8.3.6: Paintings from the Tomb-chapel of Nebamun

- Page ID

- 163343

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The fragments from the wall painting in the tomb-chapel of Nebamun are keenly observed vignettes of Nebamun and his family enjoying both work and play. Some concern the provision of the funerary cult that was celebrated in the tomb-chapel, some show scenes of Nebamun’s life as an elite official, and others show him and his family enjoying life for all eternity, as in the famous scene of the family hunting in the marshes. Together they decorated the small tomb-chapel with vibrant and engaging images of an elite lifestyle that Nebamun hoped would continue in the afterlife.

Hunting in the marshes

Nebamun is shown hunting birds from a small boat in the marshes of the Nile with his wife Hatshepsut and their young daughter. Such scenes had already been traditional parts of tomb-chapel decoration for hundreds of years and show the dead tomb-owner “enjoying himself and seeing beauty,” as the hieroglyphic caption here says.

This is more than a simple image of recreation. Fertile marshes were seen as a place of rebirth and eroticism. Hunting animals could represent Nebamun’s triumph over the forces of nature as he was reborn. The huge striding figure of Nebamun dominates the scene, forever happy and forever young, surrounded by the rich and varied life of the marsh.

There was originally another half of the scene which showed Nebamun spearing fish. This half of the wall is lost, apart from two old photographs of small fragments of Nebamun and his young son. The painters have captured the scaly and shiny quality of the fish.

A tawny cat catches birds among the papyrus stems. Cats were family pets, but in artistic depictions like this they could also represent the Sun-god hunting the enemies of light and order. His unusual gilded eye hints at the religious meanings of this scene.

The artists have filled every space with lively details. The marsh is full of lotus flowers and Plain Tiger butterflies. They are freely and delicately painted, suggesting the pattern and texture of their wings.

Nebamun’s Garden

Nebamun’s garden in the afterlife is not unlike the earthly gardens of wealthy Egyptians. The pool is full of birds and fish, and surrounded by borders of flowers and shady rows of trees. The fruit trees include sycamore-figs, date-palms and dom-palms—the dates are shown with different degrees of ripeness.

On the right side of the pool a goddess leans out of a tree and offers fruit and drinks to Nebamun (now lost). The artists accidentally painted her skin red at first but then repainted it yellow, the correct color for a goddess’ skin. On the left, a sycamore-fig tree speaks and greets Nebamun as the owner of the garden; its words are recorded in the hieroglyphs.

Here the pool is shown from above, with three rows of trees arranged around its edges. The waves of the pool were painted with a darker blue pigment; much of this has been lost, like the green on the trees and bushes.

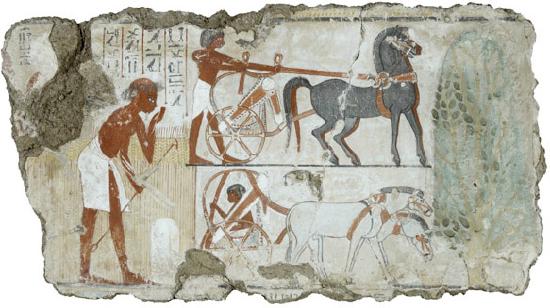

Surveying the fields

Nebamun was the accountant in charge of grain at the great Temple of Amun at Karnak. This scene from his tomb-chapel shows officials inspecting fields. A farmer checks the boundary marker of the field.

Nearby, two chariots for the party of officials wait under the shade of a sycamore-fig tree. Other smaller fragments from this wall are now in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, Germany and show the grain being harvested and processed.

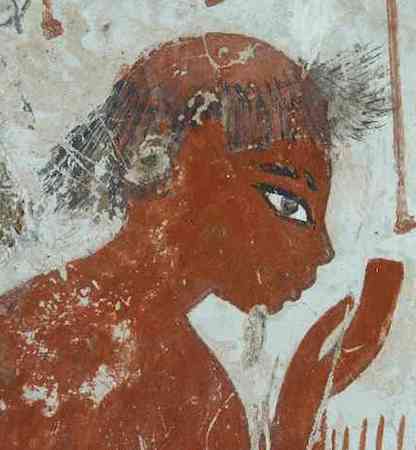

The old farmer is shown balding, badly shaven, poorly dressed, and with a protruding navel. He is taking an oath saying: “As the Great God who is in the sky endures, the boundary-stone is exact!”

“The Chief of the Measurers of the Granary,” (mostly lost) holds a rope decorated with the head of Amun’s sacred ram for measuring the god’s fields. After Nebamun died, the rope’s head was hacked out, but later, perhaps in Tutankhamun’s reign, someone clumsily restored it with mud-plaster and redrew it.

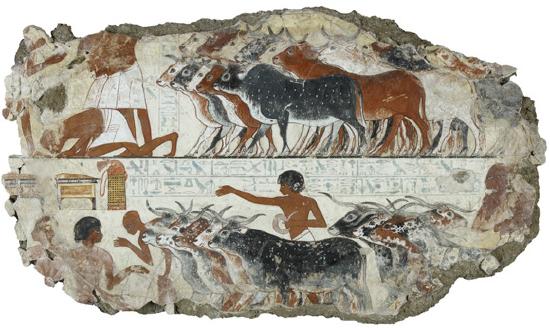

Nebamun’s cattle

This fragment is part of a wall showing Nebamun inspecting flocks of geese and herds of cattle. Hieroglyphs describe the scene and record what the farmers say as they squabble in the queue. The alternating colors and patterns of cattle create a superb sense of animal movement.

The herdsman is telling the farmer in front of him in the queue:

Come on! Get away!

Don’t speak in the presence of the praised one!

He detests people talking ….

Pass on in quiet and in order …

He knows all affairs, does the scribe and counter of grain of [Amun], Neb[amun].

The name of the god Amun has been hacked out in this caption where it appears in Nebamun’s name and title. Shortly after Nebamun died, King Akhenaten (1352–1336 B.C.E.) had Amun’s name erased from monuments as part of his religious reforms.

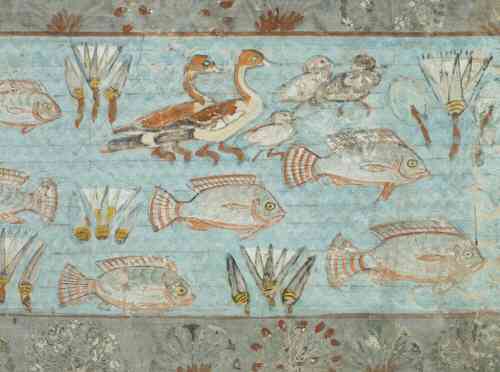

Nebamun’s geese

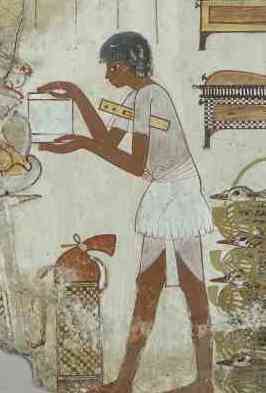

This scene is part of a wall showing Nebamun inspecting flocks of geese and herds of cattle. He watches as farmers drive the animals towards him; his scribes (secretaries) write down the number of animals for his records. Hieroglyphs describe the scene and record what the farmers say as they squabble in the queue.

This scribe holds a palette (pen-box) under his arm and presents a roll of papyrus to Nebamun. He is well dressed and has small rolls of fat on his stomach, indicating his superior position in life. Beside him are chests for his records and a bag containing his writing equipment.

Farmers bow down and make gestures of respect towards Nebamun. The man behind them holds a stick and tells them: “Sit down and don’t speak!” The farmers’ geese are painted as a huge and lively gaggle, some pecking the ground and some flapping their wings.

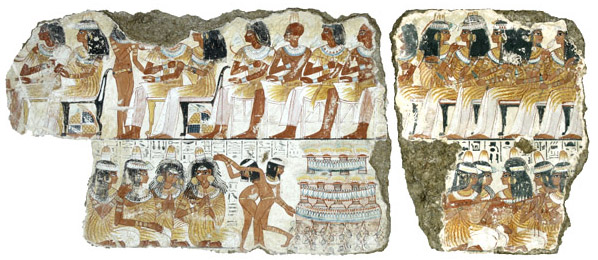

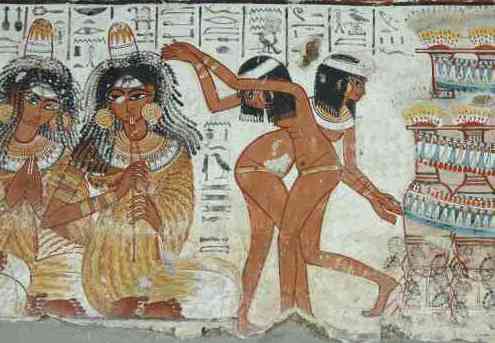

A feast for Nebamun (top half)

An entire wall of the tomb-chapel showed a feast in honor of Nebamun. Naked serving-girls and servants wait on his friends and relatives. Married guests sit in pairs on fine chairs, while the young women turn and talk to each other. This erotic scene of relaxation and wealth is something for Nebamun to enjoy for all eternity. The richly-dressed guests are entertained by dancers and musicians, who sit on the ground playing and clapping. The words of their song in honor of Nebamun are written above them:

The earth-god has caused

his beauty to grow in every body…

the channels are filled with water anew,

and the land is flooded with love of him.

Some of the musicians look out of the paintings, showing their faces frontally. This is very unusual in Egyptian art, and gives a sense of liveliness to these lower-class women, who are less formally drawn than the wealthy guests. The young dancers are sinuously drawn and are naked apart from their jewelry.

A rack of large wine jars is decorated with grapes, vines and garlands of flowers. Many of the guests also wear garlands and smell lotus flowers. All the guests wear elaborate linen clothes. The artists have painted the cloth as if it were transparent, to show that it is very fine. These elegant sensual dresses fall in loose folds around the guests’ bodies.

Men and women’s skins are painted in different colors: the men are tanned and the women are paler. In one place the artists altered the drawing of these wooden stools and corrected their first sketch with white paint.

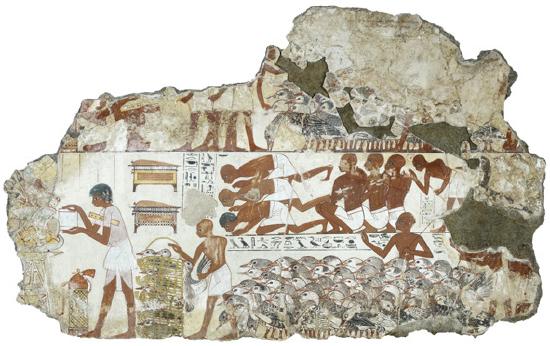

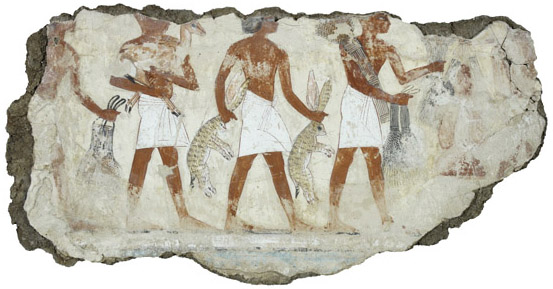

Servant’s bringing offerings

A procession of simply-dressed servants bring offerings of food to Nebamun, including sheaves of grain and animals from the desert. Tomb-chapels were built so that people could come and make offerings in memory of the dead, and this a common scene on their walls. The border at the bottom shows that this scene was the lowest one on this wall.

One servant holds two desert hares by their ears. The animals have wonderfully textured fur and long whiskers. The superb draughtsmanship and composition make this standard scene very fresh and lively.

The artists have even varied the servants’ simple clothes. The folds of each kilt are different. With one of these kilts, the artist changed his mind and painted a different set of folds over his first version, which is visible through the white paint.

Suggested readings:

M. Hooper, The Tomb of Nebamun (London, British Museum Press, 2007).

R. Parkinson, The painted Tomb-chapel of Nebamun (London, British Museum Press, 2008).

A. Middleton and K. Uprichard, (eds.), The Nebamun Wall Paintings: Conservation, Scientific Analysis and Display at the British Museum (London, Archetype, 2008).

Explore the tomb-chapel of Nebamun in a 3D interactive animation at The British Museum

© Trustees of the British Museum