Art is a conversation with time

Essay by Dr. Bryan Zygmont

John Trumbull’s The Declaration of Independence (1817-18)—perhaps his most enduring and important work—has appeared in countless history textbooks, and in this way, American students of all ages have been led to believe that there was a magical day on the Fourth of July in 1776 when delegates gathered together at Independence Hall to sign this foundational document in the history of the United States. But paintings do not necessarily tell the truth, and Trumbull’s masterpiece is no exception. The Declaration of Independence was not formally signed on the Fourth of July (as yearly commemorative fireworks might suggest), and not all 56 men who would eventually sign the Declaration were present when it was officially autographed some weeks later.

There is another whispered untruth in this painting. Trumbull has depicted 47 people in this somewhat confined space, 42 of whom were delegates who (eventually) would sign the Declaration of Independence. Each representative Trumbull painted is a white male, which makes this group far from representational of the population of the each colony they represented (the American colonies were far more pluralistic). The same has been true of the United States in all the decades that followed. “We the People” are both men and women, both native born and recently arrived, and look both similar to and distinct from the 47 landholders in Trumbull’s painting. The broad history of art in North America makes this succinctly clear. In that art we can get a more true sense of what the United States of America was in the past and what the United States of America is today.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Robert W. Weir, Embarkation of the Pilgrims, 1844, oil on canvas, 548 cm x 365 cm (U.S. Capitol)

The Puritans — less dour than you might suspect!

But it is not only in regards to the signing of the Declaration of Independence that history textbooks might deceive high school students. In fact, if one can conjure up a mental image of what a seventeenth-century pilgrim might look like, that image would likely include joyless facial expressions and austere clothing that did not stray from black and white—for this is the somewhat romanticized view that nineteenth-century artists would later present (Robert Weir’s The Embarkation of the Pilgrims is but one example). But although the Puritans fled England and then Holland in search of religious liberty, they were not as dour as historical lore might suggest. Indeed, as the Freake Portraits (1671-74) make clear, the Puritans were far more colorful and extravagant than our history books might indicate. This is true of their dress and attire, and it is equally as true as it pertains to their home furnishings.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Court Cupboard, 1665-73, red oak with cedar and maple (moldings), northern white cedar and white pine, 142.6 x 129.5 x 55.3 cm (Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art)

A Court Cupboard (c. 1665-73) in the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art aptly illustrates this important point. This particular cupboard was owned by Thomas Prence. Prence arrived in Plymouth Colony in what is now Massachusetts in November 1621, some 12 months after the Mayflower first brought Puritans to the New World. Pence was clearly a man of some talent and ability. He first served as Governor of Plymouth Colony from 1634-35 while still in his early 30s. He again served a short term from 1638-39, and then a much longer term from 1657 until is death in 1673.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Lathe-turned column, and doors decorated with spindles, Court Cupboard, 1665-73, red oak with cedar and maple (moldings), northern white cedar and white pine, 142.6 x 129.5 x 55.3 cm (Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art)

This cupboard is architectural in its mass and form and shows the ways in which domestic furniture made in the American colonies during the seventeenth century was influenced by European architecture. When looking at this object, for example, one can see various architectural elements. The topmost edge resembles a cornice and the open space underneath that cornice has the appearance of a kind of ionic frieze. Immense lathe-turned columns appear on the upper left and right edges, and twenty engaged columns—here called spindles—decorate the front.

The patina of time has changed the color of this object, but when first made it would have appeared red, black and vibrant yellow. In total, this object suggests opulence far more than austerity. But this wealth is indicated not only by the object—its size, its decoration, its form—but also by what Prence and his wife would have placed both within and upon it. Without doubt, one of the reasons to own such a cupboard would be to display and store items of luxury, and we can well imagine silver plate displayed atop the cupboard and fine textiles in the drawers.

But this display of opulence—both in this extravagant piece of furniture and the luxury items it was meant to display and contain—does not only comment on Prence’s wealth, but also upon his blessedness. As a Puritan, Prence was a firm believer in the concept of predestination, the idea that he had—from birth—been selected for heavenly salvation. And because God was omnipotent (that is, all powerful) the wealth that Prence and his family enjoyed was clearly a signifier of God’s favor. For the Puritans, then, the tasteful display of wealth (be it clothing, jewelry, or furniture) was a material representation of their own goodness and God’s divine esteem.

A peaceable kingdom?

As one of the governors of Plymouth Colony during the seventeenth century, Prence was forced to deal with those who were in the New World before the arrival of the Puritans—Native Americans—and those who would follow—the Quakers. The historical record suggests that he was far kinder to the former than the latter, but these two groups—the Quakers and Native Americans—serve as the primary subjects for Edward Hick’s most popular subject, The Peaceable Kingdom (1826). In total, Hick’s—who was a member of the Society of Friends (Quakers) himself—painted more than five dozen versions of this subject, but the one in Philadelphia Museum of Art is interesting for the ways in which the artist included text into the borders of the image. Together, the text and image eloquently speak to the religious toleration the Quakers hoped to preach and practice in Pennsylvania, a toleration they had not found when they first settled in Massachusetts.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): Edward Hicks, The Peaceable Kingdom, 1826, oil on canvas, 83.5 x 106 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

On the right we can see a young boy—so young, in fact, that he wears what appears to be a dress as he has not yet been “breeched” to wear pants—standing astride and with his left arm around an adult (if diminutive) lion. A leopard and wolf join the lion as predators in this implausible garden, seemingly at peace with the docile ox, sheep, and lamb. The text on the left, top, and right reference a passage from the Book of Isaiah (11: 1-9) in the Jewish Bible and speaks to what our own earthly world would be like if the peace of Heaven could be found on earth.

If most of the text on the border references the Bible, the text on the bottom—When the great PENN his famous treaty made With indian chiefs beneath the Elm-tree’s shade—is decidedly secular. This text makes specific reference to the treaty William Penn signed with the Lenni Lenape (sometimes called the Delaware) Indians. In order to visually represent this, Hicks has depicted the mighty elm tree and a group of Quakers and Native Americans negotiating the treaty that bears Penn’s name. Hicks makes clear that Penn’s motives and intentions with the peoples who already occupied the land of what would become Pennsylvania were noble and good.

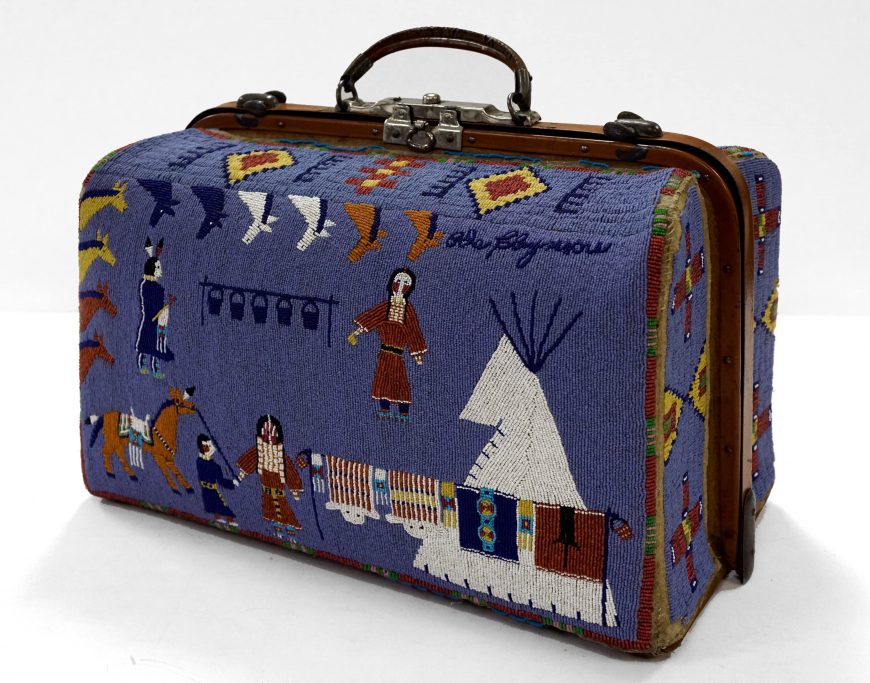

A beaded Lakota suitcase

But few of the interactions the new (European) arrivals had with longstanding (Native American) residents were so noble and good, and we are reminded of this in a beaded suitcase Nellie Two Bear Gates made and likely presented to her cousin, Ida Claymore. The artist was a member of the Lakota, who primarily lived in the Standing Rock area of North and South Dakota.

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): Nellie Two Bear Gates, Suitcase, 1880-1910, beads, hide, metal, oilcloth, thread (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

Gates has decorated the valise on both sides in a way that was traditional to the Lakota people. The abstract patterns that decorate the valise are artistic elements that go back centuries, but the artist has also introduced figural elements that provide a narrative. In the lower part of the object, for example, a woman stands wearing a red dress with a white breastplate; this is presumably the bride. To her left hang a variety of decorated bags, two beautifully embellished buffalo hides, a trade cloth, and another robe. These objects—which suggest the wealth of the bride—are items she brought to her marriage. On the upper part of the valise we can clear see the bride’s father on the left and her mother on the right. The pails that hang from the rail between them suggest the sumptuous feast that would commemorate the wedding.

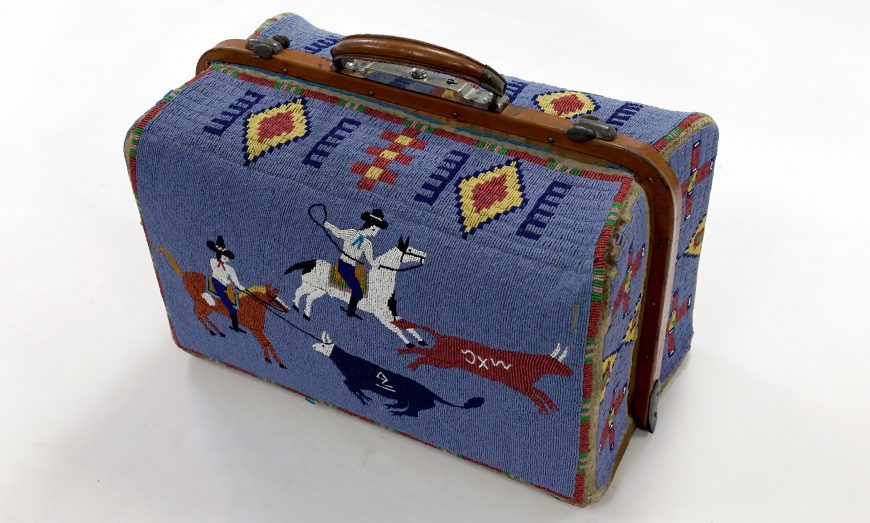

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): Nellie Two Bear Gates, Suitcase, 1880-1910, beads, hide, metal, oilcloth, thread (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

If the front of the valise shows a happy event, the obverse shows one that is much more somber when it is considered within the framework of Lakota life. On it we see two Lakota men riding horses. One has already lassoed a branded bull, while another has raised his right arm and is set to capture the bull that gallops from left to right. Although this may at first seem to be a scene—like the other—that captures an element of every day Lakota life, there is something more somber at issue. The Lakota’s centuries old nomadic life ways came to an end during the final quarter of the nineteenth century when they were forced onto reservations. This forced relocation was in part a result of the destruction of the resource that the Lakota depended upon for their nomadic existence: the American bison. In this way, the narrative on the suitcase signifies an important shift in the Lakota way of life, from a nomadic one that followed the bison, to a confined, government-mandated way of life dependent upon cattle for sustenance.

Coney Island and leisure

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): Reginald Marsh, Wooden Horses, 1936, tempera on board, 61 x 101.6 cm (Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art)

More than a thousand miles from the tragedy at Standing Rock Reservation, Americans delighted in the meteoric rise of Coney Island at the southern end of the borough of Brooklyn. Three competing amusement parks—Steeplechase Park, Luna Park, and Dreamland—opened between 1897 and 1904, and entertained the millions who came to visit. If at first Coney Island was a resort for the well to do, in the decades that followed it was venue where all different classes could mix and mingle regardless of race, gender, or socioeconomic status. At the height of the Great Depression, Coney Island was known as the Nickel Empire. A hotdog, a soda, and an excursion on one of the many rides all cost five cents (five cents in 1935 roughly equates to $.93 in 2019). Because of inexpensive nature of a trip to Coney Island, it attracted people of all walks of life who could collectively gather and forget—for a time—the hardships brought on by the economic crisis that then enveloped the world.

The artist, Reginald Marsh was keenly interested in depicting the vibrant nature of city life, and his painting, Wooden Horses (1936), captures this energy. A Parisian by birth but a New Yorker by choice, Marsh is remembered today for his energetic, vibrant use of primary colors and line, and for the fact that he used tempera—pigment mixed with egg yolk—rather than the more common oil paint. In this image, we can see many figures who all ride—sometimes by themselves or in other instances in tandem—on extravagantly carved wooden horses on an attraction meant to mimic the speed and thrill of a steeplechase race.

At first glance this may seem to be a painting that captures the exhilaration of the ride, but upon further reflection, there are elements that may prompt a sense of unease. For example, the artist—at least to our modern eyes—seems to objectify the women in a way that was rather typical at the many dance halls that were a part of men’s Coney Island experiences. Their racy attire, bright lipstick, and their straddling of the horse (rather than sitting in side-saddle fashion) all suggest a certain bawdiness. The pair in middle are particularly interesting. He—a self portrait of the artist a generation or so older than she—sits on the hind end of the carved equine and wraps his arms around her bodice. She—seemingly indifferent to his advances—focuses on the ride while the forward motion of her steed flutters her skirt, showing a not insignificant amount of her thigh.

Remembering Nazi Germany

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): George Grosz, Remembering, 1937, oil on canvas, 71.2 x 91.76 cm (Minneapolis Institute of Art, © Estate of George Grosz)

Although George Grosz painted Remembering (1937) only one year after Marsh completed Wooden Horses, the tone he captures could not be more different. Grosz was born in Berlin and immigrated to the United States in 1933 after spending the summer before in New York City teaching at the Art Students League. His departure from Germany preceded—by less than a month—Adolph Hitler’s mercurial rise to power when he was appointed chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933. Grosz, of course, was familiar with Hitler and his ambitions, and had spent considerable effort in the 1920s using his art as a way to ridicule German political leadership. As early as 1923, for example, Grosz had drawn caricatures of Hitler. Given the ways in which he had used his art to criticize the government, the artist knew it was best to escape far beyond the Nazi’s reach. Grosz remained in the United States for much of the rest of his life, though he did venture back to Europe on occasion.

One such trip was a brief return in 1935. If Grosz dreaded what fascist Germany was becoming when he immigrated to the United States in 1932, this subsequent visit confirmed his worst fears. Remembering is a product of that visit and the realization that the country of his birth had been completely swept up in an ideology of hate. In the painting, Grosz has painted his own likeness on the figure in the left foreground, and he sits in what looks to be a ruined building. A men’s jacket has been draped over his shoulders, but his arms cross his chest while the arms of the jacket lifelessly hang at his side. The worried look suggests he is aware of the chaos that surrounds him, but has turned his back to that bedlam. When Grosz escaped to the United States in 1933, he brought his wife and two sons with him, but his extended family and countless friends were forced to endure the atrocities that Hitler brought to the German people and to the world. One can imagine the guilt he felt at leaving loved ones behind.

As an artist, Grosz part of something significant about the United States during the second quarter of the twentieth century, namely the mass exodus of talented men and women from Europe to the United States who sought to escape the totalitarian regimes that were coming to power. These people arrived with dreams and aspirations of finding a better life in the United States. In addition to receiving the liberty they were seeking, they enriched their adopted country and the communities in which they lived, contributed to the Melting Pot—the e pluribus unum—that the United States has always been.

The AIDS epidemic

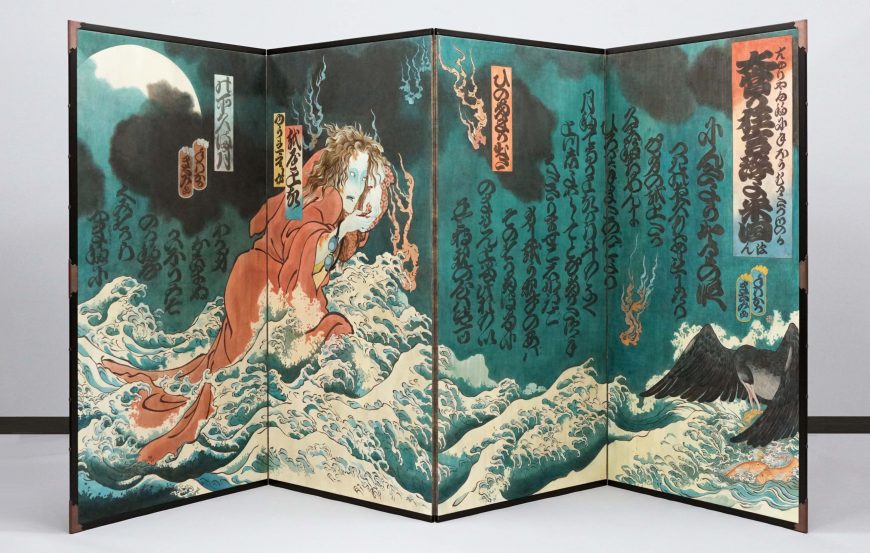

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\): Masami Teraoka, American Kabuki (Oishiiwa), 1986, watercolor and sumi ink on paper mounted on a four-panel screen, 196.9 x 393.7 x 3 cm (de Young Museum, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco), © Masami Teraoka

Although born in the Hiroshima Prefecture of Japan prior to the beginning of World War II, Masami Teraoka moved to the United States in 1961. His mature artistic style of the 1980s engages contemporary events within the framework of traditional Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints. The genre of ukiyo-e flourished in the 18th and 19th centuries in Japan. Ukiyo-e works draw their subject matter from popular theater (Kabuki), and urban life—especially the streets of Edo (Tokyo).

Although at first glance Teraoka owes an aesthetic debt to the great printmaker Hokusai and his iconic The Great Wave of Kanagawa (c. 1830), American Kabuki is different in many regards. Hokusai’s ukiyo-e print measures about 10” x 15”, while Teraoka’s colossal screen measures 6’5” x 12’10”. While The Great Wave is a small, almost intimate seascape with boats before Mount Fuji, the scale of American Kabuki is so large that it almost surrounds the viewer. And this enormity of scale forces the viewer to not only to address the landscape, but the horror that the landscape contains. The date—1986—is of paramount importance, for it was in the middle of the 1980s when America—and the entire world—came to more fully understand the horrors of the AIDS epidemic.

Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\): Katsushika Hokusai, Under the Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa oki nami ura), also known as The Great Wave, from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei), c. 1830-32, polychrome woodblock print; ink and color on paper, 10 1/8 x 14 15 /16″ / 25.7 x 37.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

First published in 1987—the year after Teraoka’s painting—Randy Shilts’s And the Band Played on: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic astutely chronicles the early years of this health tragedy. Although the terms were often used interchangeably during the 1980s, HIV—the human immunodeficiency virus—was the cause of AIDS, the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Shilts explores the early populations most at risk for this mysterious disease. The largest of these groups was homosexual men. The second group was hemophiliacs, people—many of them children—who needed frequent blood transfusions in order to compensate for their genetic disorder that prevented their blood from clotting. The third group was intravenous drug users.

Gay men, sick children, and intravenous drug users had at least one thing in common in the early to mid-1980s: none of these groups had much political influence. And as a result of this lack of voice and the political indifference of the American government, HIV became a national and worldwide pandemic. As journalist Igor Volsky reported:

Reagan’s surgeon general…explained that “intradepartmental politics” kept Reagan out of all AIDS discussions for the first five years of the administration “because transmission of AIDS was understood to be primarily in the homosexual population and in those who abused intravenous drugs.” The president’s advisers, Koop said, “took the stand, ‘They are only getting what they justly deserve.'”Igor Volsky, “Recalling Ronald Reagan’s LGBT Legacy Ahead Of The GOP Presidential Debate ”

Think Progress (September 7, 2011)

This pandemic and the indifference that allowed it to fester and spread is the theme of Teraoka’s work. The artist had a friend whose child was infected with HIV when given a tainted blood product. In American Kabuki, we see a mother—either rising from the waves or being torn down by them, we cannot tell—who clutches her child under her left arm. Her wind-tousled hair and terrified eyes provide a sense of horror to the scene, as do the skeletal, finger-like shape of the waves.

Within the framework of Japanese history, blackened teeth suggested the married status of a woman, but in Teraoka’s image it also serves to suggest eminent death and decay. The lesions on her cheek, forehead and forearm likely suggest Kaposi’s sarcoma, purple blotches on the skin that was one of the earliest symptoms of AIDS. The green hue around her eyes (and around the head of her largely hidden child) was frequently used in Kabuki theater performances to suggest a ghost or spirit. This, when combined with her teeth and lesions all suggest what people had come to know in 1986 even if they had not yet developed the vocabulary to express it: once a person had HIV they would in time have AIDS, and once they had AIDS they would soon die.

In time, the HIV/AIDS pandemic would become a plague on all of our houses, a tidal wave of death that has not yet been cured. Teraoka eloquently speaks to that destruction and the indifference of the government to advocate on behalf of those in need.

Understanding art to understand American culture

Art is, of course, the product of a unique moment in time, and it can take many forms. It can be a piece of furniture carved from wood; it can be a large-scale folded screen meant to mimic works made centuries ago in a far-off land an ocean away. While art many not speak in absolute truths, a careful and thoughtful analysis of it can provide crucial information about the shifts of American society and how it has changed and evolved over the centuries. What America is now is not what it has always been, and what it is now is not what it will become in the future. But regardless of when or where, artists will create art to chronicle the happenings of their time and provide future generations with insight into to their own culture and society.