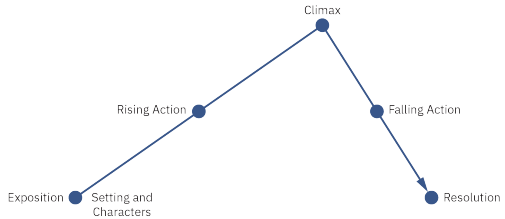

How you construct your story is as important as the story you choose to tell. Deciding on the most effective way the way to tell the story—that is, deciding what framework to use—helps you develop clarity of action to lead readers to the theme or message you seek to develop. Various components work together to bring clarity, but most often in a memoir or personal narrative, clarity comes from plot and character development. Narratives often follow a general structure called an arc to develop characters and plot and build the emotional impact of a story. Look at Figure \(4.4\) for an idea of what a story arc looks like.

Figure \(4.4\) Narrative arc (CC BY 4.0; Rice University & OpenStax)

This arc, also called a narrative arc or a plot triangle, is composed of the following elements:

- The exposition sets up the narrative. It introduces characters and setting and establishes the primary conflict of the story, allowing readers to learn the who, what, when, where, and why of the events that will unfold.

- Next, the rising action fully develops the conflict. This developed series of events, the longest part of the narrative, produces increasing tension that engages readers.

- The climax is the turning point of the narrative, in which the story reaches its highest point of tension and conflict. It is the moment when some kind of action must be taken.

- In the falling action, the conflict begins to be resolved, and the tension lessens.

- Finally, during the resolution, the conflict is resolved, and the narrative ends. In memoirs and personal narratives, the resolution often includes or precedes a reflection that examines the broader implications of the theme or lessons learned. Of course, as in real life, conflicts are not always resolved, but the narrator can still reflect on the outcome of the situation.

Although many narratives and memoirs follow this plot-driven arc, narratives can also focus on character arcs. Character-driven narratives explore an individual, most often the narrator, and their development. The stories focus on creating an emotional connection between the character and the reader. Both plot and character arcs may be, and often are, present in memoirs and personal narratives.

Regardless of whether the focus is on plot or characters, conflict is synonymous with the reason for telling your story—it is the driving force. Conflict is often the main challenge faced by a character, and it urges the story along by engaging readers through tension and encouraging them to keep reading. Without conflict, your memoir or personal narrative will lack an overall theme. The major conflict is the undercurrent that drives each scene and is often developed by an inciting incident. Introduced in the exposition and developed in the rising action, this incident sets the mood of the story and engages readers. After the story’s climax, where the conflict reaches its peak, the tension gradually resolves during the falling action and moves toward resolution, during which you can explicitly or implicitly explore the theme that ties the story elements together. Sometimes the resolution is accompanied by a revelation, in which the narrator or reader understands something about the bigger picture, such as a lesson learned from the events recounted or knowledge about the general human condition. Of course, each scene or section should have its own conflict, connected in some way to the overarching message of your writing. As you write, ask yourself, What’s the conflict? By identifying the conflict explicitly, you will ensure that it remains central to your narrative.

Two important aspects of plot structure regarding time in a memoir are chronos and kairos. Chronos is the sequence of events told according to their order. This order is often chronological and linear, but not always—it can be interrupted, fragmented, circular, or otherwise out of sequence and can sometimes include flashbacks. Chronos develops themes by the telling of events. Kairos, on the other hand, is the Greek concept of timeliness. Events told through the lens of kairos are often transcendental, an argument that is made at the right time, often rooted in a cultural moment or movement.

Other important aspects of personal writing overlap with the narrative genre. Both reader engagement and plot rely largely on vivid details and sensory descriptions to move readers through the story. For more information on narrative elements that may enhance your personal narrative or memoir, revisit Literacy Narrative: Building Bridges, Bridging Gaps.

Key Terms for Memoir or Personal Narrative Writing

- Anecdotes: a short, interesting story or event told to demonstrate a point or amuse the audience.

- Bias: the inclusion or exclusion of certain events and facts, the decisions about word choice, and the consistency of tone. All work together to convey a particular feeling or attitude. Bias comes from a specific stance or worldview and can limit a text, particularly if that bias is left unexamined.

- Characters: fictional people (or other beings) created in a work of literature. The narrator of a memoir or personal narrative is the nonfiction equivalent of the main character.

- Climax: the point of highest level of interest and emotional response in a narrative.

- Conclusion: in narrative writing, the resolution. It is the point at which the narrator has reached a decision.

- Conflict: the major challenge that the main character faces.

- Doubling: a mirroring of events, objects, characters, or concepts in a memoir.

- Exposition: the beginning section of a narrative that introduces the characters, setting, and plot.

- Falling action: the section of the plot after the climax in which tension from the main conflict is decreased and the narrative moves toward the conclusion, or resolution.

- Flashback: a scene that interrupts the chronological order of the main narrative to return to a scene from an earlier time.

- Foreshadowing: hints of what is to come in the text.

- Mood: the atmosphere of the text, often achieved through details, description, and setting.

- Plot: the events that make up a narrative or story.

- Point of view: the perspective from which a narrative is told. Memoirs and personal narratives usually use the first-person point of view, or tell the story through the eyes of the narrator.

- Resolution: the point at which a story’s conflict is settled; the conclusion of a narrative.

- Revelation: a discovery about a person, event, or idea that shapes the plot.

- Rising action: a series of events in the plot in which tension surrounding the major conflict increases and the plot moves toward its climax.

- Setting: when and where a narrative occurs. Setting is revealed through narration and details.

- Theme: the underlying idea that reveals the author’s message about a narrative.

- Vivid details: sensory language and detailed descriptions that help readers gain a deeper and fuller understanding of ideas and events in the narrative.

- Voice: the combination of vocabulary, tone, sentence structure, dialogue, and other details that make a text authentic and engaging. Voice is the “identity” or “personality” of the writer and includes the specific English variety used by the narrator and characters.