2.8: The François Tomb

- Page ID

- 163464

The François Tomb is chock-full of elaborate frescoes with complicated messages we may never fully understand.

When Alessandro François and Adolphe Noël des Vergers entered the so-called François Tomb (named for its discoverer) in 1857, they described a magnificent treasure trove in which ancient Etruscan warriors were sleeping on their funeral couches, surrounded by grave goods, armaments, and brilliant tableaux on painted walls. This exceptional tomb from the Ponte Rotto necropolis in Vulci served as a familial burial monument and was used for several centuries in the Hellenistic period.

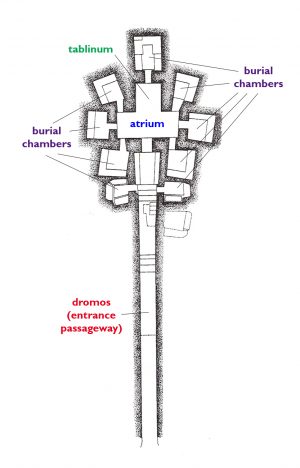

The Etruscans believed that the afterlife mirrored their own world, so they provided elaborate “homes” for their dead. The ground plan of the François Tomb is essentially a T shape, with two main chambers (called the atrium and tablinum after the rooms of typical Italo-Roman houses). The main chambers are arranged perpendicularly, with small burial chambers branching out from all sides.

The François Tomb is famous largely because of the frescoes of its main chamber, which can be dated to the fourth century B.C.E. Unlike most Etruscan tomb paintings, the François tomb frescoes seem to include battle scenes — making it a rare, early example of ancient history painting.

Though scholars still have many questions surrounding the exact meanings of these paintings, they reflect important Etruscan ideas about history, and they would have helped reinforce shared narratives about ancestry and the past as family members continually visited the tomb to inter the newly deceased.

Dazzling frescoes

Frescoes fill the walls and ceiling of the tomb. (The original frescoes were removed by a collector in the 19th century, and replaced in the tomb itself by reproductions.) The ceiling is designed to look like the interior of a building with a timber-framed roof structure, while the walls include various figural representations and geometric designs.

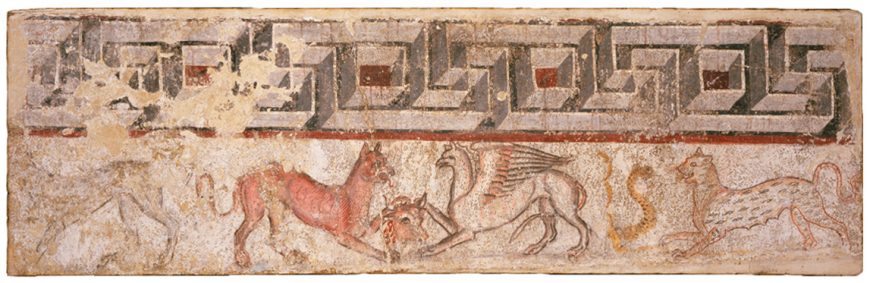

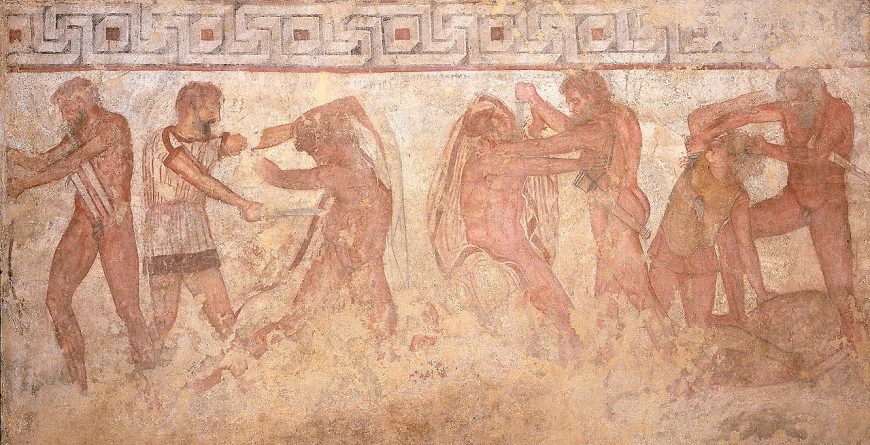

The atrium, which was the first room a visitor would enter, has the most elaborate frescoes. At the upper margin of the wall, there is a small running frieze in two registers: a Greek key pattern on top, with a hunting scene below. Under the hunting scene are larger scenes featuring human figures depicted at nearly life size.

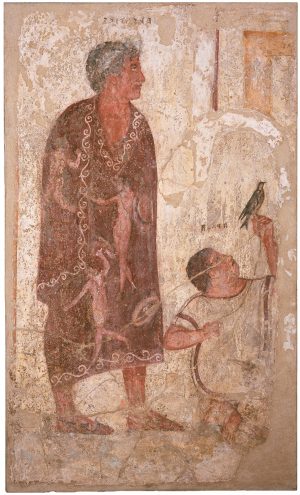

Although one wall was badly damaged, most of the figures are well-preserved and labeled with text. From this text we know that these figures include a mix of mythological characters (including Sisyphus, Eteocles and Polynices killing each other, and Ajax raping Cassandra) and historical figures, including the founder of the tomb, an Etruscan aristocrat named Vel Saties. This full-length portrait of Vel Saties wearing a toga picta has garnered acclaim as the first such portrait in western art.\(^{[1]}\) It is likely that the lowest quarter of the wall was obscured by stone benches, although not all of these benches have been preserved.

Scenes from mythology and history

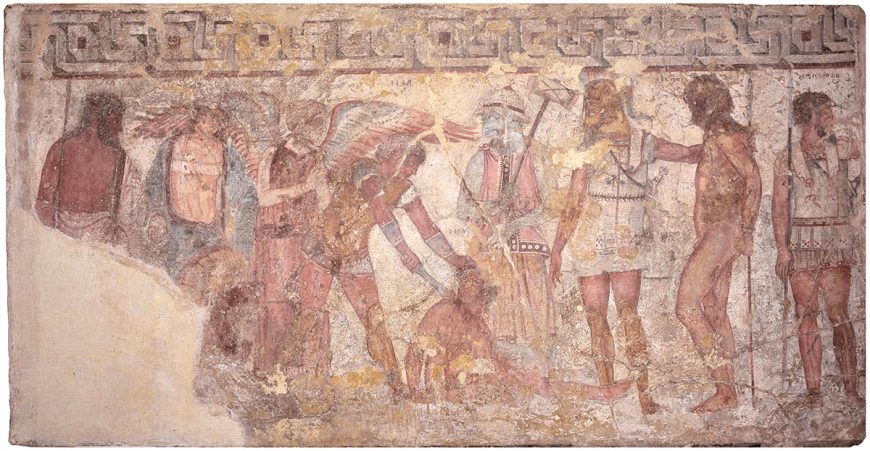

The tablinum, or rear room of the tomb, also has benches at the bottom, a fresco representing a running meander at the top, and a scene featuring human figures in between. There are a few differences in the iconography that clearly separate the atrium and tablinum. First, the tablinum does not have a hunting scene below the meander; second, the ceiling patterns are different; and finally, the figural fresco is made up of two narrative scenes, each with labeled characters.

On the left-hand side of the tomb, there is a scene of Achilles sacrificing Trojan prisoners to the shade of Patroclus.

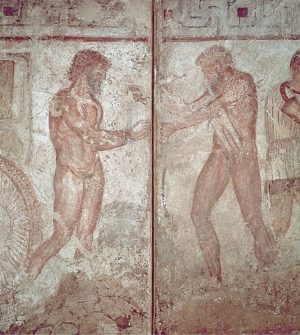

The right-hand side of the tomb shows a battle between two groups of Etruscans. It is this battle scene that has drawn the majority of historical attention. The figures are arranged into a series of dueling pairs on the long wall. Inscriptions identify the men on both sides as Etruscan, but only the figures who appear to be losing are identified with a specific city. This discrepancy has led scholars to believe that the winners are from Vulci. Because many of the dying men are only partially clothed, this scene has been interpreted as a nocturnal ambush: surprised in their sleep, the defeated figures were apparently not able to fully dress before the fighting started.

A link between text and image

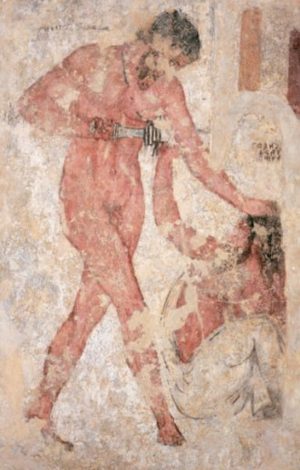

Rounding the corner of the fresco is a scene derived from Rome’s legendary history. Mastarna (perhaps an alternate name for Servius Tullius, the legendary sixth king of Rome) frees Caelius Vibenna, an Etruscan aristocrat who aided Rome’s founder Romulus in his wars against Titus Tatius. Although these two men are portrayed nude (in the manner of mythological figures) there is some evidence that both were considered historical figures.

These paintings represent an important potential link between ancient visual and textual sources. The Roman emperor Claudius claimed in a speech that Mastarna was the Etruscan name of Rome’s sixth king, Servius Tullius, who was a friend of Caelius Vibenna (ILS 212). This is very similar to what is portrayed in the frescoes in the François tomb, and so the tomb’s iconography seems to provide independent confirmation of Claudius’ account.

Many scholars interpret the tomb’s iconography as being pro-Etruscan and anti-Roman. Since the Roman state made substantial territorial conquests in Etruria during the fourth century B.C.E., when the tomb was founded, the deployment of the iconography of Caelius Vibenna and Mastarna could have been a symbol of cultural pride among the Etruscans.

Unanswered questions

Despite widespread agreement about the fresco of Mastarna and Caelius Vibenna, questions remain about the meaning of many of the other frescoes in the François tomb.

The atrium fresco depicts Camillus killing a figure identified as “Gaius Tarquinius of Rome.”

While both Camillus and Tarquinius are figures from early Roman history, their presence in the painting is not clearly understood. The name Tarquinius may refer to either of two male Tarquin rulers (or Tarquinii) from early Roman history; however, their first names were not Gaius, but Lucius, and neither of these men was killed by Camillus. Both Tarquinii lived around the time of Mastarna in the 6th century B.C.E., whereas Roman authors believed that Camillus lived about a century later, closer in time to the date of the tomb’s construction. To further complicate things, according to Roman tradition, Camillus was famous for defeating Etruscans. His presence in the tomb and his killing of Tarquinius are thus both mysterious.

Scholarly opinion is also divided on the relationship between the Camillus/Tarquinius fresco and the other historical fresco. Many scholars see them as part of the same narrative; others, however, argue that the two must be kept separate. This debate is unlikely to be resolved unless new evidence is discovered.

Mysteries remain

The François Tomb is rightly celebrated for its elaborate decor. Although we cannot fully understand the choices made by the tomb’s patron, it seems likely that the frescoes were created to deliver a specific message. This message may have been political (pro-Etruscan/anti-Roman), religious (since most scenes focus on bloodshed), familial (portraying the family history of the owners), or ethical (illustrating moral qualities that were important to the owners). All of these interpretations have been suggested, and it is possible that all of them are correct—that is, that the owner of the tomb had all of these aspects in mind when choosing the iconography. It is the historical fresco, however, that has captured the most interest, as it seems to preserve rare information about Etruscan historical thought.

We may never know the answers to many of these questions, but the François Tomb remains a shining example of Etruscan fresco painting that offers us a glimpse into the tumultuous history of the ancient Mediterranean world.

\(^{[1]}\)See Lisa C. Pieraccini, “Etruscan Wall Painting: Insights, Innovations, and Legacy” in Sinclair Bell and Alexandra A. Carpino, A Companion to the Etruscans (John Wiley & Sons, 2016), p. 256.

Additional resources:

The François Tomb at the Southern Etrurian Archaeological Heritage website (in Italian)

Vulci Park website with image gallery

B. Andreae, “Die Tomba François. Anspruch und historische Wirklichkeit eines etruskischen Familiengrabes.” In B. Andreae, A. Hoffman, C. Weder-Lehman (eds.), Die Etrusker: Luxus für das Jenseits. (Munich: Hirmer, 2004), pp. 176-207.

L. Bonfante Warren,“Roman Triumphs and Etruscan Kings.” The Journal of Roman Studies 60 (1970), pp. 49-66.

F. Buranelli and S. Buranelli, La Tomba François di Vulci. (Rome: Quasar, 1987).

F. Coarelli, F. “Le pitture della tomba François a Vulci : una proposta di lettura.” Dialoghi di Archeologia 3 (1983), pp. 43-69.

T. J. Cornell, The Beginnings of Rome (London: Routledge, 1995), pp. 135-141.

M. Cristofani, “Ricerche sulle pitture della tomba François di Vulci. I fregi decorativi,” Dialoghi di Archeologia 1 (1967), pp. 189-219.

N. T. de Grummond, Etruscan Myth, Sacred History, and Legend. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum, 2006), pp. 175-180, 197-199.

Jean Gagé, “De Tarquinies à Vulci : Les guerres entre Rome et Tarquinies au IVe siècle avant J.-C. et les fresques de la « Tombe François »” Mélanges d’archéologie et d’histoire publié par l’Ecole française de Rome 74 (1962), pp. 79-122.

Peter J. Holliday, “Narrative structures in the François tomb,” in Narrative and event in ancient art, (Cambridge, 1988), pp. 175-197.

A. Hus. Vulci Étrusque et Étrusco-Romaine. (Paris: Klincksieck, 1972).

Jaclyn Neel, Early Rome: Myth and Society (Wiley, 2017).

Jaclyn Neel, “The Vibennae: Etruscan Heroes and Roman Historiography” Etruscan Studies 20.1:1-34.

A. Sgubini Moretti (ed), Eroi Etruschi e Miti Greci. (Rome: Soprintendenza per i beni archeologici dell’Etruria meridionale, 2004).